Chapter 9 Guide

advertisement

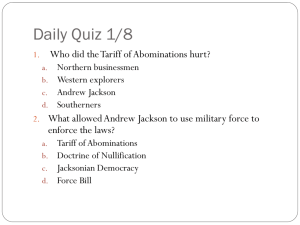

APUSH Chapter 9 Jacksonian America How the United States gained national pride, how the west took shape, and why people were “feeling good” about politics. Summary At first glance Andrew Jackson seems a study in contradictions: an advocate of states' rights who forced South Carolina to back down in the nullification controversy; a champion of the West who vetoed legislation that would have opened easy access to part of the area and who issued the specie circular which brought the region's "flush times" to a disastrous halt; a nationalist who allowed Georgia to ignore the Supreme Court; and a defender of majority rule who vetoed the Bank after the majority's representatives the Congress had passed it. Perhaps he was as his enemies argued simply out for himself. But in the end few would argue that Andrew Jackson was not a popular president if not so much for what he did as for what he was. Jackson symbolized what Americans perceived (or wished) themselves to be - defiant bold independent. He was someone with whom they could identify. So what if the image was a bit contrived it was still a meaningful image. Thus Jackson was reelected by an overwhelming majority and was able to transfer that loyalty to his successor a man who hardly lived up to the image. But all this left a curious question unanswered. Was this new democracy voting for leaders whose programs they favored or rather for images that could be altered and manipulated almost at will? The answer was essential for the future of American politics and the election of 1840 gave the nation a clue. Chapter Themes A. B. C. D. E. American Pride begins to take shape The American West begins to take shape Political Unity Sectionalism Andrew Jackson—a new kind of leader Chapter Objectives—Analysis you must master 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Andrew Jackson's philosophy of government and his impact on the office of the presidency. The nullification theory of John C. Calhoun and President Jackson's reaction to the attempt to put nullification into action. The supplanting of John C. Calhoun by Martin Van Buren as successor to Jackson and the significance of the change. The reasons for the Jacksonian war on the Bank of the United States and the effects of Jackson's veto on the powers of the president and on the American financial system. The causes of the Panic of 1837 and the effect of the panic on the presidency of Van Buren. The differences in party philosophy between the Democrats and the Whigs the reasons for the Whig victory in 1840 and the effect of the election on political campaigning. The negotiations that led to the Webster-Ashburton Treaty and the importance of the treaty in Anglo-American relations. The reasons why John C. Calhoun Henry Clay and Daniel Webster were never able to reach their goal - the White House. Terms—people, places, events, and ideas you should know Alex de Tocqueville Suffrage (dictionary) The Dorr Rebellion Democratic Reforms The Second Party System Jacksonian Democrat The Spoils System Party Convention Calhoun’s Theory of Nullification Martin Van Buren Webster-Hayne Debate States’ Rights vs. National Power Nullification Crisis Missouri Compromise (Chap 8) Compromise of 1833 Black Hawk War Indian Removal Act Worcester vs. Georgia Trail of Tears Seminole War Nicholas Biddle Hard and Soft Money Roger B. Taney Masons Anti-Masons Clay’s American System Election of 1836 Distribution Act Panic of 1837 Independent Treasury Log Cabin Campaign William Henry Harrison John Tyler Caroline Affair Aroostook War WebsterAshburn Treaty Treaty of Wang Hya Penny Press Charles River Bridge vs. Warren Bridge Whig Party A BRIEF HISTORY OF AMERICAN "MAJOR PARTIES" by RICHARD E. BERG-ANDERSSON TheGreenPapers.com Staff Most historical literature refers to the "Party" of the Washington Administration as the Federalists with those in opposition to the policies of that Administration as Antifederalists; however, the use of these designations is, in fact, more than a little inaccurate. The term "Antifederalist" (originally applied to those who had opposed the ratification of the Constitution drafted by the Framers meeting in Convention in Philadelphia in 1787) ceased to have any real meaning as a designation of a political faction once the Constitution formally took effect on 4 March 1789, as anyone serving in the new Federal Government had to take an oath to the new Constitution before entering upon their duties: referring to members of Congress as "Antifederalist", thus, makes little- if any- sense. In addition, there were no real national Political Parties prior to the Presidential Election of 1796 (although loose coalitions between, where not pre-arranged alliances among, State-based "factions"- along the lines of those cosmopolitan vs. localist divisions in Revolutionary Era politics suggested by the historian Jackson Turner Main- would prove to be the basis of the two Parties which would emerge in 1796 and did also have some effect on the political make-up of the first four Congresses). It is best, therefore, to treat those who served in the first four Congresses [1789-1797] as being either Administration (that is, generally allied with those around Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton and Vice President John