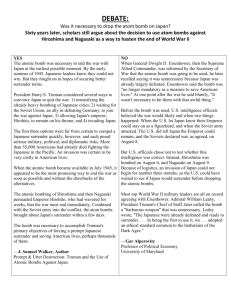

Pro and Con Arguments on the Decision to Drop the Bomb By Bill

advertisement

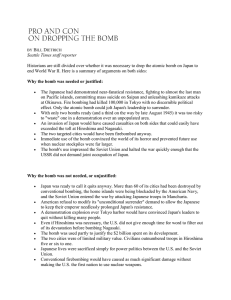

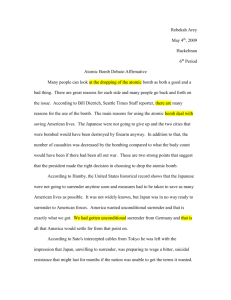

Pro and Con Arguments on the Decision to Drop the Bomb By Bill Dietrich Seattle Times staff reporter Historians are still divided over whether it was necessary to drop the atomic bombs on Japan to end WW2. Here is a summary of arguments on both sides. Why the bomb was needed or justified: The Japanese had demonstrated near-fanatical resistance. Fighting to almost the last man on Pacific islands, committing mass suicide on Saipan and unleashing kamikaze attacks at Okinawa. Firebombing had killed 100,000 in Tokyo without producing a surrender. Only the atomic bomb could jolt Japan’s leadership to surrender. With only two bombs ready (and a third on the way by late August 1945) it was too risky to "waste" one in a demonstration over an unpopulated area. A US invasion of Japan would have caused casualties on both sides that could have exceeded the toll at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The 2 targeted cities would have been firebombed anyway. The bomb's use impressed the Soviet Union and halted the war quickly enough that the USSR did not demand joint occupation of Japan. Immediate use of the bomb convinced the world of its horror and prevented future use when nuclear stockpiles were far larger. Why the bomb was not needed, or unjustified Japan was ready to call it quits anyway. More than 60 of its cities had been destroyed by conventional bombing, the home islands were being blockaded by the American Navy and the Soviet Union entered the war by attacking Japanese troops in Manchuria US refusal to modify its "unconditional surrender" demand to allow the Japanese to keep their emperor needlessly prolonged Japan's resistance. A demonstration explosion over Tokyo harbor would have convinced Japan's leaders to quit without killing many people. Even if Hiroshima was necessary, the US did not give enough time for word to filter out of its devastation before bombing Nagasaki. The bomb was used partly to justify $2 billion on its development. The 2 cities were of limited military value, civilians outnumbered troops in Hiroshima 5 to 1. Conventional firebombing would have caused as much significant damage without making the US the first nation to use nuclear weapons. Japanese lives were sacrificed simply for power politics between the US and the USSR. The Atomic Bomb …America’s greatest victory was yet to come. Her principal enemy, Japan, was still undefeated. Fighting intensified as the U.S. began to concentrate its effort in the Pacific Theater after the defeat of Hitler. As early as February, B-29 bombers based in the Marinas had begun devastating fire bombing raids on the cities of the Japanese mainland. The same month, in the costliest landing in the Marine Corps history, the island stronghold of Iwo Jima was captured. In April the island of Okinawa, less than three hundred miles from Japan, was invaded; on June 22, after the loss of over seven thousand American lives, it was declared officially under U.S. control. And less than a month later, on July 16, occurred what was perhaps the most significant event in the war against Japan, perhaps in the history of western civilization, when the first atomic bomb was detonated in Alamogordo, New Mexico. As early as 1939, American physicists had been convinced that uranium could be used to create a new source of unprecedented power. They were also concerned that Germany, which was believed to be conducting atomic research, might be first to harness this power and incorporate it into weapons of unparalleled destruction. Albert Einstein wrote a letter to Franklin Roosevelt that convinced him the Allies must move quickly to be the first to develop atomic weapons. German sites where it was believed atomic research was being carried out were bombed, and in 1942, the Manhattan Engineer District project to develop an atomic bomb was set up under the direction of General Lealie R. Groves. Noted physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer was given the responsibility of building and testing the bomb. The first atomic bomb was tested at 5:30 A.M. in the desert near Los Alamos, New Mexico, and an official War Department release would later describe it as “a revolutionary weapon destined to change war as we know it or may even be the instrumentality to end all wars.” Oppenheimer later said that as he watched the incredible explosion through his binoculars, he thought: “I am become Death, the shatterer of worlds”. The irony of the atomic bomb- that its creation and use would end the war, yet have the potential to destroy the worldcontinued to torment Oppenheimer for the rest of his life. But it was left to Truman to make the agonizing decision to use it. Churchill knew about the Manhattan Project, and shortly before the test he gave Truman, in principle, his consent to drop the bomb on Japan. Stalin did not know about it, and Truman decided not to inform him until the forthcoming Potsdam conference which Truman scheduled to take place just after the