Contemporary Literary and Cultural Theory EN3000 – Fall/Winter

advertisement

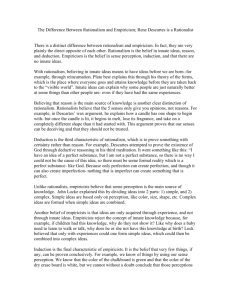

Contemporary Literary and Cultural Theory EN3000 – Fall/Winter 2011/2012 – Nemanja Protic Lecture 3 – Modern Sensibilities I: Rationalism & Empiricism – Sept 22 REVIEW: Mikhail Bakhtin (1895-1975) - Key features of his work are inter-disciplinary and a dedication to man as a concrete historical subject: ‘it is only on a concrete historical subject that a theoretical problem can be solved.’ - Critic of Russian Formalism because of its: o Objective Empiricism – reducing the text to its materiality. o Subjective Empiricism – dissolving the text into the psychic states felt by those who produce or perceive the text. - “The [written] work cannot be understood outside the entity in ‘literature’. But this latter entity, taken as a whole, as well as its elements… cannot be understood outside the entire ‘ideological life’. This entity in turn cannot be studied… outside the unitary socio-economic laws.” – Bakhtin, quoted in Todorov 36). Dialogic (Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms) “Characterized or constituted by the interactive, responsive nature of dialogue rather than by the single-mindedness of monologue. The term is important in the writings of the Russian theorist Mikhail Bakhtin, whose [work]… contrasts the dialogic or polyphonic interplay of various characters’ voices in Dostoevsky’s novels with the ‘monological’ subordination of characters to the single viewpoint of the author in Tolstoy’s. [Bakhtin also argues], against Saussure’s theory of a langue, that actual utterances are ‘dialogic’ in that they are embedded in a context of dialogue and thus respond to an interlocutor’s previous utterances and/or try to draw a particular response from a specific auditor.” The Human Sciences - Natural sciences vs. Human sciences: o Believes that there is a parallelism. o Differences in the object of study (reified object vs. text/discourse). Natural science – concrete material objects – objects don’t talk back to us. Human science – texts and discourses – object of the study talks back to us. o Differences in method (accuracy vs. depth) Natural science – accuracy. Human science – depth. - Discourse (e.g. pop music): o Concepts, ideas and notions that we can use to talk about a topic. o High vs. low art (aesthetics). o Statements of judgement (good, bad, trivial, etc.) o Individual names (the Beatles, Michael Jackson, etc.) [cultural studies, history]. Different forms. o Concepts such as commercialism [economics, social studies], sexuality [biology, cultural studies], taste [aesthetics], population/general public [sociology, geography]. o Discourses are always changing with new ‘pop culture’ people and changes accordingly. Dialogism - Exists on all levels of discourse: o Language and utterance, which always exist as social facts: ‘No utterance… can be attributed to the speaker exclusively; it is the product of the interaction of interlocutors, and… the product of the whole complex social situation in which it has occurred.’ (30) Drags distinction between language and utterance. Utterance is a specific usage of language. The historical baggage that comes with a word is what creates a meaning to the people. It always carries the weight that it was used to in the past. o The psychological individual: ‘Human personality becomes historically real and culturally productive only insofar as it is a part of a social whole, in its class and through its class.’ (31) o Text and art: The artistic ‘is a specific form of the relation between creator and contemplators, fixed in the artistic work.’ (21). Bakhtin’s ‘Philosophical Anthropology’ - ‘Otherness’ as a transgredient of consciousness. - “Our own idea (or perhaps illusion) of what is a whole person, an accomplished being, can only come from the perception of someone else, and not from the perception we have of ourselves.” – Todorov 95 - “It is only in another human being that I find an aesthetically (and ethically) convincing experience of human finitude, of a marked-off empirical objectivity… Only another human being can give me the appearance of being consubstantial with the external world…For only the other can be embraced, totally surrounded, and explored lovingly in all of his or her limits.” – Bakhtin, quoted in Todorov 95 How to Read Bakhtin - What does Bakhtin’s work mean in the context of 1920s Russia? - What does it mean in the context of 1960s Russia, when it is ‘rediscovered’? - What does it mean in 1970s Franch when it first comes to the attention of Western European theorists? - What is the role of cultural translators such as Todorov and Kristeva? - What does Bakhtin’s work mean today, in a culture that is in many ways different from 1970s France, and how does this work’s reception in 1970s France – especially within the context of structuralism – affect our reading of this work? - Bakhtin’s