Gilgamesh PowerPoint #2: All I'm Losing is Me

advertisement

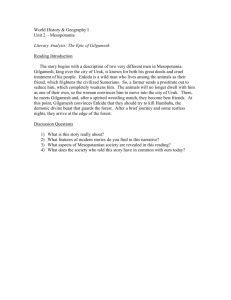

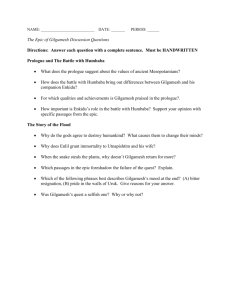

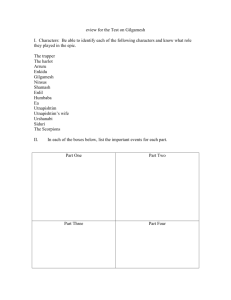

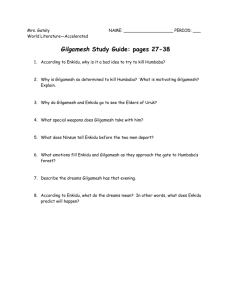

All I’m Losing is Me: Gilgamesh #2 Feraco Myth to Science Fiction 2 October 2009 Risky Business Once Enkidu comes in from the Steppe, the narrative shifts in a whiplash maneuver towards the battle in the forest with Humbaba Enkidu tries to convince Gilgamesh to abandon his quest, but to no avail This is how “Deal or No Deal” relates to Gilgamesh: Our hero doesn’t know what x or y stand for, and chooses to flip the coin anyway It is Humbaba who has taken your strength, Gilgamesh spoke out, anxious For the journey. We must kill him And end his evil power over us. No, Enkidu cried; it is the journey That will take away our life. Don’t be afraid, said Gilgamesh. We are together. There is nothing We should fear. Standing Still When the king tells the Elders of Uruk that he intends to slay Humbaba, a curious interaction takes place Gilgamesh justifies his actions by insisting that “the youth of Uruk need this fight,” and the old men flush with memories of glories from long ago; they agree to his plan We are reminded, once again, of the stagnation that has taken place here; these Elders are no longer fighters, and the fighters grow restless from lack of fighting Revitalization by Proxy Yet none of the youth of Uruk fight with him; how can he argue that they need the fight? We see here the idea of revitalization by proxy – we saw this earlier when Enkidu first battled Gilgamesh, with the citizenry of Uruk erupting in cheers when their king’s equal proved his worth Gilgamesh goes out to overcome the monster, and the book does an oddly effective job of positioning it within the archetypal context of saving a province or nation; his victory is the City’s, for victory brings them life they otherwise miss Do we need enemies? Would we stagnate without conflict? He tried to ask his friend for help Whom he had just encouraged to move on, But he could only stutter and hold out His paralyzed hand. It will pass, said Gilgamesh. Would you want to stay behind because of that? We must go down into the forest together. Forget your fear of death. I will go before you And protect you. Let the Battle Begin Gilgamesh and Enkidu depart with Ninsun’s blessing and prayers, and the two men draw near Humbaba’s realm When they reach his gate, Enkidu is wounded, his hand crippled by the barrier’s supernatural powers; Gilgamesh dismisses his wound, although he later has a dream that indicates that only one of them will return to Uruk The dream plays itself in real life, as Humbaba wounds Enkidu badly in his initial attack; Gilgamesh stands paralyzed, and while he eventually decapitates the creature of nightmares, it is only through Enkidu’s daring slash that Humbaba is brought down A Goddess Scorned The epic spares no time in moving from triumph to tragedy; no sooner have Gilgamesh and Enkidu defeated Humbaba than Ishtar appears Gilgamesh’s dealings with her result in the Bull of Heaven’s attack, which quickly kills three hundred men before Enkidu strikes it down One could reasonably question whether Gilgamesh’s candor is wise here; if he knows Ishtar’s ways well enough, he should expect retribution for his words Ishtar’s Purpose Ishtar appears without preamble, although it’s worth noting that she has a larger role in the entire epic than in Mason’s verse narrative She is the goddess of love and war, and the seeming contradiction in those roles merely serves to highlight the violence at the heart of powerful love Know Your Enemy Why is Gilgamesh so resistant to her? He knows her history - one of betrayal and pain – and alludes to it in the crudest way possible Those who love her know only grief in the end, because she turns on those she grows satisfied