12 Years a Slave

“Befuddled: Who Defines Racism?”

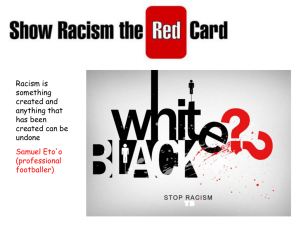

When the worship associates team asked me to take the pulpit for this date, the date we remember and celebrate the work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., I was ecstatic because Martin Luther King is one of my American heroes. That ecstasy lasted about 24 hours. Then strange feelings and a sense of apprehension and confusion began to pervade my thoughts—more than just typical nerves. What would I talk about? Recent events have ignited explosive discussions about racism, discrimination, hate and violence, provoking many to civil disobedience;

1 others, to thoughtful discussion, love and compassion. Marvin Gaye’s soul classic

“What’s Goin’ On?” a pensive song reflecting on the turbulent 60’s, seemed to speak as much now as then. Should I address our progress in these 50 years since

Selma, and take an optimistic tone? Or should I address our lack of progress, the continuing fight for social justice, and try to put a positive spin on this? Or, I could try to make meaning of recent events in Ferguson, and many others incidents around the nation. As I began to peel away the layers of possible topics, I came to the core: definition. If we are to understand racism, and begin to unpack its ugly history, we must first define it, because defining racism defines our attitudes and reactions to racism. Defining racism is one key to understanding racism.

But, who holds the magic key? Does the dictionary have the authority to define racism?

(Slide #1: definition)

I’m certain Merriam-Webster would lay claim to that:

1. a belief that race is the primary determinant of human traits and capacities and that racial differences produce an inherent superiority of a particular race

2. racial prejudice or discrimination

Well, it’s a start. The dictionary provides a clear denotation, which lacks any

2 connotations, and therein lies the rub. It’s not so academic because we all come to racism from different perspectives. What are our stories? Where did we grow up?

What kinds of homes were we raised in? Is racism inherent in us, a sociobiological phenomenon, or is it a learned behavior? We know it exists, but how we define it—that’s a little trickier. The word itself has only been around about 150 years, coined from the French word racisme, but the concept has been with us since the dawn of man. Ultimately, we must look beyond the dictionary because racism engulfs our culture, and why each of us defines it a little differently.

Surely Martin Luther King has the authority to define racism. I’ve certainly pondered what he might have to say about recent events and civil unrest, although I think we would all agree he would be saddened, and perhaps saddened to see, as well, that progress in our society’s fight against racial injustice has indeed been slow, and it has become abundantly clear that we have work ahead. As we find ourselves at the 50 th Anniversary of Selma, we look to Martin Luther King as an authority and guide, and we read his words as inspiration to our souls and our rationale minds. In this revealing anecdote, it is clear he began to put the pieces of racism together at a young age:

“My mother, as the daughter of a successful minister, had grown up in comparative comfort. She had been sent to the best available school and college and had, in general, been protected from the worst blights of discrimination. But

my father, a sharecropper’s son, had met its brutalities at first hand, and had begun

3 to strike back at an early age.

“I remembered riding with him [one day in my childhood] when he accidentally drove past a stop sign. A policeman pulled up to the car and said, ‘All right, boy, pull over and let me see your license.’

“My father replied indignantly, ‘I’m no boy.’ Then, pointing to me,

‘This is my boy. I’m a man, and until you call me one, I will not listen to you.’

“The policeman was so shocked that he wrote the ticket up nervously and left the scene as quickly as possible.

“With this heritage, it is not surprising that I had… learned to abhor segregation, considering it both rationally inexplicable and morally unjustifiable.”

Racism is certainly being defined by example for the young child. Like many of

King’s words, these are loaded with implications. He learns he is considered different, but is perhaps not sure why. He learns that language has implications, although he may not fully understand them. He notices this makes the policeman nervous. And as he reflects on the experience as an adult, he makes the most salient observation, that the incident was “both rationally inexplicable and morally unjustifiable.” Rationally inexplicable and morally unjustifiable. What is striking about this statement is its keen observation that racism cannot be rationally explained, or morally justified. Again, I think most Unitarian Universalists would agree with King’s assertions, but not everyone in history, and not everyone today would do the same.

If King were alive in today’s culture, I wonder what he would make of the media influence on this issue. Does the media have the authority to define racism?

