Always Further: Following in the Footsteps of La Salle

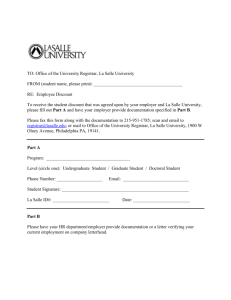

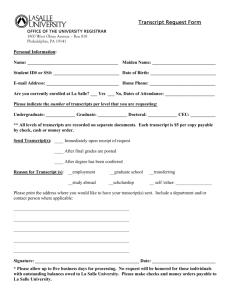

advertisement