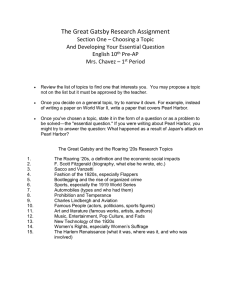

world war ii unit - education532portfolio

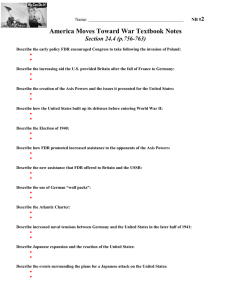

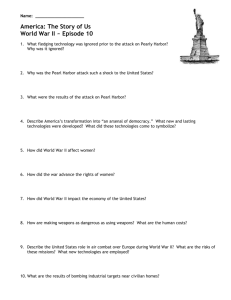

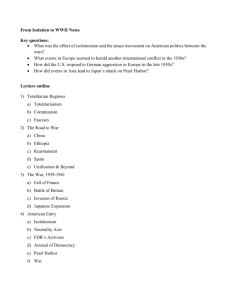

advertisement