Measuring teacher and principal

effectiveness

Laura Goe, Ph.D.

Research Scientist, ETS, and Principal Investigator for the

National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality

Workshop Presentation to

Nebraska Leadership Committee

Lincoln, NE April 19, 2012

Laura Goe, Ph.D.

• Former teacher in rural & urban schools

Special education (7th & 8th grade, Tunica, MS)

Language arts (7th grade, Memphis, TN)

• Graduate of UC Berkeley’s Policy, Organizations,

Measurement & Evaluation doctoral program

• Principal Investigator for the National

Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality

• Research Scientist in the Performance Research

Group at ETS

2

The National Comprehensive Center

for Teacher Quality

• A federally-funded partnership whose

mission is to help states carry out the

teacher quality mandates of ESEA

• Vanderbilt University

• Learning Point Associates, an affiliate of

American Institutes for Research

• Educational Testing Service

3

Today’s presentation available online

• To download a copy of this presentation go

to www.lauragoe.com

Go to Publications and Presentations page

Today’s presentation is at the bottom of the

page

4

To be discussed…

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

A new era in teacher and principal evaluation

An aligned systems of teacher and principal evaluation

Developing a shared vocabulary

Components of teacher and principal evaluation systems

Student, parent, and staff feedback measures

Professional responsibility measures and other valued actions

Weighting components of the evaluation model

Frontier and rural school models

Professional growth opportunities aligned with evaluation results

Merit pay and teacher retention

Teacher preparation programs

Principal evaluation standards and instruments

Moving forward: next steps

5

The goal of teacher evaluation

The ultimate goal of all

teacher evaluation should be…

TO IMPROVE

TEACHING AND

LEARNING

6

Trends in teacher evaluation

• The policy imperative to change teacher evaluation

has outstripped the research

Though we don’t yet know which model and combination of

measures will identify effective teachers, many states and

districts feel compelled to move forward at a rapid pace

• Inclusion of student achievement growth data

represents an important “culture shift” in evaluation

Communication and teacher/administrator participation and

buy-in are crucial to ensure change

• The implementation challenges are considerable

We are models exist for states and districts to adopt or adapt

Many districts have limited capacity to implement comprehensive

systems, and states have limited resources to help them

7

It’s an equity issue

• Value-added research shows that teachers

vary greatly in their contributions to student

achievement (Rivkin, Hanushek, & Kain,

2005).

• The Widget Effect report (Weisberg et al.,

2009) found that 90% of teachers were

rated “good” or better in districts where

students were failing at high levels

8

An aligned teacher evaluation system:

Part I

Teaching

standards: high

quality state or

INTASC standards

(taught in teacher

prep program,

reinforced in

schools)

Measures of

teacher

performance

aligned with

standards

Evaluators

(principals,

consulting

teachers, peers)

trained to

administer

measures

Instructional

leaders (principals,

coaches, support

providers) to

interpret results in

terms of teacher

development

High-quality

professional

growth

opportunities for

individuals and

groups of teachers

with similar

growth plans

9

An aligned teacher evaluation system:

Part II

Results from teacher

evaluation inform

evaluation of

teacher evaluation

system (including

measures, training,

and processes)

Results from teacher

evaluation inform

planning for

professional

development and

growth

opportunities

Results from teacher

evaluation and

professional growth

are shared (with

privacy protection)

with teacher

preparation

programs

Results from teacher

evaluation and

professional growth

are used to inform

school leadership

evaluation and

professional growth

Results from teacher

and leadership

evaluation are used

for school

accountability and

district/state

improvement

planning

10

“Effective” vs. “Highly Qualified”

• The focus has shifted away from ensuring

highly qualified teachers in every

classroom to ensuring effective teachers

in every classroom

• This shift is a result of numerous studies

that show that qualifications provide a

“floor” or “minimum” set of competencies

but do not predict which teachers will be

most successful at helping students learn

11

Definitions in the research & policy

worlds

• Much of the research on teacher effectiveness

doesn’t define effectiveness at all though it is

often assumed to be teachers’ contribution to

student achievement

• Bryan C. Hassel of Public Impact stated in 2009

that “The core of a state’s definition of teacher

effectiveness must be student outcomes”

• Checker Finn stated in 2010 that “An effective

teacher is one whose pupils learn what they

should while under his/her tutelage”

12

Definitions in the research & policy

worlds (2)

Anderson (1991) stated that “… an effective

teacher is one who quite consistently

achieves goals which either directly or

indirectly focus on the learning of

their students” (p. 18).

13

Definitions in the research & policy

worlds (3)

Hunt (2009) stated that, “…the term “teacher

effectiveness” is used broadly, to mean the

collection of characteristics, competencies, and

behaviors of teachers at all educational levels that

enable students to reach desired outcomes, which

may include the attainment of specific learning

objectives as well as broader goals such as being

able to solve problems, think critically, work

collaboratively, and become effective citizens.

