Handout 1: Overview of Impact Assessment

advertisement

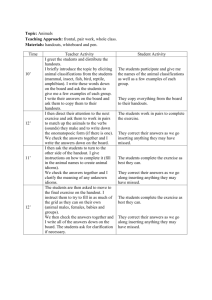

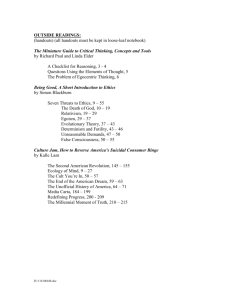

Impact assessment Training 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Handout 1: Overview of Impact Assessment Definitions: Impact Assessment can be defined as “the systematic analysis of significant and/or lasting change – positive or negative, intended or not – in the lives of target groups, brought about by a given action or a series of actions”. The guidelines are designed to enable you to carry out this systematic analysis. Impact Assessment – So What? Impact assessment is designed to ask (and answer) the “SO WHAT” questions: we have completed our project/programme successfully: So what has actually changed? For whom? How significant have these changes been for different target groups? How did these changes come about? What are the factors contributing to them? What, if anything, did our programme contribute to these changes? So what should we do differently next time? Purpose: The overall goal for all those of us who work in development should be to improve the quality of life for those men, women, girls and boys in the communities where we are work. The most important reason therefore, for assessing the impact of our efforts is to learn about what works, what difference are we making and to continually try to improve our effectiveness. Additionally, we need to be able to report on impact for our donors (although donors mostly only focus on outcomes or, at best, expected impacts in relation to log frames). We are accountable to all of our stakeholders, especially the communities with whom we work : we should be working together with them to identify changes that they want to see in their lives; and to monitor and assess how well our projects and programmes are contributing to these identified changes Lastly, but not least, evidence of impact is a very powerful tool for advocacy (for example, evidence of numbers of children whose lives have improved as a result of a change of law or policy); and for inspiration. Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 2 Handout 2: Some Key Challenges to Assessing Impact While many organisations have successfully developed processes to monitor and evaluate their projects and programmes (at the level of outputs and outcomes), the majority fail to look beyond their individual projects or programmes to really assess the difference they are making in people’s lives. They struggle to assess the impact that their efforts have on target communities, individuals or environments. Reasons for this include: 1. Lack of organisational clarity about the differences between M&E and impact. 2. Development organisations often work through partners. They then struggle to understand the scope of their influence and the levels at which they can realistically assess impact (and what their partners should be assessing). 3. Attributing evidence of change to specific interventions is challenging, if not impossible. 4. The design of the impact assessments is too complex; or it attempts to address too many needs. 5. Identifying useful starting points from which to assess impact, including baseline data and deciding which indicators to work with. 6. There are so many tools and processes available that designers of impact assessments overly complicate the process; and/or require staff and partners to work with tools that they are unfamiliar with. 7. Honest impact assessments are hard to find. Its very hard to tell the truth if it will negatively affect chances of funding, or if it threatens relationships in any way. 8. Impact assessment findings are not used creatively or effectively, so their value is not always recognised Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 3 Handout 3: Relationship with Monitoring and Evaluation Monitoring and evaluation focus directly on the progress and effectiveness of projects and programmes, while impact assessment focuses on change. They are different but complementary processes. Each has a different purpose in relation to our work, and all are necessary. This is summarized in the chart below: Monitoring Evaluation Impact Assessment Measures on-going activities Measures performance against objectives Assesses change in people’s lives: positive or negative, intended or not Main work during implementation Main work in middle or at end of project/programme cycle Can be included at all stages and/or can be used specifically after the end of programme/project Focus on interventions Focus on interventions Focus on affected populations Focus on outputs Focus on outcomes/impact Focus on impact and change What has happened? Did we achieve what we set out to achieve? What has changed? For whom? How significant is it for them? Will it last? What, if anything, did our programme contribute? What is being done? Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 4 Handout 4: Theories of Change and Dimensions (or Domains) of Change: WHAT IS A THEORY OF CHANGE? - - - A coherent connection between a system’s mission, strategies and actual outcomes, and articulated links between those who are being served, the strategies or activities that are being implemented, and the planned outcomes A clear and testable hypothesis about how change will occur that not only allows implementers to be accountable for results, but also makes these results more credible because they were predicted to occur in a certain way An agreement among stakeholders about what defines success and what it takes to get there A framework for impact assessment with dimensions of change and a menu for indicators to explore A powerful communication tool to capture the complexity of the project initiative Note: Theories of Change can be set at Organisational levels or Programme levels. For YCI we plan to set them at organisational level WHAT’S INCLUDED IN A THEORY OF CHANGE? Four clearly articulated components: - Component 1: A conceptual piece considering how change happens in relation to target groups and issues that relate to your organisational mission and mandate - Component 2: An Organisational Change Pathway which includes an articulation of: The problem(s) to be addressed; and their underlying causes A vision of change you (your org/project) wants to effect Populations: who you are serving. Principles of Engagement Strategies: what strategies you believe will accomplish desired changes Outcomes: what you intend to achieve which will lead to these changes Contribution to your organisational goal And the relationship between all of these core elements - Component 3: An Impact Assessment Framework based on the components above – often framed as “Dimensions of Change” - Component 4: A process of critical reflection to test assumptions that were made and revise the original theory Note: Different organisations have opted to complete some or all of these components in relation to their Theories of Change DIFFERENCES BETWEEN TOC AND OTHER LOGIC MODELS: - It shows a causal pathway by specifying what is needed for goals to be achieved Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 5 - - It requires the articulation of underlying assumptions which can be tested and measured. It changes the way of thinking about implementation strategies: the focus is not so much on what is being done, but rather what