the exercise of judicial review: federalism and economic

advertisement

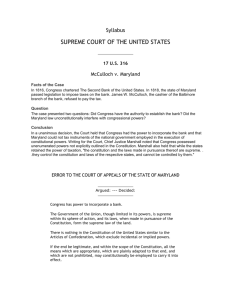

THE EXERCISE OF JUDICIAL REVIEW: FEDERALISM AND ECONOMIC REGULATION Topic #16 How Would Judicial Review be Used by the Supreme Court? • In the beginning, there were no precedents and all constitutional ambiguities remained open. • Marbury v. Madison established the precedent that the Supreme Court would play a leading role in resolving these ambiguities by exercising its power of judicial review. • What kind of cases would you expect to come before the Supreme Court in the first decades of the U.S. government? [Study Guide Q1] Three Historical Periods of SC Activism • 1820 – 1850: – Focus: The division of governmental powers -- specifically the boundaries between delegated powers of the federal government and the reserved powers of the state governments. – Decisions: The court generally interpreted the Constitution in ways favorable to the powers of the federal government. • 1875 – 1935 – Focus: The power of government at either the state or federal level to regulate economic life. – Decisions: The Court generally restricted the economic powers of both the federal and state governments, in effect incorporating the economic doctrine of "laissez-faire" into the Constitution. • 1940 -- present – Focus: Civil rights and liberties, i.e., the status of racial minorities (in particular African-Americans in the “Jim Crow” South) and the non-economic rights of individuals versus the authority of government at any level. – Decisions: Mixed, but generally more favorable to minorities and individual rights than in earlier periods. The Necessary and Proper Clause • The enumerated powers of Congress: • Article I, Section 8: – – – – – The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States; but all duties, imposts and excises shall be uniform throughout the United States; to borrow money on the credit of the United States; to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes; [plus 14 other enumerated powers] to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the government of the United States, or in any department or officer thereof. • Is this Necessary and Proper Clause a grant of additional powers to Congress, or a limitation on the powers enumerated just above? McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) • In exercising its enumerated powers, Congress will routinely authorizes the building of army forts, navy yards, post offices, federal court buildings, etc., that will be located within the boundaries of states. • Can states then impose taxes or regulations on such federal facilities? – Congress charted a Bank of the United States. – It had a branch in Baltimore (McCulloch was its manager). – Maryland imposed a tax all banks in the state not chartered by the state, including this branch of the U.S. Bank. – McCulloch refused to pay the tax, on the grounds that Maryland was intruding on the delegated powers of Congress. – McCulloch lost in state courts (Maryland v. McCulloch). – McCulloch appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, on the grounds that the case raised a question about the powers of the federal government. McCulloch v. Maryland (cont.) • Marshall was still Chief Justice and remained the Court’s dominant member. • The Court reversed the decision of the state court. • Marshall wrote the opinion, saying the case raised two issues. – Question 1: Did Congress have the power to incorporate a bank in the first place? • Incorporating banks is not an explicitly enumerated power of Congress. • And if the bank was not legitimately incorporated, it could hardly claim constitutional protection from state taxes. – Question 2: If Congress does has such a power, does Maryland nevertheless have the power to tax such a bank? McCulloch v. Maryland (cont.) • Answer to Question 1: – Yes, Congress has implied powers to choose among a variety of means to exercise its enumerated powers. – This government is acknowledged by all to be one of enumerated powers. . . . Among the enumerated powers, we do not find that of establishing a bank or creating a corporation. But there is no phrase in the instrument which, like the articles of confederation, excludes incidental or implied powers; and which requires that everything granted shall be expressly and minutely described. A constitution, to contain an accurate detail of all the subdivisions of which its great powers will admit, and of all the means by which they may be carried into execution, would partake of the prolixity of a legal code, and could scarcely be embraced by the human mind. Its nature, therefore, requires, that only its great outlines should be marked, its important objects designated, and the minor ingredients which compose those objects be deduced from the nature of the objects themselves. . . . In considering this question, then, we must never forget that it is a constitution we are expounding. McCulloch v. Maryland (cont.) – Although, among the enumerated powers of government, we do not find the word "bank," or "incorporation," we