Language - ameipc - home

advertisement

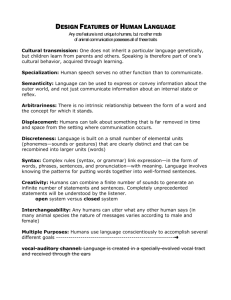

Memory and Cognition PSY 324 Topic: Language Dr. Ellen Campana Arizona State University What is language? “a system of communication using sounds or symbols that enables us to express our feelings, thoughts, ideas, and experiences” Human (animals have simpler systems) Bees signal through “waggle dance” Chimps have simple calls Snakes Eagles Leopards Essential Properties of Language Semanticity Arbitrariness Flexibility of Symbols Naming Displacement Productivity Productivity of Language (“Creativity” in the text) Language is hierarchical Made up of different parts that can be combined Parts form a hierarchy Larger and larger units Hierarchical Structure S NP Det VP N the mouse V saw NP Det N the cat Productivity of Language (“Creativity” in the text) Language is hierarchical Made up of different parts that can be combined Parts form a hierarchy Larger and larger units Language is governed by rules Some things are permissible and others are not OK: What is my cat saying? NOT OK: Cat my saying is what? Universality of Language Everyone with normal capacities develops a language and learns its complex rules implicitly Not talking about prescriptive grammar, but knowledge that produces permissible language Language occurs in all cultures Over 5000 different languages No culture without a language Even isolated communities have language Universality of Language Urge to communicate is powerful Children who are deaf but not exposed to sign develop their own languages (homesign) Language development consistent across cultures Babbling @ 7 months First words @ 1 year Multiword utterances @ 2 years All languages are “unique but the same” Unique but the same Languages are unique Different sounds, words, rules All different, but sometimes similar Languages are the same Have words that serve as nouns / verbs Have a system to make things negative (e.g. “not”) Have a way to ask questions Have a way to refer to past and present Have a way to refer to things that are not present Study of Language Wundt wrote about language in 1900 but detailed study started with cognitive revolution Skinner: Verbal Behavior People are trained to speak through conditioning Noam Chomsky Syntactic Structures described similarities and differences across languages (Zellig Harris work) Humans are genetically programmed for language Critique of Verbal Behavior introduced the poverty of the stimulus argument, which shattered behaviorism Poverty of the Stimulus Behaviorist argument: children learn on the basis of feedback from parents Child says “cat eat” Parent corrects with “the cat will eat” Poverty of the stimulus argument Children do not get enough feedback to learn Language requires production of things never heard before Classic example: “I hate you, Mommy.” Study of Language Disciplines that investigate language Linguistics: like philosophy + anthropology Natural Language Processing: computer science / AI Psycholinguistics: cognitive psychology Psycholinguistic study of language Comprehension – how we understand language Production – how we produce language Representation – how we represent or code language Acquisition – how we learn language Language Comprehension Levels of Language Pragmatic Level (use in the real world) Semantic Level (meaning) Syntactic Level (sentences) Lexical Level (words) Morphological Level (meaningful parts) Phonological Level (sounds) Understanding Words Comprehension of Words Lexicon: All of the words a person understands Often called a “Mental Dictionary” Adults have over 50,000 different words Contains meaning, grammatical category, phonemes, and rules about combining with morphemes Comprehension of Words Phonemes: The sounds of a language Shortest segment of speech that, if changed, alters the meaning of the word within a language Different languages have different sounds (and therefore different phonemes) Not quite the same as our letters, but close Number of phonemes varies by language Morphemes: in between words and sounds Smallest unit with a definable meaning OR grammatical function Examples: truck, -ed, -s, banana Perceiving Words Perception of (spoken) words is about how we link the sounds we hear to our lexicon As in the perception unit, it’s useful to think about top-down and bottom-up processes Top and bottom determined by levels of language Levels of Language Pragmatic Level (use in the real world) Semantic Level (meaning) Syntactic Level (sentences) Lexical Level (words) Morphological Level (meaningful parts) Phonological Level (sounds) Perceiving Words Perception of (spoken) words is about how we link the sounds we hear to our lexicon As in the perception unit, it’s useful to think about top-down and bottom-up processes Top and bottom determined by levels of language In the book “context” is usually top HUGE topic, will only be able to give you a bit of an overview Perception of Words Meaning of a word create a context that helps us actually hear the sounds of the word Top-down effect on phoneme perception Phonemic Restoration Effect (Warren, 1970) Researchers edited coughs into sentences (actually replacing phonemes with the cough, not mixing) Participants heard sentences, had to say what they heard and where the cough occurred Warren (1970) Sentence: The state governors met with their respective legislatures convening in the capital city. Results: People couldn’t report where the cough was People didn’t know the /s/ was missing Explanation: People seemed to “fill in” missing info based on context provided by sentence (and lexicon) Warren (1970) Sentence: It was time to ave goodbye to the family. Results: People couldn’t report where the cough was People didn’t know the /w/ was missing Explanation: People seemed to “fill in” missing info based on context