(p. 1)

14

Goe, Bell, & Little (2008) definition of

teacher effectiveness

1. Have high expectations for all students and help students learn, as

measured by value-added or alternative measures.

2. Contribute to positive academic, attitudinal, and social outcomes for

students, such as regular attendance, on-time promotion to the next

grade, on-time graduation, self-efficacy, and cooperative behavior.

3. Use diverse resources to plan and structure engaging learning

opportunities; monitor student progress formatively, adapting

instruction as needed; and evaluate learning using multiple sources of

evidence.

4. Contribute to the development of classrooms and schools that value

diversity and civic-mindedness.

5. Collaborate with other teachers, administrators, parents, and

education professionals to ensure student success, particularly the

success of students with special needs and those at high risk for

failure.

15

Race to the Top definition of

effective & highly effective teacher

Effective teacher: students achieve acceptable rates

(e.g., at least one grade level in an academic year) of

student growth (as defined in this notice). States,

LEAs, or schools must include multiple measures,

provided that teacher effectiveness is evaluated, in

significant part, by student growth (as defined in this

notice). Supplemental measures may include, for

example, multiple observation-based assessments of

teacher performance. (pg 7)

Highly effective teacher students achieve high rates

(e.g., one and one-half grade levels in an academic

year) of student growth (as defined in this notice).

16

Measures and models: Definitions

• Measures are the instruments,

assessments, protocols, rubrics, and tools

that are used in determining teacher

effectiveness

• Models are the state or district systems of

teacher evaluation including all of the inputs

and decision points (measures, instruments,

processes, training, and scoring, etc.) that

result in determinations about individual

teachers’ effectiveness

17

Teaching standards

• A set of practices teachers should aspire to

• A teaching tool in teacher preparation programs

• A guiding document with which to align:

Measurement tools and processes for teacher

evaluation, such as classroom observations, surveys,

portfolios/evidence binders, student outcomes, etc.

Teacher professional growth opportunities, based on

evaluation of performance on standards

• A tool for coaching and mentoring teachers:

Teachers analyze and reflect on their strengths and

challenges and discuss with consulting teachers

18

Who should be at the table?

• “An SEA must meaningfully engage and solicit input

from diverse stakeholders and communities in the

development of its request.” (NCLB Waiver

application, pg. 15)

A description of how the SEA meaningfully engaged and

solicited input on its request from teachers and their

representatives.

A description of how the SEA meaningfully engaged and

solicited input on its request from other diverse communities,

such as students, parents, community-based

organizations, civil rights organizations, organizations

representing students with disabilities and English

Learners, business organizations, and Indian tribes.

19

Multiple measures of teacher

effectiveness

• Evidence of growth in student learning and

competency

Standardized tests, pre/post tests in untested subjects

Student performance (art, music, etc.)

Curriculum-based tests given in a standardized manner

Classroom-based tests such as DIBELS

• Evidence of instructional quality

Classroom observations

Lesson plans, assignments, and student work

Student surveys such as Harvard’s Tripod

Evidence binder (next generation of portfolio)

• Evidence of professional responsibility

Administrator/supervisor reports, parent surveys

Teacher reflection and self-reports, records of contributions

20

Teacher observations: strengths and

weaknesses

• Strengths

Great for teacher formative evaluation (if observation is

followed by opportunity to discuss)

Helps evaluator (principals or others) understand

teachers’ needs across school or across district

• Weaknesses

Only as good as the instruments and the observers

Considered “less objective”

Expensive to conduct (personnel time, training,

calibrating)

Validity of observation results may vary with who is

doing them, depending on how well trained and

calibrated they are

21

Why teachers generally value

observations

• Observations are the traditional measure of teacher

performance

• Teachers feel they have some control over the

process and outcomes

• They report that having a conversation with the

observation and receiving constructive feedback

after the observation is greatly beneficial

• Evidence-centered discussions can help teachers

improve instruction

• Peer evaluators often report that they learn new

teaching techniques

22

When teachers don’t value

observations, it’s because…

• They do not receive feedback at all

• The feedback they receive is not specific

and actionable

• The observer suggests actions but is

unable to offer the means and resources to

carry out those actions

Mentors/coaches, other support personnel

Time for individual growth planning/activities

Protected time for collaboration with others

23

Validity of classroom observations is

highly dependent on training

• A teacher should get the same score no matter

who observes him

This requires that all observers be trained on the

instruments and processes

Occasional “calibrating” should be done; more

often if there are discrepancies or new observers

Who the evaluators are matters less than

adequate training

Teachers should be trained on the observation

forms and processes

24

Reliability results when using different

combinations of raters and lessons

Figure 2. Errors and

Imprecision: the reliability of

different combinations of

raters and lessons. From Hill

et al., 2012 (see references

list). Used with permission of

author.