needs to be changed. The logical framework should be guided by and developed as a result of the Theory of Change ( they are not mutually exclusive) Logic Models Theories of Change Representation List of Components Descriptive Critical Thinking Pathway of Change Explanatory WHY DEVELOP A TOC? - For more effective planning To improve and assure accountability To be more targeted in resource allocation To communicate and market development strategies To make direct links to action IT CAN BE USED: - As a framework to check progress towards change (to complement project logic) and to stay on course To be able to test the weak links ion the change pathway (right people? right strategies? Right outcomes?) To document lessons learned about what really changes in relation to our efforts To keep the process of implementation, and impact assessment transparent, so everyone knows what changing and how As a basis for reports to funders, policymakers, boards WHAT DO THEY LOOK LIKE - Usually they are 2-5 pages in length with a short narrative followed by a diagram. Some look like flow charts Some diagrams look like flow charts Some are much more elaborate What they must so is illustrate your organizational (or programme) pathway to change HOW TO DEVELOP A THEORY OF CHANGE - Developing a Theory of Change must involve all key stakeholders The idea and the process needs buy-in from Senior Management Usually it is wise to hire a facilitator to help you (the organization or programme) through the process of designing a process that suits your needs. With the facilitator, you will decide what research needs carrying out; and what needs to be agreed; and what needs to be so Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 6 - You will carry out the research and relevant tasks, and then probably call the facilitator back in to complete and to be assured that all parts are in order and that you have an effective plan in place for ensuring that the ToC will be useful to and used in the future. Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 7 Draft Domains of Change Framework for Education (BEP) Outcomes Outcomes Children participate in decisions that affect their education Policy and regulation ensures quality education that is affordable and accessible for all children Parents and guardians support the education of all children, especially girls and marginalised children Communities, including children are involved in supporting and influencing school policy and development Community and civil society organisations are involved in operating and managing schools Outcomes 6 Changes in ways local communities influence educational policy and contribute to the provision of education Improved enrolment rates, especially for girls and marginalised children Improved attendance and completion rates especially for girls and marginalized children All children and young people acquire socially and economically relevant skills as a result of their educational opportunities Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 5 Changes in enrolment and completion of education for all children, especially girls and marginalised children Outcomes Adequate resources are allocated for the provision of quality education for all Budgets are used effectively for the implementation of policies (incl. teacher pay, text books, etc) 2 Changes in the provision of quality education by Governments and other mandated bodies Schools are accessible and available to all children All children feel safe on the way to school and within school environments Schools are effectively managed Facilities and resources offered within the school support effective learning 1 Changes is the ability of all children and young people to access quality education which results in relevant and useful learning for them 3 Changes in the relevance and availability of educational infrastructure and institutional development Outcomes School and educational curricula are relevant and appropriate Student assessment systems and processes are appropriate and equitable 4 Changes in the quality and relevance of educational curricula, teaching standards and assessment methodologies Handouts Page 8 Teaching force delivers the curriculum effectively Teachers’ pay and conditions enable them to carry out their duties Handout 5: Spheres of Influence Organisations working through national or local partner organisations can’t attribute their efforts to changes at community level So they struggle to understand • what they should be assessing in terms of impact • what their partners should be assessing • the relationship between these different areas. One way to address this challenge is to work out what changes can realistically be linked to your organisational efforts: consider and agree what areas of changes might link directly to your efforts; and what areas of change may be indirectly linked to your efforts. This can be reflected in your Dimensions of Change Example from CDKN: CDKN works primarily to influence changes in the outer boxes but contributes to changes in the outer and inner rings Slide 15 Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 9 Handout 6: Handout Different approaches to Impact Assessment Three broad, and sometimes overlapping, approaches are often used to assess impact: The first approach is likely to include be a retrospective study of a project which has, typically, been planned using a linear approach to change (as developed through logical framework analysis for example). More often than not, this assessment involves the use of an external (or partly external) team who carries out the assessment at a fixed point after the completing of the project. The main purpose of this approach is to test or verify whether the logic of the project) was correct: did it achieve the changes that it set out to achieve? The second approach is more process driven - and less judgmental - than the first. Stakeholders are involved in all stages of the project or programme cycle: in the design and the development of the project or programme, they are included in identifying the changes that they would like to see in their lives; during the implementation phase, they influence the direction the project takes. They are included in the monitoring and evaluation, at the impact assessment stage, they inform the process identifying the changes that have taken place in their lives as a result of the project or programme. This type of assessment is clearly empowering for stakeholders; and it makes valuable contributions to organisational learning. The third approach is somewhat different from the first two. It is a study that takes place some years after the completion of the project or programme and it sets out firstly to identify changes that have taken place within the community, and secondly, to what extent they can be attributed to particular interventions. The purpose of this type of assessment is to understand to what extent organisational efforts are making a difference to the lives of the people they claim to be working with and for. Although this type of assessment is more complex and time consuming, it is one that all organisations need to consider carrying out from time to time. All three approaches – and variations on them - have their own validity in relation to the main purpose of assessing impact. Often, a combination of elements