Certainly, it is defined in countless media outlets; in fact, this non-stop information

overload can be overwhelming, confusing, contradictory and downright befuddling.

Countless writers, from academics to journalists, from philosophers to politicians, and novelists to poets have all taken a turn defining racism. Add the power of imagery to these words, and the definitions become a little clearer. If you’ve seen these movies, you remember them: Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, Crash and

Gran Torino spin racism in a contemporary culture. While Roots and 12 Years a

4

Slave slap slavery right in the face, movies like Driving Miss Daisy , Imitation of

Life, 42, and the just released Selma offer us various cultural and sociological views and interpretations of racism. Far too many television shows have taken on the issue of racism to begin naming them, but those of Norman Lear, particularly, the groundbreaking mother of them all, All in the Family with its racist protagonist

Archie Bunker, became household names, when the 70’s ushered a new era of racial commentary into the living rooms of America.

Talk radio is notorious for its slanderous commentary. Today’s high-speed internet, with its endless stream of information and countless social media venues perhaps define racism for us, both explicitly and implicitly, more than any other force in today’s culture. Social media and the internet are just—frightening. While these avenues provide an open window for discussion, those discussions, circling the globe, provide a few too many perspectives, making it difficult and confusing to sort out bias, intent and propaganda. Want a more personal perspective? Try striking up a discussion on racism at your next family function. Or, you can strike up a casual conversation while waiting in line at the grocery store.

No, it’s not an easy topic to talk about—discussing the wonderful direction and acting in 12 Years a Slave is not the same conversation as discussing how 12 Years

5 a Slave reveals and defines the roots of racism in this country. A word of warning if you find yourself in a discussion on racism: expect to find, in these sometimes real and sometimes hypothetical discussions, a quick disregard for factual history and reasoned argument—oh yes, logic.

Perhaps this is what King meant by racism being irrational and morally unjust:

(Slide #2: the billboard)

Take a look at this spin on “reasoned” thinking: This billboard, sponsored by the

Ku Klux Klan, welcomes visitors to Harrison, Arkansas. Now, I have family and friends in Northwest Arkansas who would be horrified by this billboard—but clearly, for some in this region, this defines racism. For innocent and naïve children who may be confused, their parents will explain this “logic,” but unfortunately, it won’t be the same explanation the young Martin Luther King received from his father. In our fast-paced and multi-ethnic culture, we are bombarded with words and images on a continual basis—mentally sorting through this information and making sense of it is a monumental task.

To complicate matters even more, the commentary on, and interpretations of racism through the media, good propaganda or bad, brings up unbelievably complicated questions about free speech. The recent incident in Paris—just one more example.

Everyone in this room understands, and agrees: racism is complicated.

(Slide #3: the brain)

6

Does science have the authority to define racism? A recent article in Mother Jones titled “The Science of Your Racist Brain” offers an interesting perspective.

Neuroscientist David Amodio posits that a small region of the brain, the amygdala, reacts when we see those of a different race, and that reaction is based in fear—a sort of biological defense mechanism. Coined “implicit racial bias” by psychologists, the tentacles of this hidden racism can affect interpersonal behavior, policy, employment practices and public life. Studies, tests and the subsequent conclusions reveal that the amygdala may cause us to (and note here—these are sub-conscious behaviors that we ourselves do not realize)

1.

Associate skin color with physical, rather than mental abilities;

2.

Maintain physical distance;

3.

Not Vote for Obama;

4.

Be subjected to racial bias at the doctor’s office

At its core, the theory seems to imply that, biologically we have an innate fear and an inherent need for self-survival; biologically, we are all racist, and consequently, we spend our lives in a quest for racial equality, against biological odds. But

Amodio is also clear on this point: we have the capacity to control both our fear, and our behavior. Many sitting in the congregation today participated in this online discussion, and I was brought to tears reading many of your thoughtful reflections, but I could not bring myself to the point of calling myself a racist, although I certainly understood the arguments, I have faith in science, and I’m willing to admit—I have moments when I simply cannot understand why I might have had a questionably racist thought, or uttered a questionably racial epithet.

(black out slide #3)

Does this generation have the authority to define racism? I can assure you, I have learned a great deal from working with teenagers the past 27 years, not to mention my parents and grandparents (whose behavior and words were more often racist than not). Hopefully most discussions of racism are evolving discussions, revealing growth compassion and understanding—at least in an ideal world.

