Learning Target: I can analyze and discuss a primary source in

advertisement

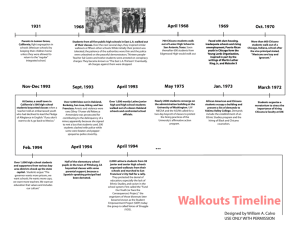

Monday, March 17, 2014 The Chicano Movement Learning Target: I can analyze and discuss a primary source in order to describe the goals, strategies and impacts of the Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 70s. Do Now: Fill out your learning log for LGBT Americans. Use your notes from “After Stonewall” and a partner if you get stuck. Reading Preview: Look at the picture below. Use it to make observations and a prediction about what you think we’ll be discussing about the Chicano movement today. Observe: What do you see in the picture? What do you think the people are doing? What do they want? What do you predict we’ll see Latino Americans fighting for today? Monday, March 17, 2014 The Chicano Movement Reading Assignment: As you read your document, annotate by highlighting the goals of the movement, underlining the strategies used by the movement, and boxing the impacts of the movement. After 20 minutes, you will share with your partners. Document Interview with Sal Castro and Mario T. Garcia A Tale of Two Schools El Plan de Santa Barbara: A Chicano Plan for Higher Education Goals Strategies Impacts Monday, March 17, 2014 The Chicano Movement Interview: Sal Castro and Mario T. Garcia on Grassroots Activism Posted by Alex on 30 March 2011, 9:54 am In a recent interview, Sal Castro and Mario T. García discuss the significance of “blowouts,” or walkouts, in the education of Chicano students in East L.A. and the subsequent urban Chicano movement of the 1960s and 70s. In Blowout!: Sal Castro and the Chicano Struggle for Educational Justice, the authors employ the testimonial style to further discuss the importance of grassroots activism can make in students’ lives. Below, the authors reflect on Castro’s influence as an educator and activist who helped Mexican American youth find their voice and speak out against the discrimination they experienced, ultimately making a great difference in educational justice. The authors are speaking at the University of Notre Dame today and will be at the LA Festival of Books and other California venues in the coming months. Check the full events listing for details. Q: Sal, as a Chicano American who himself grew up in East L.A., can you describe what education was like for Chicano and Chicana students before the blowouts? A: Public education in East L.A. before the walkouts reflected the legacy of the so-called “Mexican Schools” in the Southwest and southern California going back to the early 20th century when mass immigration from Mexico began. As immigrants found work in urban and rural areas, public schools sprang up that were called Mexican Schools. These were segregated schools for Mexicans with limited and inferior education. Despite many years of effort by Mexican Americans to change these schools, including legal struggles, the basic nature of these schools continued into the 1960s. These schools were characterized by high dropout rates, a heavily vocational curriculum and a marginalized academic one, low reading scores, few academic counselors, overcrowded conditions, and worst of all, low expectations of the Chicano students by a mostly Anglo or white faculty. Moreover, these schools in no way reflected the ethnic and cultural background of the kids. These were the conditions we faced in 1968 when the students decided to take things into their own hands and attempt to force changes by resorting to a student strike. Q: Mario, what were the L.A. blowouts, and when did they occur? Besides the systemic problems Sal has described, was there an immediate cause for them? A: The L.A. blowouts, or walkouts, occurred in early March 1968 and involved thousands of Mexican American students in the East L.A. high schools and middle schools who engaged in student strikes for a week by walking out of their classes to protest the inferior conditions in their schools. The immediate cause of the blowouts was that students at Wilson High School in East L.A. had a school play, “Barefoot in the Park,” cancelled because the principal, after going to the last rehearsal, decided that the play contained sexual innuendos. The students in the play protested and spontaneously staged a walkout of their school and were joined by many others. The blowouts had commenced even though Sal Castro and the student leaders had not planned for the strike at that time. But after Wilson students went out, Sal and the leaders had no choice but to engage in a total walkout. Q: How did these walkouts come by the name of “blowouts”? A: Mario: John Ortiz, one of the walkout leaders at Garfield High School, coined the term “blowout.” A jazz fan, Ortiz borrowed this from a jazz term that refers to stressing a particular note or giving your music a particular and forceful emphasis. He then transferred the term to the Q: Sal, what were the early influences on your life that led to your later activism? A: The early influences were not only my bad experiences in the public schools, but also in the Catholic schools that I attended. How early elementary teachers seemed to convey prejudicial attitudes toward me and how even in my Catholic high school, there was a tracking system where most Mexican American students were assigned the least challenging academic curriculum. I was also influenced by the discrimination and racism against Mexican Americans in the community, including that against my own father, who was deported in the mid-1930s as part of a larger deportation campaign to round-up and send close to half a million Mexicans back to Mexico, including U.S. born children, under the unfair justification that “illegal aliens” were taking jobs away from “real Americans,” as well as spreading diseases and crime. After high school, when I was drafted into the Army, I witnessed the Jim Crow system in the South where I was stationed for a while. Later in Dallas, in a layover at the airport, I was refused service at a restaurant because I was Mexican American, even though I was wearing my U.S. Army uniform. After I returned and went to college, I heard professors in my classes at L.A. State express gross stereotypes about Mexican Americans and why they failed in school. My own early experiences as a teacher in the early 1960s at Belmont High School exposed me to the full problems of the Mexican Schools, with their high dropout rates and non-academic tracks for most Mexican Americans, as well as other Monday, March 17, 2014 The Chicano Movement problems. All of this motivated me to become a committed teacher who would not just complain about these conditions but attempt to change them by my actions. Q: Sal, what did you see as key to improving the educational experience and lives of Chicano and Chicana Americans? A: I think that the first thing that had to change was the perception Mexican American students had of themselves. They had to begin to feel good and secure about themselves. They had to possess a positive image of themselves, their parents, and their communities. What also had to change was the curriculum. It needed to integrate Mexican and Chicano history and culture and show the positive contributions of people of Mexican descent to the United States For example, showing how Mexican Americans have patriotically supported and participated in America’s wars going all the way back to the American Revolution, the Civil War, World War I, World War II, Korea, Vietnam, and today in Iraq and Afghanistan. Once they feel good about themselves, Chicano/Latino kids can then go on to a full academic curriculum where they are encouraged to go to college and to become professionals who also give back to their communities. Q: Mario, you describe the blowouts as part of the general civil rights movement and Vietnam-era protests that were sweeping the nation. What was unique or different about the blowouts? A: What was unique about the blowouts was that this historical event represented the beginnings of the urban Chicano Movement as opposed to that of the rural movement led by César Chávez and the farm workers. The urban Chicano Movement would become, not only in L.A. but throughout the Southwest, the central battleground of the Chicano Movement for both civil rights and community empowerment and a new, more empowering identity. Further, the blowouts and the Chicano Movement represented the oppositional struggles by Chicanos in a period of political engagement—the 1960s—that most historians have only viewed from white and black perspectives, excluding the major role of Chicanos in the protests of this era. I would further add that the specific uniqueness of the blowouts was the role of high school students in these protests. Most attention to the student protests of the ’60s has been focused on college students and not on high school students. Q: Sal, what problems did the blowouts begin to address, and what problems remain to be solved 43 years later? What is needed now to improve education and the prospects for Chicano and Chicana Americans? A: The blowouts began to address the very nature of the Mexican Schools or inner city schools that, instead of creating opportunities for educational and economic mobility, reinforced a status quo which valued people of Chicano/Latino descent primarily for being cheap labor. The blowouts brought attention to the fact that although education can be a panacea for social ills, education in schools like the Mexican Schools can also be the problem. More specifically, the blowouts brought attention to the high dropout rates in these schools and the many other problems we have mentioned. Many of these problems remain, including a lack of curriculum for Chicano/Latino kids to reinforce their particular ethnic backgrounds. We have made some progress: more of our kids are attending college, there are more Latino teachers and administrators and a stronger academic curriculum, etc., but with a still growing Latino immigrant population and a new generation of kids going to these schools, many of the earlier problems continue in one way or another. In addition, schools in the inner city are caught in battles over school budgets, and they usually lose out, remaining underfunded and under-supported in other resources. What is needed is a renewed struggle by our communities and our students to force new changes to improve the schools. One of the lessons of the blowouts was that only student and community pressure brings attention to the problems and results in change. Nothing of substance ever trickles from above; it starts from below. Am I advocating new blowouts? Well why not? Only dramatic action seems to be listened to in our society. Go for it. Blowout! Q: Mario and Sal, why are the blowouts important today? A: Mario: The blowouts represent a major event of the Chicano Movement and one of the most significant examples of high school student protest in United States history. The blowouts stress that the struggle for educational justice is critical to American democracy then and now. Sal: The blowouts are important because of the courage of the kids and what it says about those who have struggled to make life better for others. The students knew that whatever changes they could bring about in the schools would not affect them but they hoped it would affect those who came behind them. They struggled for other Chicanos that they didn’t even know. What this means to me is that courage and dedication is central to bringing about change, and this is what the blowouts and the Chicano Movement represented and perhaps this is still an example for today’s students and others. Monday, March 17, 2014 The Chicano Movement A Tale of Two Schools Vocabulary "Americanization": The practice of teaching immigrant children about American culture and values in segregated classes or schools. Anglo: A White U.S. resident who is not of Hispanic/Latino descent. Chicano: A U.S. resident of Mexican descent. Class action suit: A legal undertaken by one or more plaintiffs on behalf of themselves and all other persons having an identical interest in the alleged wrong. Colonia: A segregated residential community of Mexican American workers and their families. Latino: A person of Latin American origin living in the U.S., including but not limited to Mexican Americans. Naturalized: Admitted into citizenship. In the early 1900s, Mexican Americans, or Chicanos, in California and the Southwest were excluded from "Whites Only" theaters, parks, swimming pools, restaurants, and even schools. Immigrants from Mexico waged many battles against such discriminatory treatment, often risking their jobs in fields and factories and enduring threats of deportation. In 1945, one couple in California won a significant victory in their struggle to secure the best education for thousands of Chicano children. In the fall of 1944, Soledad Vidaurri took her children and those of her brother, Gonzalo Méndez, to enroll at the 17th Street School in Westminster, Calif. Although they were cousins and shared a Mexican heritage, the Méndez and Vidaurri children looked quite different: Sylvia, Gonzalo Jr. and Geronimo Méndez had dark skin, hair and eyes, while Alice and Virginia Vidaurri had fair complexions and features. An administrator looked the five children over. Alice and Virginia could stay, he said. But their dark-skinned cousins would have to register