test. With the knowledge that the bomb test was successful, Truman had hoped the Potsdam conference would devote considerable time to questions of ending the war in Japan. But the conference, from July 17 to August 2, instead concentrated on the postwar division of Germany, reparations, and the peace treaties to be made with the defeated nations. Truman mentioned to Stalin that the United States had developed a weapon of unusual destructive force. “The Russian Premier showed no special interest,” Truman noted in his memoirs. “All he said was that he was that he was glad to hear it and hoped we would ‘make good use of it against the Japanese.” But the very next day, Stalin put five Soviet physicists under the direction of secret-police chief Lavrenty Beria and ordered them to catch up with the Americans in the development of atomic weapons. The nuclear race was underway: Four years later Russia would explode its first atomic bomb; three years after that, the United States tested a hydrogen bomb, which Russia duplicated two years later. Meanwhile, Truman intended to follow Stalin’s advice and use the atomic bomb against the Japanese: “Let there be no mistake about it. I regarded the bomb as a military weapon and never had any doubt that it should be used.” General George Marshall, Chief of Staff, told Truman that an invasion of Japan would probably result in a half-million American casualties and that it would probably be late 1946 before Japan surrendered. And Truman’s scientific advisors told him that “we can propose no technical demonstration likely to bring an end to the war; we see no acceptable alternative to direct military use.” Truman decided he wanted it dropped as nearly as possible upon a war production center of prime military importance. The city of Hiroshima was targeted from a list of four potential sites picked by the Joint Chiefs. On August 6, as Truman was returning from the Potsdam conference on the cruiser Augusta, he was given the message: “BIG BOMB DROPPED ON HIROSHIMA AUGUST 5 AT 7 P.M. WASHINGTON TIME. FIRST REPORTS INDICATE COMPLETE SUCCESS WHICH WAS EVEN MORE CONSPICUOS THAN EARLIER TEST.” Truman first telephoned Secretary of State Brynes, and when he hung up, he turned to the group of sailors standing around him and said “This is the greatest thing in history. It’s time for us to get home.” Truman ordered a second bomb dropped, on Nagasaki, on August 9. It produced the desired effect; the Japanese surrendered on August 14. Many Americans at the time agreed with the managing editor of the Washington Times – Herald, Frank Waldrop, who said, “I don’t give a damn how many Japanese were killed; it was Americans who made the difference. And if the Japanese didn’t want to get bombed they shouldn’t have started the monkey business they did… The President of the United States has an obligation to the corn farmers in Iowa, never mankind. Nobody knows who mankind is. Yet he knows who the people of the United States are and it was their sons who were out there getting killed.” Before long however, the doubting would begin. Oral historian Studs Terkel says: “At the time I felt – wow- the war would be over… Later on, the horror hit me. Remember when Einstein heard the news; he is reputed to have said ‘I wish I were a locksmith.” When America heard the news of the surrender, celebrations erupted spontaneously all across the country. “It was wild,” said David Soergal, a Wisconsin engineer who just happened to be at Times Square on V-J Day, September 2. “You couldn’t walk through the streets- 42nd and Broadway was just a mess of humanity.” Mary Studwell, a teenager in Stanford, Connecticut, recalled: “They just stopped everything, including the buses. I lived about three miles outside the main body of town, and a whole bunch of us teenagers walked down into town and formed a big conga line.” Said Alison Arnold, the society editor for the Boston Herald, in Duxbury, Massachusetts: “I remember driving home from work one night listening to the radio, and all of a sudden it came over that the thing was over. And at almost every house, the door opened and children poured out waving flags. The church bells were ringing. Everybody got into their cars and drove around town with the horns blowing.” The Final Act Controversy over a museum exhibit in Washington, D.C. revived an old debate: Did the U.S. have to drop the atomic bomb on Japan? By Herbert Buchsbaum A blockbuster exhibit was supposed to open at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. The Enola Gay, the B-29 bomber that dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945, had been restored and was to be the centerpiece of a major exhibit about the bomb and its victims. The exhibit was to show how the bomb figured in the war, both in military and human terms. It sought to tell the dramatic story of how the world’s top physicists raced the clock to invent a powerful new weapon. At a more personal level, the exhibit would have contained the story of a class of 500 Japanese high school girls who happened to be standing near the spot where the bomb was dropped. The point, exhibit organizers said, was to provoke thought and debate on the