25

Cincinnati study results

• Study by Kane et al. (2010) used teacher evaluation

scores plus value-added scores

“…policies and programs that help a teacher get better

on all eight ‘teaching practice’ and ‘classroom

environment’ skills measured by TES will lead to student

achievement gains” (p. 28)

“…helping teachers improve their ‘classroom

environment’ management will likely also generate higher

student achievement” (p. 28)

“…[adding] pedagogy that utilizes ‘questioning and

discussion’ practices will generate higher reading

achievement, but not higher math achievement” (p. 28)

26

Value-added models

• Many variations on value-added models

TVAAS (Sander’s original model) typically uses

3+ years of prior test scores to predict the next

score for a student

- Used since the 1990’s for teachers in Tennessee, but

not for high-stakes evaluation purposes

- Most states and districts that currently use VAMs use

the Sanders’ model, also called EVAAS

There are other models that use less student

data to make predictions

Considerable variation in “controls” used

27

27

Growth vs. Proficiency Models

Achievement

Proficient

In terms of

growth,

Teachers A

and B are

performing

equally

Teacher A:

“Success” on

Ach. Levels

Teacher B:

“Failure” on Ach.

Levels

Start of School Year

End of Year

Slide courtesy of Doug Harris, Ph.D, University of Wisconsin-Madison

28

Growth vs. Proficiency Models (2)

Achievement

Proficient

Teacher A

A teacher

with lowproficiency

students can

still be high

in terms of

GROWTH

(and vice

versa)

Teacher B

Start of School Year

End of Year

Slide courtesy of Doug Harris, Ph.D, University of Wisconsin-Madison

29

Most popular growth models:

Colorado Growth Model

• Colorado Growth model

Focuses on “growth to proficiency”

Measures students against “academic peers”

Also called criterion‐referenced growth‐to‐standard

models

• The student growth percentile is

“descriptive” whereas value-added seeks

to determine the contribution of a school or

teacher to student achievement

(Betebenner 2008)

30

An illustration of student growth over time

in Denver, CO

Slide courtesy of Damian Betebenner at www.nciea.org

31

What value-added and growth models

cannot tell you

• Value-added and growth models are really

measuring classroom, not teacher, effects

• Value-added models can’t tell you why a

particular teacher’s students are scoring

higher than expected

Maybe the teacher is focusing instruction

narrowly on test content

Or maybe the teacher is offering a rich,

engaging curriculum that fosters deep student

learning.

• How the teacher is achieving results matters!

32

Measuring teachers’ contributions to

student learning growth (classroom)

33

Race to the Top definition of student

growth

• Student growth means the change in

student achievement (as defined in

this notice) for an individual student

between two or more points in time. A

State may also include other

measures that are rigorous and

comparable across classrooms. (pg

11)

34

34

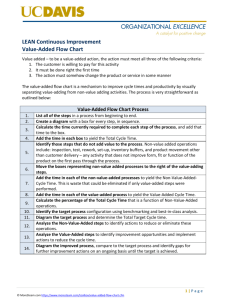

Measuring teachers’ contributions to student learning

growth: A summary of current models

Model

Description

Student learning

objectives

Teachers assess students at beginning of year and set

objectives then assesses again at end of year; principal

or designee works with teacher, determines success

Subject & grade

alike team models

Teachers meet in grade-specific and/or subject-specific

teams to consider and agree on appropriate measures

that they will all use to determine their individual

contributions to student learning growth

Pre-and post-tests

model

Identify or create pre- and post-tests for every grade

and subject

School-wide valueadded

Teachers in tested subjects & grades receive their own

value-added score; all other teachers get the schoolwide average

35

School-wide VAM illustration

8

7

6

5

4

Obs/Surv

VAM

3

2

1

0

36

DC Impact: Score comparison for

Groups 1-3

Group 1

(tested

subjects)

Group 2

(non-tested

subjects)

Group 3

(special

education)

Teacher value-added (based

on test scores)

50%

0%

0%

Teacher-assessed student

achievement (based on nonVAM assessments)

0%

10%

10%

Teacher and Learning

Framework (observations)

35%

75%

55%

The rest of the 100%: All teachers receive 10% “Commitment to School Community” and 5%

schoolwide average value-added. In addition, Special Education teachers receive 10% for IEP

timeliness and 10% Eligibility timeliness (“…a measure of the extent to which the special

education eligibility process required for the students on your caseload is completed within

37

the timeframe”).

Validity

• There is little research-based support for the

validity of using student growth measures for

teacher evaluation

Mainly because using student growth

measures in evaluation hasn’t been done

• Herman et al. (2011) state, “Validity is a

matter of degree (based on the extent to

which an evidence-based argument justifies

the use of an assessment for a specific

purpose).” (pg. 1)

38

IF

Standards clearly define learning

expectations for the subject area

and each grade level

AND

Assessment scores represent

teachers’ contribution to student

growth

THEN

AND IF

The assessment instruments have

been designed to yield scores that

can accurately reflect student

achievement of standards

Student growth scores accurately

and fairly measure student

progress over the course of the

year

AND IF

AND

There is evidence that the

assessment scores actually measure

the learning expectations

Interpretation of

scores may be

appropriately

used to inform

judgments about

teacher

effectiveness

The assessment instruments have

been designed to yield scores that

accurately reflect student learning

growth over the course of the year

AND IF

Copyright © 2009 National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality. All rights reserved.