at the Hoover School, the town's "Mexican school" located a few blocks away. Furious at such blatant discrimination, Vidaurri returned home without registering any of the children in either school. In the 1940s, Westminster was a small farming community in the southern part of the state. Lush citrus groves, lima bean fields and sugar beet farms stretched in every direction from a modest downtown business district. Most of the men and women working in those fields were first- and second-generation immigrants from Mexico who were employed by white ranchers. Like many California towns at the time, Westminster really comprised two separate worlds: one Anglo, one Mexican. While Anglo growers welcomed Chicano workers in their fields during times of economic prosperity, they shut them out of mainstream society. Most people of Mexican ancestry lived in colonias -- segregated residential communities -- on the fringes of Anglo neighborhoods. The housing was often substandard, with inadequate plumbing and often no heating. Roads were unpaved and dusty. Westminster's Hoover School was in the heart of one such colonia and was attended by the children of Mexican field laborers. A small frame building at the edge of a muddy cow pasture, the Hoover School stood in stark contrast to the sleek 17th Street School, with its handsome green lawns and playing fields.The Westminster School District was not alone in discriminating against Chicano students. At the time, more than 80 percent of school districts in California with large Mexican populations practiced segregation. The segregation of Chicano children was also widespread in Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. The Mexican schools were typically housed in run-down buildings. They employed less-experienced teachers than the Anglo schools. Chicano children were given shabbier books and equipment than their white peers and were taught in more crowded classrooms. Perhaps the greatest difference between the schools, however, was in their curricula. While geometry and biology were taught at the Anglo schools, classes at the Mexican schools focused on teaching boys industrial skills and girls domestic tasks. Many Anglo educators did not expect, or encourage, Chicano students to advance beyond the 8th grade. Instead, the curriculum at the Mexican schools was designed, as one district superintendent put it, "to help these children take their place in society." That "place" was the lowest rung of the economic ladder, providing cheap, flexible labor for the prospering agricultural communities of California and the Southwest. But Chicano men and women had different ideas about their children's futures. Like other immigrant groups, Chicano field laborers believed education was the ticket to a better life in America, a way out of the heat and dust of the fields. Gonzalo and Felícitas Méndez knew well the difficult life of field laborers. Both had emigrated to the United States as young children. Like thousands of Mexicans in the early 20th century, Gonzalo's family fled political turmoil in their native country. They left behind a successful ranch in Chihuahua and found jobs as day laborers in the citrus groves of southern California. Monday, March 17, 2014 The Chicano Movement The Mendezes were forced to abandon their education in grade school in order to support their families. But they had higher hopes for young Sylvia, Gonzalo Jr. and Geronimo. And when Soledad Vidaurri told her brother and sister-in-law their children were refused admission to the 17th Street School because they -- unlike her own children -- didn't look "white enough," Gonzalo and Felícitas were outraged. Gonzalo and Felicitas were ready to do battle with the Westminster School District for the sake of their children's education. Realizing other Chicano families in the community faced the same problem, the Méndezes organized a group of Mexican parents to protest the segregation of their children in the shabbier school. Together, they sent a letter to the board of education demanding that the schools be integrated. Their request was flatly denied. Gonzalo continued to petition school district administrators. Worn down by his persistence, the school superintendent finally agreed to make an exception for the Méndez children and admit them to the Anglo school. But the Méndezes immediately rejected his offer. The school would have to admit all of the Chicano children in the community or none of them. The Méndezes hired a civil rights attorney, David Marcus, who had recently won a lawsuit on behalf of Mexican Americans in nearby San Bernardino seeking to integrate the public parks and pools. The Méndezes also learned parents in other school districts were fighting segregation too. Marcus suggested they join forces, and on March 2, 1945, the Méndezes and four other Mexican American families filed a class action suit against the Westminster, Garden Grove, El Modena and Santa Ana boards of education on behalf of 5,000 Mexican American children attending segregated, inferior schools. The Méndezes threw themselves into the trial preparations. Gonzalo took a year off work to organize Latino men and women and gather evidence for the case. Every day, he and David Marcus drove across Orange County's patchwork of vegetable farms and citrus groves, stopping in the colonias. They knocked on doors and tried to convince Mexican American parents and their children to testify in court. Finally, the trial date arrived. Now it was up to the courts to decide if the Latino men and women who helped California's agricultural economy grow and thrive were entitled to the same rights as those who prospered from their labor. During the trial, the attorney for the school boards, Joel Ogle, pointed out the 1896 Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson gave legal sanction to racial segregation, provided the separate facilities for different races were equal. Furthermore, Ogle maintained, there were sound educational and social advantages to segregated schooling. The "Mexican schools" gave special instruction to students who didn't speak English and who were unfamiliar with American values and customs. Such "Americanization" programs benefited both Anglos and Mexicans, Ogle argued. But this educational rationalization for segregation was undermined by the testimony of 9-year-old Sylvia, 8-year-old Gonzalo and 7year-old Geronimo Méndez. All spoke fluent English, as did many of the other children who attended the Hoover School. In fact, further testimony revealed no language proficiency tests were ever given to Chicano students. Rather, enrollment decisions were based entirely on last names and skin color, as evidenced by the