world’s first dropping of an atomic bomb. But as soon as the plans became public, a firestorm of debate engulfed the exhibit itself. World War II veterans’ groups attacked the exhibit for concentrating on the Japanese victims of the bomb rather than on Japan’s aggression during the war. The Air Force Association charged that the exhibit was “a slap in the face to all Americans who fought in World War II.” And some members of the U.S. House of Representatives demanded the dismissal of the museum’s director. When the Smithsonian revised the exhibit, however, historians complained that it had caved into pressure that the new exhibit was inaccurate and politicized. The museum revised the exhibit again and again, but finally gave up. The Enola Gay still went on display. But there was only a small plaque beside it and nothing else. The furor over the exhibit reflects the fierce controversy that remains over the atomic attacks themselves. Years after Americans are still coming to grips with the decision to drop the bomb. Was it the necessary evil required to bring a swift end to the war? Or was it needless overkill that ushered in an era of nuclear fear? Certain facts are clear. At 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, the Enola Gay dropped its payload, a 10-foot-long, 9000-pound bomb nicknamed Little Boy. Seconds later, 2000 feet above Hiroshima, a city of half a million people, the bomb exploded. A blinding “thousand-sun” light flashed through the sky. Trains were tossed hundreds of feet in the air. Steel girders melted like wax. People simply vaporized. About 100,000 people died instantly. A shock wave leveled houses miles away. Vapor and ash boiled up in a giant mushroom cloud above the city. Thousands of burn victims leaped into the city’s rivers to ease their pain, unknowingly poisoning themselves in the contaminated water. As the vapor cooled, a sticky, radioactive “black rain” began to fall. Another 100,000 people would die later from burns, radiation, and cancer caused by the radiation. Was such suffering justified? Total War At the time, the U.S. was in the midst of total war against an enemy whose atrocities were well documented. The Japanese had slaughtered some 140,000 civilians in Nanking, China, in 1937. And they had started the war against the U.S. by bombing the American naval base at Pearl Harbor in 1941. By 1945, Japanese and American troops were fighting for the control of the Pacific, island by island. In February more than 6,000 U.S. Marines and 20,000 Japanese died fighting for the tiny island of Iwo Jima. Weeks later, 16,000 Americans and 110,000 Japanese were killed in the battle for the island of Okinawa. Though Japan had suffered costly defeats, officials predicted a fight to the finish. President Harry S. Truman was preparing to invade Japan, which could have cost tens of thousands of casualties. Then he was offered a new option—a bomb described as “the most terrible weapon ever known in human history.” For Truman, dropping the bomb “was never any decision you had to think about,” he said. “It was my responsibility as President to force the Japanese warlords to come to terms as quickly as possible with the minimum loss of lives.” Three days after the bombing of Hiroshima, a second bomb was dropped on the city of Nagasaki, killing another 79,000. Five days after that, Japan surrendered. But critics—some at the time, more after the event—have said the bomb was not necessary. “The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons,” Admiral William Leahy, one of the war’s top military planners, wrote in 1950. Some U.S. strategists said later that the war would have likely ended in a few weeks anyway. Japan had begun to seek peace talks through intermediary countries. But historians disagree as to whether Truman knew this at the time. In 1945, some officials had argued for dropping the bomb on a military installation instead of a heavily populated city. A group of leading scientists, including the bomb’s inventors, were urging the government to invite Japanese officials to witness a test explosion in an unpopulated area to persuade them to surrender. Truman rejected these ideas. The U.S. had only two bombs then and no one knew for sure whether they would work. If a public test failed, his advisors argued, Japanese resistance could stiffen. And to the military, which had already bombed 66 Japanese cities, the atomic bomb was just one more bomb, Hiroshima just one more city. Meanwhile hundreds of American soldiers were dying every day. But was Little Boy just one more bomb? The bomb that ended the war also launched a perilous nuclear arms race. Since then, some 50,000 nuclear warheads have been produced, which continue to threaten the survival of the entire world. Today, a single hydrogen bomb contains the same power of 1,540 Little Boys. Would these weapons have arrived eventually anyway? Yes or no, the debate continues. Debating Hiroshima By Gar Alperovitz Though most people are unaware of it, numerous once secret documents show that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki almost certainly were completely unnecessary. We now know, for instance, that the United