of all three approaches will be necessary in order to understand both planned and unplanned changes. Different Strategies for Assessing Impact: The approach to impact assessment is very connected to the purpose for carrying it out. Impact Assessment is best carried out if a number of strategies are used. For example, some or all of the following could be used to assess the impact of a programme: a. Build ongoing monitoring of impact into M&E reporting formats. Impact data will then be gathered routinely alongside other M&E data. b. At certain points of the programme, build in time for critical reflection (“so what has changed so far in relation to our efforts? For whom? How significant is this? How should we adapt our programme as a result?”). This can be done at any time or specifically as part of the mid-term review and evaluation process c. Carry out one or more tracking study through the life of a programme. This will provide information about how identified sample groups are changing and developing as a result of on-going programme efforts. d. Ensure that a retrospective study takes place sometime after the completion of the programme. This will assess the changes that have occurred in relation to the programme, and to what extent it was able to contribute to these changes. Key tips: Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 10 The assessment of impact can be carried out relatively easily and cheaply. If it is done well, it can be really rewarding and motivating for all concerned. Two key tips: Ensure that they are useful, user friendly and that they build on existing structures and systems Ensure that conditions for assessing impact enable people to be involved and be as honest as possible. This means investing in time and building the trust of those with whom you are working. If people believe that you are trying to understand change in order to improve (rather than to judge success or failure), they are more likely to give honest answers. Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 11 Handout 7: Case Study Task You will be working in small groups on designing an impact assessment process for a specific thematic area or set of interventions. You will be asked to complete this task in stages through the course of the day. You will present a summary of your answers to the whole group tomorrow morning. Please document your answers either on flip chart or on PowerPoint. Note: Your aim should be to develop a process that is: Simple and user- friendly Builds on existing structures and systems Is useful for your organisational learning Before you start: Agree on case study framework: • • • • • Brief profile of org ( size, mandate, scope of activity and areas of work) Direct Interventions or working through partners? Reason for conducting an impact assessment Programme Goal Three outcomes Case Study Task 1: Designing the impact assessment What will be the main purpose of doing this impact assessment? Organisational learning? To meet donor demands? Accountability to stakeholders? For advocacy Which approach (or combination of approaches?) to Impact Assessment would be most appropriate in this Why? What will be the scope and scale of this assessment? Case Study Task 2: Develop/confirm theory of change and/or dimensions of change and areas of enquiry What is your realistic “scope of influence”? Which what areas of impact will you realistically be able to “assess”, and which areas of change will you be able to “illustrate contributions to change”? Based on this,what “Dimensions of Change” will you be looking to assess? Develop a menu of areas of enquiry which will enable you to set baselines and track progress in relation to impact Case Study Task 3: Select methods for gathering relevant information Propose a range of appropriate methods that you could use to gather relevant data for both monitoring and assessing impact (including building on or adapting existing tools and mechanisms). Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 12 Handout 8: Developing Areas of Enquiry to explore Medium and Long Term Change Areas of enquiry are written in neutral language to allow for the reporting of unintended and unexpected changes as well as those that were intended and positive.They are directly linked to Dimensions of Change and specific medium and long term changes that the project/programme hopes to achieve. Areas of enquiry are likely to vary across regions, nations and sectors. It is essential that the indicators are relevant to specific situations E.g. using changes in awareness and mobilisation of key stakeholders (in relation to child labour). Dimension: Changes in frequency and content of CL issues discussed in public arenas and on political agendas Dimension Changes in awareness and attitudes of key stakeholders Dimension Changes in the extent and type of Community involvement around CL issues Possible Areas of Enquiry The extent to which leaders and other respected people are seen to be championing CL The ways in which the media – TV, radio, electronic (blogs), newspapers etc – covers CL issues Numbers and types of civil society campaigns on CL issues How and when CL appears in other public forums The extent to which CL issues are included in school curricula The extent to which universities take an interest in CL Possible Areas of Enquiry Shift in awareness, knowledge, attitudes and commitment in respect of CL among the general public and key multiplier groups in particular e.g. influencers and decisionmakers. Tools/ Sources of Information Interview/group discussions s with stakeholders and documentary review. Possibly network analysis. Media monitoring over an extended period Interviews/group discussions with stakeholders and documentary review Public record Interviews with educators Sources of information KAP-type surveys preferably linked to baseline information relating to changes. If no pre-survey, sample of depth interviews/group discussions to probe further the extent of change and the stimuli for the changes. Sources of information Interviews/group discussions with stakeholders Possible Areas of Enquiry Shifts in levels of Community mobilisation around CL - e.g. CL committees set up and operational Levels and types of actions taken by Participative enquiry and communities taking effective action e.g. self- interviews. sensitizing, monitoring, reporting, self enforcing/regulating where appropriate, referring vulnerable children and households to agencies Levels of mobilisation against CL in schools Ways in which children and households acquire social and psychological coping mechanisms Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 13 Handout 9: Example of a Success Scale - Advocacy Programme Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 14 Handout 10: Setting Baselines for Impact Monitoring and Assessment Why have a baseline? The purpose of impact monitoring and assessment is to involve programme leaders and managers and key stakeholders in a coherent process of understanding and recording the changes that are taking place in relation to their organisational or programme efforts. This information will enable them to: understand how and to what extent programmes are contributing to change objectives identifies in relation to organisational Dimensions of Change; communicate success and understand where (and why) particular