Lecture 4 - Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering

advertisement

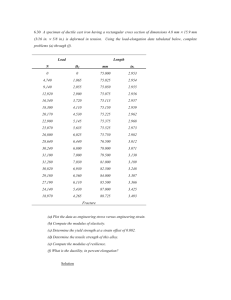

Mechanics of Materials – MAE 243 (Section 002) Spring 2008 Dr. Konstantinos A. Sierros Problem 1.2-11 A reinforced concrete slab 8.0 ft square and 9.0 in. thick is lifted by four cables attached to the corners, as shown in the figure. The cables are attached to a hook at a point 5.0 ft above the top of the slab. Each cable has an effective cross-sectional area A = 0.12 in2 . Determine the tensile stress σt in the cables due to the weight of the concrete slab. (See Table H-1, Appendix H, for the weight density of reinforced concrete.) Problem 1.3-3 Three different materials, designated A, B,and C, are tested in tension using test specimens having diameters of 0.505 in. and gage lengths of 2.0 in. (see figure). At failure, the distances between the gage marks are found to be 2.13, 2.48, and 2.78 in., respectively. Also, at the failure cross sections the diameters are found to be0.484, 0.398, and 0.253 in., respectively. Determine the percent elongation and percent reduction in area of each specimen, and then, using your own judgment, classify each material as brittle or ductile. Problem 1.3-6 A specimen of a methacrylate plastic is tested in tension at room temperature (see figure), producing the stress-strain data listed in the accompanying table. Plot the stress-strain curve and determine the proportional limit, modulus of elasticity (i.e., the slope of the initial part of the stress-strain curve), and yield stress at 0.2% offset. Is the material ductile or brittle? Solution to Problem 1.3-6 70 60 proportional limit Stress, MPa 50 yield stress 40 Modulus of elasticity = 2.35 GPa 30 Proportional limit = 47 MPa 20 Yield stress = 52.5 10 0 0.00 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.05 Strain Material is brittle, because the strain after the proportional limit is exceeded is relatively small. 1.4: Elasticity • What happens when the load is removed (i.e. the material is unloaded)? • Tensile load is applied from O to A (fig 1.18a) and when load is removed the material follows the same curve back. This property is called elasticity • If we load the same material from O to B (fig 1.18b) and then unloading occurs, the material follows the line BC. Line OC represents the residual or permanent strain. Line CD represents the elastic recovery of the material. During unloading the material is partially elastic Stress-strain diagrams illustrating (a) elastic behavior, and (b) partially elastic behavior FIG. 1-18 Copyright 2005 by Nelson, a division of Thomson Canada Limited 1.4: Plasticity “ Plasticity is the characteristic of a material which undergoes inelastic strains beyond the strain at the elastic limit ” When large deformations occur in a ductile material loaded in the plastic region, the material is undergoing plastic flow 1.4: Reloading of a material • If the material is in the elastic range, it can be loaded, unloaded and loaded again without significantly changing the behaviour • When loaded in the plastic range, the internal structure of the material is altered and the properties change • If the material is reloaded (fig 1-19), CB is a linearly elastic region with the same slope as the slope of the tangent to the original loading curve at origin O • By stretching steel or aluminium into the plastic range, the properties of the material are changed Reloading of a material and raising of the elastic and proportional limits FIG. 1-19 Copyright 2005 by Nelson, a division of Thomson Canada Limited 1.4: Creep • When loaded for periods of time, some materials develop additional strains and are said to creep • Even though the load P remains constant after time t0, the bar gradually lengthens FIG. 1-20 Creep in a bar under constant load Copyright 2005 by Nelson, a division of Thomson Canada Limited FIG. 1-21 Relaxation of stress in a wire under constant strain • Relaxation is a process at which, after time t0 , the stress in the wire gradually diminishes and eventually is reaching a constant value • Creep is more important at high temperatures and has to be considered in the design of engines and furnaces Copyright 2005 by Nelson, a division of Thomson Canada Limited 1.5: Hooke’s law Many structural materials such as metals, wood, plastics and ceramics behave both elastically and linearly when first loaded and their stressstrain curve begin with a straight line passing through origin (line OA) Stress-strain diagram for a typical structural steel in tension (not to scale) FIG. 1-10 Copyright 2005 by Nelson, a division of Thomson Canada Limited Linear elastic materials are useful for designing structures and machines when permanent deformations, due to yielding, must be avoided 1.5: Hooke’s law The linear relationship between stress and strain for a bar in simple tension or compression is expressed by: σ is axial stress ε is axial strain E is modulus of elasticity σ=Eε Hooke’s law Robert Hooke (1635-1703) The above equation is a limited version of Hooke’s Law relating only the longitudinal stresses and strains that are developed during the uniaxial loading of a prismatic bar Robert Hooke was an English inventor, microscopist, physicist, surveyor, astronomer, biologist and artist, who played an important role in the scientific revolution, through both theoretical and experimental work. 1.5: Modulus of elasticity • E is called modulus of elasticity or Young’s modulus and is a constant • It is the slope of the stress – strain curve in the linearly elastic region • Units of E are the same as the units of stress (i.e. psi for USCS and Pa for SI units) • For stiff materials E is large (i.e. structural metals). Esteel = 190 - 210 GPa • Plastics have lower E values than metals. Epolyethylene = 0.7 – 1.4 GPa • Appendix H, Table H-2 contains values of E for materials Thomas Young was an English polymath, contributing to the scientific understanding of vision, light, solid mechanics, energy, physiology, and Egyptology. 1.5: Poisson’s ratio • When a prismatic bar is loaded in tension the axial elongation is accompanied by lateral contraction longitudinal extension lateral contraction • The lateral strain ε’ at any point in a bar is proportional to the axial strain ε at the same point if the material is linearly elastic Axial elongation and lateral contraction of a prismatic bar in tension: (a) bar before loading, and (b) bar after loading. (The deformations of the bar are highly exaggerated.) FIG. 1-22 Copyright 2005 by Nelson, a division of Thomson Canada Limited • The ratio of the above two strains is known as Poisson’s ratio (ν) ν = - (lateral strain / axial strain = - (ε’ / ε ) 1.5: Poisson’s ratio • The minus sign in the equation is because the lateral strain is negative (width of the bar decreases) and the axial tensile strain is positive. Therefore, the Poisson’s ratio will have a positive value. • When using the Poisson’s ratio equation we need to know that it applies only to a prismatic bar in uniaxial stress Simeon Denis Poisson (1781-1840) • Poisson’s value of concrete = 0.1 – 0.2 • Poisson’s value of rubber = 0.5 • Appendix H, Table H-2 contains values of ν for various materials Siméon-Denis Poisson was a French mathematician, geometer, and physicist. 1.5: Limitations • Poisson’s ratio is constant in the linearly elastic range • Material must be homogeneous (same composition at every point) • Materials having the same properties in all directions are called isotropic • If the properties differ in various directions the materials called anisotropic Axial elongation and lateral contraction of a prismatic bar in tension: (a) bar before loading, and (b) bar after loading. (The deformations of the bar are highly exaggerated.) FIG. 1-22 Copyright 2005 by Nelson, a division of Thomson Canada Limited Good luck with your homework Deadline: 28 January 2008