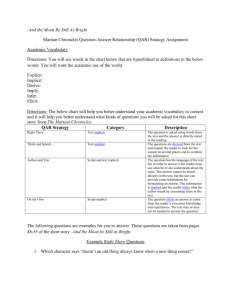

Mad Pain and Martian Pain - University of San Diego Home Pages

Mad Pain and Martian Pain

David Lewis

Why isn’t the Identity Theory a No-

Brainer?

• Science says that the mind is the brain, so what’s the problem?

• The problem is that we want to make sense of the “is”: what is identical to what?

– mental state types to brain state types?

– mental states to functional states?

• Analytic philosophy assumes that “Philosophy leaves everything as it is”

– it never contradicts science or, insofar as possible, common sense and does not provide any alternative “vision” of reality: it analyzes scientific and commonsensical claims, looks for problems, spells out details, finds inconsistencies and, if possible, fixes them.

The Madman

• There might be a strange man who sometimes feels pain

…but whose pain differs greatly from ours in its causes and effects…his pain does not occupy the typical causal role of pain.

• Mad pain (if it is possible) would be a counterexample to

– (“Analytical” or “Logical”) Behaviorism: talk about mental states should be analyzed as talk about behavior and behavioral dispositions

– Functionalism: mental states are to be characterized in terms of their causal relations to sensory inputs, behavioral outputs and other mental states, that is, in terms of their functional role.

The Martian

• There might be a Martian who sometimes feels pain

…but whose pain differs greatly from ours in its physical realization…[though] the effects of his pain are fitting: his thought and activity are disrupted, he groans and writhes.

• Martian pain (if it is possible) is a counterexample to

• The Identity Theory (Type-Physicalism): mental states are identical to (so nothing more than) brain states

• On this account, for every actually instantiated mental property F, there is some physical property G such that F=G: pain—not just this occurrence of pain—is the firing of C-fibers in the way that heat—not just this occurrence of heat—is molecular motion.

What a Theory of Mind Must Do

A credible theory of mind needs to make a place both for mad pain and for

Martian pain…But the lesson of mad pain is that pain is associated only contingently with its causal role, while the lesson of Martian pain is that pain is connected only contingently with its physical realization.

• Contingent isn’t good enough because we want to understand the concept of pain (or any other mental state)—an a priori characterization—since philosophy can’t tell us anything about contingent matters of fact.

• However we need an account that accommodates the fact that the connection between pain and both its normal causal role and physical realization for humans is contingent.

• So neither behaviorism nor type-type identity theory nor the version of functionalism suggested by Turing will do.

III. The Martian Problem

The concept of pain, or indeed any other experience or mental state, is the concept of a state that occupies a certain causal role…a state apt for being caused in certain ways by stimuli plus other mental states and apt for combining with certain other mental states to jointly cause certain behavior.

• The Martian Pain problem is the problem of multiple realizability: intuitively, even if the state which realizes (plays the pain role) for normal humans is the firing of C-fibers, it could, and likely is, realized by other kinds of states for other kinds of creatures.

• Note: Lewis will identify pain with the role-player rather than the abstract role: in humans the brain state that realizes the pain role; in Martians whatever physical state realizes pain for them.

• Compare other accounts in which the role itself is the mental state.

Pain is a Non-rigid concept

‘[P]ain’ is a nonrigid designator. It is a contingent matter what state the concept and the word apply to.

• Note Lewis is rejecting Kripke’s claim that “pain,” like “heat,” picks out the same phenomenon at all possible worlds.

• At any world, whatever it is that plays the pain-role, is pain.

• At our world, for normal humans, the firing of C-fibers plays the pain role.

• At other worlds, or for other populations, some other state might play the pain-role so

• If pain is identical to a certain neural state, the identity is contingent

Contingent Identity?!!??

• NO! The statement “Pain is the firing of C-fibers” is contingent because

“pain” is not a rigid designator: pain is a role.

I do not say that here we have two states, pain and some neural state, that are contingently identical…What’s true is, rather, that the concept and name of pain contingently apply to some neural state at this world, but do not apply to it at another.

• Compare: it is contingent that, in 2010, Barak Obama is President not because at some other possible world Obama ≠ Obama but because at some other world someone other than Obama plays the Presidential role.

Our cat Bruce is necessarily self-identical. What is contingent is that the nonrigid concept of being out cat applies to Bruce rather than to some other cat or none.

