ETHICS AND MOARLITY Chapter 1: why be ethical?

advertisement

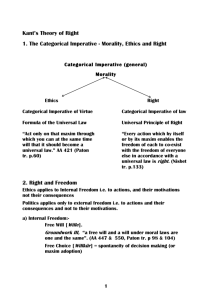

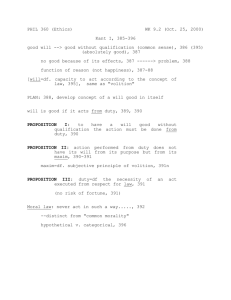

DEONTOLOGICAL ETHICS In ethical theories, if we mainly focus on the action itself, then we use deontological ethics (also known as deontology or duty ethics). In duty ethics, an action is morally right if it is in agreement with moral rules/norms. There are four central duty theories. The first is that championed by 17th century German philosopher Samuel Pufendorf, who classified dozens of duties under three headings: DUTIES TO GOD, DUTIES TO ONESELF, and DUTIES TO OTHERS. Concerning our duties towards God, he argued that there are two kinds: a theoretical duty to know the existence and nature of God, and a practical duty to both inwardly and outwardly worship God. Concerning our duties towards oneself, these are also of two sorts: duties of the soul, which involve developing one’s skills and talents, and duties of the body, which involve not harming our bodies, as we might through gluttony or drunkenness, and not killing oneself. Concerning our duties towards others Pufendorf divides these between absolute duties, which are universally binding on people, and conditional duties, which are the result of contracts between people. Conditional duties involve various types of agreements, the principal one of which is the duty is to keep one’s promises. Absolute duties are of three sorts: avoid wronging others, treat people as equals, and promote the good of others. Rights Theory A second duty-based approach to ethics is rights theory. Most generally, a “right” is a justified claim against another person’s behavior – such as my right to not be harmed by you. Rights and duties are related in such a way that the rights of one person imply the duties of another person. For example, if I have a right to payment of $10 by Smith, then Smith has a duty to pay me $10. This is called the correlativity of rights and duties. The most influential early account of rights theory is that of 17th century British philosopher John Locke, who argued that the laws of nature mandate that we should not harm anyone’s life, health, liberty or possessions. These are our natural rights, given to us by God. Following Locke, the United States Declaration of Independence authored by Thomas Jefferson recognizes three foundational rights: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Jefferson and others rights theorists maintained that we deduce other more specific rights from these, including the rights of property, movement, speech, and religious expression. There are four features traditionally associated with moral rights. A third and more recent duty-based theory is that by British philosopher W.D. Ross, which emphasizes prima facie duties. Like his 17th and 18th century counterparts, Ross argues that our duties are “part of the fundamental nature of the universe.” However, Ross’s list of duties is much shorter, which he believes reflects our actual moral convictions: Fidelity: the duty to keep promises Reparation: the duty to compensate others when we harm them Gratitude: the duty to thank those who help us Justice: the duty to recognize merit Beneficence: the duty to improve the conditions of others Self-improvement: the duty to improve our virtue and intelligence Nonmaleficence: the duty to not injure others Ross recognizes that situations will arise when we must choose between two conflicting duties. In a classic example, suppose I borrow my neighbour’s gun and promise to return it when he asks for it. One day, in a fit of rage, my neighbour pounds on my door and asks for the gun so that he can take vengeance on someone. On the one hand, the duty of fidelity obligates me to return the gun; on the other hand, the duty of nonmaleficence obligates me to avoid injuring others and thus not return the gun. Prima Facie According to Ross, I will intuitively know which of these duties is my actual duty, and which is my apparent or prima facie duty. In this case, my duty of nonmaleficence emerges as my actual duty and I should not return the gun. Prima Facie (on its first appearance, or at first sight ~ the literal translation would be "at first face"), is used in modern legal English to signify that on first examination, a matter appears to be self-evident from the facts. (But remember appearances can be deceptive ex. smoking gun) IMMANUEL KANT (1724-1804) Born and raised in Prussia (N.E. Germany) Grew up in poverty-stricken, but very religious Protestant family Family were Pietists – believed in personal devotion and Bible reading Lived near home all his life (never went beyond 100 km of his birthplace) His life was all about routine – everything was nearly scheduled Mr. Kant: Teacher and Author After university, Kant worked as a private tutor and teacher He became a university professor of logic and metaphysics Kant wrote books – difficult to understand Critique of Pure Reason took 12 years to write and contains the longest sentences ever written. He greatly influenced Western thought and philosophy Immanuel Kant Like Aristotle, Kant also held that “the good” is the aim of a moral life. But he approached the question of how one attains the good in quite a different way. He recognized that in the domain of ethics we cannot arrive at the same type of certainty as we can in physics and math. Ethics does not present