Machiavelli - New Jersey City University

advertisement

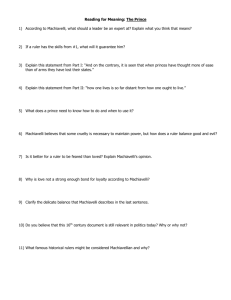

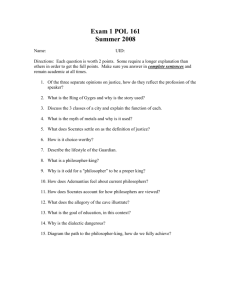

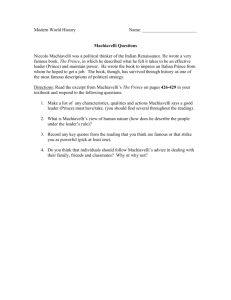

Machiavelli The Prince Machiavelli’s The Prince Historical Overview Human Nature and Power Fortune & Virtue Forms of Government I. Historical Overview Niccolò Machiavelli (1469 – 1527) European Renaissance Declining power of Church Advancing in Science, Arts, Literature The Prince written in 1513 during period of political exile Copernican Universe I. Historical Overview Machiavelli & Florence Medici family rules city French forces invade, set up republican government Machiavelli gets role in government, ends up as high civil servant, some diplomatic missions and military operations I. Historical Overview Machiavelli & Florence Spanish defeat the French, and reinstall the Medici Machiavelli is arrested, tortured, and eventually exiled to his country home beyond the city walls During this period (he’s in his 40s) he begins his philosophical/political writing, including The Prince I. Historical Overview Machiavelli & Florence Prince is dedicated to Lorenzo de Medici, the Magnificent But this Medici is the grandson of the founder of the Medici dynasty, Lorenzo il Magnifico, the genuine Lorenzo the Magnificent Machiavelli & Florence The Prince as extended job application? Two aims: 1. 2. Secure a government job Provide recipe for stabilizing Italian city states to protect them from outside interference, whether civil or ecclesiastical II. Human Nature and Power “The desire to acquire is truly a very natural and common thing; and whenever men who can, do so, they are praised and not condemned; but when they cannot and want to do so just the same, herein lies the mistake and the condemnation.” (Chapter 3). II. Human Nature and Power Contrast with Greeks/Aquinas Implications? Human beings are selfish animals Need to construct a political life which is based on how people actually behave, not how we want them to be But… II. Human Nature and Power Doesn’t want to reject either rational politics (the Greeks) or religious salvation (the church) out of hand Rather, the goals of these two projects must come not from directives by external sources but through personal choices II. Human Nature and Power These personal choices will only come about if and when we appreciate the factors that motivate people in making their choices Each individual is fully responsible for his/her choices Each of us share this responsibility since we each share the same human nature II. Human Nature and Power Power Machiavelli the first political thinker to focus on power as positive trait Simple recognition of the fact that the quest for power is an essential part of human nature Why? II. Human Nature and Power If we want to acquire possessions, then that implies that we also want the means to acquire those possessions Need to recognize that for rulers the study of power is vital: how to acquire it, how to keep it, how to use it II. Human Nature and Power “Many writers have imagined for themselves republics and principalities that have never been seen nor known to exist in reality; for there is such a gap between how one lives and how one ought to live that anyone who abandons what is done for what ought to be done learns his ruin rather than his preservation…” (chapter 15) II. Human Nature and Power “for a man who wishes to profess goodness at all times will come to ruin among so many who are not good” (chapter 15). II. Human Nature and Power Indeed, Machiavelli asserts: “For one can generally say this about men: they are ungrateful, fickle, simulators and deceivers, avoiders of danger, greedy for gain; and while you work for their good they are completely yours, offering you their blood, their property, their lives, and their sons, as I said earlier, when danger is far away; but when it comes nearer to you they turn away” (chapter XVII). II. Human Nature and Power So if a Prince or ruler wants to stay in power, he must “Learn how not to be good, and to use this knowledge or not to use it according to necessity” (chapter XV) II. Human Nature and Power What does this mean? Machiavelli is not advising us to behave badly simply for the sake of being evil II. Human Nature and Power Rather since we see power in political life we need to counsel rulers on how best to use it Basic advice, don’t help others, be cruel, stingy, deceptive… And get others to do the dirty work so you can escape blame II. Human Nature and Power “You must, therefore, know that