De Dicto and De Re

• Referring expressions can play two different roles:

– De Dicto: refer to whatever individual has a certain property or plays a certain role:

• Example: “I believe that the President is Commander in Chief”

• I had a civics class and know that according to the Constitution, whoever is President is also Commander in Chief—I know this even if I don’t know who’s President now.

– De Re: pick out an individual via some property he has or role he plays

• Example: “I believe of the President that he’s Commander in Chief.”

• I know that this guy (who is in fact President) is Commander in

Chief—I see him in a military-style uniform giving orders or whatever.

Modality De Dicto and De Re

• Could the loser of the last Presidential race have won? Yes and no.

– No de dicto: An individual can’t both lose and win the same contest.

– Yes de re: That guy McCain could have won

• Could pain fail to be pain?

– No de dicto: pain is pain is pain: nothing can both be pain and not be pain.

– Yes de re: this state, the state that plays the pain role, could have failed to play that role.

IV. Different Populations

• If a nonrigid concept or name applies to diferent states in different possible cases, it should be no surprise if it also applies to different states in different actual cases.

• Our problem is the problem of non-human and deviant cases so we need to consider the problem of applying mental state concepts to such cases at the actual world.

• Lewis strategy is to relativize mental state concepts to populations:

• We may say that some state occupies a causal role for a population…if and only if, with few exceptions, whenever a member of that population is in that state, his being in that state has the sort of causes and effects given by the role….the Martian is in pain because he is in a state that occupies the causal role of pain for Martians, whereas we are in pain because we are in a a state that occupies the role of pain for us.

But isn’t this just plain functionalism?

• Two differences:

– Lewis identifies mental states with role-players, e.g. with the firings of

C-fibers, inflation of the Martian hydraulic system, etc. rather than with the abstract functional state which is the role they play.

– Lewis characterizes such states as aptnesses to be caused and cause other states: that is, they don’t necessarily or always have those causes and effects but, within a given population, typically do.

• Lewis will characterize mental states in this way in order to cope with the problems that Mad Pain poses.

The Mad Pain Problem

• The madman is in a state (C-fibers firing) that occupies the causal role of pain for a population consisting of typical (non-mad) human beings.

• The C-fiber firing state he’s in however doesn’t plays the pain role for him or his fellow madmen.

• Relative to humans he’s in a state apt for having the causes and effects of pain

• Humans are the relevant population for him because he’s human

• But: why are humans rather than mad humans the appropriate population?

Criteria for Appropriate Population

• We may say that X is in pain simpliciter if and only if X is in the state that occupies the causal role of pain for the appropriate population. But what is the appropriate population?

• Four Criteria for appropriate population: A state, S, is pain for an individual

X when at least some of the following conditions are met:

1.

S plays the pain role for humans

2.

S plays the pain role for a population to which X belongs

3.

S plays the pain role for a population in which X is not exceptional

4.

S plays the pain role for a population that constitutes a natural kind

Balancing the Criteria

Since the four criteria agree in the case of the common man, which is the case we usually have in mind, there is no reason why we should have made up our minds about their relative importance in cases of conflict.

• Normal human pain meets all four conditions

• Normal Martian pain fails (1) but satisfies (2) – (4): it’s what plays the pain role in (2) the population to which X belongs (3) as an unexceptional member and (4) that population is a natural kind.

• Mad human pain fails (3) since madmen are exceptional but (1) plays the pain role in the human species (2) of which X is a member and (4) that species is a natural kind.

• Mad Martian pain fails (1) and (3), but satisfies (2) and (4) since (2) it plays the pain role for a population to which X belongs and that population is a natural kind.

Discovery and Decision

• Since normal human pain satisfies all 4 conditions, it’s unquestionably pain

– This is the answer we want because we’re analyzing our concept of pain, which grew up in response to these paradigm cases

• Normal Martian and mad human pain satisfy 3 out of 4 conditions, which accords with our intuitions that these are clearly cases of pain

– Again as desired—and considering these puzzle cases shows that we’re on the right track in recognizing that both causal role and right physical state matter in understanding our concept of pain

• Mad Martian which satisfies 2 out of 4 is negotiable

• In a range of even further out cases there is no determinate fact of the matter: no answer to the question of whether X is in pain

No determinate fact of the matter?

• The last two cases seem crazy

– How can it be negotiable, depend on the intuitions of 3 rd parties concerning the appropriate reference population and weighing of criteria, whether X is in pain or not?

– How can there be no fact of the matter about whether an individual is in pain or not?

