How do cases get to the Supreme Court?

advertisement

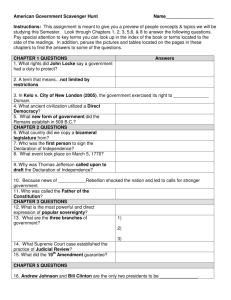

Procedure and Opinion Making in the Supreme Court GOVT 2305 This is a brief section designed to provide an overview of the process that cases take on their way to the Supreme Court. The goal here is for you take have some familiarity with how cases make their ways to the Supreme Court and what happens to them once they are there. Here are some documents that explain the process: US Courts: Supreme Court Procedures. ScotusBlog: Supreme Court Procedure. Wikpedia: Procedures of the Supreme Court. LII: Rules of the SCOTUS. Supreme Court Database Supreme Court Statistics If you are very ambitious you might want to chew on this: RULES OF THE Supreme Court of the United States As with bill making and rule making, the courts are responsible for making their own procedures. And these have changed over the course of time. We’ll look at these simple stages in the process – based on this description from ScotusBlog: Lower Courts Petition for Certiorari Merits Stages Oral Arguments Decision Lower Courts The process begins – always – with a case at the lower courts. (Well, this isn’t really true since the Supreme Court can hear some cases as a matter of original jurisdiction. These are very rare however. We wont worry about them here.) Cases can arise as a result of civil or criminal matters in a lower court. That court can be civil or criminal, state or federal. They can emerge from anywhere in the nation. Some recent major cases has come from the local area. Examples: Santa Fe Independent School Dist. v. Doe Atwater v. Lago Vista Santa Fe Independent School Dist. v. Doe The 2000 Supreme Court ruled that student-led, student-initiated prayer at high school football games violates the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. This amounts to an endorsement of one religious point of view by government – this case the independent school district. "Regardless of the listener's support for, or objection to, the message, an objective Santa Fe High School student will unquestionably perceive the inevitable pregame prayer as stamped with her school's seal of approval." The lawsuits was initiated by: “two sets of current or former students and their respective mothers—one Mormon, the other Catholic— objected to this practice and filed a suit on the basis of a violation of the Establishment Clause. Judge Samuel B. Kent of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas allowed the plaintiffs to remain anonymous to protect them from harassment. They are referred to as the Does. Interesting trivia: Samuel Kent would later resign from office on threat of impeachment and removal due a conviction for lying about sexually abusing female employees. Atwater v. Lago Vista This 2001 decision “held that a person's Fourth Amendment rights are not violated when the subject is arrested for driving without a seatbelt. The court ruled that such an arrest for a misdemeanor that is punishable only by a fine does not constitute an unreasonable seizure under the Fourth Amendment.” Cases can also emerge from the actions of either the legislative or executive branches. They can sue each other. If this occurs the lawsuits are filed with the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. As a reminder, here is the map of the federal courts. The cases that come from, and are decided in, each area can vary. The decisions made on the west coast – for example – can be different than the ones that emerge from the south. Part of what the court is supposed to do is reconcile these differences. If you look closely, you’ll see the doted lines which outline the trial courts. These are the courts of original jurisdiction where the civil or criminal case are heard. Federal cases from this area would start in the US District Court for the Southern District of Texas. Here’s the map: Here’s the website for the Southern District of Texas. Click here for notable cases from the court. Brazoria County is in the Galveston Division of the court. Cases that start in the state courts can also end up being appealed to the United States Supreme Court if it can be proved that state officials violated a federally guaranteed right. That’s what was argued in Atwater v. Lago Vista All cases have to begin with a decision in a trial court (civil or criminal) or a question from that court about the admissibility of evidence. It can also be either deliberately intended to challenge the constitutionality a law (a test case) or the product of a procedural question related to an issue that arises in the court. We discussed test cases previously. Often interest groups use these cases in order to change legislation – sometimes by asking the court to find it unconstitutional they are otherwise unable to. The Supreme Court can sometimes play a subtle role in doing so by “signaling” in some of its decisions that it is ready to make a certain decision. This can encourage groups – like the NAACP for example – that the court might be ready to overturn legal segregation, as it did in Brown v Board of Education. In that case, the NAACP recruited AfricanAmerican parents to attempt to enroll in racially segregated schools in Topeka, Kansas knowing that they would not be allowed in. That was the point. They sued based on a violation of the equal protection clause, the case made it to the Supreme Court and they won. Some cases arise because events on the ground – like an arrest – present novel issues that court has never considered before. Here’s a recent example: Riley v. California. The court ruled unanimously that “The police generally may not, without a warrant, search digital information on a cellphone seized from an individual who has been arrested.” This case began its journey to