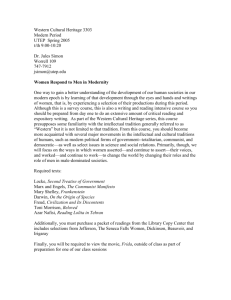

Reading Lolita in Tehran Introduction and Discussion Questions

advertisement

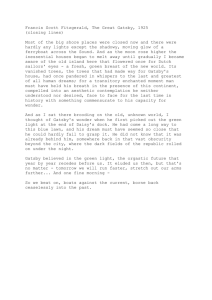

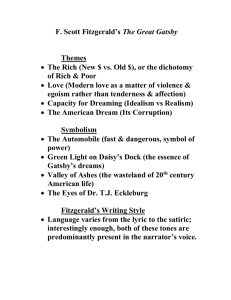

Reading Lolita in Tehran Introduction Discussion Questions About the author Dr. Azar Nafisi Iranian-American Lived in Iran until she was 13 Moved to England to go to school Went back to Iran in 1979 after she finished college Lived there for 18 years (part of the setting of the novel) About the author Struggled with “home” What is “home”? Where you were born? Where they practice your cherished values? Discussion Questions “Lolita” Section (pp. 1-78) 1. Yassi adores playing with words, particularly with Nabokov's fanciful linguistic creation upsilamba. What does the word upsilamba mean to you? (Lolita Section, p. 18-21) “Lolita” Section (pp. 1-78) 2. In discussing the frame story of A Thousand and One Nights, Dr. Nafisi mentions three types of women who fell victim to the king's "unreasonable rule." How relevant are the actions and decisions of these fictional women to the lives of the women in Dr. Nafisi's private class? (Lolita Section, p. 19) “Lolita” Section (pp. 1-78) 3. Discuss the recurrent theme of complicity in the book: that the Ayatollah, the stern philosopher-king, "did to us what we allowed him to do." (Lolita Section, p. 28) “Lolita” Section (pp. 1-78) 4. The confiscation of one's life by another is the root of Humbert's sin against Lolita. How did Khomeini become Iran's solipsizer? Discuss how Sanaz, Nassrin, Azin and the rest of the girls are part of a generation with no past.” (Lolita Section, p. 76) “Lolita” Section For Tonight… Dr. Nafisi describes Humbert, the “poet/villain” of Lolita in the following way: “ Like the best defense attorneys, who dazzle with their rhetoric and appeal to our higher sense of morality, Humbert exonerates himself by implicating his victim—…” (42) Reread chapter 13 in the “Lolita” section. Compare the ideology and methodology of Humbert and one other character from a work we have read this year. “Gatsby” Section (pp. 79-154) 1. On her first day teaching at the University of Tehran, Dr. Nafisi began class with the questions, "What should fiction accomplish? Why should anyone read at all?" What are your own answers? How does fiction force us to question what we often take for granted? (Gatsby Section, p. 94). “Gatsby” Section (pp. 79-154) 2. Dr. Nafisi teaches that the novel is a sensual experience of another world which appeals to the reader's capacity for compassion. Do you agree that "empathy is at the heart of the novel"? How has this book affected your understanding of the impact of the novel? (Gatsby Section, p. 111) “Gatsby” Section (pp. 79-154) 3. During the Gatsby trial Zarrin charges Mr. Nyazi with the inability to "distinguish fiction from reality." How does Mr. Nyazi's conflation of the fictional and the real relate to theme of the blind censor? Describe similar instances within a democracy like the United States when art was censored for its "dangerous" impact upon society. (Gatsby Section, p. 128) “Gatsby” Section (pp. 79-154) 4. Dr. Nafisi writes: "It was not until I had reached home that I realized the true meaning of exile." How do her conceptions of home conflict with those of her husband, Bijan, who is reluctant to leave Tehran? Also, compare Mahshid's feeling that she "owes" something to Tehran and belongs there to Mitra and Nassrin's desires for freedom and escape. Discuss how the changing and often discordant influences of memory, family, safety, freedom, opportunity and duty define our sense of home and belonging. (Gatsby Section, p. 145) “Gatsby” Section For Tonight… “I explained that most great works of the imagination were meant to make you feel like a stranger in your own home. The best fiction always forced us to question what we took for granted. It questioned traditions and expectations when they seemed too immutable.” (94) Explain Dr. Nafisi’s statement. Why should fiction make us feel, at times, uncomfortable? What does an author gain by subverting the very traditions of his readers? “James” Section (pp. 155-254) 1. Explain what Dr. Nafisi means when she says people, “like myself had become irrelevant.” Compare her way of dealing with her irrelevance to her magician's self-imposed exile. (James Section, pp. 167-176) “James” Section (pp. 155-254) 2. Compare attitudes toward the veil held by men, women and the government in the Islamic Republic of Iran. How was Dr. Nafisi's grandmother's choice to wear the chador marred by the political significance it had gained? Also, describe Mahshid's conflicted feelings as a Muslim who already observed the veil but who nevertheless objected to its political enforcement. (James Section, p. 192) “James” Section (pp. 155-254) 3. Fanatics like Mr. Ghomi, Mr. Nyazi and Mr. Bahri consistently surprised Dr. Nafisi by displaying absolute hatred for Western literature — a reaction she describes as a "venom uncalled for in relation to works of fiction." What are their motivations? Do you, like Dr. Nafisi, think that people like Mr. Ghomi attack because they are afraid of what they don't understand? Why is ambiguity such a dangerous weapon to them? (James Section, p. 195) “James” Section (pp. 155-254) 4. In what ways had Ayatollah Khomeini "turned himself into a myth" for the people of Iran? (James Section, p. 246) “Austen” Section (pp. 255-340) 1. “Personal and political are interdependent but not one and the same. The realm of imagination is a bridge between them, constantly refashioning one in terms of the other. … it was perhaps not surprising that the Islamic Republic’s first task had been to blur the lines and boundaries between the personal and political thereby destroying both.” (Austen Section, p. 273) Why does Dr. Nafisi believe that what is personal must be separate from what is political? What protections from our government do we have expressly written in the Constitution to keep these lines from blurring? How does the combination of the “personal” and “political” destroy both the public and private arenas of a person’s life?