• Lewis is deploying a kind of argument that figures in a range of cases where we want to understand a concept, check ‘puzzle cases’ and recognize that for some there is no right answer: we’ll consider this form of argument.

• The question is whether this kind of argument works for pain.

Paradigm and Deviant Cases

• We want to understand some commonsensical concept, C, that arose in reference to a range of ‘normal,’ central or paradigm cases

• To see that our tests/evidences for something’s being C aren’t just accidental we consider puzzle cases

– Example: even though fingerprints are evidence for personal identity, they aren’t criterial: not part of our concept of personal identity

• We come up with a criterion for being C that all ‘normal’ cases and those puzzle cases in which we have clear intuitions satisfy

• This criterion should show also why borderline cases are borderline

• And why, in cases where we’re baffled, there is no right answer: why they’re at best matters for decision rather than discovery.

Some Examples

• A religion is a practice which, in for central cases involves (1) beliefs or some sort, (2) claims about the supernatural, (3) public ceremonies and

(4) embodiment in an institution.

• Anglicanism, a paradigm case meets all 4 conditions—as desired

• Unitarianism fails (2) but satisfies the other conditions

• Neo-Paganism Druidism fails (4) but satisfies the other conditions

• Do-it-yourself New Age “spirituality” fails (3) and (4)

• For a range of “philosophies,” self-help programs, etc. there is no right answer was to whether they’re religions or not

Another Example

• How can there be “no right answer”?

• Consider the criteria for something’s being an “historical landmark”

• Paradigm cases were built before a certain date and not seriously modified, reconstructed or moved from their original sites.

– The Presidio is a fake, but was designated an historical landmark in

1960 in virtue of being at the site of the original Presidio

– The Victorians in Old Town were moved from original sites

– There will be cases of buildings that have been modified, moved or reconstructed about which there is no right answer: we can decide (for the purposes of designating landmarks) whether they count or not since there is no right answer.

The Inverted Spectrum

• We ask: does this kind of argument work for pain or other qualitative

(phenomenal or “feely”) mental states?

• Compare “feely” states, like pain, visual experience, etc. with states like belief, desire, etc. that don’t essentially involve any “feely” component

– It seems plausible to suggest that when it comes to non-feely states, there is no right answer in some cases

– But it seems less plausible for “feely” states: consider inverted spectrum

• Lewis claims however that “there is no determinate fact of the matter” in the inverted spectrum case—and that other cases: Is this OK?

Mad, Alien and Unique

We have a place for commonplace pain, mad pain, Martian pain, and even mad Martian pain…What about pain in a a being who is mad, alien and unique?...I think we cannot and need not solve this problem. Our only recourse is to deny that the case is possible

• Mad, unique aliens fail all criteria so on this account pain in such beings is impossible

• Is this a counterexample to Lewis’ account or can we accept this result?

• It assumes that there is no intrinsic character of mental states that makes them pain: no intrinsic “what it is like”

• And this is contrary to what Friends of Qualia suggest

Phenomenal Character

Only if you believe on independent grounds that considerations of causal role and physical realization have no bearing on whether a state is pain should you say that they have no bearing on how that state feels.

• Lewis responds to the objection by Friends of Qualia that his account of pain as a role-playing concept overlooks the intrinsic character of phenomenal states: what they are like:

• For a state to be pain and for it to feel painful are…one and the same. A theory of what it is for a state to be pain is inescapably a theory of what it is like to be in that state.

• Is this good enough? Friends of Qualia can explain why causal role and physical realization seem to have some relevance: they’re epistemic criteria, evidences in the way that fingerprints are.

Postscript: The Knowledge Argument

• Lewis considers Jackson’s argument for qualia in “What Mary Didn’t

Know” (which we’ll read)

• When Mary, who knows all the physical facts about color vision, leaves her black and white room and sees red for the first time, she comes to know something she didn’t know before.

• Prima facie it seems that what she comes to know is what red is like

• Lewis suggests however that what she comes to know is how to do certain things:

• [K]nowing what it’s like is the possession of abilities: abilities to recognize, abilities to imagine, abilities to predict one’s behavior

Lewis’ Functionalism

• Lewis account is a sophisticated version of functionalism:

• Our concept of any mental state is the concept of a state apt for being caused by certain stimuli and apt for causing certain behavior

– Different from simple type-type Identity Theory since it allows for multiple realizability by characterizing states in terms of causal role

– Different from Turing-style Functionalism since it identifies the mental state with the role-playing physical state rather than the abstract role

• But like functionalism and the identity theory, it has a problem with…