Propositions that justify the use of these measures for evaluating teacher effectiveness. (Adaptation based on Bailey & Heritage, 2010 and

Perie & Forte (in press)) (Herman, Heritage & Goldschmidt, 20ll ). Slide used courtesy of Margaret Heritage.

Validity is a process

• Starts with defining the criteria and

standards you want to measure

• Requires judgment about whether the

instruments and processes are giving

accurate, helpful information about

performance

• Verify validity by

Comparing results on multiple measures

Multiple time points, multiple raters

40

The 4 Ps (Projects, Performances,

Products, Portfolios)

• Some learning is best measured with an

assessments other than a standardized test

• Yes, they can be used to demonstrate teachers’

contributions to student learning growth

• Here’s the basic approach

Use a high-quality rubric to judge initial knowledge

and skills required for mastery of the standard(s)

Use the same rubric to judge knowledge and skills at

the end of a specific time period (unit, grading period,

semester, year, etc.)

41

Assessing Musical Behaviors: The type of

assessment must match the knowledge or skill

4 types of musical behaviors:

1.Responding

2.Creating

3.Performing

4.Listening

Types of assessment

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Rubrics

Playing tests

Written tests

Practice sheets

Teacher Observation

Portfolios

Peer and SelfAssessment

Slide used with permission of authors Carla Maltas, Ph.D. and Steve

Williams, M.Ed. See reference list for details.

Georgia CLASS KEYS

43

Washington DC IMPACT:

Rubric for Determining Success (for teachers in nontested subjects/grades)

44

Washington DC IMPACT:

Rubric for Determining Success (for teachers in nontested subjects/grades)

45

The “caseload” educators

• For nurses, counselors, librarians and

other professionals who do not have their

own classroom, what counts for you is

your “caseload”

May be all the students in the school

May be a specific set of students

May be other teachers

May be all of the above!

46

Other teachers with “caseloads”

• For team teachers, special ed teachers,

ELL teachers, other itinerant teachers

Caseload would be the students you provide

instruction or assistance to

When students are shared between two

teachers, those students belong to both

teachers’ caseloads

This may be done as a percentage, or the

shared student scores would be counted for

each teacher

47

Tripod Survey (1)

• Harvard’s Tripod Survey – the 7 C’s

– Caring about students (nurturing productive

relationships);

– Controlling behavior (promoting cooperation and

peer support);

– Clarifying ideas and lessons (making success

seem feasible);

– Challenging students to work hard and think hard

(pressing for effort and rigor);

– Captivating students (making learning interesting

and relevant);

– Conferring (eliciting students’ feedback and

respecting their ideas);

– Consolidating (connecting and integrating ideas to

support learning)

48

Tripod Survey (2)

• Improved student performance depends on strengthening

three legs of teaching practice: content, pedagogy, and

relationships

• There are multiple versions: k-2, 3-5, 6-12

• Measures:

student engagement

school climate

home learning conditions

teaching effectiveness

youth culture

family demographics

• Takes 20-30 min

• There are English and Spanish versions

• Comes in paper form or in online version

49

Tripod Survey (3)

• Control is the strongest correlate of value

added gains

• However, it is important to keep in mind

that a good teacher achieves control by

being good on the other dimensions

50

Tripod Survey (4)

• Different combinations of the 7 C's predict different

outcomes (student learning is one outcome)

• Using the data, you can determine what a teacher

needs to focus on to improve important outcomes

• Besides student learning, other important

outcomes include:

happiness

good behavior

healthy responses to social pressures

self-consciousness

engagement/effort

satisfaction

51

Measuring teachers’ contributions to

student learning growth: Rural challenges

• Teachers who are seen as “outsiders” may have

problems building positive relationships with

students and engaging them in learning

Help teacher get connected to community by

assigning a community mentor to help teacher

integrate into local culture

Use place-based learning strategies to engage

students and teachers in discovering local history and

culture while addressing community needs

Provide professional development on “cultural

relativism”

52

Measuring teachers’ contributions to

student learning growth: Frontier Model

• Highly mobile student populations

Assess entering students’ knowledge and

skills as soon as possible

More frequent assessments of students’

progress

Less weight on once-a-year standardized

tests for measuring a teacher’s contribution

since the teacher may have had a limited

opportunity to impact student learning

53

Frontier Model: Assessing student

growth for teacher evaluation

• Mobile student populations

Short-cycle assessments will work better for students

who are highly mobile

• High student absenteeism

Develop specific guidelines for how many total days,

consecutive days, etc. a student must be on a

teacher’s role to “count” for that teachers’ score on

contribution to student learning

• Students who need support

Evaluate teachers’ efforts to address students’

physical, social, and emotional needs

- Evaluate contacts and relationships with parents

54

Frontier Model: Teacher collaboration

• Teachers don’t need to assess in isolation

Collaborate/share great lesson plans, materials,

assessments, etc. across classrooms, schools,

and districts (by content area, grades taught)

Work together to grade projects, essays, etc. by

using technology when meeting in person is not

feasible

- Develop consistency in scoring, ensuring that results

from student assessments are more valid

Webex and other web-based programs allow you

to share files, videos, assessments, and rubrics

55

Frontier Model: Gaining parent

support for teaching and learning

• Support teachers in building relationships

with community and parents

Especially important for teacher retention

Connect them with a community guide/mentor

• Engage community in celebrating student

success

Share student work throughout the year in

community exhibits, performances, etc.