the Supreme Court when the San Diego police searched the cell phone of David Leon Riley after an arrest, without a warrant. Evidence of gang activity connected to a different crime was found and used against him. Police are generally able to conduct such searches after arrests, but the court ruled that cell phones are different due to the wealth of information it contains. Warrants are required in order to limit searches. This was not initiated as a test case, but it became one because it presented the court with an important question related to constitutional rights. This tells us something about what cases make it to the Supreme Court. Generally they are ones that present important constitutional questions to the court – questions that often arise because morays change (attitudes about race relations, the role of women in society, and the propriety of same sex relationships) and technology allows for searches to occur that previously could not. For more: Types of Cases the Court Hears. Tens of thousands of potential cases start the process to the court each year, but the Supreme Court hears very few. In recent years as few as 75 per year. Here’s an NYT article discussing the fact that the court chooses to hear fewer and fewer cases each year: The Case of the Plummeting Supreme Court Docket. At some point the lower courts make a decision, and whatever side looses is in a position to ask for a review of the decision – not because they disagree with it, but because there was some procedural error in the decision. This could mean – among other things - that evidence was obtained in violation of the 4th Amendment, or the law a person was convicted if violating is in violation of the Constitution. Petition for Certiorari Cases from a lower court can be appealed by the losing party. This is not based on a request that the case be reheard simply because they lost, but based on the argument that a procedural error occurred at the lower level. Specifically they request that a court issue a Writ of Certiorari. This is a writ where a higher court asks a lower court to send it the trial and appellate records so the court can search for errors. The first step for federal cases is for an appeal to be made to the appropriate Circuit Court of Appeals. Each court is staffed with a numbers of judges that are available to hear the appeals. Here’s the map again. Note the numbers: Texas is in the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals along with Louisiana and Mississippi. It’s headquartered in New Orleans. Not surprisingly it is considered to be one of the most conservative courts in the nation. Click here for it’s website. Click here for oral arguments from th the 5 Circuit. And here for the 5th Circuit’s opinion page. Here’s a map of the appellate courts in Texas. These are the courts where appeals to the decisions of state courts are made. In the federal courts cases are assigned to a panel of three randomly picked judges who then hear the appeals made by lawyers on either side of the case. No new evidence is considered, only arguments related to the process in the trial. Whichever side looses the ruling of the 3 judge panel can petition for the case to be reheard by all the judges of the circuit court – a rehearing en banc – or petition the Supreme Court. Again, asking the court to issue a Writ of Certiorari. This is done by filing a petition for certiorari within 90 days of the decision. The petition allows the plaintiff the opportunity to convince the court that they should hear the case. The petition is received by the circuit justice, which is the member of the Supreme Court with jurisdiction over a specific circuit. All cases from that circuit are reviewed by that Justice. Click for detail on circuit allotments of Supreme Court Justices. And here for a map. The 5th Circuit Court of Appeals is allotted to Antonin Scalia. The side that won in the circuit court of appeals ruling can file a brief in opposition. While this is occurring, outside groups can submit briefs arguing why the court should or should not hear the case. After reviewing the case, the Justices can add to the list of cases they intend to talk about in their next conference. Much of the work done in reviewing the cases is done by law clerks. From USCourts.gov: “Each Justice is permitted to have between three and four law clerks per Court term. These are individuals who, fairly recently, graduated from law school, typically, at the top of their class from the best schools. Often, they have served a year or more as a law clerk for a federal judge. Among other things, they do legal research that assists Justices in deciding what cases to accept; help to prepare questions that the Justice may ask during oral arguments; and assist with the drafting of opinions. Some members of the Supreme Court once served as a law clerk on the court for a previous justice. Click here for a complete list. If four justices choose to hear a case in the conference, the case it is placed on the court’s calendar. This process is referred to as The Rule of Four. Merits Stages If the case is denied, then the ruling of the Circuit Court prevails. If it is accepted, it is placed on the orders list and the parties to the case are required to file new sets of briefs. They are now required to state why they should win the case. If you won at the lower level, its generally bad news if the Supreme Court agrees to hear your case. More often than not the case will be overturned. The petitioner – the party that initiates the process – sends a legal brief. This is called the petitioners brief. They have 45 days to do so once certiorari has been granted. The respondent – the party that won at the lower level – can also if it chooses. It doesn’t have to. This is called the reply