Document

advertisement

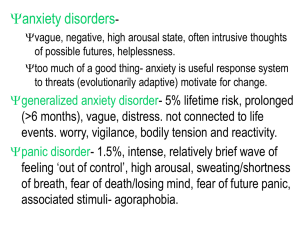

Abnormal Psychology Fifth Edition Oltmanns and Emery PowerPoint Presentations Prepared by: Cynthia K. Shinabarger Reed This multimedia product and its contents are protected under copyright law. The following are prohibited by law: any public performance or display, including transmission of any image over a network; preparation of any derivative work, including the extraction, in whole or in part, of any images; any rental, lease, or lending of the program. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Chapter Six Anxiety Disorders Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Chapter Outline • Symptoms • Diagnosis • Frequency • Causes • Treatment Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Overview • Taken together, the various forms of anxiety disorders—including phobias, obsessions, compulsions, and extreme worry—represent the most common type of abnormal behavior. • Anxiety disorders share several important similarities with mood disorders. • From a descriptive point of view, both categories are defined in terms of negative emotional responses. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Overview • Stressful life events seem to play a role in the onset of both depression and anxiety. • Cognitive factors are also important in both types of problems. • From a biological point of view, certain brain regions and a number of neurotransmitters are involved in the etiology of anxiety disorders as well as mood disorders. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Symptoms • People with anxiety disorders share a preoccupation with, or persistent avoidance of, thoughts or situations that provoke fear or anxiety. • Anxiety disorders frequently have a negative impact on various aspects of a person’s life. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Symptoms Anxiety • Anxious mood is often defined in contrast to the specific emotion of fear, which is more easily understood. • Fear is experienced in the face of real, immediate danger. • In contrast to fear, anxiety involves a more general or diffuse emotional reaction—beyond simple fear—that is out of proportion to threats from the environment. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Symptoms Anxiety (continued) • Rather than being directed toward the person’s present circumstances, anxiety is associated with the anticipation of future problems. • Anxiety can be adaptive at low levels, because it serves as a signal that the person must prepare for an upcoming event. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Symptoms Anxiety (continued) • A pervasively anxious mood is often associated with pessimistic thoughts and feelings. • The person’s attention turns inward, focusing on negative emotions and selfevaluation rather than on the organization or rehearsal of adaptive responses that might be useful in coping with negative events. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Symptoms Excessive Worry • Worrying is a cognitive activity that is associated with anxiety. • Worry can be defined as a relatively uncontrollable sequence of negative, emotional thoughts that are concerned with possible future threats or danger. • Worriers are preoccupied with “self-talk” rather than unpleasant visual images. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Symptoms Excessive Worry (continued) • The distinction between pathological and normal worry hinges on quantity—how often the person worries and about how many different topics the person worries. • It also depends on the quality of worrisome thought. • Excessive worriers are more likely than other people to report that the content of their thoughts is negative, that they have less control over the content and direction of their thoughts, and that in comparison to other adults, their worries are less realistic. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Symptoms Panic Attacks • A panic attack is a sudden, overwhelming experience of terror or fright. • Whereas anxiety involves a blend of several negative emotions, panic is more focused. • Some clinicians think of panic as a normal fear response that is triggered at an inappropriate time. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Symptoms Panic Attacks (continued) • Descriptively, panic can be distinguished from anxiety in two other respects: It is more intense, and it has a sudden onset. • Panic attacks are defined largely in terms of a list of somatic or physical sensations, ranging from heart palpitations, sweating, and trembling to nausea, dizziness, and chills. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Symptoms Panic Attacks (continued) • People undergoing a panic attack also report a number of cognitive symptoms. • They may feel as though they are about to die, lose control, or go crazy. • Some clinicians believe that the misinterpretation of bodily sensations lies at the core of panic disorder. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Symptoms Panic Attacks (continued) • Panic attacks are further described in terms of the situations in which they occur, as well as the person’s expectations about their occurrence. • An attack is said to be expected, or cued, if it occurs only in the presence of a particular stimulus. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Symptoms Phobias • Phobias are persistent, irrational, narrowly defined fears that are associated with a specific object or situation. • A fear is not considered phobic unless the person avoids contact with the source of the fear or experiences intense anxiety in the presence of the stimulus. • Phobias are also irrational or unreasonable. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Symptoms Phobias (continued) • The most straightforward type of phobia involves fear of specific objects or situations. • Some people experience marked fear when they are forced to engage in certain activities, such as public speaking, initiating a conversation, eating in restaurants, or using public rest rooms, which might involve being observed or evaluated by other people. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Symptoms Phobias (continued) • The most complex and incapacitating form of phobic disorder is agoraphobia, which literally means “fear of the marketplace (or places of assembly)” and is usually described as fear of public spaces. • People with agoraphobia are frequently afraid that they will experience an “attack” of symptoms that will be either incapacitating or embarrassing, and that help will not be available to them. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Symptoms Obsessions and Compulsions • Obsessions are repetitive, unwanted, intrusive cognitive events that may take the form of thoughts or images or impulses. • They intrude suddenly into consciousness and lead to an increase in subjective anxiety. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Symptoms Obsessions and Compulsions (continued) • Obsessive thinking can be distinguished from worry in two primary ways: 1) Obsessions are usually experienced as coming from “out of the blue,” whereas worries are often triggered by problems in everyday living; and 2) the content of obsessions most often involves themes that are perceived as being socially unacceptable or horrific, such as sex, violence, and disease/contamination, whereas the content of worries tends to center around more acceptable, commonplace concerns, such as money and work. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Symptoms Obsessions and Compulsions (continued) • Compulsions are repetitive behaviors or mental acts that are used to reduce anxiety. • In contrast to the obsessions described by people who are not in treatment, those experienced by clinical patients occur more frequently, last longer, and are associated with higher levels of discomfort than normal obsessions. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Symptoms Obsessions and Compulsions (continued) • Compulsions reduce anxiety, but they do not produce pleasure. • Thus some behaviors, such as gambling and drug use, that people describe as being “compulsive” are not considered true compulsions according to this definition. • The two most common forms of compulsive behavior are cleaning and checking. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Diagnosis Brief Historical Perspective • Anxiety and abnormal fears did not play a prominent role in the psychiatric classification systems that began to emerge in Europe during the second half of the nineteenth century. • People with anxiety problems seldom came to the attention of psychiatrists during the nineteenth century because very few cases of anxiety disorder require institutionalization. • Freud and his followers were responsible for some of the first extensive clinical descriptions of pathological anxiety states. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Diagnosis Brief Historical Perspective (continued) • Freud focused primarily on the importance of mental conflicts and innate biological impulses in the etiology of anxiety. • This perspective played a central role in the way that anxiety disorders were classified in early versions of the DSM. • They were grouped with several other types of problems under the general heading of neurosis, a term used to describe persistent emotional disturbances, such as anxiety and depression, in which the person is aware of the nature of the problem. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Diagnosis Brief Historical Perspective (continued) • The basic outline of Freud’s theory of anxiety hinges on the notion that the person’s ego can experience a small amount of anxiety as a signal indicating that an instinctual impulse that has previously been associated with punishment and disapproval is about to be acted on. • This usually means that the person is going to do something aggressive or sexual that is considered inappropriate. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Diagnosis Brief Historical Perspective (continued) • Signal anxiety triggers the use of ego defenses— primarily repression—that prevent conscious recognition of the forbidden impulse, inhibit its expression, and thereby reduce the person’s anxiety. • When the system works as it should, anxiety is adaptive, and the person’s behavior is regulated to conform with social expectations. • Unfortunately, people can still experience pathological levels of anxiety if the system is overwhelmed. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Diagnosis Contemporary Diagnostic Systems (DSM-IV-TR) • The DSM-IV-TR approach to classifying anxiety disorders is based primarily on descriptive features, rather than etiological hypotheses, and recognizes several specific subtypes. • They include panic disorder, three types of phobic disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder, as well as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and acute stress disorder. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Diagnosis Contemporary Diagnostic Systems (DSM-IV-TR) (continued) • To meet the diagnostic criteria for panic disorder, a person must experience recurrent, unexpected panic attacks. • Panic disorder is divided into two subtypes, depending on the presence or absence of agoraphobia. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Diagnosis Contemporary Diagnostic Systems (DSMIV-TR) (continued) • DSM-IV-TR defines agoraphobia in terms of anxiety about being in situations from which escape might be either difficult or embarrassing. • This approach is based on the view that agoraphobia is typically a complication that follows upon the experience of panic attacks. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Diagnosis Contemporary Diagnostic Systems (DSM-IV-TR) (continued) • A specific phobia is defined in DSMIV-TR as “a marked and persistent fear that is excessive or unreasonable, cued by the presence or anticipation of a specific object or situation.” • Frequently observed types of specific phobia include fear of heights, small animals, tunnels or bridges, storms, illness and injury, being in a closed place, and being on certain kinds of public transportation. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Diagnosis Contemporary Diagnostic Systems (DSM-IV-TR) (continued) • The DSM-IV-TR definition of social phobia is almost identical to that for specific phobia, but it includes the additional element of performance. • A person with a social phobia is afraid of (and avoids) social situations. • These situations fall into two broad headings: doing something in front of unfamiliar people (performance anxiety) and interpersonal interactions (such as dating and parties). • Fear of being humiliated or embarrassed presumably lies at the heart of the person’s discomfort. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Diagnosis Contemporary Diagnostic Systems (DSM-IV-TR) (continued) • Excessive anxiety and worry are the primary symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). • The person must have trouble controlling these worries, and the worries must lead to significant distress or impairment in occupational or social functioning. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Diagnosis Contemporary Diagnostic Systems (DSMIV-TR) (continued) • In order to distinguish GAD from other forms of anxiety disorder, DSM-IV-TR notes that the person’s worries should not be focused on having a panic attack (as in panic disorder), being embarrassed in public (as in social phobia), or being contaminated (as in obsessive–compulsive disorder). Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Diagnosis Contemporary Diagnostic Systems (DSM-IV-TR) (continued) • The person’s worries and free-floating anxiety must be accompanied by at least three of the following symptoms: 1) restlessness or feeling keyed up or on edge, 2) being easily fatigued, 3) difficulty concentrating or mind going blank, 4) irritability, 5) muscle tension, and 6) sleep disturbance. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Diagnosis Contemporary Diagnostic Systems (DSM-IV-TR) (continued) • DSM-IV-TR defines obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) in terms of the presence of either obsessions or compulsions. • Most people who meet the criteria for this disorder actually exhibit both of these symptoms. • The DSM-IV-TR definition requires that the person must attempt to ignore, suppress, or neutralize the unwanted thoughts or impulses. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Diagnosis “Lumpers” and “Splitters” • Experts who classify mental disorders can be described informally as belonging to one of two groups, “lumpers” and “splitters.” • Lumpers argue that anxiety is a generalized condition or set of symptoms without any special subdivisions. • Splitters distinguish among a number of conditions, each of which is presumed to have its own etiology. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Diagnosis Course and Outcome • Long-term follow-up studies focused on clinical populations indicate that many people continue to experience symptoms of anxiety and associated social and occupational impairment many years after their problems are initially recognized. • On the other hand, some people do recover completely. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Frequency Prevalence • The National Comorbidity Survey (NCS), which included approximately 8,000 people aged 15 to 54 throughout the United States, found that anxiety disorders are more common than any other form of mental disorder. • The same conclusion had been reached previously in the ECA study. • Specific phobias are the most common type of anxiety disorder, with a 1-year prevalence of about 9 percent of the adult population (men and women combined). Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Frequency Comorbidity • One study found that 50 percent of people who met the criteria for one anxiety disorder also met the criteria for at least one other form of anxiety disorder or mood disorder. • Both anxiety and depression are based on emotional distress, so it is not surprising that considerable overlap also exists between anxiety disorders and mood disorders. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Frequency Comorbidity (continued) • Approximately 60 percent of people who receive a primary diagnosis of major depression also qualify for a secondary diagnosis of some type of anxiety disorder. • People who have an anxiety disorder are about three times more likely to have an alcohol use disorder than are people without an anxiety disorder. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Frequency Gender Differences • Women are three times as likely as men to experience specific phobias. • Women are about twice as likely as men to experience panic disorder, agoraphobia (without panic disorder), and generalized anxiety disorder. • Social phobia is also more common among women than among men, but the difference is not as striking as it is for other types of phobia. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Frequency Gender Differences (continued) • The only type of anxiety disorder for which there does not appear to be a significant gender difference is OCD. • Among people who have anxiety disorder, relapse rates are also much higher for women than for men. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Frequency Anxiety Across the Life Span • Data from the ECA study indicate that the prevalence of anxiety disorders is lower among elderly men and women than it is among people in other age groups. • Most elderly people with an anxiety disorder have had the symptoms for many years. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Frequency Anxiety Across the Life Span (continued) • It is relatively unusual for a person to develop a new case of panic disorder, specific phobia, social phobia, or obsessive–compulsive disorder at an advanced age. • The only type of anxiety disorder that begins with any noticeable frequency in late life is agoraphobia. • The diagnosis of anxiety disorders among elderly people is complicated by the need to consider factors such as medical illnesses and other physical impairments and limitations. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Frequency Cross-Cultural Comparisons • People in Western societies often experience anxiety in relation to their work performance, whereas in other societies people may be more concerned with family issues or religious experiences. • Anxiety disorders have been observed in preliterate as well as Westernized cultures. • Of course, the same descriptive and diagnostic terms are not used in every culture, but the basic psychological phenomena appear to be similar. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Adaptive and Maladaptive Fears • Current theories regarding the causes of anxiety disorders often focus on the evolutionary significance of anxiety and fear. • These emotional response systems are clearly adaptive in many situations. • They mobilize responses that help the person survive in the face of both immediate dangers and long-range threats. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Adaptive and Maladaptive Fears (continued) • An evolutionary perspective helps to explain why human beings are vulnerable to anxiety disorders, which can be viewed as problems that arise in the regulation of these necessary response systems. • The important question is not why we experience anxiety, but why it occasionally becomes maladaptive. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Adaptive and Maladaptive Fears (continued) • Isaac Marks and Randolph Nesse suggest that generalized forms of anxiety probably evolved to help the person prepare for threats that could not be identified clearly. • More specific forms of anxiety and fear probably evolved to provide more effective responses to certain types of danger. • Each type of anxiety disorder can be viewed as the dysregulation of a mechanism that evolved to deal with a particular kind of danger. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Social Factors • Several investigations suggest that stressful life events can influence the onset of anxiety disorders as well as depression. • Patients with anxiety disorders are more likely than other people to report having experienced a negative event in the months preceding the initial development of their symptoms. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Social Factors (continued) • Why do some negative life events lead to depression while others lead to anxiety? • The nature of the event may be an important factor in determining the type of mental disorder that appears. • People who develop an anxiety disorder are much more likely to have experienced an event involving danger (lack of security), whereas people who are depressed are more likely to have experienced a severe loss (lack of hope). Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Social Factors (continued) • People who report parental neglect, abuse, and violence are more vulnerable to the development of both mood disorders and anxiety disorders. • Causal pathways are complex. • There does not seem to be a direct connection between particular forms of adverse environmental events and specific types of mental disorder. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Social Factors (continued) • Several studies have found that people with panic disorder and agoraphobia are more likely to report that they had problems associated with insecure attachment as children. • Attachment difficulties are not restricted to agoraphobia. • Studies indicate that they also set the stage for other types of anxiety in adults, including generalized anxiety disorder, and social phobia. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Psychological Factors • Since the 1920s, experimental psychologists working in laboratory settings have been interested in the possibility that specific fears might be learned through classical (or Pavlovian) conditioning. • Many intense, persistent, irrational fears seem to develop after the person has experienced a traumatic event. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Psychological Factors (continued) • Current views on the process by which fears are learned suggest that the process is guided by a module, or specialized circuit in the brain, that has been shaped by evolutionary pressures. • These modules are designed to operate at maximal speed, are activated automatically, and perform without conscious awareness. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Psychological Factors (continued) • Human beings seem to be prepared to develop intense, persistent fears only to a select set of objects or situations. • Many investigations have been conducted to test various facets of this preparedness model. • The results of these studies support many features of the theory. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Psychological Factors (continued) • Observational learning may also affect the development of intense fear, because some phobias develop in the absence of any direct experience with the feared object. • Learning experiences are clearly important in the origins of phobias, but their impact often depends on the existence of prepared associations between stimuli. • Furthermore, vicarious learning is often as important as direct experience. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Psychological Factors (continued) • Cognitive events play an important role as mediators between experience and response. • Perceptions, memory, and attention all influence the ways that we react to events in our environments. • It is now widely accepted that these cognitive factors play a crucial role in the development and maintenance of various types of anxiety disorders. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Psychological Factors (continued) • There is an important relationship between anxiety and the perception of control. • People who believe that they are able to control events in their environment are less likely to show symptoms of anxiety than are people who believe that they are helpless. • An extensive body of evidence supports the conclusion that people who believe that they are less able to control events in their environment are more likely to develop global forms of anxiety, as well as various specific types of anxiety disorder. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Psychological Factors (continued) • According to David Clark, panic disorder may be caused by the catastrophic misinterpretation of bodily sensations or perceived threat. • Anxious mood is accompanied by a narrowing of the person’s attentional focus and an increased awareness of bodily sensations. • The crucial stage comes next, when the person misinterprets the bodily sensation as a catastrophic event. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Psychological Factors (continued) • In recent years, several lines of research have converged to clarify the basic cognitive mechanisms involved in worry. • Experts now believe that attention plays a crucial role in the onset of this process. • People who are prone to excessive worrying are unusually sensitive to cues that signal the existence of future threats. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Psychological Factors (continued) • Once attention has been drawn to threatening cues, the performance of adaptive, problemsolving behaviors is disrupted, and the worrying cycle launches into a repetitive sequence in which the person rehearses anticipated events and searches for ways to avoid them. • Attentional mechanisms also seem to be involved in the etiology and maintenance of social phobias. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Psychological Factors (continued) • Worrying is unproductive and self-defeating in large part because it is associated with a focus on self-evaluation (fear of failure) and negative emotional responses rather than on external aspects of the problem and active coping behaviors. • We may be consciously aware of these processes and simultaneously be unable to inhibit them. • The struggle to control our thoughts often leads to a process known as thought suppression, an active attempt to stop thinking about something. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Psychological Factors (continued) • Recent evidence suggests that trying to rid one’s mind of a distressing or unwanted thought can have the unintended effect of making the thought more intrusive. • Thought suppression might actually increase, rather then decrease, the strong emotions associated with those thoughts. • Obsessive–compulsive disorder may be related, in part, to the maladaptive consequences of attempts to suppress unwanted or threatening thoughts that the person has learned to see as being dangerous or forbidden. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Biological Factors • Several pieces of evidence indicate that biological events play an important role in the development and maintenance of anxiety disorders. • Family studies indicate that the relatives of people with panic disorder show an elevated risk of panic disorder themselves but not an elevated risk of generalized anxiety disorder. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Biological Factors (continued) • The same pattern holds for the relatives of people with generalized anxiety disorder: The relatives exhibit a high rate of GAD but not a high rate of panic disorder. • This evidence is consistent with the proposition that panic disorder and GAD are, indeed, etiologically separate disorders. • A family study of social phobia has demonstrated that the generalized form of this disorder (where the person is fearful in most types of social situations) is also familial in nature and etiologically distinct from other types of anxiety disorder. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Biological Factors (continued) • Research results suggest that the nongeneralized form of social phobia is not influenced by genetic factors. • Data regarding obsessive–compulsive disorder suggest that a more general vulnerability to anxiety disorders is genetically transmitted through the family. • The results of the family studies all point toward the potential influence of genetic factors in anxiety disorders. • Most of the evidence also supports the validity of the DSM-IV-TR subtypes. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Biological Factors (continued) • Family studies do not prove the involvement of genes, because family members also share environmental factors (diet, culture, and so on). • Twin studies provide a more stringent test of the genetic hypothesis. • Kenneth Kendler, a psychiatrist at the Medical College of Virginia, and his colleagues have studied anxiety disorders in very large samples of male–male and female–female twin pairs. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Biological Factors (continued) • Their analyses have led them to several important conclusions: 1. Genetic risk factors for these disorders are neither highly specific (a different set of genes being associated with each disorder) nor highly nonspecific (one common set of genes causing vulnerability for all disorders). 2. Two genetic factors have been identified: one associated with GAD, panic disorder, and agoraphobia, and the other with specific phobias. 3. Environmental risk factors that would be unique to individuals also play an important role in the etiology of all anxiety disorders. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Biological Factors (continued) • Laboratory studies of fear conditioning in animals have identified specific pathways in the brain that are responsible for detecting and organizing a response to danger. • The amygdala plays a central role in these circuits, which represent the biological underpinnings of the evolved fear module that we discussed earlier in connection with classical conditioning of phobias. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Biological Factors (continued) • Studies with animals have shown that artificial stimulation of the amygdala can produce different effects, depending in large part on the environmental context in which the animal is stimulated. • Anger, disgust, and sexual arousal are all emotional states that are associated with activity in pathways connecting the thalamus, the amygdala, and their projections to other brain areas. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Biological Factors (continued) • The brain regions that have been identified in studies of fear conditioning seem to play an important role in both phobic disorders and panic disorder. • The locus ceruleus, a small area located in the brain stem, has also been the focus of considerable emphasis in research on panic disorder. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Biological Factors (continued) • Research with monkeys has demonstrated that the firing rate of neurons in the locus ceruleus increases dramatically when a monkey is frightened. • Furthermore, electrical stimulation of the locus ceruleus triggers a strong fear response that resembles a panic attack. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Biological Factors (continued) • The results of studies using brain imaging procedures with OCD patients do not overlap a great deal with findings for other types of anxiety disorder. • Obsessions and compulsions are associated with multiple brain regions, including the basal ganglia (a system that includes the caudate nucleus and the putamen), the orbital prefrontal cortex, and the anterior cingulate cortex. • These circuits are overly active in people with OCD, especially when the person is confronted with stimuli that provoke his or her obsessions. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Biological Factors (continued) • Pharmacological challenge procedures have played an important role in exploring the neurochemistry of panic disorder. • The logic behind this method is simple: If a particular brain mechanism is “challenged,” or stressed, by the artificial administration of chemicals, and if that procedure leads to the onset of a panic attack, then the neurochemical process that mediates that effect may also be responsible for panic attacks that take place outside the laboratory. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Biological Factors (continued) • Pharmacological challenge procedures were inspired by a few clinical studies, reported in the 1940s and 1950s, which noted that patients with “anxiety neurosis” sometimes experienced an increase in subjective anxiety following vigorous physical exercise. • This change in subjective symptoms appeared to be associated with an extremely rapid and excessive increase in lactic acid in the blood. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Biological Factors (continued) • A large number of studies have demonstrated that lactate infusions can provoke panic attacks in anywhere from 50 to 90 percent of patients with anxiety or panic disorders, as compared to only 0 to 25 percent of normal control subjects. • Many other procedures have been found to induce panic in the laboratory. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Causes Biological Factors (continued) • These include the infusion of different chemicals, such as caffeine, as well as the inhalation of air enriched with carbon dioxide. • Various pharmacological challenge studies have suggested the influence of serotonin, norepinephrine, GABA, and dopamine in the production of panic attacks. • The general finding appears to be that several neurotransmitter systems are involved in the etiology of panic disorder. • This conclusion also applies to other forms of anxiety disorder, such as GAD and social phobia. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Treatment Psychological Interventions • Like psychoanalysis, behavior therapy was initially developed for the purpose of treating anxiety disorders, especially specific phobias. • The first widely adopted procedure was systematic desensitization. • In the years since systematic desensitization was originally proposed, many different variations on this procedure have been employed. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Treatment Psychological Interventions (continued) • The crucial feature of the treatment involves systematic maintained exposure to the feared stimulus. • Positive outcomes have been reported, regardless of the specific manner in which exposure is accomplished. • The treatment of panic disorder often includes two specific forms of exposure. • One, situational exposure, is used to treat agoraphobic avoidance. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Treatment Psychological Interventions (continued) • In this procedure, the person repeatedly confronts the situations that have previously been avoided. • Interoceptive exposure, the other form of exposure, is aimed at reducing the person’s fear of internal, bodily sensations that are frequently associated with the onset of a panic attack, such as increased heart and respiration rate and dizziness. • The process is accomplished by having the person engage in standardized exercises that are known to produce such physical sensations. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Treatment Psychological Interventions (continued) • The most effective form of psychological treatment for obsessive–compulsive disorder combines prolonged exposure to the situation that increases the person’s anxiety with prevention of the person’s typical compulsive response. • Behavior therapists have used relaxation procedures for many years. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Treatment Psychological Interventions (continued) • Relaxation training usually involves teaching the client alternately to tense and relax specific muscle groups while breathing slowly and deeply. • Outcome studies indicate that relaxation is a useful form of treatment for generalized anxiety disorder. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Treatment Psychological Interventions (continued) • Breathing retraining is a procedure that involves education about the physiological effects of hyperventilation and practice in slow breathing techniques. • It is often incorporated in treatments used for panic disorder. • Some clinicians believe that the process works by enhancing relaxation or increasing the person’s perception of control. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Treatment Psychological Interventions (continued) • Cognitive therapy is used extensively in the treatment of anxiety disorders. • Therapists help clients identify cognitions that are relevant to their problem; recognize the relation between these thoughts and maladaptive emotional responses (such as prolonged anxiety); examine the evidence that supports or contradicts these beliefs; and teach clients more useful ways of interpreting events in their environment. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Treatment Psychological Interventions (continued) • In the case of anxiety disorders, cognitive therapy is usually accompanied by additional behavior therapy procedures. • Several controlled outcome studies attest to the efficacy of cognitive therapy in the treatment of various types of anxiety disorder, including panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Treatment Biological Interventions • Medication is the most effective and most commonly used biological approach to the treatment of anxiety disorders. • The most frequently used types of minor tranquilizers are from the class of drugs known as benzodiazepines. • These drugs reduce many symptoms of anxiety, especially vigilance and subjective somatic sensations, such as increased muscle tension, palpitations, increased perspiration, and gastrointestinal distress. • They have relatively less effect on a person’s tendency toward worry and rumination. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Treatment Biological Interventions (continued) • Benzodiazepines have been shown to be effective in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorders and social phobias. • Many patients with panic disorder and agoraphobia relapse if they discontinue taking medication. • Common side effects of benzodiazepines include sedation accompanied by mild psychomotor and cognitive impairments. • The most serious adverse effect of benzodiazepines is their potential for addiction. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Treatment Biological Interventions (continued) • Another class of anti-anxiety medication, known as the azapirones, includes drugs that work on entirely different neural pathways than the benzodiazepines. • The only azapirone in clinical use is known as buspirone (BuSpar). • Some clinicians believe that buspirone is preferable to the benzodiazepines because it does not cause drowsiness and does not interact with the effects of alcohol. • The disadvantage is that patients do not experience relief from severe anxiety symptoms as quickly with buspirone as they do with benzodiazepines. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Treatment Biological Interventions (continued) • The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have become the preferred form of medication for treating almost all forms of anxiety disorder. • Reviews of controlled outcome studies indicate that they are at least as effective as other, more traditional forms of antidepressants in reducing symptoms of various anxiety disorders. • They also have fewer unpleasant side effects, they are safer to use, and withdrawal reactions are less prominent when they are discontinued. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Treatment Biological Interventions (continued) • Imipramine (Tofranil), a tricyclic antidepressant medication, has been used for more than 40 years in the treatment of patients with panic disorder. • Psychiatrists often prefer imipramine to anti-anxiety drugs for the treatment of panic disorder because patients are less likely to become dependent on the drug than they are to high-potency benzodiazepines like alprazolam. • The tricyclic antidepressants are used less frequently than the SSRIs because they produce several unpleasant side effects, including weight gain, dry mouth, and over-stimulation (sometimes referred to as an “amphetamine-like” response). Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Treatment Biological Interventions (continued) • Clomipramine (Anafranil), another tricyclic antidepressant, has been used extensively in treating obsessive–compulsive disorder. • Patients who continue to take the drug maintain the improvement, but relapse is common if medication is discontinued. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Treatment Biological Interventions (continued) • In actual practice, anxiety disorders are often treated with a combination of psychological and biological procedures. • Current evidence suggests that patients who receive both medication and psychotherapy may do better in the short run, but patients who receive only cognitive behavior therapy may do better in the long run because of difficulties that can be encountered when medication is discontinued. Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007 Copyright © Prentice Hall 2007