Adams) or Opposition (those generally associated with Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Congressman James Madison)- with the caveat that, while there is an apparent lineal connection between these groupings and the later Federalists and Republicans, respectively, the Presidency of George Washington was an era of "factions" rather than one of "Parties" and that there were shifting sands in the political landscape of this early era in American political history. For his part, President Washington should be held to be a member of neither faction/future Party; although his political leanings would almost certainly be classified as generally more "Federalist" than "Republican", one has to think he would have been quite surprised to see himself listed in modern American History books as a dyed-in-the-wool Federalist simply because his Vice President would be as President. By the start of the 5th Congress (which coincided with the Inauguration of John Adams as President on 4 March 1797), two national Major Political Parties had emerged from among the strong supporters of the policies of outgoing President Washington and those who had pretty much been opposed to these policies, respectively. Those who had supported the policies of the Washington Administration became known as Federalists because they supported a strong national government as a counterweight to the States; those who had been in Opposition became known as Republicans because they felt that defending the sovereignty of the States against encroachments by the Federal Government was a truer essence of the federal republic known as the United States of America; however, the Federalists, feeling that their contrary vision of what a federal republic should be was the more "republican" in spirit, derisively referred to the Republicans as "democrats" (a term which, at the time, had connotations of the mob rule associated with the then-still very recent Reign of Terror following the French Revolution of 1789). It is true that some Republicans of this era came to see identification with Democracy as a badge of honor and one often sees the term Democratic-Republicans applied to this Party in historical literature (this usage also creating a lineal relationship between these early Republicans and the Democrats of today); however, many political observers, instead, refer to the Republicans of this era as the "old", or "Jeffersonian", Republicans as a better, and more accurate, method of distinguishing them from the Republicans of today. John Quincy Adams was elected as a Republican (in fact, all the candidates for President in 1824 were ostensibly Republicans) but, during the course of the 19th Congress [1825-1827] and on into the 20th Congress [1827-1829], the Republicans in both houses of Congress began to separate themselves into "pro-Adams/anti-Jackson" and "pro-Jackson/anti-Adams" factions- this last feeling strongly that, because of the controversial result of the 1824 Presidential Election, President Adams was not a "legitimate" holder of his office and, thus, coming to favor Senator Andrew Jackson of Tennessee, who had been defeated by Adams for the Presidency in 1824, as the next President of the United States in the upcoming 1828 Presidential Election. It is the practice of TheGreenPapers.com to refer to the first Republican faction, simply, as Adams Republicans, while referring to the second as Jackson Republicans, though political observers have used the term Jackson Democrats for this second Republican faction of the era instead. By the start of the 21st Congress (coinciding with the Inauguration of President Andrew Jackson on 4 March 1829), the two opposing factions within the "old" Republican Party which had become evident in the course of the two preceding Congresses had coalesced into two new Major Parties: the Democratic Republicans (the one-time Jackson Republicans) and the National Republicans (the one-time Adams Republicans). The Democratic Republicans took their name from their identification with the democracy they urged on behalf of the "common man" as well as a strong historical tie they now felt with the old "Jeffersonian" Republicans who- as noted above- had been referred to as "democrats" as a term of derision (the "Jackson" faction thus painting those who supported outgoing President John Quincy Adams as being the contemporary equivalent of the Federalists of Adams' father, President John Adams). The National Republicans, meanwhile, adapted their name from the nationalizing policies pushed by the outgoing Administration of their champion, President Adams. Note that neither faction becoming Party, however, was yet willing to completely give up their identification with the "old" Republicans of the era before the 1824 Presidential Election which had created each faction cum Party in the first place. By the start of the 23rd Congress (which coincided with the Second Inauguration of President Andrew Jackson on 4 March 1833), the one-time Democratic Republicans were becoming more generally known as Democrats, the name itself derived from the aforementioned one-time term of derision hurled by the Federalists at the "old" (or "Jeffersonian") Republicans- with whom those who strongly supported the policies of President Jackson closely identified historically- back in 1796 and 1800. This Major