there are two means of fighting: one according to the laws, the other with force; the first way is proper to man, the second to beasts; but because the first, in many cases is not sufficient, it becomes necessary to have recourse to the second” (chapter XVIII). II. Human Nature and Power “Since, then, a prince must know how to make good use of the nature of the beast, he should choose from among the beasts the fox and the lion; for the lion cannot defend itself from traps and the fox cannot protect itself from wolves. It is therefore necessary to be a fox in order to recognize the traps and a lion in order to frighten the wolves.” II. Human Nature and Power Examples? Chapter VII • “Cesare Borgia acquired the state through the favour and help of his father, and when this no longer existed, he lost it, and this despite the fact that he did everything and used every means that a prudent and skilful man ought to use in order to root himself securely in those states that the arms and fortune of others had granted him” II. Human Nature and Power Background here: Cesare’s father? Pope Alexander VI The Pope put Cesare in charge of Florence, and issued a formal papal bull (order) authorizing him to expand the power of Florence What were some of the means used by this “prudent” and “skilful” man? II. Human Nature and Power Later in the chapter we get one example Borgia takes over Romagna, but is meeting resistance since “it was ruled by powerless noblemen who had been quicker to despoil their subjects than to govern them, and gave them cause to disunite rather than to unite them” II. Human Nature and Power He decided it was necessary to bring “peace and obedience of the law” and installed a man named Remirro de Orca, a “cruel and efficient man” to rule Then, after the area was pacified, Borgia does the following: II. Human Nature and Power “Since he knew that the severities of the past had brought about a certain amount of hate, in order to purge the minds of those people and win them over completely, he planned to demonstrate that if cruelty of any kind had come about, it did not stem from him [Borgia] but rather from the bitter nature of the minister…” II. Human Nature and Power “And having found the occasion to do this, he had him placed one morning in Cesena on the piazza in two pieces with a piece of wood and a bloodstained knife alongside him.” II. Human Nature and Power “The atrocity of such a spectacle left those people at one and the same time satisfied and stupefied.” II. Human Nature and Power Story of Agathocles the Sicilian (chapter VIII) Story of Oliverotto of Fermo (chapter VII) Footnote: A year after the events described here (1512), Cesare had Fermo strangled and the corpse displayed on the main square of Senigallia for 3 days II. Human Nature and Power Conclusion? “In taking a state its conqueror should weigh all the harmful things he must do and do them all at once so as not to have to repeat them every day, and in not repeating them to be able to make men feel secure and win them over with the benefits he bestows upon them” II. Human Nature and Power Machiavelli is not counseling the need to be cruel, nor denying that cruelty is sometimes useful, but rather showing how to limit its worst effects The primary requirement for selfish individuals seeking personal goals is to enter into reciprocal relationships where each needs power or influence over the behavior of others II. Human Nature and Power In entering these relationships, all are equal in their selfishness, and all are free to seek power He’s not saying that people will never act on the common good, only that they will do so only if they see an identity between their private interest and the common good II. Human Nature and Power Those who appear good or altruistic to others are either rational actors really motivated by desire for personal advantage, or ruled by laziness and retreating from their political responsibilities II. Human Nature and Power “And it is essential to understand this: that a prince, and especially a new prince, cannot observe all those things for which men are considered good, for in order to maintain the state he is often obliged to act against his promise, against charity, against humanity, and against religion…” II. Human Nature and Power “And therefore, it is necessary that he have a mind ready to turn itself according to the way the winds of fortune and the changeability of affairs require him; and, as I said above, as long as it is possible, he should not stray from the good, but he should know