experience of the Méndez children and their cousins. The racist underpinnings of such "Americanization" programs became apparent when James L. Kent, the superintendent of the Garden Grove School District, took the stand. Under oath, Kent said he believed people of Mexican descent were intellectually, culturally and morally inferior to European Americans. Even if a Latino child had the same academic qualifications as a white child, Kent stated, he would never allow the Latino child to enroll in an Anglo school. U.S. District Court Judge Paul J. McCormick was appalled by Kent's blatant bigotry. On February 18, 1946, he ruled in favor of the plaintiffs. In his opinion, McCormick pointed out segregation "fosters antagonisms in the children and suggests inferiority among them where none exists." Because the separate schools created social inequality, he reasoned, they were in violation of the students' constitutional rights. He also pointed out there was no sound educational basis for the segregation of Anglo and Mexican students since research showed segregation worked against language acquisition and cultural assimilation. The Orange County school boards filed an appeal. By now, however, the Méndez lawsuit was drawing national attention. Civil rights lawyers in other states were watching the proceedings closely. For half a century, they had been trying to strike down the "separate but equal" doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson, and they thought Méndez just might be the test case to do it. Among those following the suit was a young African American attorney named Thurgood Marshall. Marshall and two of his colleagues from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) submitted an amicus curiae -- "friend of the court" -- Monday, March 17, 2014 The Chicano Movement brief in the appellate case. Among the other groups submitting amicus briefs were the League of United Latin American Citizens, the Japanese American Citizens League and the Jewish Congress. On April 14, 1947, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco upheld the lower court decision. The court stopped short, however, of condemning the "separate but equal" doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson. The NAACP and other groups eagerly waited for Orange County school officials to file an appeal that would bring the case before the U.S. Supreme Court. But lawyers for the school read the writing on the wall: Mainstream public opinion had shifted, and the era of segregation was coming to a close. The defense decided not to appeal the decision further. An opportunity to overturn Plessy would have to wait. Even if it would not rewrite the law of the land, Méndez v. Westminster still had a significant regional impact. Like a pebble tossed into a pond, the legal victory sent ripples of change throughout the Southwest. In more than a dozen communities in California alone, Mexican Americans filed similar lawsuits. Chicano parents sought and won representation on school boards and gained a voice in their children's education. The decision also prompted California Gov. Earl Warren to sign legislation repealing a state law calling for the segregation of American Indian and Asian American students. Seven years later, the NAACP did find a successful test case to reverse Plessy v. Ferguson. Thurgood Marshall argued the landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka before the U.S. Supreme Court, presenting the same social science and human rights theories he outlined in his amicus curiae brief for the Méndez case. Former California Gov. Earl Warren, now a chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, wrote the historic opinion finally ending the legal segregation of students on the basis of race in American schools in 1954. In September of 1947, Sylvia, Gonzalo Jr. and Geronimo Méndez enrolled at the 17th Street School in Westminster without incident. Integrated schools also opened that fall in Garden Grove, El Modena and Santa Ana. Felícitas and Gonzalo Méndez quietly resumed their work. At the time, neither really considered the full impact of their legal victory; they were content just to have righted a wrong in their community and to have protected their children's future. In 1964, Gonzalo Méndez died of heart failure. Felícitas continued to live in Southern California until her death in 1998. Sadly, neither Méndez v. Westminster nor Brown v. Board of Education led to the complete integration of American schools. The long legacy of segregation has left its mark on our current educational system, and integration and equity are issues schools are still grappling with today. In Santa Ana, Calif. -- one of the districts named in the Méndez desegregation lawsuit more than 50 years ago -a new school opened in the fall of 2000 honoring Gonzalo and Felícitas Méndez, two civil rights pioneers in the continuing struggle to provide equal educational opportunities for all of America's children. Monday, March 17, 2014 The Chicano Movement El Plan de Santa Barbara (Abbreviated) El Plan de Santa Bárbara: A Chicano Plan for Higher Education was written by the Chicano Coordinating Council on Higher Education as a manifesto for the implementation of Chicano Studies educational programs throughout the state of California. The Plan was adopted in April 1969 at a symposium held at the University of California, Santa Barbara, USA. The 155-page document outlines proposals for a curriculum in Chicano Studies, the role of community control in Chicano education, and the necessity of Chicano political independence. The document retains visibility as the founding document of the Chicano student group MEChA Manifesto For all peoples, as with individual, the time comes when they must reckon with their history. For the Chicano the present is a time of renaissance, of renacimiento. Our people and our community, el barrio and la colonia, are expressing a new consciousness and a new resolve. Recognizing the historical tasks confronting our people and fully aware of the cost of human progress, we pledge our will to move. We will move forward toward our destiny as a people. We will move against those forces which has denied us freedom of expression and human dignity. Throughout history the quest for cultural expression and freedom has taken the form of a struggle… For decades Mexican people in the United States struggle to realize the ''American Dream''. And some, a few, have. But the cost, the ultimate cost of assimilation, required turning away from el barrio and la colonia. In the meantime, due to the racist structure of this society, to our essentially different life style, and to the socio-economic functions assigned to