find the great powers to lay and collect taxes; to borrow money; to regulate commerce; to declare and conduct a war; and to raise and support armies and navies. The sword and the purse, all the external relations, and no inconsiderable portion of the industry of the nation, are entrusted to its government. It can never be pretended that these vast powers draw after them others of inferior importance, merely because they are inferior. Such an idea can never be advanced. But it may with great reason be contended, that a government, entrusted with such ample powers, on the due execution of which the happiness and prosperity of the nation so vitally depends, must also be entrusted with ample means for their execution. McCulloch v. Maryland (cont.) – But the constitution of the United States has not left the right of Congress to employ the necessary means, for the execution of the powers conferred on the government, to general reasoning. To its enumeration of powers is added that of making "all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this constitution, in the government of the United States, or in any department thereof." – We admit, as all must admit, that the powers of the government are limited, and that its limits are not to be transcended. But we think the sound construction of the constitution must allow to the national legislature that discretion, with respect to the means by which the powers it confers are to be carried into execution, which will enable that body to perform the high duties assigned to it, in the manner most beneficial to the people. Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the constitution, are constitutional. . . . McCulloch v. Maryland (cont.) • Answer to Question 2 – The power to tax is concurrent (shared by states and federal governments). – This great principle is, that the constitution and the laws made in pursuance thereof are supreme [by virtue of the Supremacy Clause]; that they control the constitution and laws of the respective States, and cannot be controlled by them. From this, which may be almost termed an axiom, other propositions are deduced as corollaries. . . . These are, 1st. that a power to create implies a power to preserve. 2nd. That a power to destroy, if wielded by a different hand, is hostile to, and incompatible with these powers to create and to preserve. 3d. That where this repugnancy exists, that authority which is supreme must control, not yield to that over which it is supreme. . . . – That the power to tax involves the power to destroy; that the power to destroy may defeat and render useless the power to create; that there is a plain repugnance, in conferring on one government a power to control the constitutional measures of another, which other, with respect to those very measures, is declared to be supreme over that which exerts the control, are propositions not to be denied. • Similar implications for the power of the federal government to tax entities created by state governments. Gibbons v. Ogden (1823) • The Interstate Commerce Clause: – The Congress shall have the power . . . to regulate commerce . . . among the several states. . . . • Ogden had a exclusive license issued by the state of New York to operate a steamboat in certain navigable waters of New York [on the Hudson River]. • Congress had passed a law for the licensing of vessels operating in the navigable waters of the U.S. – Gibbons had such federal license and went into competition with Ogden. – Ogden went into state court (Ogden v. Gibbons) and got an injunction against Gibbons. – Gibbons appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Gibbons v. Ogden (cont.) • The SC reversed the state courts. • Marshall again wrote the opinion of the Court. – Commerce, undoubtedly, is traffic, but it is something more - it describes the commercial intercourse between nations, and parts of nations, in all its branches, and is regulated by prescribing rules for carrying on that intercourse. . . . If commerce does not include navigation, the government of the Union has no direct power over that subject . . . . Yet this power has been exercised from the commencement of the government, has been exercised with the consent of all, and. has been understood by all to be a commercial regulation. All America understands, and has uniformly understood, the word commerce to comprehend navigation. – The subject to which the power is next applied is to commerce among the several states. The word among means intermingled with. . . . Commerce among the states cannot stop at the external boundary line of each state, but may be introduced into the interior. – [Only] the completely internal commerce of a state, then, may be considered as reserved for the state itself. Gibbons v. Ogden (cont.) • • • • The power of Congress, then, whatever it may be, must be exercised within the territorial jurisdiction of the several states. What is this power? It is the power to regulate, that is, to prescribe the rule by which commerce is to be governed. This power, like all others vested in Congress, is complete