brief. The court also considers amicus briefs – friend of the court briefs – sent in by parties not involved in the specific case, but interested in the outcome. To get an idea of the range of groups that submit amicus briefs – as well as all other aspects of the process in actuality – click here for Scotusblog’s page on Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores. This is an area where interest groups can have influence on a court’s decision. Sometimes the U.S. Government may see an interest in one side of the case and may submit an amicus brief. The U.S. Solicitor General is responsible for preparing and submitting the brief. They can also argue part of the case if they wish. This sets the stage for oral arguments. Oral Arguments This process can occur at any point in the year. When the court convenes on the first Monday in October they begin to set a schedule for hearing arguments in the cases they have already agreed to hear. They generally hear cases through the following April. The court usually grants one hour for arguments, with 30 minutes for each side. The Chief Justice controls clock. Chief Justice Rehnquist held to a strict 30 minute schedule, the current Chief Justice Roberts tends to allow the argument to continue until it comes to a conclusion. Sometimes the time can be divided among different people – including the Solicitor General. Oral arguments can be pretty open ended. The Justices can be actively involved in questioning the attorneys. These tend to be recorded, so they can be heard after the fact. The court has never allowed its arguments to be video taped. Click here for the Supreme Court page with audio of the arguments made available. Click here for the audio of the court’s argument in Citizens United v the FEC. Transcripts of the oral arguments are also made available quickly after the argument is over. Click here to get them. After oral arguments are held, conferences are held internally which result in votes where the justices line up for and against the petitioner. Decision After the argument is over, the Justices meet privately to vote on each case. Often the decision about who won and lost is known immediately. What takes time is the writing of the decision. Sometimes votes can change during that process. The senior justice in the majority decides who will write the majority decision. This assumes there is a majority decision. Sometimes there may be a majority on one side, but for different reasons, so there is no one opinion with at least 5 Justices signing on to it. This is called a plurality opinion. If there is a majority decision, then the court is in a position to impact constitutional interpretation. This is especially true if the court issues a unanimous decision. Brown v Board of Education was a unanimous decision. It was able to overturn the “separate but equal doctrine” authoritatively. A plurality opinion can provide a winner, but without a clear understanding why that is the case. These decisions explain why a vote was made, but cannot change precedence, or reinterpret constitutional language. Some Justices write concurring opinions. These are written by Justice’s that agree with the direction of a vote – whether the petitioner should win or lose – but disagree as to why. Or they might sign onto the majority decision but may have their own reason for doing so. This allows them to lay that out. Those in the minority can write dissenting opinions. These explain why the majority was in error, and provides the opportunity for those in the minority to introduce ideas that can potentially grow in strength and influence future decisions. Example: Justice Harlan’s dissent in Plessy v Ferguson would provide the basis for the majority decision in Brown v Board. Oliver Wendell Holmes’ dissent in Abrams v the US set the stage for the expansion of free speech over the course of the 20th Century. Congressional and Executive Response It’s generally held that the Supreme Court has the last word on the meaning of the law and the Constitution. This is what it means to say that the role of the court is to interpret the law. But the other two branches – the political branches – have opportunities to respond to decisions they disagree with. I want to conclude with a brief look at some of the ways each institution can respond to Supreme Court decisions they disagree with. Changing the law. If Congress disagrees with how the court interpreted a law (something it has previously passed) it can rewrite the law to account for the interpretation. Example: The Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009. In 2007, the Supreme Court ruled in Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. that a lawsuit against an employer accused of engaging in gender pay discrimination was invalid because it was not filed in time. Congress simply extended the time limit, which negated future such decisions. But this can be difficult to do in all cases, especially if Congress is divided. Democrats and Republicans often disagree with what court decisions should be addressed and which should be allowed to stand. Changing the bureaucratic rule If the court rules against the use of executive power, the rule can be amended in order to comply with the decision. Appointments to the Courts As explained elsewhere, the principle way that the executive (with some checks by the legislature) can influence the courts is through the power of appointment. This is more likely to happen when voting decisions by the electorate help one party dominate the political branches for a long enough period of time to tip the ideological balance in their favor. Sometimes this occurs because voters are mobilized because of Supreme Court cases. One example: From the NYT: Appeals Courts Pushed to Right by Bush Choices.