Party has, of course, stayed with the name Democrats ever since. Meanwhile, by the start of the 24th Congress (4 March 1835), the one-time National Republicans were more generally known as Whigs, a name evocative of the political faction in opposition to the English Crown during the era of the Stuarts (17th Century); in addition, the Patriots of the American Revolution were often referred to- by friend and foe alike- as "Whigs" (in contradistinction to the loyalist "Tories"). These 19th Century American Whigs saw themselves as being a bulwark against the "excesses" of the Administration of "King Andrew" Jackson and his heir apparent, Vice President Martin Van Buren, hence the use of this name by this Major Party. The Slavery issue, however, marked the death knell of the Whigs as a Major Party: the Compromise of 1850 (which first adapted the concept of "squatter sovereignty" to the problem of the extension of Slavery to the territories) was lost in the battle over the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 (which first extended this principle north of the northernmost limit of Slavery under the Missouri Compromise of 1820). In the wake of the resultant political fallout, Free Soilers and so-called "Conscience" Whigs joined forces with so-called "Free" Democrats and even denizens of the nativist American (known colloquially as the "Know-Nothing") Party to sow the seeds of a new Major Party: one soon enough to become more generally known as the Republicans, the name of this Major Party to this day. Meanwhile, other Whigs (primarily in the South) joined the Democrats, while a core of so-called "old" Whigs (principally in the Border South) vainly attempted to hold what was, by now, an "anti-Free Soil yet pro-Union" faction together as the winds of Secession and Civil War began to intensify and the end of the 1850s drew nigh (this last remnant of the Whigs would become the core of a short-lived Constitutional Union Party by the 1860 Presidential Election). The 34th Congress [1855-1857], thus, can be seen as a more or less transitional period in which the final decay and decline of the Whigs was becoming offset by the shifting sands of the contemporary antebellum political landscape swiftly producing a new "Democrats versus Republicans" Major Party alignment: one that, at least insofar as the Parties' names are concerned, continues to this very day. What were the defining principals/characteristics of the Political Parties of the Jacksonian era? Political Party Democrats Whigs Republicans Principles and Characteristics Cherokee Trail of Tears Between 1790 and 1830 the population of Georgia increased six-fold. The western push of the settlers created a problem. Georgians continued to take American Indian lands and force both the Cherokee Indians and the Creek Indians into the frontier. By 1825 the Lower Creek had been completely removed from the state under provisions of the Treaty of Indian Springs. By 1827 the Creek were gone. Cherokee had long called western Georgia home. The Cherokee Nation continued in their enchanted land until 1829. It was then that the Georgia Gold Rush became common knowledge. The gold for which Hernando deSoto had relentlessly searched, was discovered in the North Georgia mountains. The Cherokees in 1828 were not nomadic savages. In fact, they had assimilated many European-style customs, including the wearing of gowns by Cherokee women. They built roads, schools and churches, had a system of representational government and were farmers and cattle ranchers. A Cherokee alphabet, the "Talking Leaves" was created by Sequoyah. In 1830 the Congress of the United States passed the "Indian Removal Act." Although many Americans were against the act, most notably Tennessee Congressman Davy Crockett, it passed anyway. President Andrew Jackson quickly signed the bill into law. The Cherokees attempted to fight removal legally by challenging the removal laws in the Supreme Court and by establishing an independent Cherokee Nation. At first the court seemed to rule against the Indians. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, the Court refused to hear a case extending Georgia's laws on the Cherokee because they did not represent a sovereign nation. "I would sooner be honestly damned than hypocritically immortalized" Davy Crockett His political career destroyed because he supported the Cherokee, he left Washington D. C. and headed west to Texas. In 1832, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Cherokee on the same issue in Worcester v. Georgia. In this case Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that the Cherokee Nation was sovereign, making the removal laws invalid. The Cherokee would have to agree to removal in a treaty. The treaty then would have to be ratified by the Senate. By 1835 the Cherokee were divided and despondent. Most supported Principal Chief John Ross, who fought the encroachment of whites starting with the 1832 land lottery. However, a minority(less than 500 out of 17,000 Cherokee in North Georgia) followed Major Ridge, his son John, and Elias Boudinot, who advocated removal. The Treaty of New Echota, signed by Ridge and members of the Treaty Party in 1835, gave Jackson the legal document he needed to remove the Cherokee. Ratification of the treaty by the United States Senate sealed the fate of the Cherokee. Among