Ask parents to assist in and contribute their

talents and skills to these events

56

Frontier model: District/state support

• Invest in technology and infrastructure that

will enable teachers to connect with each

other and with internet-based resources

• Form regional consortiums to share

resources including personnel

Isolated rural schools may not be able to

afford their own data analysts, curriculum

specialists, etc.

Need a model of sharing personnel across

regions

57

Measures that help teachers grow

• Measures that motivate teachers to examine their own

practice against specific standards

• Measures that allow teachers to participate in or co-construct

the evaluation (such as “evidence binders”)

• Measures that give teachers opportunities to discuss the

results with evaluators, administrators, colleagues, teacher

learning communities, mentors, coaches, etc.

• Measures that are aligned with professional development

offerings

• Measures which include protocols and processes that

teachers can examine and comprehend

58

Results inform professional growth

opportunities

• Are evaluation results discussed with individual

teachers?

• Do teachers collaborate with instructional

managers to develop a plan for improvement

and/or professional growth?

All teachers (even high-scoring ones) have areas

where they can grow and learn

• Are effective teachers provided with opportunities

to develop their leadership potential?

• Are struggling teachers provided with coaches

and given opportunities to observe/be observed?

59

Why you should keep (and provide

support to) the less effective teachers

• With the right instructional strategies and

guidance, motivated teachers can improve

practice and student outcomes

• The teachers you hire to replace your less

effective teachers are not necessarily going to be

more effective

• You may not be able to find better replacements!

• You may not be any to find any replacements!

• The replacements you find may not stay

60

Performance pay for teachers

• Am Assn of School Administrators survey,

52% rural respondents (Ellerson, 2009)

45% expressed moderate-to-strong interest in

pay for performance

20% who don’t support pay for performance

contend that “…good teachers are already

doing the best they can, and performance‐

based pay is highly unlikely to improve their

teaching ability…poor and mediocre teachers

do not become better teacher because more

money is offered.”

61

Performance pay may improve

retention of effective teachers

• Little evidence that pay-for-performance

improves student outcomes, but it does

impact teacher retention in high-poverty,

low-achieving schools (Springer et al., 2009)

• Thus, financial incentives for effective

teachers may work as a signal to them that

they are successful, and successful

teachers are more likely to stay in

placements

62

Evaluating Teacher Preparation

Programs (TPPs)

Evaluate teacher performance

(including student outcomes)

Use results as a measure of TPP

success (for evaluation purposes)

Use results to improve TPP curriculum

and instruction

K-12 Teaching and learning improves

as a result of changes made by TPPs

63

Meeting the “standards”

• It’s possible to be meeting accreditation

standards (NCATE, TEAC) but still not be

preparing fully effective teachers

• If TPPs are not adequately preparing

teachers for the contexts and

communities which they serve, their

effectiveness may be hampered

64

VAMs and Teacher Prep Program

evaluation/assistance

• VAMs may be useful in identifying teacher

preparation programs (TPPs) whose

graduates are not performing at acceptable

levels in terms of student gains

However, VAMs cannot be used to diagnose why

the TPP’s graduates are failing to meet student

progress goals

Additional information should be gathered from the

TPP in order to properly diagnose problems

TPPs can then be provided with guidance and

support to address specific needs

65

TPP Selectivity and Consequences

• TPPs vary in selectivity in the admissions

process

So the quality of candidates is in large part

dependent on the selectivity of the TPP

Unless you “control” for this factor statistically, you

will punish schools that are less selective because

their candidates will likely not perform as well in

their placements

- If, however, you wish to send a signal to TPPs that they

should be more selective, you would not control for

selectivity

66

General Suggestions

• Examine relationships among teachers’ survey

responses and student learning growth

Those correlations may be very useful in driving

subsequent research and discussions about

program effectiveness

• Oversight: Ensure that TPPs are directed to

focus on addressing the issues that teachers

consider most important (survey results)

Classroom management

Differentiating instruction

67

Principal Effectiveness: New Leaders for

New Schools Definition

“New Leaders for New Schools advocates

for an evidence-based, three-pronged

approach to defining principal effectiveness:

1) gains in student achievement, 2)

increasing teacher effectiveness, and 3)

taking effective leadership actions to reach

these outcomes.”

http://www.newleaders.org/wpcontent/uploads/2011/08/principal_effectiveness_nlns_overview.pdf