provided by sentence (and lexicon) Warren (1970) Sentence: It was time to ave up for a new roof. Results: People couldn’t report where the cough was People didn’t know the /s/ was missing Explanation: People seemed to “fill in” missing info based on context provided by sentence (and lexicon) Phonemic Restoration Effect People use context to “fill in” missing or degraded sound information Can be context before or after the sound itself Very quick, people aren’t aware It is a demonstration of a top-down effect (context effect) on word perception Speech Segmentation Ever notice how… Language you don’t know – words blend together Your language – words seem separate You are using your knowledge of the language to find the word boundaries Meaning and Segmentation Same signal segments differently in different sentences Be a big girl and eat your vegetables The thing Big Earl loved most was his truck Fun demo: Mad Gab game. For this you need to find a friend to help you. Mad Gab Instructions Take turns with the following roles: Person A: Close your eyes, listen, and try to figure out what the other person is saying Person B: Read the slide out loud (you may have to repeat a few times). Talk about it – Person A will hear something different than what Person B was saying “Mad Gab” demo Ask Rude Arrive Her “Mad Gab” demo Eight Ape Reek Quarter “Mad Gab” demo Amen Ask Hurt “Mad Gab” demo Eye Mull Of Mush Sheen “Mad Gab” demo I’ve Hailed Ink Lush Mad Gab What was the point of doing this for class? Meaning affects which phonemes you hear and where the word boundaries are (top-down) This meaning comes from your previous experience with Language Based on actual sentences or phrases in English, rather than just words There are also bottom-up aspects of speech segmentation Transitional Probabilities and Segmentation Transitional probabilities: the chances that one sound will follow another sound Sounds “pretty” more likely than “tyba” in English When we hear “prettybaby” we segment it into the words “pretty” and “baby” We can learn to do this even if the words are not meaningful, through statistical learning Tested with 8-month-olds (Saffran&colleagues, 1996) Still knowledge, just knowledge of the language Statistical Learning Study with 8-month-olds Training: infants heard a stream of nonsense “words” for two minutes …bidakupadotigolibutupiropadotibidaku… No pauses, random order, flat intonation Testing: infants chose how long to listen to test stimuli by turning their heads Whole word: padoti…padoti…padoti Part word: libutu…libutu…libutu Infants could tell which one (preferred part) Perceiving Letters So far we’ve been talking about understanding the sounds in spoken language. Top-down and bottom-up effects Understanding written letters is similar Visual perception of the letters themselves is both top-down and bottom-up (from chapter 3) Word superiority effect shows that words affect processing of letters (top-down) Perception of Letters Word Superiority Effect Coglab / Example in the book…. Stimuli: word (FORK), nonword (RFOK), or letter (K), followed by a target & distractor Task: choose the target Finding: People are more accurate and faster at picking the target when the stimulus is a word, compared to when it is *alone* or part of a nonword Word Superiority Effect What’s the point of this study? Demonstrates that the top-down context (the word) helps with processing There’s a model of this that my help you visualize this. Picture “spreading activation” going from bottom to top and then back down Only some features are shown – the model would be complete If this doesn’t help, it’s OK! (not on exam) Interactive Activation Model Word Level Letter Level ROOF FORK F K Feature Level Stimulus K O R Understanding Words Word Frequency Effect We respond more quickly to high frequency words (home vs. hike). Supported with lexical decision studies Task = word or nonword Findings = faster to say a high-frequency word is a word than to say a low-frequency word is a word Supported by faster reading times Eye movements Overall reading times (story with pretty vs. demure) Lexical Ambiguity Same word has different meanings “Bugs” = insects OR recording devices “Bank” = river bank OR financial institution When reading, both meanings are accessed right away, but then context overrides one of them Shown with lexical priming at “bug” in a story Simultaneous presentation: “spy” / “ant” equally fast 200 ms delay: context-specific meaning faster Understanding Sentences Levels of Language Pragmatic Level (use in the real world) Semantic Level (meaning) Syntactic Level (sentences) Lexical Level (words) Morphological Level (meaningful parts) Phonological Level (sounds) Syntax vs. Semantics Meaning / Semantics Semantic violation: “The cats won’t bake.” It’s English but it doesn’t seem meaningful Form / Syntax Syntactic violation: “Cat bird the chased.” You can guess what it might mean, but it doesn’t follow the rules of English Recall discussion from Chapter 2 – different brain areas for these two levels of language Parsing Most of the time language is successful No syntactic or semantic violations Syntax and semantics work together Meaning of whole sentence depends on syntax How words are grouped together, or parsed, can have a major effect Example: Ambiguous sentences Example: Garden Path sentences Ambiguous Sentences Ambiguous means that it has more than one interpretation We saw ambiguous man-rat pictures in the perception chapter Some sentence ambiguities depend on structure Example: “I saw the spy with the telescope” Option 1: Phrase “with the telescope” is grouped with “spy” Option 2: Phrase “with the telescope” is grouped with “saw” Ambiguity SPEAKER ACME TELESCOPE JOHN “I saw the spy with the telescope.” Ambiguity SPEAKER ACME TELESCOPE JOHN “I saw the spy with the telescope.” Ambiguity