us with rational cognitive certainty but with practical certainty. In this practical area of our lives, he held that there are three areas of interest: God Freedom Immortality We may not be able to prove any of these empirically, nonetheless, we need these practical principles to be able to pursue and attain the supreme good. Graphic Organizer for Kantian Ethics AUTONOMY OF THE WILL Kant held that a person should decide for him/herself the moral laws that he/she will follow. A person should place a moral norm upon him/herself and obey it. This is his/her duty. For Kant, you are your own legislator. It is your autonomy, your decision to act in accordance with your good will. You are not constrained by another. He called this ability to decide for oneself “autonomy of the will.” In this respect, Kant’s ethics are more individual based than Aristotle’s. To Aristotle, a “good person” seeks his/her happiness within the context of a community. Heteronomy is allowing someone or something else to decide the moral laws that one will follow. Kant’s ethics are to be discovered in private life, in the inner convictions and autonomy of the individual. THE GOOD WILL Kant argues that nothing is good in itself except a “good will.” Facets of human personality such as intelligence and judgement and virtues such as courage, determination and perseverance are perhaps good and desirable, but only if the will that makes use of them are good. It is the same with gifts of fortune of fortune such as power, wealth and honour. These will produce pride and conceit unless the person has a good will, which can correct the influence these have upon the mind and ensure that it is adapted to its proper end. Moreover, an impartial rational spectator would not feel any pleasure at seeing a person without a good will enjoying continuous happiness without deserving it. A “good will” is a will that is motivated to perform an act because it is a “moral duty” and not merely because the act is in one’s self-interest or gives one pleasure. For Kant, a human action is morally good when it is done for the sake of duty. An act of kindness to a friend may be praiseworthy but it is not a moral act. It becomes moral when you are busy or when you are more inclined to do other things. For example, you might not want to go to your great aunt’s funeral, but it is your duty. You chose to go to honour the family. Real moral worth is motivated by duty, not by inclination (desire). In other words, moral worth is measured not by the results of one’s actions, but by the motive behind them. Kant’s language is full of “should”. It is a language not of desires but of “ought.” MAXIMS By will, Kant meant the uniquely human capacity to be motivated by reasons or “maxims.” Kant argues that humans are capable of determining through reason what is morally correct. To be motivated by duty is to be motivated to do something because one believes it is the way that all human beings ought to behave. Acting morally then is acting only on those maxims or reasons that you believe everyone – universally – ought to live up to. For Kant, my will is “good without qualification” only if it always has in view one principle: Would I still perform the actions that I plan to perform if I knew that my maxims (reasons) would become laws of nature that everyone would have to follow? If not, then I should not perform the action. CATEGORICAL IMPERATIVE Kant argued that moral duties or imperatives are categorical —they should be obeyed without exception. Individuals should do what is morally right no matter what the consequences are. A great analogy is unconditional love. That is love without limitation, exception or condition. For example, it is wrong to not care for our children even if it results in some great benefit, such as financial savings. A categorical imperative is fundamentally different from a hypothetical imperative that hinges on some personal desire or belief that we have, for example, Kant believes that there is just one command or imperative that is categorical. He believes that from this one categorical imperative, this universal command, we can derive all commands of duty. Kant’s categorical imperative states: I should never do something unless 1. it is possible for everyone to do it and the practice still remains 2. I am willing to have everyone do it According to Kant, “what is right for one is right for all.” When applying the first categorical imperative... We need to ask ourselves one question: Would I want everyone else to make the decision I did? If the answer is yes, the choice is justified. If the answer is no, the decision is wrong. Example #1: Would it be morally right to break a promise in order to suit your own purposes? Ask yourself: Is it possible for everyone make promises and then break them when it is convenient? Reason: Clearly breaking promises like this could not become something that everyone does, because then people would stop making promises altogether. Who would accept anyone’s promise, knowing that everyone breaks promises when it is convenient for them? Larger Picture: Once everyone starts breaking promises, then promises are no longer possible. Example: If enough people made such false promises, the banking industry would break down because lenders would refuse to provide funds. Ask yourself: Am I willing to have everyone break promises in order to suit their own