68

Principal Effectiveness: Center for

American Progress on Principal Evaluation

• Student achievement measures including schoolwide academic

growth, attainment measures of achievement, and cohort graduation

rates

• Recruiting, developing, and retaining effective teachers and effectively

implementing teacher evaluations to improve teacher effectiveness

and/or retain effective teachers at higher rates while reducing the

number of ineffective performers

• Research-based rubrics that assess principals against performance

standards

• Measures of school culture and climate, such as teacher and student

attendance, indicators of school discipline, and parent, student, and

staff perceptions

Summarized from http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2011/03/pdf/principalproposalmemo.pdf

69

Principal Evaluation: Interstate School Leaders

Licensure Consortium (ISLLC) Standards

Standard 1: A school administrator is an educational leader who

promotes the success of all students by facilitating the

development, articulation, implementation, and stewardship of a

vision of learning that is shared and supported by the school

community.

Standards 2: A school administrator is an educational leader who

promotes the success of all students by advocating, nurturing,

and sustaining a school culture and instructional program

conducive to student learning and staff professional growth.

Standard 3: A school administrator is an educational leader who

promotes the success of all students by ensuring management of

the organization, operations, and resources for a safe, efficient,

and effective learning environment.

70

Principal Evaluation: Interstate School Leaders

Licensure Consortium (ISSLC) Standards (cont’d)

Standard 4: A school administrator is an educational leader who

promotes the success of all students by collaborating with families

and community members, responding to diverse community

interests and needs, and mobilizing community resources.

Standard 5: A school administrator is an educational leader who

promotes the success of all students by acting with integrity,

fairness, and in an ethical manner.

Standard 6: A school administrator is an educational leader who

promotes the success of all students by understanding,

responding to, and influencing the larger political, social,

economic, legal, and cultural context.

71

Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education (VAL-Ed)

72

72

Teachers and leaders are the key

• Strong, effective teachers and leaders are the

key to improving student outcomes

• Two ways to get effective teachers and

leaders:

Remove less effective teachers and leaders and

replace them with more effective ones

- Not the preferred option, particularly for isolated

rural or hard-to-staff urban schools

Provide guidance and support to help less

effective teachers and leaders improve

performance

73

Considerations for choosing and

implementing measures

• Consider whether human resources and capacity are

sufficient to ensure fidelity of implementation

• Conserve resources by encouraging districts to join

forces with other districts or regional groups

• Establish a plan to evaluate measures to determine if

they can effectively differentiate among teacher

performance

• Examine correlations among measures

• Evaluate processes and data each year and make

needed adjustments

74

Final thoughts

• The limitations:

There are no perfect measures

There are no perfect models

Changing the culture of evaluation is hard work

• The opportunities:

Evidence can be used to trigger support for struggling

teachers and acknowledge effective ones

Multiple sources of evidence can provide powerful

information to improve teaching and learning

Evidence is more valid than “judgment” and provides

better information for teachers to improve practice

75

Resources and links

• Memphis Professional Development System

Main site: http://www.mcsk12.net/aoti/pd/index.asp

PD Catalog:

http://www.mcsk12.net/aoti/pd/docs/PD%20Catalog%20Spring%20

2011lr.pdf

Individualized Professional Development Resource Book:

http://www.mcsk12.net/aoti/pd/docs/Resource%20guide%201111.pdf

• Harvard’s Tripod Survey

http://www.tripodproject.org/index.php/index/

• National Response to Intervention Center Progress Monitoring

Tools

http://www.rti4success.org/chart/progressMonitoring/progress

monitoringtoolschart.htm

76

Resources and links (cont’d)

• Colorado Content Collaboratives

http://www.cde.state.co.us/ContentCollaboratives/index.asp

• Harvard’s Tripod Survey

http://www.tripodproject.org/index.php/index/

• Louisiana Student Growth for Non-tested Subjects

http://www.louisianaschools.net/compass/sgm_nontested.html

• National Response to Intervention Center Progress Monitoring Tools

http://www.rti4success.org/chart/progressMonitoring/progressmonito

ringtoolschart.htm

• New York State approved teacher and principal practice rubrics

http://usny.nysed.gov/rttt/teachers-leaders/practicerubrics/

• Rhode Island Department of Education Teacher Evaluation –

Student Learning Objectives

http://www.ride.ri.gov/educatorquality/educatorevaluation/SLO.aspx

77

Some “popular” observation

instruments

Charlotte Danielson’s Framework for Teaching

http://www.danielsongroup.org/theframeteach.htm

CLASS

http://www.teachstone.org/

Kim Marshall Rubric

http://www.marshallmemo.com/articles/Kim%20Marshall

%20Teacher%20Eval%20Rubrics%20Jan%

Marzano Teacher Evaluation Framework

http://www.marzanoevaluation.com/

78

Growth Models

American Institutes of Research (AIR)

http://www.air.org/

Colorado Growth Model

www.nciea.org

Mathematica

http://www.mathematicampr.com/education/value_added.asp

SAS Education Value-Added Assessment System (EVAAS)