in itself, may be exercised to its utmost extent, and acknowledges no limitations other than are prescribed in the Constitution. . . . As the sovereignty of Congress, though limited to specified objects, is plenary as to those objects, the power over commerce with foreign nations and among the several states is vested in Congress as absolutely as it would be in a single [i.e., unitary] government, having in its constitution the same restrictions on the exercise of the power as are found in the Constitution of the United States. In argument, however, it has been contended that, if a law passed by a state in the exercise of its acknowledged sovereignty comes into conflict with a law passed by Congress in pursuance of the Constitution, they affect the subject and each other like equal opposing powers. But the framers of our Constitution foresaw this state of things and provided for it by declaring the supremacy not only of itself but of the laws made in pursuance of it. The nullity of any act inconsistent with the Constitution is produced by the declaration that the Constitution is supreme law. . . . In every such case, the act of Congress [made in pursuance of the Constitution] is supreme; and the law of the state must yield to it. Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918) • In this era, the SC generally interpreted the Constitution so as to restrict the economic powers of both the federal and state governments, in effect incorporating the economic doctrine of laissez-faire into the Constitution. – The U.S. economy had shift from largely agricultural to largely industrial. – Congress had previously enacted laws to prohibit or limit the use of child labor in interstate commerce. – The SC had previously ruled such laws unconstitutional, on the grounds that what happened in fields, mines, and factories is not part of commerce (or, in any case, of interstate commerce). – Congress then passed a law that prohibited the sale of goods produced by child labor in interstate commerce. • The SC had previously upheld the power of Congress to limit or even prohibit the sale in interstate commerce of such products as explosives, poisons, dangerous drugs, etc. – The constitutionality of this law was at stake in Hammer v. Dagenhart. Hammer v. Dagenhart (cont.) • The SC declared this law unconstitutional. – The controlling question for decision is: Is it within the authority of Congress in regulating commerce among the States to prohibit the transportation in interstate commerce of manufactured goods, the product of a factory in which children have been employed or permitted to work. – In Gibbons v. Ogden, Chief Justice Marshall that the commerce power “is the power to regulate; that is, to prescribe the rule by which commerce is to be governed." In other words, the power is one to control the means by which commerce is carried on, which is directly the contrary of the assumed right to forbid commerce from moving and thus destroy it as to particular commodities. But it is insisted that adjudged cases in this court establish the doctrine that the power to regulate given to Congress incidentally includes the authority to prohibit the movement of ordinary commodities and therefore that the subject is not open for discussion. The cases demonstrate the contrary. They rest upon the character of the particular subjects dealt with and the fact that the scope of governmental authority, state or national, possessed over them is such that the authority to prohibit is as to them but the exertion of the power to regulate. • Hammer v. Dagenhart was an example of “conservative activist” judges at work. The Great Depression and the New Deal • The 1929 stock market crash led to the Great Depression: – GDP approximately cut in half – 25% unemployment, etc. • Election of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal program: – Far greater federal intervention in the economy than ever previously attempted. – This put New Deal on a collision course with the Supreme Court. • No SC vacancies occurred in the first five years of FDR’s presidency, – perhaps in part due to strategic non-retirement. – By 1935, cases challenging the constitutionality of New Deal laws began to reach the SC, which began to invalidate a number of New Deal laws. “Court Packing” and the “Switch in Time” • In 1936, FDR was re-elected by a massive majority. – FDR was embolden to put forward [what his opponents called] the “Court Packing Plan.” • The plan was very controversial in Congress in elsewhere. • In West Coast Hotel v. Parrish (1937), the SC unexpectedly upheld the constitutionality of the new federal minimum wage law. – Justice Owen Roberts switched sides. – The “switch in time that saved nine [justices on the SC]” – Conservative justices began to retire. • Since then SC has essentially said that Congress’s power to regulate the economy will not be limited by judicial review (i.e., almost total judicial self-restraint with respect to economic issues), – though it has issued a few warning barks to Congress in recent years and may do more in the near future.