the few who spoke out against the ratification were Daniel Webster and Henry Clay, but it passed by a single vote. In 1838 the United States began the removal to Oklahoma, fulfilling a promise the government made to Georgia in 1802. Ordered to move on the Cherokee, General John Wool resigned his command in protest, delaying the action. His replacement, General Winfield Scott, arrived at New Echota on May_17, 1838 with 7000 men. Early that summer General Scott and the United States Army began the invasion of the Cherokee Nation. In one of the saddest episodes of our brief history, men, women, and children were taken from their land, herded into makeshift forts with minimal facilities and food, then forced to march a thousand miles(Some made part of the trip by boat in equally horrible conditions). Under the generally indifferent army commanders, human losses for the first groups of Cherokee removed Painting by Robert Lindneux Woolaroc Museum Cried" ("Nunna daul Tsuny"). were extremely high. John Ross made an urgent appeal to Scott, requesting that the general let his people lead the tribe west. General Scott agreed. Ross organized the Cherokee into smaller groups and let them move separately through the wilderness so they could forage for food. Although the parties under Ross left in early fall and arrived in Oklahoma during the brutal winter of 1838-39, he significantly reduced the loss of life among his people. About 4000 Cherokee died as a result of the removal. The route they traversed and the journey itself became known as "The Trail of Tears" or, as a direct translation from Cherokee, "The Trail Where They Ironically, just as the Creeks killed Chief McIntosh for signing the Treaty of Indian Springs, the Cherokee killed Major Ridge, his son and Elias Boudinot for signing the Treaty of New Echota. Chief John Ross, who valiantly resisted the forced removal of the Cherokee, lost his wife Quatie during the western movement of the Cherokee. And so a country formed fifty years earlier on the premise "...that all men are created equal, and that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, among these the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.." brutally closed the curtain on a culture that had done no wrong. Question: How did white Americans' attitudes toward Native Americans evolve during the early nineteenth century? What factors led to the decision to remove the Indians from land east of the Mississippi? What other alternatives were available and why were they rejected? How did the Indians respond to the government's policy toward them? (Be sure to consult previous chapters when answering this question.) Firsthand Account of the Removal of the Cherokees By; Private John G. Burnett: Birthday Story of Private John G. Burnett, Captain Abraham McClellan’s Company, 2nd Regiment, 2nd Brigade, Mounted Infantry, Cherokee Indian Removal, 1838-39. Children:This is my birthday, December 11, 1890, I am eighty years old today. I was born at Kings Iron Works in Sulllivan County, Tennessee, December the 11th, 1810. I grew into manhood fishing in Beaver Creek and roaming through the forest hunting the deer and the wild boar and the timber wolf. Often spending weeks at a time in the solitary wilderness with no companions but my rifle, hunting knife, and a small hatchet that I carried in my belt in all of my wilderness wanderings. On these long hunting trips I met and became acquainted with many of the Cherokee Indians, hunting with them by day and sleeping around their camp fires by night. I learned to speak their language, and they taught me the arts of trailing and building traps and snares. On one of my long hunts in the fall of 1829, I found a young Cherokee who had been shot by a roving band of hunters and who had eluded his pursuers and concealed himself under a shelving rock. Weak from loss of blood, the poor creature was unable to walk and almost famished for water. I carried him to a spring, bathed and bandaged the bullet wound, and built a shelter out of bark peeled from a dead chestnut tree. I nursed and protected him feeding him on chestnuts and toasted deer meat. When he was able to travel I accompanied him to the home of his people and remained so long that I was given up for lost. By this time I had become an expert rifleman and fairly good archer and a good trapper and spent most of my time in the forest in quest of game. The removal of Cherokee Indians from their life long homes in the year of 1838 found me a young man in the prime of life and a Private soldier in the American Army. Being acquainted with many of the Indians and able to fluently speak their language, I was sent as interpreter into the Smoky Mountain Country in May, 1838, and witnessed the execution of the most brutal order in the History of American Warfare. I saw the helpless Cherokees arrested and dragged from their homes, and driven at the bayonet point into the stockades. And in the chill of a drizzling rain on an October morning I saw them loaded like cattle or sheep into six hundred and forty-five wagons and started toward the west. One can never forget the sadness and solemnity of that morning. Chief John Ross led in prayer and when the bugle sounded and the wagons started rolling many of the children rose to their feet and waved their little hands good-by to their mountain