States had broken the Japanese code early in the Second World War and that top officials were desperately seeking to end the fighting. When told the atomic bomb would be used, General Dwight Eisenhower was deeply depressed: “Japan was at that very moment seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of “face”… It wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing…” Already Defeated Admiral William D. Leahy, presiding officer of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, felt that “the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against the Japanese…The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender…” Millions of American service-men believe that the atomic bomb saved their lives. However, the planned invasion of Japan was eight months in the future; even the invasion of the southern island of Kyushu was three months off. The documents now available show that President Harry Truman had two ways to end the war without the bomb: He was advised two months before Hiroshima that if he assured Japanese officials they could keep their emperor; this was likely to produce surrender. Truman’s second option was simply to await the Russian declaration of war scheduled for August 8, 1945. U.S. intelligence advised that, when the massive Russian Red Army entered the war, Japan was likely to collapse. Hiroshima was bombed on August 6, Nagasaki on August 9. President Truman’s diaries, lost until 1978, make it unmistakably clear he understood what was going on. The President privately termed the most important intercepted cable “the telegram from the Jap emperor asking for peace.” Many of the once secret papers show a major reason Truman rejected other ways to end the war was that he and his top advisers were beginning to think as much-or more- about the impact of the atomic bomb on Russia as on Japan. For instance, the President postponed his Potsdam meeting with Stalin until the day after the first atomic test because he wanted to be sure the new weapon- which Secretary of War Stimson called the “master card” of diplomacy- really worked before negotiating postwar arrangements with the Soviet leader. Read the Report At Potsdam, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill recognized the relationship of the bomb to diplomacy: when Truman “got to the meeting after having read this report (of the successful test) he was a changed man. He told the Russians just where they got on and off and generally bossed the whole meeting. “ Secretary of State James F. Byrnes, the main official advising Truman, expressed himself privately to atomic scientist Leo Szilard two months before Hiroshima. Byrnes “did not argue that it was necessary to use the bomb against the cities of Japan in order to win the war…” Szilard observed: “Mr. Byrnes view (was) that possessing and demonstrating the bomb to Russia would make Russia more manageable.” Warren Brown, Byrnes assistant, noted in his diary in July 1945 that the President’s chief adviser was “hoping for time, believing that after (the) atomic bomb Japan will surrender and Russia will not get in so much on the kill…” In early 1945, U.S. leaders may have believed an invasion would be necessary if the atomic bomb was not used. However, after that time- with the intercepted cable showing Japan’s dramatic collapse in June and July- the record shows that top military figures understood the war was all but over. At present available evidence does not answer all the questions concerning the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Nonetheless serious historians now recognize that considerations related to Russia played a major, if not central, role in the decision to use the atomic bomb. Gar Alperovitz is the author of the book, “Atomic Diplomacy: Hiroshima and Potsdam” (Viking Press) By Chalmers M. Roberts Washington Post For years many Americans, and foreigners too, have been contending that the United States never should have dropped the bomb on Hiroshima, that Japan was already so battered and beaten it was on the point of surrender. They reject the counter-argument that only use of that dreadful weapon forced the surrender and thus avoided the heavy loss of life inevitable if the planned invasion of Japan had taken place. The record, however, shows that Harry Truman chose to drop the bomb essentially to end the war in a hurry and save American lives. In his 1955 memoirs, Truman wrote “In all, it had been estimated that it would require until the late fall 1946 to bring Japan to her knees.” And: “General Marshall told me that it might cost half a million American lives to force the enemy’s surrender on his home grounds.” Secretary of War Stimson wrote in his 1947 memoirs that the invasion plans would involve military and naval forces “of the order of five million men” or more, and that “we estimated that if we should be forced to carry this plan to its conclusion, the major fighting would not end until the latter part of 1946, at the earliest. I was informed that such operations might be expected to cost over a million casualties to American forces alone.” Stimson called the use of the bomb “our least abhorrent choice” for ending the