http://www.sas.com/govedu/edu/k12/evaas/index.html

Wisconsin’s Value-Added Research Center (VARC)

http://varc.wceruw.org/

79

Educator Evaluation Systems

• Austin (TX) Teacher and Principal Evaluation

http://archive.austinisd.org/inside/initiatives/compensation/evaluation.p

html

• Colorado Educator Effectiveness

http://www.cde.state.co.us/EducatorEffectiveness/index.asp

• Montgomery County (MD) Public Schools

http://www.montgomeryschoolsmd.org/departments/development/doc

uments/TeacherPGS_handbook.pdf

• Rhode Island Teacher Evaluation

http://www.ride.ri.gov/educatorquality/educatorevaluation/Default.aspx

• Tennessee Teacher Evaluation http://team-tn.org/

• Washington DC Impact Evaluation

http://www.dc.gov/DCPS/In+the+Classroom/Ensuring+Teacher+Succe

ss/IMPACT+(Performance+Assessment)/IMPACT+Guidebooks

80

Principal Evaluation Instruments

Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education

http://www.valed.com/

• Also see the VAL-Ed Powerpoint at

http://peabody.vanderbilt.edu/Documents/pdf/LSI/VALED_AssessLCL.p

pt

North Carolina School Executive Evaluation Rubric

http://www.ncpublicschools.org/profdev/training/principal/

• Also see the NC “process” document at

http://www.ncpublicschools.org/docs/profdev/training/principal/principalevaluation.pdf

Iowa’s Principal Leadership Performance Review

http://www.sai-iowa.org/principaleval

Ohio’s Leadership Development Framework

http://www.ohioleadership.org/pdf/OLAC_Framework.pdf

81

References

Anderson, L. (1991). Increasing teacher effectiveness. Paris: UNESCO, International Institute for Educational Planning.

Betebenner, D. W. (2008). A primer on student growth percentiles. Dover, NH: National Center for the

Improvement of Educational Assessment (NCIEA).

http://www.cde.state.co.us/cdedocs/Research/PDF/Aprimeronstudentgrowthpercentiles.pdf

Braun, H., Chudowsky, N., & Koenig, J. A. (2010). Getting value out of value-added: Report of a

workshop. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=12820

Ellerson, N. M. (2009). Exploring the possibility and potential for pay for performance in America’s

public schools. Washington, DC: American Association of School Administrators.

Finn, Chester. (July 12, 2010). Blog response to topic “Defining Effective Teachers.” National Journal

Expert Blogs: Education.

http://education.nationaljournal.com/2010/07/defining-effective-teachers.php

Fuller, E., & Young, M. D. (2009). Tenure and retention of newly hired principals in Texas. Austin, TX:

Texas High School Project Leadership Initiative.

http://www.ucea.org/storage/principal/IB%201_Principal%20Tenure%20and%20Retention%20in%20T

exas%20of%20Newly%20Hired%20Principals_10_8_09.pdf

82

References (cont’d)

Glazerman, S., Goldhaber, D., Loeb, S., Raudenbush, S., Staiger, D. O., & Whitehurst, G. J. (2011).

Passing muster: Evaluating evaluation systems. Washington, DC: Brown Center on Education

Policy at Brookings.

http://www.brookings.edu/reports/2011/0426_evaluating_teachers.aspx#

Goe, L. (2007). The link between teacher quality and student outcomes: A research synthesis.

Washington, DC: National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality.

http://www.tqsource.org/publications/LinkBetweenTQandStudentOutcomes.pdf

Goe, L., Bell, C., & Little, O. (2008). Approaches to evaluating teacher effectiveness: A research

synthesis. Washington, DC: National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality.

http://www.tqsource.org/publications/EvaluatingTeachEffectiveness.pdf

Goe, L., Holdheide, L., & Miller, T. (2011). A practical guide to designing comprehensive teacher

evaluation systems Washington, DC: National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality.

http://www.tqsource.org/practicalGuide

Hassel, B. (Oct 30, 2009). How should states define teacher effectiveness? Presentation at the

Center for American Progress, Washington, DC.

http://www.publicimpact.com/component/content/article/70-evaluate-teacher-leader-performance/210how-should-states-define-teacher-effectiveness

83

83

References (cont’d)

Herman, J. L., Heritage, M., & Goldschmidt, P. (2011). Developing and selecting measures of student

growth for use in teacher evaluation. Los Angeles, CA: University of California, National Center for

Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST).

http://www.cse.ucla.edu/products/policy/shortTermGrowthMeasures_v6.pdf

Hill, H. C., Charalambous, C. Y., & Kraft, M. A. (2012). When rater reliability is not enough: Teacher

observation systems and a case for the generalizability study. Educational Researcher, 41(2), 56-64.

http://edr.sagepub.com/content/41/2/56.full?ijkey=h774H07DfsQ4E&keytype=ref&siteid=spedr

Howes, C., Burchinal, M., Pianta, R., Bryant, D., Early, D., Clifford, R., et al. (2008). Ready to learn?