homes, knowing they were leaving them forever. Many of these helpless people did not have blankets and many of them had been driven from home barefooted. On the morning of November the 17th we encountered a terrific sleet and snow storm with freezing temperatures and from that day until we reached the end of the fateful journey on March the 26th, 1839, the sufferings of the Cherokees were awful. The trail of the exiles was a trail of death. They had to sleep in the wagons and on the ground without fire. And I have known as many as twenty-two of them to die in one night of pneumonia due to ill treatment, cold, and exposure. Among this number was the beautiful Christian wife of Chief John Ross. This noble hearted woman died a martyr to childhood, giving her only blanket for the protection of a sick child. She rode thinly clad through a blinding sleet and snow storm, developed pneumonia and died in the still hours of a bleak winter night, with her head resting on Lieutenant Greggs saddle blanket. I made the long journey to the west with the Cherokees and did all that a Private soldier could do to alleviate their sufferings. When on guard duty at night I have many times walked my beat in my blouse in order that some sick child might have the warmth of my overcoat. I was on guard duty the night Mrs. Ross died. When relieved at midnight I did not retire, but remained around the wagon out of sympathy for Chief Ross, and at daylight was detailed by Captain McClellan to assist in the burial like the other unfortunates who died on the way. Her unconfined body was buried in a shallow grave by the roadside far from her native home, and the sorrowing Cavalcade moved on. Being a young man, I mingled freely with the young women and girls. I have spent many pleasant hours with them when I was supposed to be under my blanket, and they have many times sung their mountain songs for me, this being all that they could do to repay my kindness. And with all my association with Indian girls from October 1829 to March 26th 1839, I did not meet one who was a moral prostitute. They are kind and tender hearted and many of them are beautiful. The only trouble that I had with anybody on the entire journey to the west was a brutal teamster by the name of Ben McDonal, who was using his whip on an old feeble Cherokee to hasten him into the wagon. The sight of that old and nearly blind creature quivering under the lashes of a bull whip was too much for me. I attempted to stop McDonal and it ended in a personal encounter. He lashed me across the face, the wire tip on his whip cutting a bad gash in my cheek. The little hatchet that I had carried in my hunting days was in my belt and McDonal was carried unconscious from the scene. I was placed under guard but Ensign Henry Bullock and Private Elkanah Millard had both witnessed the encounter. They gave Captain McClellan the facts and I was never brought to trial. Years later I met 2nd Lieutenant Riley and Ensign Bullock at Bristol at John Roberson’s show, and Bullock jokingly reminded me that there was a case still pending against me before a court martial and wanted to know how much longer I was going to have the trial put off? The long painful journey to the west ended March 26th, 1839, with four-thousand silent graves reaching from the foothills of the Smoky Mountains to what is known as Indian territory in the West. And covetousness on the part of the white race was the cause of all that the Cherokees had to suffer. Ever since Ferdinand DeSoto made his journey through the Indian country in the year 1540, there had been a tradition of a rich gold mine somewhere in the Smoky Mountain Country, and I think the tradition was true. At a festival at Echota on Christmas night 1829, I danced and played with Indian girls who were wearing ornaments around their neck that looked like gold. In the year 1828, a little Indian boy living on Ward creek had sold a gold nugget to a white trader, and that nugget sealed the doom of the Cherokees. In a short time the country was overrun with armed brigands claiming to be government agents, who paid no attention to the rights of the Indians who were the legal possessors of the country. Crimes were committed that were a disgrace to civilization. Men were shot in cold blood, lands were confiscated. Homes were burned and the inhabitants driven out by the gold-hungry brigands. Chief Junaluska was personally acquainted with President Andrew Jackson. Junaluska had taken 500 of the flower of his Cherokee scouts and helped Jackson to win the battle of the Horse Shoe, leaving 33 of them dead on the field. And in that battle Junaluska had drove his tomahawk through the skull of a Creek warrior, when the Creek had Jackson at his mercy. Chief John Ross sent Junaluska as an envoy to plead with President Jackson for protection for his people, but Jackson’s manner was cold and indifferent toward the rugged son of the forest who had saved his life. He met Junaluska, heard his plea but curtly said, "Sir, your audience is ended. There is nothing I can do for you." The doom of the Cherokee was sealed. Washington, D.C., had decreed that they must be driven West and their lands given to the white man, and in May 1838, an army of 4000 regulars, and 3000 volunteer soldiers under command of General Winfield Scott, marched into the Indian country and wrote