I teach a classic novel I’m betting 90% of you have read,

The Adventures of

Huckleberry Finn. Mark Twain’s biting satire on the failures of Reconstruction and the emotional wreckage of slavery are not without controversy—something

7

Twain would surely relish today. Considered one of the most frequently banned books in high school curriculums, Twain boldly employs the word “nigger” 219 times—bold now, not so bold then, when the novel was dished for it “lack of proper grammar.” Not being a fan of censorship, I have been careful over the years in my introduction of the novel. I’ve covered my tracks, and prepared my defense, but that defense has changed in the course of just a few years. In 2002 when

Harvard Professor of black studies Randall Kennedy published his book Nigger , a thorough and fascinating study of the etymology of this strange word, he defends

Twain’s use of the word for literary merit, as have many other scholars. This was just one small piece we read in defense of the novel, over a five-day introduction.

Today, the introduction is one day long, and the discussions upon reading the novel get longer, and longer.

This year, as we concluded our reading, I asked kids what resources they had used, and what commentary they had found, outside the required reading. In a dangerous act of permissive behavior, I allowed a kid access to the computer on my desk, the internet, and a large screen projector. Trusting as I was, he called up a site known as thugnotes.com

. A clearly intelligent black scholar, acting as a black-thug stereotype, offers hysterical commentary and insightful analysis on the

novel. And even though we covered irony from 50 angles in class, I think, oh my god, this clip is just racist. Well, we can have that argument, and as a teacher I am obligated to pursue that argument, but to this generation, and the multi-ethnic classrooms of today, those thugnotes were both hysterical, and educational—and

8 just to make sure, I always encourage honest criticism and anonymous feedback— but this seems to be my paranoia—not theirs. This generation does not struggle with the issue in the same way as baby-boomers; this generation seems to not struggle with the issue as much as the previous generation, the Gen-Xers. If anything, the issue seems to befuddle many of them. Chalk it up to suburban naiveté? Seclusion and inexperience? Maybe, but we seem to be moving forward.

Believe me, we can, and must, trust this generation to re-define the word.

Merriam-Webster. Dr. Martin Luther King. David Amodio, the media, the classroom, and the current generation provide but a few glimpses of how we define, and consequently how we react to racism.

We know the forces we fight outside the walls of this sanctuary—and they can be overwhelming. Unitarian Universalists define racism through our faith and living our seven principles. Although racism may be “a belief that race is the primary determinant of human traits and capacities and that racial differences produce an inherent superiority of a particular race,” this definition only provides fodder for our actions. We as individuals and Unitarian Universalists must define racism by fighting racism. We as individuals and Unitarian Universalists must use our heads, our ability to reason and employ logic and knowledge, in our fight against racism, stereotypes and intolerance. We, as individuals and Unitarian Universalists, have the authority to re-define racism as the fight against racism. Raise your voice— call out injustice where you see it; write your political representatives or local

9 paper; move your feet—VUU offers countless activities to further social justice.

We must trust our instincts, and trust our hearts. Our actions help us define racism, and our actions are those of love and compassion. While our little amygdales may evoke fear, and our environmental influences may evoke the occasional racial

“sin,” we must navigate the confusion and fear by guiding our mission with the oars of love. Above all, we must live our seven principles.

(Slide #4: MLK)

Tomorrow, we honor a civil rights legend, and man who put his life on the line in a massive effort to extinguish racism and prejudice. Martin Luther King said,

“Everybody can be great. Because anybody can serve. You don’t have to have a college degree to serve. You don’t have to make your subjects and your verbs agree to serve. You don’t have to know about Plato and Aristotle to serve. You don’t have to know Einstein’s theory of relativity to serve. You don’t have to know the second theory of thermodynamics in physics to serve. You only need a heart full of grace. A soul generated by love.”

Love is the doctrine of this congregation. Our actions, as Unitarian Universalists, are framed in love and reason. Please, join me now in reciting our covenant:

(Bring covenant up on the screen)

Love is the doctrine of this congregation; the quest of truth is our sacrament, and service is our prayer. To dwell together in peace; to seek knowledge in freedom; to serve humankind in friendship; thus we do covenant.

If recent events in our nation have befuddled you, confused you, caused you to wonder “What’s going on?” just remember: “we’ve got to find a way, to bring some lovin’ here today.”

10

(begin music—low)

As we extinguish this flame, a symbol of our faith and the pursuit of social justice, please, go in peace, with love in your hearts.

(music up full)