SPEAKER ACME TELESCOPE JOHN “I saw the spy with the telescope.” Temporary Ambiguity In the spy example we never really know which parse is the right one (it remains ambiguous) but for others the structure becomes clear over time Time flies like an arrow. Fruit flies like a banana. Garden Path Sentences We process language as it unfolds (sound by sound, word by word) Part of this involves parsing (grouping words) Sometimes we have to revise these groupings as we get new information Feels very confusing! Garden Path Sentences Read this and pay attention to how confusing it feels: The man who whistles tunes pianos. You were likely confused when you got the word “pianos” First parse: “tunes” grouped with “whistles” Revised parse: “tunes” grouped with “pianos” Approaches to Parsing Syntax-first Approaches – parsing is based on syntax and later compared with semantics Late Closure Minimal Attachment (not in our book) Attach to current constituent if possible Group words in the simplest way Interactionist Approaches – parsing is based on interactions between syntax and semantics Meaning affects parse from the earliest moments We never ever think of this one! (as in: I saw wood with the bandsaw) SPEAKER ACME TELESCOPE JOHN “I saw the man with the telescope.” Evidence for Interactionist Approach to Parsing Lexical Semantics Man with binoculars vs bird with binoculars Meaning of the first word (man/bird) affects parses Pragmatics / Environment Tanenhaus et al studies Head-Mounted Eye Tracker • Like looking into someone’s thoughts • As they happen, in a real environment! 600.465 - Intro to NLP - J. Eisner 59 slide courtesy of M. Tanenhaus (modified) Videotape • From Mike Tanenhaus’s lab – University of Rochester Eye camera Scene camera 600.465 - Intro to NLP - J. Eisner 60 slide courtesy of M. Tanenhaus (modified) PP Attachment Ambiguity Put the apple on the towel in the box. Only one apple Garden Path Put the apple on the towel in the box. Two apples use PP to clarify which apple, no garden path 600.465 - Intro to NLP - J. Eisner 61 slide courtesy of M. Tanenhaus One referent context garden path oops! backtrack slide courtesy of M. Tanenhaus One referent context slide courtesy of M. Tanenhaus Two-referent context amazing lack of oops Tanenhaus Study What???? If there are two apples, people don’t get confused because “on the towel” is needed to distinguish between the two apples -- this means that only one possible parse makes sense If there is only one apple, people are confused because both parses are OK, but the one that groups “on the towel” with “put” is more natural. Garden path effect Understanding Text and Stories Constructive Nature of Language In previous chapters we’ve discussed cases where we construct aspects of experience Top-down aspects of vision Gestalt processes Scripts / Schemas Memory Eyewitness Testimony Language understanding is constructive too! Construction = “inference” Inferences Anaphoric inference What do “he” / “she” / “it” / “they” mean in context? Which cat is “the orange cat” or “my favorite cat”? Instrument inference Was an instrument used to perform an action? Use our scripts to make these inferences Causal inference Are sentences linked by causal relationships? Situation Models We imagine the details of situations we read about using our knowledge of the world Scripts, schemas, inference Visual imagery, spatial relationships Simulations (like imagery but including other sense, and actions) Studies demonstrating these Eagles and nails Vampire TV show Physiology of Situation Models When reading Areas of the brain related to performing an action are active when reading about the action Areas of the brain involved in sensing (visual, auditory, smell, etc.) are active when reading about sensed environments Distributed Activity Reading involves the whole brain Changes of different types associated with different areas Producing Language Conversations Language Production in General How do people understand each other in conversations? Conversations involve simultaneous language comprehension and production Each of these is an incredibly complex topic, so the book can only give a little taste of the area Coordination – staying “on the same page” Semantic Coordination Syntactic Coordination Semantic Coordination Recall that language is constructive Anaphoric inferences allow us to link referring expressions (i/we/ they / the beer) to objects in the real world Speakers and listeners need to coordinate to make sure they are always making the same inferences Example: Given / New contract Definite noun phrases (“the x”) refer to previously introduced objects Followed by both speakers and listeners Syntactic Coordination Ambiguity can make it harder to communicate quickly (e.g. garden path sentences) Speakers and listeners coordinate syntax to reduce ambiguity Example: Syntactic priming… I say “Sue gave the boy the ball” you say “Sally gave the girl the bat” (same syntax) not “Sally gave the bat to the girl” Often syntactic coordination (including priming) happens automatically and unconsciously Culture, Language and Cognition The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Basic idea: The language people use affects the way they perceive the world around them Example: color terms in a language determine how well we can discriminate (i.e. tell the difference between) different colors Also: Objects, numbers, space, mathematical concepts Left vs right brains process concepts differently (left more likely to show Sapir-Whorf patterns THE END This chapter just scratches the surface of the exciting world of language, but I may be biased because that’s what I do….. If you are interested in language as a topic and would like to become involved in this kind of research, get in touch with me PGS 399 credit PGS 499 credit Honors thesis credit