the blackest chapter on the pages of American history. Men working in the fields were arrested and driven to the stockades. Women were dragged from their homes by soldiers whose language they could not understand. Children were often separated from their parents and driven into the stockades with the sky for a blanket and the earth for a pillow. And often the old and infirm were prodded with bayonets to hasten them to the stockades. In one home death had come during the night. A little sad-faced child had died and was lying on a bear skin couch and some women were preparing the little body for burial. All were arrested and driven out leaving the child in the cabin. I don’t know who buried the body. In another home was a frail mother, apparently a widow and three small children, one just a baby. When told that she must go, the mother gathered the children at her feet, prayed a humble prayer in her native tongue, patted the old family dog on the head, told the faithful creature good-by, with a baby strapped on her back and leading a child with each hand started on her exile. But the task was too great for that frail mother. A stroke of heart failure relieved her sufferings. She sunk and died with her baby on her back, and her other two children clinging to her hands. Chief Junaluska who had saved President Jackson’s life at the battle of Horse Shoe witnessed this scene, the tears gushing down his cheeks and lifting his cap he turned his face toward the heavens and said, "Oh my God, if I had known at the battle of the Horse Shoe what I know now, American history would have been differently written." At this time, 1890, we are too near the removal of the Cherokees for our young people to fully understand the enormity of the crime that was committed against a helpless race. Truth is, the facts are being concealed from the young people of today. School children of today do not know that we are living on lands that were taken from a helpless race at the bayonet point to satisfy the white man’s greed. Future generations will read and condemn the act and I do hope posterity will remember that private soldiers like myself, and like the four Cherokees who were forced by General Scott to shoot an Indian Chief and his children, had to execute the orders of our superiors. We had no choice in the matter. Twenty-five years after the removal it was my privilege to meet a large company of the Cherokees in uniform of the Confederate Army under command of Colonel Thomas. They were encamped at Zollicoffer and I went to see them. Most of them were just boys at the time of the removal but they instantly recognized me as "the soldier that was good to us". Being able to talk to them in their native language I had an enjoyable day with them. From them I learned that Chief John Ross was still ruler in the nation in 1863. And I wonder if he is still living? He was a noble-hearted fellow and suffered a lot for his race. At one time, he was arrested and thrown into a dirty jail in an effort to break his spirit, but he remained true to his people and led them in prayer when they started on their exile. And his Christian wife sacrificed her life for a little girl who had pneumonia. The Anglo-Saxon race would build a towering monument to perpetuate her noble act in giving her only blanket for comfort of a sick child. Incidentally the child recovered, but Mrs. Ross is sleeping in a unmarked grave far from her native Smoky Mountain home. When Scott invaded the Indian country some of the Cherokees fled to caves and dens in the mountains and were never captured and they are there today. I have long intended going there and trying to find them but I have put off going from year to year and now I am too feeble to ride that far. The fleeing years have come and gone and old age has overtaken me. I can truthfully say that neither my rifle nor my knife were stained with Cherokee blood. I can truthfully say that I did my best for them when they certainly did need a friend. Twenty-five years after the removal I still lived in their memory as "the soldier that was good to us". However, murder is murder whether committed by the villain skulking in the dark or by uniformed men stepping to the strains of martial music. Murder is murder, and somebody must answer. Somebody must explain the streams of blood that flowed in the Indian country Murder is murder, and somebody must answer. Somebody must explain the streams of blood that flowed in the Indian country in the summer of 1838. Somebody must explain the 4000 silent graves that mark the trail of the Cherokees to their exile. I wish I could forget it all, but the picture of 645 wagons lumbering over the frozen ground with their cargo of suffering humanity still lingers in my memory. Let the historian of a future day tell the sad story with its sighs, its tears and dying groans. Let the great Judge of all the earth weigh our actions and reward us according to our work. Children - Thus ends my promised birthday story. This December the 11th 1890. Jackson’s Message to Congress Concerning his Veto of the Banking Bill Please read the message and consider whether Jackson’s veto was personally motivated or politically motivated . The present corporate body, denominated the president, directors, and company of the Bank of the United States, will have existed at the time this act is