with Gilgamesh points out that it's naive to assume that a goddess could love a mortal After all, he's part god, and that alone has been enough to separate him from the mortal world Reaping What They Sowed At any rate, Gilgamesh defies her, Ishtar unleashes her punishment, and Enkidu must save his friend yet again This is their final offense in the gods’ eyes; they’ve killed two beings who were of great use to the divine, and one of them must die Watch What You Do This strikes us as a betrayal, both because Gilgamesh didn’t exactly request to be visited by the Bull of Heaven and because his initial desire to kill Humbaba is not entirely his own (we learn through Ninsun’s prayers that Shamash, the Sun God and Ishtar’s husband/brother, has sent Gilgamesh to do his bidding) How can they be punished with death for serving the dictates of the gods? Or is it that they dared to resist the fates that divinities set up for them? Should We Trust Them? This section of the epic argues that the larger powers at work in our lives – the ones responsible for birth, fate, and death – are flawed or irrational We’re introduced, in quick succession, to plenty of examples of the gods’ untrustworthiness and abuse Beyond the aforementioned “order” to kill Humbaba from Shamash, we see that Humbaba is the gods’ slave, the Bull of Heaven kills innocent men while under Ishtar’s influence, and the gods argue (morbidly) over whether Enkidu or Gilgamesh should be killed Rebel Yell In many ways, this section provides more ammunition for the camp that sees Gilgamesh as a “rebellion” rather than a chronicle We see the tension humans felt while regarding the divine, the joy of knowing life given by gods, the agony of seeing that life taken away by the same deities, and the anger that results from not understanding the greater meaning of the bigger picture (why do the good die?) Everything feels capricious and arbitrary…and we know how poorly humans deal with dysfunctional order A man sees death in things. That is what it is to be a man. You’ll know When you have lost the strength to see The way you once did. You’ll be alone and wander Looking for that life that’s gone, or some Eternal life you have to find. In His Hands But Gilgamesh proves unable to resist the demands of the gods in the end; he can find no words with which to convince them to reverse their decision, can perform no feat of strength to prevent them from carrying out their will Enkidu dies not from fighting the Bull of Heaven, but from the wound he suffered while battling Humbaba as Gilgamesh stood paralyzed – a wound that resulted from his prior crippling at Humbaba’s gate, a crippling that Gilgamesh trivialized at the time He’s reduced to weeping helplessly as his friend slowly expires, leaving him utterly alone again, alone with his sorrow…and his guilt Why am I to die, You to wander on alone? Is that the way it is with friends? Outward Bound At this point, Gilgamesh begins to revert to his old ways – fixated only on one thing, he grows maniacal in his desire to relieve himself of pain Once burned, twice shy This three-page section immediately following Enkidu’s passing is one of my favorites in the epic; it has some truly profound things to say about grief, why we grieve, and how we recover He Who Survives Gilgamesh eventually travels through the desert – the literal and metaphorical one – in search of Utnapishtim The book refers to him as “the one who survived the flood” Here we see another parallel with a Biblical archetype Before, we had Enkidu cast out of Eden Here, we have a flood – sent by Ishtar – that wipes out virtually everything, save Utnapishtim and one of each animal he could save The Tin Man… What Gilgamesh discovers during his journey will ultimately determine whether he will be successful – whether he will recover from pain or drown in it Whether he succeeds, of course, is a lesson for another day…