purposes? Reason: No because then no one would accept promises that I would make with them. Who would accept anyone’s promise knowing that everyone breaks promises when it is convenient for them? Conclusion: Since it is not possible for everyone to make promises and break them when it is convenient, it is wrong for you to do so. It is wrong to make exceptions for ourselves: if everyone cannot do something, then doing it is wrong for me. Note that Kant does not argue that the consequences of a universal practice would be bad and therefore the practice is bad. Instead he claims that the practice is self-contradictory; the practice itself becomes impossible once everyone does it. His appeal is to logical consistency, not to consequences. Ask yourself: Is it possible for everyone to cheat on exams? Reason: Clearly cheating on exams could not become something that everyone does, because then people would stop using exams to assess people altogether. Who would accept anyone’s mark on an exam as a true measure of what they have learned, knowing that everyone obtains the answers from elsewhere? Larger Picture: Once everyone begins cheating on exams, then the practice of using exams as assessments of an individual’s learning are no longer possible. Example: If enough people cheated on exams, employers or people who employ professional occupations would have no way of knowing who is truly qualified for a position. Ask yourself: Am I willing to have everyone cheat on exams? Reason: No because then I might the services of one who needs to be knowledgeable in that area of service and I may need them to do the best job possible ex. Neurosurgeon. (Would you like it if you found out that your neurosurgeon cheated on all his/her exams?) Conclusion: Since it is not possible for everyone to cheat on exams, it is wrong for you to do so. It is wrong to make exceptions for ourselves: if everyone cannot do something, then doing it is wrong for me. Ask yourself: Is it possible for everyone to refuse to help others when they are in great need? Reason: Actually it is possible for everyone to refuse help to others who are in great need. Ask yourself: Am I willing to have everyone refuse help to the needy? Reason: No because then I might need others to desperately help me one day. No one would be willing to live in a world where no one ever helped those in great need, although such a world is possible. Conclusion: Since it is not possible for everyone to refuse helping the needy, it is wrong for you to do so. It is wrong to make exceptions for ourselves: if everyone cannot do something, then doing it is wrong for me. So even Kant believes that there are some actions that are wrong, not because it is impossible for everyone to do them, but because we are not willing to have everyone do them. Kant’s Second Categorical Imperative “So act in such a way as to treat humanity, whether in your own person or in that of any other always as a means and never merely as We should always treat ourselves an end.” and other people with dignity, and never use them or ourselves as mere instruments to achieve some selfish purpose. Kant also argued for the importance of treating people as an end, and never as a means to an end. For Kant, we treat people as an end whenever our actions toward someone reflect the inherent value of that person. Every person has a fundamental human dignity that gives her person value “beyond all price.” Thus it is wrong to use people or manipulate them without their consent for our own selfish desires. Others can help us reach our objectives, but they should never be considered solely as a means to an end. We should, instead, respect and encourage the capacity of others to choose for themselves. Kant expanded his view on this second version of the categorical imperative using the following four dimensions; Strict duty to oneself: A person who is thinking of committing suicide should ask himself whether his action is consistent with the idea that humanity is an end in itself. If he kills himself to escape his suffering, he is using himself as a means to maintain a tolerable existence. But a person is not a thing. A person cannot be used merely as a means, but must be respected as an end in himself. Strict duty to others: Is it wrong to lie or to steal from a person? Clearly if we lie or steal we are using other people as means to achieve our own interests but furthermore, lying or stealing involves doing something to a person without his free and knowing consent. Morality requires that we always give others the opportunity to decide for themselves whether or not they will join us in our actions. This rules out all forms of deception, force, coercion and manipulation. Meritorious duty to oneself: We should also refrain from violating our own humanity as an end in itself, but we should also try to make our actions harmonize with the fact that our humanity is such an end. When we neglect to develop our abilities we are not doing something that is destructive of humanity as an end in itself. But such neglect clearly does not advance humanity as an end in itself. Meritorious duty to others: Donating to charity in order to genuinely help others, for example, is morally correct since this acknowledges the inherent value of the recipient. The second version of Kant’s imperative implies that we should promote people’s capacity to choose for themselves. It