our community by Anglo-American society - as suppliers of cheap labor and dumping ground for the small-time capitalist entrepreneur- the barrio and colonia remained exploited, impoverished, and marginal. As a result, the self-determination of our community is now the only acceptable mandate for social and political action; it is the essence of Chicano commitment. Culturally, the word Chicano, in the past a pejorative and class-bound adjective, has now become the root idea of a new cultural identity for our people. It also reveals a growing solidarity. The widespread use of the term Chicano today signals a rebirth of pride and confidence. Chicanismo simply embodies and ancient truth: that a person is never closer to his/her true self as when he/she is close to his/her community… Political Action Introduction For the Movement, political action essentially means influencing the decision-making process of those institutions which affect Chicanos, the university, community organizations, and non-community institutions. Political action encompasses the elements which function in a progression: political consciousness, political mobilization, and tactics. Each part breaks down into further subdivisions. Before continuing with specific discussions of these three categories, a brief historical analysis must be formulated. Historical Perspective The political activity of the Chicano Movement at colleges and universities to date has been specifically directed toward establishing Chicano student organizations (UMAS, MAYA, MASC, M.E.Ch.A., etc.) and institutionalizing Chicano Studies programs. A variety of organizational forms and tactics have characterize these student organizations. One of the major factors which led to political awareness in the 60's was the clash between Anglo-American educational institutions and Chicanos who maintained their cultural identity. Another factor was the increasing number of Chicano students who became aware of the extent to which colonial conditions characterized their communities. The result of this domestic colonialism is that the barrios and colonias are dependent communities with no institutional power base and significantly influencing decision-making. Within the last decade, a limited degree of progress has taken place in securing a base of power within educational institutions. Monday, March 17, 2014 The Chicano Movement Other factors which affected the political awareness of the Chicano youth were: the heritage of the Chicano youth movements of the 30's and 40's; the failure of the Chicano political efforts of the 40's and 50's; the bankruptcy of the Mexican- American pseudo-political associations; and the disillusionment of Chicano participants in the Kennedy campaigns. Among the strongest influences of Chicano youth today have been the National Farm Workers Association, the Crusades for Justice, and the Alianza Federal de Pueblos Libres, The Civil Rights, the Black Power, and the Anti-war movements were other influences. As political consciousness increased, there occurred a simultaneously a renewed cultural awareness which, along with social and economical factors, led to the proliferation of Chicano youth organizations. By the mid 1960's, MASC, MAYA, UMAS, La Vida Nueva, and M.E.Ch.A. appeared on campus, while the Brown Berets, Black Berets, ALMA, and la Junta organized the barrios and colonias. These groups differed from one another depending on local conditions and their varying state of political development. Despite differences in name and organizational experience, a basic unity evolved. These groups have had a significant impact on the awareness of large numbers of people, both Chicano and non-Chicano. Within the communities, some public agencies have been sensitized, and others have been exposed. On campuses, articulation of demands and related political efforts have dramatized NUESTRA CAUSA. Concrete results are visible in the establishment of corresponding supportive services. The institutionalization of Chicano Studies marks the present stage of activity; the next stage will involve the strategic application of university and college resources to the community. One immediate result will be the elimination of the artificial distinction which exist between the students and the community. Rather than being its victims, the community will benefit from the resources of the institutions of higher learning. Political Consciousness Commitment to the struggle for Chicano liberation is the operative definition of the ideology used here. Chicanismo involves a crucial distinction in political consciousness between a Mexican American (or Hispanic) and a Chicano mentality. The Mexican American or Hispanic is a person who lacks self-respect and pride in one's ethnic and cultural background. Thus, the Chicano acts with confidence and with a range of alternatives in the political world. He is capable of developing and effective ideology through action. Mexican Americans (or Hispanics) must be viewed as potential Chicanos. Chicanismo is flexible enough to relate to the varying levels of consciousness within La Raza. Regional variations must always be kept in mind as well as the different levels of development, composition, maturity, achievement, and experience in political action. Cultural nationalism is a means of total Chicano liberation. There are definite advantages to cultural nationalism, but no inherent limitations. A Chicano ideology, especially as it involves cultural nationalism, should be positively phrased in the form of propositions to the Movement. Chicanismo is a concept that integrates selfawareness with cultural identity, a necessary step in developing political consciousness. As such, it serves as a basis for political action, flexible enough to include the possibility of coalitions. The related concept of La Raza provides an internationalist scope of Chicanismo, and La Raza Cosmica furnishes a philosophical precedent. Within this framework, the Third World concept merits consideration. Political Mobilization Political mobilization is directly dependent on political consciousness. As political consciousness develops, the potential for political action increases. The Chicano student organization in institutions of higher learning is central to all effective political mobilization. Effective mobilization presupposes precise definition of political goals and of the tactical interrelationships of roles. Political goals in any given situations must encompass the totality of Chicano interests in higher education. The differentiations of roles required by a given situation must be defined on the basis of mutual accountability and equal sharing of responsibility. Furthermore, the