American fire raids, lifting the blockade and avoiding the “ghastly specter of a clash of great land armies…” In his public report at the war’s end, General Marshall wrote that “defending the homeland the enemy had an army of two million, and remaining air strength of 8,000 planes of all types.” After leaving the presidency, Truman in a television interview said “it was estimated” that that the initial invasion of the southeastern most island of Kyushu, Operation Olympic, “would cost over 700,000 men-250,000 of our youngsters to be killed and 500,000 of them to be maimed for life.” Those figures doubtless stretch any 1945 estimate. But Truman that day also referred to another key factor in his decision: the murderous Okinawa campaign that had lasted from April 1 to June 21 and had cost 48,000 American casualties. Also affecting the Truman decision was the mass employment of so-called suicide aircraft, or kamikaze. The toll on American ships by these one-way pilots had been the greatest in the navy’s history: 30 vessels sunk and 368 ships damaged including 10 battleships and 13 aircraft carriers. A U.S. Fleet Headquarters estimate as of August 9, the day the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, totaled the Japanese army and navy aircraft still available in the home islands as 3,669 and of these 1,115 were in western Japan, the Kyushu area. By that time I was a military intelligence officer in the Pentagon in charge of tracking the kamikaze units in the air force on the basis of intercepted Japanese military messages. At the war’s end I was flying over the initial invasion beach, at Miyazaki on Kyushu. I was heading an eight man team checking up on our intelligence estimates, part of the U.S. Strategic Bomb Survey. The Miyazaki beach, barely 30 miles long, looked like an ideal landing spot, long and gentle sloping to the sea, the biggest beach on the island. But it was terribly shallow, and behind it rose a range from which murderous fire on the beaches would have been possible. At Oita, in northern Kyushu, we found Japanese planes loaded for kamikaze pilots. At Karasehara, further south, the now meek Japanese officers furnished order-of-battle documents to show that at war’s end they had 56,000 troops dug in with another 70,000 in reserve, and that there were many planes, 850 regular planes plus 750 suicide planes. A Japanese general told me “we were figuring on 1,000 planes, special-attack kamikaze type” for defense against the allied landings on Kyushu. In 1948 Secretary Stimson obviously depended on such figures in writing that “the air force had been reduced mainly to reliance upon kamikaze, or suicide, attacks. These latter, however, had already inflicted serious damage on our sea-going forces, and their possible effectiveness in a last-ditch fight was a matter of real concern to our naval leaders.” Stimson summarized: “As we understood in July, there was a very strong possibility that the Japanese government might determine upon resistance to the end…In such an event the Allies would be faced with the enormous task of destroying an armed force of 5 million men and 5,000 suicide aircraft, belonging to a race which had already amply demonstrated its ability to fight literally to the death.” Atomic Bomb Questions 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. American physicists believed that this element could be used in atomic bombs? Which country did the United States fear would build the bomb first? Where was the first atomic bomb detonated? What is “ironic” about the atomic bomb? Do you agree? Explain. What was the nuclear arms race? On what date was Hiroshima bombed? What date was Nagasaki bombed? What was Truman’s response when he heard Hiroshima had been bombed? Do you agree with Frank Waldrop’s opinion? Why or why not? Explain. 9. 10. 11. 12. The Final Act Describe what happened in Hiroshima after the bomb exploded? How many people died in Hiroshima? How many people died in Nagasaki? What did some officials encourage the U.S. to do instead of dropping the bomb on Hiroshima? What was the problem with this idea? 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. Debating Hiroshima What did the U.S. find out from cracking the Japanese code? Did General Dwight D. Eisenhower think the bomb was necessary? What were Truman’s other two options for ending the war with Japan? Was there another reason why Truman wanted to drop the bomb on Japan? What was it? Is this acceptable? Explain. According to Truman’s diary, how many U.S. lives could have been lost with an attack of mainland Japan? Who were Kamikaze pilots? Opinion Questions 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. Were both bombs necessary in ending WWII? Were either of the bombs necessary in ending WWII? Is it moral to drop bombs on civilians? Is it fair to use knowledge we have now to judge decisions made 70 years ago? Explain. Do you think that the president and his advisors knew that the destruction would be so bad? If no, do you think this would have influenced his decision? 24. If you were president at the end of WWII, would you order the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Why or why not?