intended to take effect twenty years. It enjoys an exclusive privilege of banking under the authority of the General Government, a monopoly of its favor and support, and, as a necessary consequence, almost a monopoly of the foreign and domestic exchange. The powers, privileges, and favors bestowed upon it in the original charter, by increasing the value of the stock far above its par value, operated as a gratuity of many millions to the stockholders.... The act before me proposes another gratuity to the holders of the same stock, and in many cases to the same men, of at least seven millions more....It is not our own citizens only who are to receive the bounty of our Government. More than eight millions of the stock of this bank are held by foreigners. By this act the American Republic proposes virtually to make them a present of some millions of dollars. Every monopoly and all exclusive privileges are granted at the expense of the public, which ought to receive a fair equivalent. The many millions which this act proposes to bestow on the stockholders of the existing bank must come directly or indirectly out of the earnings of the American people.... It appears that more than a fourth part of the stock is held by foreigners and the residue is held by a few hundred of our own citizens, chiefly of the richest class. Is there no danger to our liberty and independence in a bank that in its nature has so little to bind it to our country? The president of the bank has told us that most of the State banks exist by its forbearance. Should its influence become concentered, as it may under the operation of such an act as this, in the hands of a self-elected directory whose interests are identified with those of the foreign stockholders, will there not be cause to tremble for the purity of our elections in peace and for the independence of our country in war? Their power would be great whenever they might choose to exert it; but if this monopoly were regularly renewed every fifteen or twenty years on terms proposed by themselves, they might seldom in peace put forth their strength to influence elections or control the affairs of the nation. But if any private citizen or public functionary should interpose to curtail its powers or prevent a renewal of its privileges, it can not be doubted that he would be made to feel its influence. It is to be regretted that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes. Distinctions in society will always exist under every just government. Equality of talents, of education, or of wealth can not be produced by human institutions. In the full enjoyment of the gifts of Heaven and the fruits of superior industry, economy, and virtue, every man is equally entitled to protection by law; but when the laws undertake to add to these natural and just advantages artificial distinctions, to grant titles, gratuities, and exclusive privileges, to make the rich richer and the potent more powerful, the humble members of society the farmers, mechanics, and laborers who have neither the time nor the means of securing like favors to themselves, have a right to complain of the injustice of their Government. There are no necessary evils in government. Its evils exist only in its abuses. If it would confine itself to equal protection, and, as Heaven does its rains, shower its favors alike on the high and the low, the rich and the poor, it would be an unqualified blessing. In the act before me there seems to be a wide and unnecessary departure from these just principles. Nor is our Government to be maintained or our Union preserved by invasions of the rights and powers of the several States. In thus attempting to make our General Government strong we make it weak. Its true strength consists in leaving individuals and States as much as possible to themselves in making itself felt, not in its power, but in its beneficence; not in its control, but in its protection; not in binding the States more closely to the center, but leaving each to move unobstructed in its proper orbit. Experience should teach us wisdom. Most of the difficulties our Government now encounters and most of the dangers which impend over our Union have sprung from an abandonment of the legitimate objects of Government by our national legislation, and the adoption of such principles as are embodied in this act. Many of our rich men have not been content with equal protection and equal benefits, but have besought us to make them richer by act of Congress. By attempting to gratify their desires we have in the results of our legislation arrayed section against section, interest against interest, and man against man, in a fearful commotion which threatens to shake the foundations of our Union. It is time to pause in our career to review our principles, and if possible revive that devoted patriotism and spirit of compromise which distinguished the sages of the Revolution and the fathers of our Union. If we can not at once, in justice to interests vested under improvident legislation, make our Government what it ought to be, we can at least take a stand against all new grants of monopolies and exclusive privileges, against any prostitution of our Government to the advancement of the few at the expense of the many, and in favor of compromise and gradual reform in our code of laws and system of political economy....