how to enter into evil when necessity commands” (Chapter XVIII). III. Fortune and Virtue But what happens if you follow Machiavelli’s principles? Is success guaranteed Recall the passage about Cesare Borgia, the model for much of Machiavelli’s discussion: III. Fortune and Virtue “Cesare Borgia acquired the state through the favour and help of his father, and when this no longer existed, he lost it, and this despite the fact that he did everything and used every means that a prudent and skilful man ought to use in order to root himself securely in those states that the arms and fortune of others had granted him” (emphasis added) III. Fortune and Virtue Machiavelli recognizes that sometimes, despite the best planning, education, and skill, events still turn out badly That is, fortune or luck is also a part of our political life III. Fortune and Virtue Chapter XXV “I judge it to be true that fortune is the arbiter of one half of our actions, but that she still leaves the control of the other half, or almost that, to us.” Flooding river analogy III. Fortune and Virtue What to do? 1. 2. Follow Machiavelli’s prescriptions. That is, learn the virtues of ruling “I also believe that the man who adapts his course of action to the nature of the times will succeed and, likewise, that the man who sets his course of action out of tune with the times will come to grief” (XVIII). III. Fortune and Virtue In other words, a good ruler is one who can adapt to changing circumstances It means knowing when to be cautious and hesitant, or bold and forceful, as the occasion demands. III. Fortune and Virtue Knowing what to do and when to do it is part of Machiavelli’s understanding of virtue Unlike the ancient philosophers or Christian theologians, virtue is divorced from the idea of a code of conduct, of “good” versus “bad” ways of acting III. Fortune and Virtue Instead, for Machiavelli, virtue is individualistic [contra the Greeks and Romans] and secular [contra the Church] Not some idealistic merit or moral goodness, but … III. Fortune and Virtue A true selfishness that enables individuals to get what they value, whether power, wealth, fame, etc. Those who get what they seek have demonstrated their virtue and they are judged, in Machiavelli’s criteria, as good. By adapting – by adjusting cunning and strength, by following the fox and the lion – a virtuous ruler is one who can see trouble on the horizon (the work of fortune) and act rather than be taken off-guard by changing events III. Fortune and Virtue Because a political state is passive (events happen to it), it needs constant attention devoted to creating order and avoiding disorder IV. Forms of Government What is the best way to maintain the state? What is the best form of government? What are the basic forms of government? IV. Forms of Government Unlike Aristotle, Machiavelli argues that basically we have two forms: 1. Republic 2. Monarchy “All the states, all the dominions that have had and still have power over men, were and still are either republics or principalities” (first sentence, Chapter 1) IV. Forms of Government But throughout The Prince, that distinction blurs a bit, with monarchies or “civic principalities” ending up looking very similar to republics The real distinction is then between republics and tyrannies (i.e., those monarchies or principalities which differ from republics). IV. Forms of Government Republics: Founded by a strong, inspirational leader rallying the citizenry Based on law Governed in the interest of the majority, not of a special elite Mixed class – members of all classes have opportunity to participate IV. Forms of Government Note, republics require a special citizenry: active, engaged, public spirited Unlikely to have those conditions in every area, so tyranny is inevitable IV. Forms of Government Tyrannies Masses are subjects, not active participants in political life Ruling classes enjoy more liberty, and when interests of rulers conflict with liberty of the masses, the rulers prevail IV. Forms of Government The masses are content with this arrangement since they recognize that without the ruler, anarchy would ensue, or They’re content because they are either fearful or awestruck of the powers that be IV. Forms of Government Lacking the virtue of citizens in a republic, the masses under tyrannical regimes both merit and need tyranny And when a tyrant is stuck governing a bunch of corrupt, vulgar masses who lack virtue, then ordinary morality is not binding and he/she/they can pretty much do what they must to stay in power