PSYCH ∙ Ms. Wiley ∙ Goodall's Naturalistic Observation, D___ Name

PSYCH ∙ Ms. Wiley ∙ Goodall’s Naturalistic Observation, D___ Name:

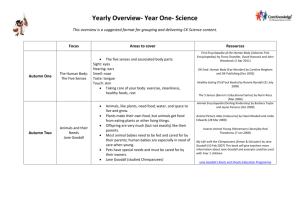

One of the most famous examples of a naturalistic observation is Jane Goodall’s work studying the behavior of chimpanzees. Through detailed observations, Jane Goodall revolutionized our knowledge of chimpanzee behavior.

Fifty years ago, a slender young Englishwoman was walking through a rainforest reserve in

Tanzania when she came across a dark figure hunched over a termite nest. A large male chimpanzee was foraging for food. So she stopped and watched the animal through her binoculars as he carefully took a twig, bent it, stripped it of its leaves, and finally stuck it into the nest. Then he began to spoon termites into his mouth. Thus Jane Goodall made one of the most important scientific observations of modern times in that remote African rainforest. She witnessed a creature, other than a human, in the act not just of using a tool but of making one. "It was hard for me to believe," she recalls. "At that time, it was thought that humans, and only humans, used and made tools. I had been told from school onwards that the best definition of a human being was man the toolmaker – yet I had just watched a chimp tool-maker in action. I remember that day as vividly as if it was yesterday."

Goodall telegraphed her boss with the news. His response has since become the stuff of scientific legend: "Now we must redefine man, redefine tools, or accept chimpanzees as humans." As the distinguished Harvard paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould put it, this was "one of the great achievements of 20th-century scholarship.” Goodall's subsequent observations found that not only did the chimpanzee make and use tools but that our nearest evolutionary cousins embraced, hugged, and kissed each other. They experienced adolescence, developed powerful mother-and-child bonds, and used political chicanery (trickery) to get what they wanted. They also made war, wiping out members of their own species with almost genocidal brutality on one occasion that was observed by Goodall.

This work has held up a mirror, albeit a blurred one, to our own species, suggesting that a great many of our behaviors, once thought to be uniquely human, may have been inherited from the common ancestors that Homo sapiens shared with chimpanzees six million years ago. We therefore have much to commemorate 50 years after Goodall began her strolls through Gombe. These celebrations began yesterday at the Berlin film festival with the premiere of Lorenz Knauer's documentary about Goodall, Jane's Journey – which includes a walk-on part for Angelina Jolie – and will continue throughout the year.

Now aged 76, Goodall exudes a calm confidence as she travels the world, promoting green causes established by the Jane Goodall

Institute, which she set up in 1977 in order to promote research and protect chimpanzees and their habitats. But in 1960, she looked an unlikely scientific pioneer. Goodall had no academic training, having grown up in middle-class gentility in the postwar years, a time when women were expected to be wives and little else. However, she burned with two passions: a love of animals and a love of

Africa. "I got my love of animals from the Dr. Dolittle books and my love of Africa from the Tarzan novels," she says.

A friend took a job in Kenya, and Goodall decided to join her, working as a waitress to raise funds for her trip. In Nairobi, Goodall was introduced to Louis Leakey, the scientist whose fossil discoveries had finally proved mankind's roots were African, not Asian, as had previously been supposed. At this time, Leakey was looking for someone to study chimpanzees in the wild and to find evidence of shared ancestry between humans and the great apes. Previous studies of primates had been confined to captive animals but Leakey believed, presciently, that much more could be learned by studying them in the wild. More to the point, Goodall would make a perfect observer, he believed, coming – as she did – "with a mind uncluttered and unbiased by theory", a point that is acknowledged by Goodall.

"I remember my first day, looking up from the shore to the forest, hearing the apes and the birds, and smelling the plants, and thinking this is very, very unreal," she says. "Then I started walking through the forest and as soon as a chimp saw me, it would run away." After a few weeks one male, who she named David Greybeard because of his white-tufted chin, let her approach him – tempted by the odd banana – and allowed her to observe him as he foraged for food. (It was David Greybeard who Goodall later watched making that leafy tool to obtain termites.) More and more troop members followed suit and Goodall was eventually allowed to observe their behavior almost as if she was a chimpanzee herself.

Slowly she built up a picture of chimp life in all its domestic detail: the grooming, the foodsharing, the status wrangles, and the fights. Goodall gave her chimps names – David

Greybeard, Flint, Goliath, Passion, Frodo and Fifi – much to the irritation of academics. At this time scientists were particularly sensitive about giving human attributes to animals.