programmes are failing to achieve their planned impact; and adapt or adjust programmes and projects in order to achieve greater positive impact. How should the baseline be developed? Baselines will be characterised by the following guiding principles. The methodology should be flexible. Baselines will be tailored for each programme depending on the strength of existing relationships, knowledge and capacity. Baselines, and subsequent impact monitoring, will be designed to capture lessons learned and incorporate these into future methodologies. Baselines will be “light-touch” in character. The emphasis will be on analysis. They will form an intelligent interpretative view of where the programme stands in relation to relevant dimensions of change, as well as the programme change objectives and indicators. Baselines should not be a heavy resource intensive or expensive exercise. Baselines should build on or draw from other diagnostic processes, (for example situation analyses which inform programme design). They should not duplicate other processes. They should be developed and written in the most useful language for the programme, but may also need to be translated into English for purposes of global reporting. What information should be covered by the baseline? The baseline will basically provide information on the current situation, so that changes at a later date can be assessed against that situation. The precise nature of the information to be collected will depend on the type of programme, whether or not it is time bound, how far desired changes can be accurately predicted, and the scale of resources dedicated to the programme. The following should be considered: All programmes should develop a degree of baseline information against relevant dimensions of change If there are specific change objectives associated with the programme then the baseline should attempt to show the current situation regarding those particular change objectives. Who should be involved in collecting baseline information? Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 15 The programme leader and programme managers should collect the information in collaboration, where possible, with key stakeholders. This can be a large or small exercise depending on the size and duration of the programme. Where there is a programme or country engagement leader, s/he would be expected to coordinate this role. However, key partners, stakeholders, and/or different target groups should also be represented wherever possible. How should information be collected? The process for data collection will vary according to need, on a case-by-case basis. It might also vary according to the type of tools and methodologies used to access the data. At its most basic, it might include a desk exercise which is informed by a few key interviews. It might also involve a dedicated workshop for key stakeholders and representation from target groups. At the other end of the scale, it could involve a more strategic and holistic planning process When should it be collected? Often baseline information proves to be a strenuous time consuming exercise which turns out to be of little use for impact monitoring. This is because the exercise was carried out too early - before the programme implementation strategy had been clearly defined and articulated. In order for it to be useful as a basis for collecting impact monitoring information, the programme needs clarity on its priority dimensions of change and its implementation strategy for each of these dimensions. It is therefore recommended that the baseline information gathering process is carried out as an integral part of the programme planning process. Under some circumstances, this may mean it is carried out some months into the programme. Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 16 Handout 11: Criteria for Selecting Tools The following criteria may be useful in assisting staff to select appropriate tools for differing impact assessment needs. It is important to stress that tools are only useful if they are used intelligently! Outcome or impact: To what extent does the tool seek to study impact, and not only outcomes? Measurement (Quantitative Data): How far does the tool allow for quantitative analysis of change? Description: How far does the tool allow for qualitative analysis of change? Attribution of change: How well does the tool deal with attribution of change and the exploration of cause-effect-relationships? Baselines: To what extent does the tool cope without the existence of baseline data? Use of Indicators; How far does the tool cope without the existence of pre-determined indicators? "Proving", giving evidence for accountability: To what extent does the tool seek to provide evidence of change? "Improving", promoting critical reflection: To what extent does the tool promote critical reflection among participants? Local participation: To what extent does the tool explicitly take a participatory and empowering approach that includes the people intended as ‘beneficiaries’? Aggregation: To what extent does the tool allow for aggregation of outcomes or impacts (across groups affected by an intervention, e.g. geographically, or at an organisational level)? Disaggregation: To what extent does the tool support differentiated analysis of change among different groups affected, e.g. socio-economic, ethnic, cultural groups? Gender disaggregation: To what extent does the tool specifically support differentiated analysis of change by men, women, boys and girls? Use by implementing staff: How appropriate is the tool for direct use by front-line implementing staff? Use by communities: How appropriate is the tool for direct use by communities? How appropriate is the tool for direct use by people with limited literacy? Transparency and feedback: To what extent does the tool incorporate feedback on findings to implementing staff and those being assessed? Sector coverage: To what extent is the tool applicable across more than one sector? Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 17 Handout 12: Some Key Data Collecting Methods and their Strengths and Weaknesses (Source: INTRAC) Method Definition and Use Case Studies Collecting information that results in a story that can be descriptive or explanatory and can serve to answer questions of how and why Strengths Weaknesses Can deal with a full variety of evidence from documents, interviews, observation Can add explanatory power when focus is on institutions, processes, programmes, decisions and events Good case studies are difficult to do Require specialised research and writing skills to be rigorous Can’t generalise findings to population Time consuming Difficult to replicate Focus Groups Interviews Holding focused discussions with members of target population who are familiar with pertinent issues before writing a set of structured questions. The purpose is to compare the beneficiaries’ perspectives with abstract concepts in the evaluation’s objectives Similar advantages to interviews Can be expensive and time consuming Particularly useful where participant interaction is desired Must be sensitive to mixing of hierarchical levels Useful way of identifying hierarchical influences Can’t make gereralisations The interviewer asks questions of one or more persons and records the respondents’ answers. Interviews may