Threshold in APEC De Minimis 2012 English

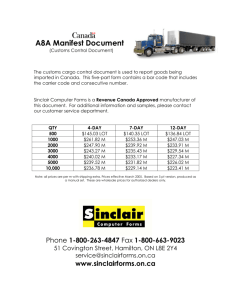

advertisement