Anthropomorphism was simply not on, they told Goodall when, in the early 60s, she took a

PhD at Cambridge at the insistence of Leakey – who was desperate for his protégé to gain

academic respectability. "These people were trying to make ethology a hard science," Goodall recalls. "So they objected – quite unpleasantly – to me naming my subjects and for suggesting that they had personalities, minds and feelings. I didn't care. I didn't want to become a professor or get tenure or teach or anything. All I wanted to do was get a degree because Louis Leakey said I needed one, which was right, and once I succeeded I could get back to the field."

In any case, Goodall (who got her PhD in 1965) believes it is simple nonsense to say that animals, particularly chimpanzees which are so closely related to humans, do not have personalities. "You cannot share your life with a dog, as I had done in Bournemouth, or a cat, and not know perfectly well that animals have personalities and minds and feelings. You know it and I think every single one of those scientists knew it too but because they couldn't prove it, they wouldn't talk about it.

But I did talk about it.”

The presence of lots of chimpanzee mothers had a considerable influence on the way Goodall raised her son. "There are certain characteristics that define a good chimp mother," she says. "She is patient, she is protective but she is not over-protective – that is really important. She is tolerant but she can impose discipline. She is affectionate. She plays. And the most important of all: she is supportive. So that if her kid gets into a fight, even if it is with a higher-ranking individual, she will not hesitate to go in and help."

Goodall contrasts the behavior of Flo, a good mother, with that of Passion, a poor one: "It was a common sight to see Passion walking along followed by a whimpering infant who was frantically trying to catch up and climb aboard her for transport," Goodall records in her book In the Shadow of Man. By contrast, Flo's child Fifi was a noticeably confident adolescent, Goodall states, "her relaxed behavior with her elders stemming from the fact that she enjoyed a particularly friendly relationship with her mother".

Goodall found that the parallels between Homo sapiens and chimpanzees are, generally speaking, deep and numerous. Yet there are the crucial differences that divide our species. "The most important one is straightforward," says Goodall. "We have language and they do not. Chimps communicate by embracing, patting, looking – all these things. And they have lots of sounds. But they cannot sit and discuss. They cannot teach about things that are not present, as far as we know." And this takes us to the heart of Goodall's discoveries about the nature of the chimpanzee and its implications for our understanding of our nature. Language and discussion develop the intellect, she argues. "The brain of a chimp and the brain of a human are not that different anatomically. But we started to talk to each other and that drove the brain – because there were more and more things that we could do with it.”

Clearly, we have learned a great deal not just about our evolutionary cousins but about ourselves thanks to the work that Goodall began in Tanzania. The tragedy is that many of these programs are now threatened by the current catastrophic decline in population of the chimpanzee across Africa. One hundred years ago, there were two million of them. Today there are less than 200,000, with habitat destruction and bushmeat trade being responsible for the loss of increasing numbers. The implications for science and for our understanding of ourselves are profound, as Stephen Jay Gould makes clear in his introduction to the revised edition of

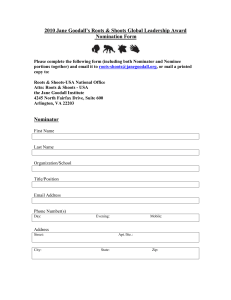

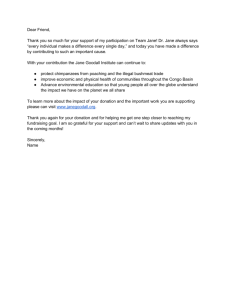

Goodall's In the Shadow of Man. "We can never know, by studying ourselves alone, whether important aspects of our mental capacities reflect an ancestral evolutionary heritage or new features evolved or socially acquired by our lineage. Chimpanzees are the best natural experiment we will ever have for exploring this central question." Yet at the present rate that the habitat of these wonderful creatures is being destroyed, that great natural experiment is likely to be brought to an abrupt end only a few decades after Goodall began her work. Hence her efforts to raise awareness of their plight and her involvement in a range of international projects – including Roots & Shoots, her environmental youth program – which is aimed at protecting African habitats and chimpanzee homelands.

1.

What were Goodall’s key findings from her work with chimpanzees? What are the implications of her work/discoveries?

2.

Many psychologists, like Jane, work with animals as opposed to humans. Yet they seek to understand the same things – underlying mental processes and behavior of particular subjects. If you were to conduct naturalistic observations on any animal, which would it be and why? What would you seek to understand/uncover?