Children's pre-academic achievement in pre-kindergarten programs. Early Childhood Research

Quarterly, 23(1), 27-50.

http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/detail?accno=EJ783140

Hunt, B. C. (2009). Teacher effectiveness: A review of the international literature and its relevance for

improving education in Latin America. Washington, DC: Partnership for Educational Revitalization in

the Americas (PREAL).

http://preal.org/Archivos/Bajar.asp?Carpeta=Preal Working Papers&Archivo=Teacher Effectivenes.pdf

Kane, T. J., Taylor, E. S., Tyler, J. H., & Wooten, A. L. (2010). Identifying effective classroom practices using

student achievement data. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

http://www.nber.org/papers/w15803

84

References (cont’d)

Koedel, C., & Betts, J. R. (2009). Does student sorting invalidate value-added models of teacher

effectiveness? An extended analysis of the Rothstein critique. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of

Economic Research.

http://economics.missouri.edu/working-papers/2009/WP0902_koedel.pdf

McCaffrey, D., SasLinn, R., Bond, L., Darling-Hammond, L., Harris, D., Hess, F., & Shulman, L. (2011).

Student learning, student achievement: How do teachers measure up? Arlington, VA: National

Board for Professional Teaching Standards.

http://www.nbpts.org/index.cfm?t=downloader.cfm&id=1305

Lockwood, J. R., & Mihaly, K. (2009). The intertemporal stability of teacher effect estimates. Education

Finance and Policy, 4(4), 572-606.

http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/edfp.2009.4.4.572

Pianta, R. C., Belsky, J., Houts, R., & Morrison, F. (2007). Opportunities to learn in America’s

elementary classrooms. [Education Forum]. Science, 315, 1795-1796.

http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/summary/315/5820/1795

Prince, C. D., Schuermann, P. J., Guthrie, J. W., Witham, P. J., Milanowski, A. T., & Thorn, C. A.

(2006). The other 69 percent: Fairly rewarding the performance of teachers of non-tested subjects

and grades. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Elementary and Secondary

Education.

http://www.cecr.ed.gov/guides/other69Percent.pdf

85

References (cont’d)

Race to the Top Application

http://www2.ed.gov/programs/racetothetop/resources.html

Sartain, L., Stoelinga, S. R., & Krone, E. (2010). Rethinking teacher evaluation: Findings from the first

year of the Excellence in Teacher Project in Chicago public schools. Chicago, IL: Consortium on

Chicago Public Schools Research at the University of Chicago.

http://ccsr.uchicago.edu/publications/Teacher%20Eval%20Final.pdf

Schochet, P. Z., & Chiang, H. S. (2010). Error rates in measuring teacher and school performance

based on student test score gains. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and

Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/pubs/20104004/pdf/20104004.pdf

Springer, M., Lewis, J. L., Podgursky, M. J., Ehlert, M. W., Taylor, L. L., Lopez, O. S., et al. (2009).

Governor’s Educator Excellence Grant (GEEG) Program: Year three evaluation report (Policy

Evaluation Report). Nashville, TN: National Center on Performance Incentives.

http://ritter.tea.state.tx.us/opge/progeval/TeacherIncentive/GEEG_Y3_0809.pdf

Redding, S., Langdon, J., Meyer, J., & Sheley, P. (2004). The effects of comprehensive parent

engagement on student learning outcomes. Paper presented at the American Educational

Research Association

http://www.adi.org/solidfoundation/resources/Harvard.pdf

U.S. Department of Education (2012). ESEA Waiver Application (revised February 10, 2012).

http://www.ed.gov/esea/flexibility/documents/esea-flexibility-request.doc

86

References (cont’d)

Rivkin, S. G., Hanushek, E. A., & Kain, J. F. (2005). Teachers, schools, and academic achievement.

Econometrica, 73(2), 417 - 458.

http://www.econ.ucsb.edu/~jon/Econ230C/HanushekRivkin.pdf

Weisberg, D., Sexton, S., Mulhern, J., & Keeling, D. (2009). The widget effect: Our national failure to

acknowledge and act on differences in teacher effectiveness. Brooklyn, NY: The New Teacher

Project.

http://widgeteffect.org/downloads/TheWidgetEffect.pdf

Yoon, K. S., Duncan, T., Lee, S. W.-Y., Scarloss, B., & Shapley, K. L. (2007). Reviewing the evidence

on how teacher professional development affects student achievement (No. REL 2007-No. 033).

Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center

for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Southwest.

http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/regions/southwest/pdf/REL_2007033.pdf

87

Questions?

88

Laura Goe, Ph.D.

609-619-1648

lgoe@ets.org

www.lauragoe.com

https://twitter.com/GoeLaura

National Comprehensive Center for

Teacher Quality

1000 Thomas Jefferson Street, NW

Washington, D.C. 20007

www.tqsource.org

89