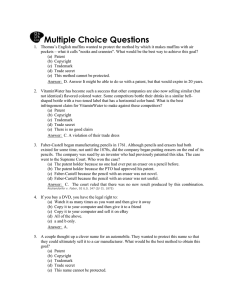

Fall 2009 - UW Law Student Bar Association

advertisement