also implies that we should strive to develop this capacity in ourselves and in those around us (for example, through education). Furthermore, Kant would say that when people are in great need, their ability to choose for themselves is compromised. Since we have a duty to promote people’s capacity to choose for themselves, we should help those whose poverty prevents them from exercising their capacity to choose for themselves. By contrast, we treat someone as a means to an end whenever we treat that person as a tool to achieve something else. It is wrong, for example, if we give to charity in order to achieve a break on our taxes. ELABORATING ON KANTS IDEA OF HUMANITY AS AN END According to Kant (and Aristotle, if you remember) we are rational and autonomous beings with the capacity for reason and freedom to choose. Person’s have absolute value (intrinsic value) not relative value. Kant argues that humanity and the capacity to reason are undifferentiated in all of us. – This is what makes us all EQUAL. Respect for Kant is respect for humanity which is universal. In this way Kantian respect is unlike: LOVE (I love this person because they have certain qualities I admire) SYMPATHY (I can relate to that person because they shared a similar experience) SOLIDARITY (I will support this particular group of people because we share the same ideals) ALTRUISM (I will sacrifice my life for this person because they are related to me) All of the above reasons for caring for people have to do with who they are in particular. So the reason I should respect the dignity of others doesn’t have to do with something in particular about them, it is because I can identify the same dignity in them that I have in myself. In the end….violating my own dignity is like violating it in another. Criticisms of Kantian Theory Kant’s imperative is a simple yet powerful ethical tool. Not only is the principle easy to remember, but asking if we would want our behaviour to be made into a universal standard should also prevent a number of ethical miscues. Emphasis on duty builds moral courage. Those driven by the conviction that certain behaviours are either right or wrong no matter what the situation are more likely to blow the whistle on unethical behaviour, resist group pressure to compromise personal ethical standards, Follow through on their choices Kant’s emphasis on respecting the right of others to choose is an important guideline to keep in mind when making ethical choices in organizations. This standard promotes the sharing of information and concern for others while condemning deceptive and coercive tactics. Through all this Kant also reminds us to take care of ourselves. Influenced by Pufendorf, Kant agreed that we have moral duties to oneself and others, such as developing one’s talents. Criticism #1 In Kant’s theory, rules cannot be bent. This reminds us of absolutism. So, the question arises whether all the moral laws form a consistent system of norms. Critiques of Kant’s system of reasoning often center on his assertion that there are universal principles that should be followed in every situation. In almost every case, we can think of exceptions. For instance, many of us agree that killing is wrong yet support capital punishment for serial murderers. We value privacy rights but have given many up in the name of national security. Then, too, how do we account for those who honestly believe they are doing the right thing even when they are engaged in evil? “Consistent Nazis” were convinced that killing Jews was morally right. They wanted their fellow Germans to engage in this behaviour; they did what they perceived to be their duty. Criticism #2 Another downside is that Kantian theory prescribes to rigidly adhere to the rules, irrespective of the consequences. But in real life, following a rule can of course have very negative consequences. The acts that the categorical imperative says are always wrong do not always seem wrong. For example, Kant says that it is absolutely wrong ever to lie, no matter what good might come from telling a lie. Yet is it wrong to lie to save your life? To save someone from serious pain or injury? Kant’s theory does not deal with these exceptions and there is no compelling reason why certain actions should be prohibited without exception. Apparently Kant failed to distinguish between persons making no exceptions to rules and rules having no exceptions. If a person should make no exceptions to rules, then one should never except oneself from being bound by a rule. But it does not therefore follow that the rule has no exceptions. Criticism #3 Conflicting duties also pose a challenge to deontological thinking. Complex ethical dilemmas often involve competing obligations. For example, we should be loyal to both our bosses and coworkers. Yet being loyal to a supervisor may mean breaking loyalty with peers, such as when a supervisor asks us to reveal the source of a complaint when we’ve promised to keep the identity of that co-worker secret. How do we determine which duty has priority? Kant’s imperative offers little guidance in such situations. Criticism #4 There is one final weakness in Kant’s theory that is worth noting. By focusing on intention, Kant downplayed the importance of ethical action. Worthy intent does little good unless it is acted out. We typically judge individuals based on what they do, not on their motives.