be formal or informal, face-to-face or by telephone, or closed- or open ended. People and institutions can explain their experiences in their own words and setting Time consuming Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Flexible to allow the interviewer to pursue unanticipated lines of enquiry or to probe Handouts Page 18 Can be expensive If not done properly, the interviewer can They can be structured, semi-structured or – rarely – unstructured influence the interviewee’s response issues in depth Particularly useful where language difficulties are anticipated Greater likelihood of getting input from senior officials Observation Questionnaires Observing and recording situation in a log or Provides descriptive information on context diary. This includes who is involved; what and observed changes happens; when, where, and how events occur. Observation can be direct (observer watches and records), or participatory (observer becomes part of the setting for a period of time). Quality and usefulness of data highly dependent on observer’s observational; and writing skills Developing a set of survey questions whose answers can be coded consistently The quality of responses highly dependent on the clarity of questions Can reach a wide sample simultaneously Allows respondents time to think before they answer Can be answered anonymously Impose uniformity by asking all respondents the same things Findings can be open to interpretation Does not easily apply within a short time-frame to process change Sometimes difficult to persuade people to complete and return questionnaire Can involve forcing institutional activities and people’s experiences into predetermined categories Make data compilation and comparison easier Written Reviewing documents such as records, administrative databases, training materials Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Can identify issues to investigate further and provide evidence of action, change and impact Handouts Page 19 Can be time consuming Document Analysis Stories of Change KAB/P studies Media monitoring and correspondence to support respondents’ perceptions Can be inexpensive These are similar to case studies but with a greater focus on change. They are many variations. MSC is a specific process that mobilises small groups involved with interventions in the regular capturing of outcome stories. (Davies, Dart 2005) Very good for capturing significant, unexpected , positive and or negative changes Time consuming in preparation, implementation and analysis Very participatory Not useful for collecting quantitative data A KAB/P survey is a method of obtaining largely quantitative data relating to people’s awareness, knowledge, attitudes, behaviour, practices or some other aspect of their lives. It is usually a sample survey using a structured questionnaire. It can be administered directly face-to-face or by telephone, or through self-completion via the internet or physical documents. KAB/P surveys can be used longitudinally to collect baseline data and capture changes without relying on interviewees’ recall Time consuming in preparation, implementation and analysis Media monitoring encompasses a range of processes for tracking the appearance in the media of matters of interest (e.g. child labour issues). This is typically outsourced to an agency and is increasingly employs electronic search technology. Very useful for tracking change in relation to advocacy efforts as change is notoriously unpredictable Cost implications if outsourced. Is only useful if high levels of analysis applied Participatory approaches encompass a range of methodologies which ensure that Particularly appropriate in working with groups for whom questionnaires or conventional FGDs Not so good for capturing information when number of stakeholders is very Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Very good for tracking and assessing changes in capacity Handouts Page 20 PRA techniques that the perspectives and insights of all stakeholders, beneficiaries as well as project implementers, are taken into consideration in the design and conduct of evaluative research Examples include risk maps, time lines, scoring and ranking exercises Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 are less appropriate. They encourage people to describe aspects of their lives and changes brought about by interventions in their own terms. Can be used to convert qualitative data into quantitative information Handouts Page 21 high Time consuming and requires skilled facilitators Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 22 Handout 13: A word on RCTs: Definition of Randomised controlled Trial (RCT) - Medinet Randomized controlled trial: (RCT) a study in which people is allocated at random (by chance alone) to receive one of several clinical interventions. One of these interventions is the standard of comparison or control. The control may be a standard practice, a placebo ("sugar pill"), or no intervention at all. Someone who takes part in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) is called a participant or subject. RCTs seek to measure and compare the outcomes after the participants receive the interventions. Because the outcomes are measured, RCTs are quantitative studies. In sum, RCTs are quantitative, comparative, controlled experiments in which investigators study two or more interventions in a series of individuals who receive them in random order. The RCT is one of the simplest and most powerful tools in clinical research. In relation to Development In recent years there has been a lively debate in impact assessment about the circumstances in which it is possible to attribute changes to interventions – to demonstrate causality. This debate has highlighted the role of experimental – or quasi-experimental methodologies in impact assessment. These methodologies use a control group – a “counterfactual”1 - which is identified in advance and does not have any contact with the or project. What is more, in the most pure version of the methodology, programme targets – usually people - are assigned at random between the control group and the group that receives the intervention, so as to avoid selection bias. These methodologies in their pure form are usually referred to as Randomised Control Trials or RCTs. Experimental methodologies work best in simple, short-term, single-variable, interventions. In these contexts it may possible to attribute changes to the intervention. Interventions typical of the enabling environment (e.g. capacity building, governance, participation, and advocacy) are usually complex, long-term and multi-variable. These are usually not susceptible to experimental methodologies such as RCTs because the links between the interventions and the changes cannot be proven statistically. However it is possible to demonstrate a contribution or credible association 2 between the interventions and the changes that the impact assessment identifies using other methodologies. These include • Identifying the intervention logic. Capturing data from a sufficient number of different sources, both quantitatively and qualitatively, to enable “triangulation”. Triangulation reduces the chance of bias in any particular data source. Establishing plausible connections between the interventions and the changes identified. Exploring other explanations