mobilization of community support not only legitimizes the activities of Chicano student solidarity in axiomatic in all aspects of political action. Since the movements is definitely of national significance and scope, all student organizations should adopt one identical name throughout the state and eventually the nation to characterize the common struggle of La Raza de Aztlan. The net gain is a step toward greater national unity which enhances the power in mobilizing local campus organizations. Monday, March 17, 2014 The Chicano Movement When advantageous, political coalitions and alliances with non-Chicano groups may be considered. A careful analysis must precede the decision to enter into a coalition. One significant factor is the community's attitude toward coalitions. Another factor is the formulation of a mechanism for the distribution of power that ensures maximum participation in decision making: i.e., formulation of demands and planning of tactics. When no longer politically advantageous, Chicano participation in the coalition ends. Campus Organizing: Notes on M.E.Ch.A. Introduction M.E.Ch.A. is a first step to tying the students groups throughout the Southwest into a vibrant and responsive network of activists who will respond as a unit to oppression and racism and will work in harmony when initiating and carrying put campaigns of liberation for our people. As of present, wherever one travels throughout the Southwest, one finds that there are different levels of awareness of different campuses. The student movement is to a large degree a political movement and as such must not elicit from our people the negative reason. To this end, then we must re-define politics for our people to be a means of liberation. The political sophistication of our Raza must be raised so that they do not fall prey to apologists and vendidos whose whole interest if their personal career of fortune. In addition, the student movement is more than a political movement, it is cultural and social as well. The spirit of M.E.Ch.A. must be one of hermandad and cultural awareness. The ethic of profit and competition, of greed and intolerance, which the Anglo society offers must be replaced by our ancestral communalism and love for beauty and justice. M.E.Ch.A. must bring to the mind of every young Chicano that the liberations of this people from prejudice and oppression is in his hands and this responsibility is greater than personal achievement and more meaningful that degrees, especially if they are earned at the expense of his identity and cultural integrity. M.E.Ch.A., then, is more than a name; it is a spirit of unity, of brotherhood, and a resolve to undertake a struggle for liberation in society where justice is but a word. M.E.Ch.A. is a means to an end. Function of M.E.Ch.A.- To the Student To socialize and politicize Chicano students of their particular campus to the ideals of the movement. It is important that every Chicano student on campus be made to feel that he has a place on the campus and that he/she has a feeling of familia with his/her Chicano brothers, and sisters. Therefore, the organization in its flurry of activities and projects must not forget or overlook the human factor of friendship, understanding, trust, etc. As well as stimulating hermanidad, this approach can also be looked at in more pragmatic terms. If enough trust, friendship, and understanding are generated, then the loyalty and support can be relied upon when a crisis faces the group or community. This attitude must not merely provide a social club atmosphere but the strengths, weaknesses, and talents of each member should be known so that they may be utilized to the greatest advantage. Know one another. Part of the reason that students will come to the organization is in search of self-fulfillment. Give that individual the opportunity to show what he/she can do. Although the Movement stresses collective behavior, it is important that the individual be recognized and given credit for his/her efforts. When people who work in close association know one another well, it is more conductive to self-criticism and re-evaluation, and this every M.E.Ch.A. person must be willing to submit to. Periodic self-criticism often eliminates static cycles of unproductive behavior. It is an opportunity for fresh approaches to old problems to be surfaces and aired; it gives new leadership a chance to emerge; and must be recognized as a vital part of M.E.Ch.A. M.E.Ch.A. can be considered a training ground for leadership, and as such no one member or group of members should dominate the leadership positions for long periods of time.This tends to take care of itself considering tie transitory nature of students. Recruitment and Education Action is the best organizer. During and immediately following direct action of any type--demonstrations, marches, rallies, or even symposiums and speeches-- new faces will often surface and this is where much of the recruiting should be done. New members should be made to feel that they are part of the group immediately and not that they have to go through a period of warming up to the old membership. Each new member should be given a responsibility as soon as possible and fitted into the scheme of things according to his or her talents and interests. Monday, March 17, 2014 The Chicano Movement Since the college student is constantly faced with the responsibility of raising funds for the movements, whether it be for legal defense, the grape boycott, or whatever reason, this is an excellent opportunity for internal education. Fund-raising events should always be educational. If the event is a symposium or speech or debate, is usually an excellent opportunity to spread the Chicano Liberation Movement philosophy. If the event is a pachanga or tardeada or baile, this provides an excellent opportunity to practice and teach the culture in all its facets. In addition, each M.E.Ch.A. chapter should establish and maintain an extensive library of Chicano materials so that the membership has ready access to material which will help them understand their people and their problems. General meetings should be educational. The last segment of each regular meeting can be used to discuss ideological or philosophical differences, or some event in the Chicano's history. It should be kept in mind that there will always be different levels of awareness within the group due to the individual's background or exposure of the movement. This must be taken into consideration so as not to alienate members before they have had a chance to listen to the argument for liberation. The best educational device is being in the barrio as often as possible. More often than not