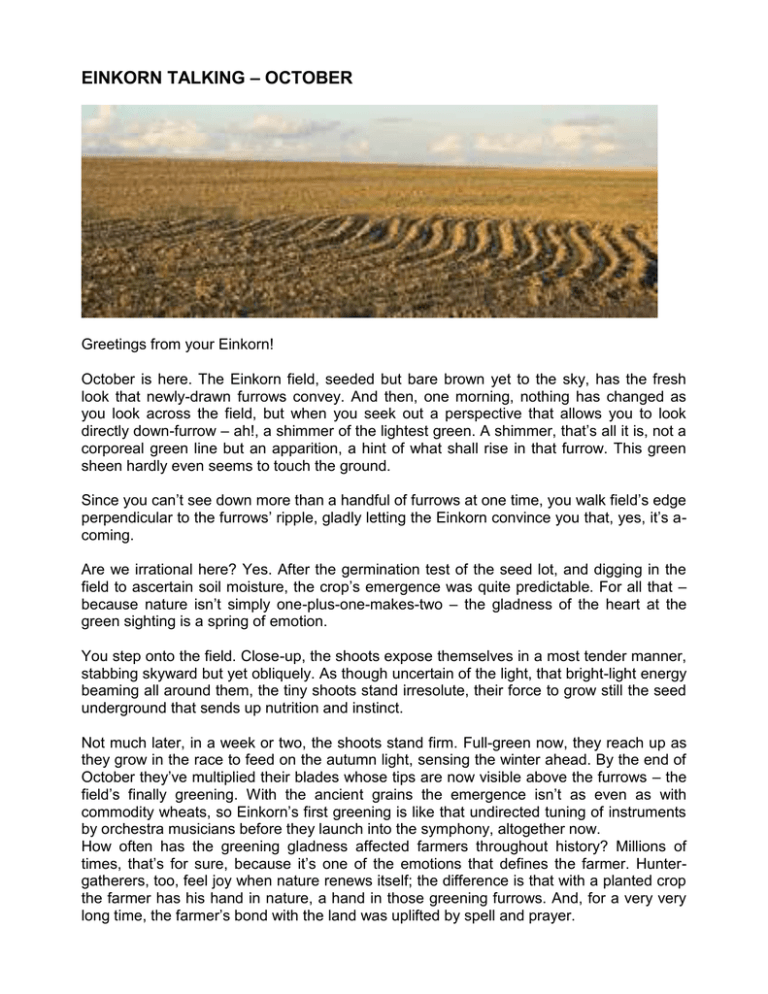

einkorn talking – october

advertisement