for the changes with an open mind before eliminating them. A “counterfactual” is a situation - e.g. the status or condition of a group of people - that exists independent of the programme. Control groups are the most commonly used counterfactuals in impact assessment and evaluation 1 Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 23 The most important way of shining a light on the connection between the interventions and the changes that are observed is a systematic impact assessment design process, and in particular the establishment of the underlying intervention logic or Theory of Change Harry Jones, ODI, comments on some of the problems associated with RCTs: RCTs tend to be carried out where they are methodologically convenient rather than where the new knowledge is really needed. There is massive publication bias, by our count over 95% of published RCTs show ‘positive’ impact, which severely limits the ability to really learn The key problem is about the relationships between RCTs and policy. RCTs were hugely fashionable in the US in the ’60s until it was clear that they couldn’t deliver all that was hoped. Now, it seems that development policy makers are in love with the idea of having clear numbers on the impact of all of their work. The problems include: • • • • Policy makers often assume a much higher level of external validity than is actually appropriate, and tend to ignore the careful caveats which come along with RCTs The RCT model is only suitable for measuring impact in a subset, nay a minority of the kinds of intervention required for development. However they are being given a disproportionate amount of attention There is an issue of cost-effectiveness - about where we choose to spend evaluation budgets and with what coverage There is a risk that by demanding ‘rigorous impact evaluation’, organisations feel compelled to use methodologies like RCT. This may suit output-driven programmes like distributing bed-nets, but, as stated above is inappropriate for interventions such as governance, capacity building, budget support, policy influencing.” Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 24 Handout 14: Guidelines on Understanding and Reporting Changes (by Nigel Simister) Almost all planning, monitoring and evaluation (PME) systems require some element of formal reporting. Regular reports need to be written both for external stakeholders, such as donors, and for internal learning. One of the most essential elements of many reports is the description of changes that are occurring within a project or programme. However, many organisations are weak in this area. Too often, reports that are intended to deal with changes are inadequate. Specifically: reports focus entirely on outputs or activities, not changes; they focus only on positive changes, not on negative changes or areas where expected change has not happened; they report change in an anecdotal way, with insufficient evidence to back the changes up; or reports claim that an organisation is responsible for changes that are more due to external influences. Sometimes this can be due to inadequate PME systems which fail to identify change. However, often it is simply an issue of how change is reported. When working in a project or programme it can be difficult to assess how much information to provide. Too much, and the reporting of the change is buried under pages and pages of reports. Too little, and it is hard for someone without an in-depth knowledge of the project or programme to understand the importance or relevance of the change. When producing brief reports for an external audience (i.e. for people who are not working within your project or programme, and perhaps not even within your own region), you should be looking to provide enough information about individual changes for other people to make a considered opinion about the changes resulting from your work, and about any lessons learned. The list below provides some of the areas that should be considered when reporting on a change or changes. Has there been change? The basic question to address is whether or not things have changed. The changes could be positive or could be negative. In some cases it may also be worth specifically noting changes that have not happened but which should have been expected. How significant was the change? Some changes are relatively minor, whilst others are major and life-changing. It is worth considering whether you need to emphasise the significance of the change within your report. How many organisations/people were affected by the change? Sometimes changes are reported across a number of people or organisations. At other times, you might be reporting a case study based on just one or two people/organisations. In either circumstance, it is useful to know roughly how many people/organisations you think might have been (or will be in the future) affected by the change. Which target groups were affected by the change? Change does not normally happen equally across all types of stakeholders. Some may benefit more than others. A report should be clear about which particular target groups were involved in the change. What was the impact on sub-categories or groups? A report should emphasise any differences between different target groups, if known. For example, some Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 25 changes might affect only specific communities. Simply reporting on change across a large number of different groups might hide significant differences. Was the change intended or not? This can be an extremely valuable source of learning. Sometimes the most profound changes are those that were unplanned. Describing changes of this kind can provide valuable lessons to feed back into planning cycles. Is it likely to be sustainable? Some changes might be long-lasting, whilst others might be relatively short-lived. In some circumstances it might be useful to provide an estimate of how sustainable any reported change is likely to be and to indicate any risks or assumptions that might influence the sustainability. What made the change happen? Reporting on change by itself is interesting but rarely useful for learning purposes. However, if there is an assessment of how the change came about, or what were the key processes leading to it, others may be able to replicate the work (or avoid mistakes in the case of negative changes). Reporting on the key processes that led to a change will also help to substantiate any claim that the change was a result of a particular project or programme’s work. How might the change result in further changes in policies/organisations/people’s lives? Sometimes the implication of change is unclear to outsiders. If you report on an impact – a significant or sustainable change – in people’s lives then it is usually clear what the benefits are. However, if you are reporting on outcomes – the immediate changes resulting from your work – the significance of change may not be clear to everyone. For example, you might report that a government department has higher capacity; a new policy on adaptation has been developed; or there has been increased collaboration between different stakeholders. Within your project/programme the implications may be clear. But for an outsider you might need to spell out why you consider this an important change, and what you hope the