the members of M.E.Ch.A. will be products of the barrio; but many have lost contact with their former surroundings, and this tie must be re-established if M.E.Ch.A. is to organize and work for La Raza. The following things should be kept in mind in order to develop group cohesiveness: 1) know the talents and abilities of each member; 2) every semester must be given a responsibility, and recognition should be given for their efforts; 3) of mistakes are made, they should become learning experiences for the whole group and not merely excuses for ostracizing individual members; 4) since many people come to M.E.Ch.A. seeking self-fulfillment, they must be seized to educate the student to the Chicano philosophy, culture, and history; 5) of great importance is that a personal and human interaction exist between members of the organization so that such things as personality clashes, competition, ego-trips, subterfuge, infiltration, provocateurs, cliques, and mistrust do not impede the cohesion and effectiveness of the group. Above all the feeling of hermanidad must prevail so that the organization is more to the members than just a club or a clique. M.E.Ch.A. must be a learning and fulfilling experience that develops dedication and commitment. A delicate but essential question is discipline. Discipline is important to an organization such as M.E.Ch.A. because many may suffer form the indiscretion of a few. Because of the reaction of the general population to the demands of the Chicano, one can always expect some retribution or retaliation for gains made by the Chicano, be it in the form of legal cations or merely economic sanction on the campus. Therefore, it becomes essential that each member pull his load and that no one be allowed to be dead weight. Carga floja is dangerous, and if not brought up to par, it must be cut loose. The best discipline comes from mutual respect, and therefore, the leaders of the group must enjoy and give this respect. The manner of enforcing discipline, however, should be left up to the group and the particular situation. Planning and Strategy Actions of the group must be coordinate in such a way that everyone knows exactly what he is supposed to do. This requires that at least rudimentary organizational methods and strategy be taught to the group. Confusion is avoid different the plans and strategies are clearly stated to all. The objective must be clear to the group at all times, especially during confrontations and negotiations. There should be alternate plans for reaching the objectives, and these should be explained to the group so that it is not felt that a reversal of position or capitulation has been carried out without their approval. The short, as well as the long, range values and effects of all actions should be considered before actions are taken. This assumes that their is sufficient time to plan and carefully map out actions, which brings up another point: don't be caught off guard, don't be forced to act out of haste; choose your own battleground and your own time schedule when possible. Know your power base and develop it. A student group is more effective if it can claim the support of the community and support on the campus itself form other sectors than the student population. Monday, March 17, 2014 The Chicano Movement The Function of M.E.Ch.A. - To the Campus Community Other students can be important to M.E.Ch.A. in supportive roles; hence, the question of coalitions. Although it is understood and quite obvious that the viability and amenability of coalition varies form campus to campus, some guidelines might be kept in mind. These questions should be asked before entering into any binding agreement. Is it beneficial to tie oneself to another group in coalition which will carry one into conflicts for which on is ill-prepared or involve one with issues on which one is ill-advised? Can one sagely go into a coalition where one group is markedly stronger than another? Does M.E.Ch.A. have an equal voice in leadership and planning in the coalition group? Is it perhaps better to enter into a loose alliance for a given issue? How does leadership of each group view coalitions? How does the membership? Can M.E.Ch.A. hold up its end of the bargain? Will M.E.Ch.A. carry dead weight in a coalition? All of these and many more questions must be asked and answered before one can safely say that he/she will benefit from and contribute to a strong coalition effort. Supportive groups. When moving on campus it is often well-advised to have groups who are willing to act in supportive roles. For example, there are usually any number of faculty members who are sympathetic, but limited as to the numbers of activities they will engage in. These faculty members often serve on academic councils and senates and can be instrumental in academic policy. They also provide another channel to the academic power structure and can be used as leverage in negotiation. However, these groups are only as responsive as the ties with them are nurtured. This goes not mean, compromise M.E.Ch.A.'s integrity; it merely means laying good groundwork before an issue is brought up, touching bases with your allies before hand. Sympathetic administrators. This a delicate area since administrators are most interested in not jeopardizing their positions and often will try to act as buffers or liaison between the administration and the student group. In the case of Chicano administrators, it should not be priori be assumed, he/she must be given the chance to prove his/her allegiance to La Causa. As such, he/she should be the Chicano's person in the power structure instead of the administration's Mexican-American. It is from the administrator that information can be obtained as to the actual feasibility of demands or programs to go beyond the platitudes and pleas of unreasonableness with which the administration usually answers proposals and demands. The words of the administrator should never be the deciding factor in students' actions. The student must at all time make their own decisions. It is very human for people to establish self-interest. Therefore, students must constantly remind the Chicano administrators and faculty where their loyalty and allegiance lie. It is very easy for administrators to begin looking for promotions just as it is very natural for faculty members to seek positions of academic prominence. In short, it is the students who must keep after Chicano and non-Chicano administrators and faculty to see that they do not compromise the position of the student and the community. By the same token, it is the student who must come to the support of these individuals if they are threatened for their support of the