ultimate long-term result (or impact) will be. This is basically the “so what?” question. How do changes compare to the baseline (if any)? If you report that 75% of people in a location now have access to clean water, this could be considered as an extremely important change. On the other hand, the situation might be worse than last year! Wherever possible, a report describing change should detail the original situation so that people can understand how large or important the changes are. This applies to both quantitative and qualitative changes. How do changes compare to what was hoped for, or considered realistic? Equally, if you report that 15 national policies were influenced by your efforts the implication is that this is a positive change. However, if you planned to influence 30 policy initiatives, this casts a different light on the information. It is therefore often useful to describe what was originally planned for, so that people reading your report can see immediately the scale of any change relative to your expectations. What evidence do you have for your change? This is arguable the most important aspect to report when describing any change or changes. There is a world of difference between describing the findings of a professionally-conducted, large-scale research study, and reporting findings based on a conversation with a couple of people. The description of evidence does not have to be substantial. It is enough to make an introductory statement such as “the findings of focus-group studies with government officials suggested that …” or “anecdotal evidence suggests that …” or “independent research by government bodies has found that …” This will allow the reader to make up his/her own mind about the value of your evidence. N.B. There is no reason at all why anecdotal evidence of change should not be described in a report. Provided it is clear that the change reported is not based on rigorous data collection and analysis methodologies, impressions of change Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 26 can still be useful. The danger comes when anecdotal evidence is reported as if it were a firm conclusion based on rigorous evidence, instead of tentative conclusions which needs to be further investigated if it is to be properly validated.) How was any change attributable to the work of your organisation? Unless reporting on the external socio-economic environment, you will probably have reason to believe that at least some of the reported changes are attributable to your organisational efforts, or the work of your partners. It is therefore useful to describe how you think your project or programme contributed to any change. Where necessary, you can also describe other factors or organisations that may have contributed. With what degree of confidence can you state the change? PME systems often encourage people to be very definite in their opinions. For example, a logical framework encourages people to say whether a change has happened or not. In many cases, however, you may have some evidence that a change has occurred, but you may not be sure, or you might be sure the change has occurred, but not sure how far your organisation has contributed towards it. In these cases, it is usually better to state the change anyway, and to add some qualifying statements that make it clear how confident you are that change has occurred. If you think there are other possible explanations for why change has happened, it is often useful to state this as well. Again, anyone reading your report can make up his/her own mind provided they have the necessary information on which to base an opinion. Of course it will not always be necessary to report on each of these areas for every single change. Otherwise your reports will be hundreds of pages long, and nobody will ever read them! However, you should seek to ensure that you at least provide enough information so that people can make up their own minds about the value or importance of the changes you describe, or provide references to source material so that people can investigate further if they so choose. Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 27 Handout 15: How to build Impact Monitoring into Existing Systems and Processes The purpose of this exercise is for you to consider to what extent your current planning, monitoring and evaluation systems and processes factor in assessment of change; and how they would need to be developed in order to do so effectively. 1. Based on the series of questions below, please identify: What elements are already in place in your organisation (and in what form – guidance? Specific mention in forms? Policy docs??) Prioritise what you need in order to be able to monitor impact effectively in your projects/programmes 2. Consider how you might be able to meet these needs in the near future Planning Do you clearly articulate the changes (at outcome and impact levels) that you aim to achieve in your projects/programmes? Do you design your M&E and impact assessment strategies in the planning stages of your project/programme? Which stakeholders, if any, do you include these processes (e.g. other members of staff, partners, community representative, others?) Developing Baselines: Do you currently conduct any baselines? If so, do they include a focus on medium and long term changes that the programme expects to achieve? If so, do you identify areas of enquiry and methods for gathering information relevant for monitoring impact? Do you compile and analyse this information? Monitoring: Do your monitoring processes systematically explore changes relating to the project/ programme? If so, do you analyse this information and make choices about future direction based on this analysis? Which stakeholders, if any, do you include these processes (e.g. other members of staff, partners, community representative, others?) Reporting: How do you use monitoring data in your reports? Do you clearly evidence and analyse changes that have been noted? Do you include aspects of learning in these reports? Are you able to effectively communicate the decisions that you are taking as a result? Capacity, Time and Resources: Do staff members have the required skills to design and implement these impact monitoring processes? Are resources and/or time a constraint? Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 28 Handout 16: Checklist to ensure Organisational Learning from Evaluations and Impact Assessments Developing Organisational Memory The organisation has mechanisms for remembering the experience of its current and previous work through the development of highly accessible databases and resource information centres All written reports and key documents are cross referenced and made easily accessible to all staff The organisation is not vulnerable to losing information when staff leave The organisation has a systematic database of all its project and programme work which enables staff and outsiders to identify where expertise can be found within the organisation The information function is given prominence and is resources adequately to enable the organisation to keep its records up to date Applying the Learning The organisation systematically uses its learning to improve its own practice and influence the policy and practice of other organisations or agencies The organisation writes up and publishes its experience for a wider readership without using unnecessary technical jargon The organisation has a strategy for scaling up its impact which reflects the learning it has developed on “what works” The organisation changes its practice and priorities to reflect now knowledge and insights, in an effort to constantly improve its effectiveness The organisation is constantly building its capacity and innovating based on what it has learned Question: How does your organisation measure up? Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 29 Handout 17: Guidance on writing a TOR for Contracting a Consultant to carry Out an Impact Assessment (NB There may be law in your country and/or organisational regulations and procedures governing these matters.) Pre-amble This should mention the commissioning agent(s) and summarise the important about the impact assessment in one paragraph. Context: This should contain an introduction to the programme Theory of Change in relation to it. If there is no theory of change, the context should include the elements contained in it: problems the programme seeks to address, underlying causes of those problems, programme vision and principles of engagement, who it works with, and how to achieve which medium and long term change; and the overall goal of the programme If there is a logical framework, this should also be included here. Purpose There should be a statement about the purpose of the impact assessment and the proposed audiences and uses. Scope, main focuses, and scale of the impact assessment This section addresses – in varying amounts of detail and depth - what the assignment will assess. This will include the Dimension of Change, and possibly the Areas of Enquiry and key assessment questions. However it is important to emphasise that these will be finalized through dialogue with the impact assessment team in the inception phase. Information sources and methodologies This section should develop a provisional list of known data sources for the impact assessment and propose some key methodologies for gathering relevant information. Again, it is important to leave the door open for the assessment team to propose other tools and methods. References to any relevant baseline for impact data should be included here. There should be a statement about expected stakeholder participation. Impact Assessment Process and deliverables, and their timings This section includes the proposed phases of the impact assessment – principally inception, data gathering, analysis, report writing and presentation - the nature of the deliverables. Accurate timings of the phases and the deliverables should be stated. Supervision and responsibilities Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 30 This section includes the management arrangements for the assessment and the respective responsibilities of the commissioners and the assessment team. Required skills, experience, capacity This section sets out expectations of the size and nature of the impact assessment team, and the respective skills and experience of the members. It can set out the parameters of sub-contracting on the part of the assessment team. Budget range An indicative budget is an important piece of information for applicants. This section can also indicate what costs will be met and payment arrangements and timings. How to apply This section should specify what is required of applicants in their submissions. Dates and other arrangements should be included. Information about short-listing and selection is also important. Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 31 Handout 18: Example of a work plan structure An impact assessment work plan will usually contain the following sections. 1. Overview of the interventions including the logic model or Theory Of Change 2. Purpose, audience and uses of the evaluation 3. The assessment framework The high-level focuses of the assessment (the Dimensions of Change). The more detailed areas of enquiry to support investigation against Dimensions of Change The data sources and the methods of collection - including baseline information. 4. Information Collection and Analysis Types of instrument, including for example the key interview guides Approaches to sampling Lists of key informants; and target groups for quantitative surveys 5. Roles and responsibilities A detailed matrix 6. Assumptions, risks and challenges for the assessment Strategies for risks and challenges 7. Work scheduling Refer to dependencies. 8. Deliverables Structure of the report(s) and other deliverables Process for quality assurance. Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 32 Handout 19: Further Reading and Web Sites for Impact Assessment Annie E. Case Foundation, A Handbook of Data Collection Tools for Advocacy and Policy ACT Organisational Capacity Assessment Tool, February 2008 ACT: A guide to assessing our contribution to change O’Flynn, Maureen: Impact Assessment: Understanding and Assessing our Contributions to Change, INTRAC 2010 O’Flynn, Maureen: Tracking Progress in Advocacy: Why and How to Monitor and Evaluate Advocacy Projects and Programmes , INTRAC 2009 Simister Nigel: Monitoring and Evaluation of Capacity Building –Is it Really that Difficult? INTRAC 2010 Bamberger, Michael. Conducting quality impact evaluations under budget, time and data constraints. World Bank, Washington DC, 2006. CAFOD et al. monitoring government policies: A toolkit for civil society organisations in Africa. London (2006?) http://cdg.lathyrus.co.uk/docs/MonitorGovPol.pdf Chambers, Robert et al. Designing impact evaluations: different perspectives. International Initiative for Impact Evaluation, Delhi, 2009. Chapman, Jennifer and Mancini, Antonella. Impact assessment, drivers, dilemmas and deliberations. Sight savers International, Hayward’s Heath, 2008. Chapman, Jennifer and Wameyo, Amboka. Monitoring and evaluating advocacy: a scoping study. ActionAid, London, 2001. Davies, Rick and Dart, Jess. The ‘Most Significant Change’ (MSC) Technique: A Guide to Its Use", 2005. http://www.mande.co.uk/docs/MSCGuide.htm DFID. Monitoring and evaluating information and communication for development programmes. London, 2005. European Evaluation Society: The importance of a methodologically diverse approach to impact evaluation. EES. 2007. European Union. Evaluating socio-economic development. Sourcebook 2. Methods and approaches; participatory approaches and methods. Brussels. 2003. Garbarino, Sabine and Holland, Jeremy. Quantitative and qualitative methods in impact evaluation and measuring results. Governance and Social Development Resource Centre. Birmingham 2009. Grant, Jonathan et al. Capturing Research Impacts. A review of international practice. Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, 2010. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/documented_briefings/2010/RAND_DB57 8.pdf. Jones, Harry. A GUIDE to monitoring and evaluating POLICY INFLUENCE. ODI, London, 2011. Jones, Harry and Hearn, Simon. Outcome Mapping: A realistic alternative for planning, monitoring and evaluation, ODI, London, 2009. http://www.odi.org.uk/resources/details.asp?id=4118&title=outcome-mapping-realisticplanning-monitoring-evaluation Jones, Nicola et al. Improving impact evaluation production and use. ODI. London 2009. Impact assessment 10/11th September 2013 Handouts Page 33