student. Students must be careful not to become a political level for others. Function of M.E.Ch.A. - Education It is a fact that the Chicano has not often enough written his/her own history, his/her own anthropology, his/her own sociology, his/her own literature. He/she must do this if he is to survive as a cultural entity in this melting pot society, which seeks to dilute varied cultures into a gray upon gray pseudo-culture of technology and materialism. The Chicano student is doing most of the work in the establishment of study programs, centers, curriculum development, entrance programs to get more Chicano into college. This is good and must continue, but students must be careful not to be co-opted in their fervor for establishing relevance on the campus. Much of what is being offered by college systems and administrators is too little too late. M.E.Ch.A. must not compromise programs and curriculum which are essential for the total education of the Chicano for the sake of expediency. The students must not become so engrossed in programs and centers created along establishes academic guidelines that they forget the needs of the people which these institutions are meant to serve. To this end, barrio input must always be given full and open hearing when designing these programs, when creating them and in running them. The jobs created by these projects must be filled by competent Chicanos, not only the Chicano who has the traditional credentials required for the position, but one who has the credentials of the Raza. To often in the past the dedicated pushed for a program only to have a vendido sharp-talker come in and take over and start working for his Anglo administrator. Therefore, students must demand a say in the recruitment and selection of all directors and assistant directors of student-initiated programs. To further insure strong if not complete control of the direction and running of programs, all advisory and steering committees should have both student and community components as well as sympathetic Chicano faculty as member. Tying the campus to the barrio. The colleges and universities in the past have existed in an aura of omnipotence and infallibility. It is time that they be made responsible and responsive to the communities in which they are located or whose member they serve. As has Monday, March 17, 2014 The Chicano Movement already been mentioned, community members should serve on all program related to Chicano interests. In addition to this, all attempts must be made to take the college and university to the barrio, whether it be in form of classes giving college credit or community centers financed by the school for the use of community organizations and groups. Also, the barrio must be brought to the campus, whether it be for special programs or ongoing services which the school provides for the people of the barrio. The idea must be made clear to the people of the barrio that they own the schools and the schools and all their resources are at their disposal. The student group must utilize the resources open to the school for the benefit of the barrio at every opportunity. This can be done by hiring more Chicanos to work as academic and non-academic personnel on the campus; this often requires exposure of racist hiring practices now in operation in may college and universities. When functions, social, or otherwise, are held in the barrio under the sponsorship of the college and university, monies should be spent in the Barrio. This applies to hiring Chicano contractors to build on campus, etc. Many colleges and universities have publishing operations which could be forced to accept barrio works for publication. Many other things could be considered in using the resources of the school to the barrio. There are possibilities for using the physical plant and facilities not mentioned here, but this is an area which has great potential. M.E.Ch.A. in the Barrio Most colleges in the southwest are located near or in the same town as a barrio. Therefore, it is the responsibility of M.E.Ch.A. members to establish close working relationship with organization in the barrio. The M.E.Ch.A. people must be able to take the pulse of the barrio and be able to respond to it. However, M.E.Ch.A. must be careful not to overstep its authority or duplicate the efforts of another organization already in the barrio. M.E.Ch.A. must be able to relate to all segments of the barrio, from the middle-class assimilationists to the vatos locos. Obviously, every barrio has its particular needs, and M.E.Ch.A. people must determine with the help of those in the barrio where they can be most effective. There are, however, some general areas which M.E.Ch.A. can involve itself. Some of them are: 1) policing social and governmental agencies to make them more responsive in a humane and dignified was to the people of the barrio; 2) carrying out research on the economic and credit policies of merchants in the barrio and exposing fraudulent and exorbitant establishment; 3) speaking and communicating with junior high and high school students, helping with their projects,teaching them organizational techniques, supporting their actions; 4) spreading the message of the movement by any media available - this means speaking, radio, television, local newspaper, underground paper, poster, art, theaters; in shot, spreading propaganda of the Movement; 5) exposing discrimination in hiring and renting practices and many other ares which the student because of his/her mobility, his/her articulation, and his/her vigor should take as hi/her responsibility. It may mean at timehaving to work in conjunction with other organizations. If this is the case and the project is one begun by the other organization, realize that M.E.Ch.A. is there as a supporter and should accept the direction of the group involved. Do not let loyalty to an organization cloud responsibility to a greater force - la Causa. Working in the barrio is an honor, but is also a right because we come form these people, and as, mutual respect between the barrio and the college group should be the rule. Understand at the same time, however, that there will initially be mistrust and often envy on the part of some in the barrio for the college student. This mistrust must be broken down by a demonstration of affection for the barrio and La Raza through hard work and dedication. If the approach is one of a dilettante or of a Peace Corps volunteer, the people will know it and act accordingly. If it is merely a cathartic experience to work among the unfortunate in the barrio - stay out. Of the community, for the community. Por la Raza habla el espiritu. Monday, March 17, 2014 The Chicano Movement