work is, therefore, a palimpsest of cultural reading, a dialogical network of relations that all, ultimately, matter. Palimpsest (Concise Oxford Companion to Classical Literature) “Manuscript in which the text has been written over an effaced earlier text. The practice of writing on the renovated surface of an old manuscript was frequent among the monks of the Middle Ages, and since perfect removal of the original writing was seldom achieved, it has proved possible to recover valuable old texts of e.g. The bible, Cicero and Plautus. Rene Descartes (1596-1650) - Born in La Haye en Touraine (now Descartes) in France on March 31, 1596. - The ‘Father of Modern Philosophy’ o Before the modern period, there was little philosophy. - Key figure in the Scientific Revolution, his influence extends into the realms of mathematics (analytical geometry) while he also wrote on physics and astronomy; human biology and physiology, etc. - When Galileo was condemned by the Catholic Church for his ‘heresies’, Descartes stopped publication on his book ‘La Monde.’ - Spent most of his adult life in Holland, known for its relatively secular sociopolitical system which embraced freedom of thought. - Died of pneumonia in Stockholm, Sweden on February 11, 1650. The Modern Era - Rebellion against traditional forms of authority such as the Church and the Monarchy, and an attempt to establish the autonomy of the individual’s capability to reason. - Rise of democratic political forms, based on the autonomy of the individual. - This democracy is often described as ‘liberal’ – concerned with rights of individuals – and as closely related to capitalist economic forms and commerce epitomised by the Industrial Revolution and the rise of machine production. - Modern thought, furthermore, builds on this faith in reason and human autonomy, and leads to a proliferation of subjectivist and individualistic ways of conceptualising the world. Modern Thought – Changes in Emphasis - Traditional learning (exegesis/interpretation of ancient texts) vs. A creation of new systematic method which did not rely solely on authority of ancient texts. o Rationalism (Descartes). o Empiricism (Locke). - Latin vs. Vernacular (democratization of thought). - Philosophical theologists vs. theological philosophers. o Tradition: religion and philosophy. o Modern: god still has a place in the system but they use rationality and individual methods of things which become primary – religion takes a back seat to philosophy. - Theological humanism vs. natural humanism. - Nature as theocentric vs. nature as mechanistic. o Traditional: god is seen as the primary mover – the study of human sciences, they harmonize it with the study of god. o Modern: the study of nature comes first – god is there as the entity that created the universe – the goal becomes to find the law which run the universe independent from God’s control. The Rise of Modern Science - Begin to give explanations of things in nature which were previously explained by God. - Copernicus – proposes idea that it’s not earth that’s the center of the universe but that the sun is and what we are seeing is an optical allusion. - Newton – explains things with math – why things fall. Descartes’ Mathematical Method - The mathematical method provides answers which cannot be doubted. - Mathematical solutions are eternal. - The mathematical method cannot be challenged – all must assent to its validity. o No one can argue with the system that 1+1 always = 2. Descartes’ Method - Like the medieval thinks who used syllogistic reasoning, Descartes wants to find truths which cannot be refuted – he is seeking things which must necessarily be true – these are the first principles of philosophy; upon which he can build a system of absolute truths. - At the same time, he seeks to move beyond simple syllogism, in order to find new truths. - Philosophy (or metaphysics), as mathematics, must rest on first principles which cannot be conclusions of any deductive argument. Aristotelian Logic (Syllogism) - Aristotle defines syllogism as ‘a discourse in which, certain things having been supposed, something different from the things supposed results of necessity because these things are so’ (Priori analytics). - The syllogism is at the root of deductive reasoning, the goal of which is to show that a conclusion necessarily follows from a set of premises. o For example: Premise 1 – all men are mortal Premise 2 – Socrates is a man Conclusion – Socrates is mortal - Never a source of new knowledge – you can never base a thought on syllogism because you always need to come back to the basic notion. Descartes’ Method - Mathematical first principles agree with what we perceive through our senses, metaphysical (philosophical) first principles do not. - Descartes: ‘The primary notions that are the presuppositions of geometrical proofs harmonize with the use of our senses, and are readily granted by all… On the contrary, nothing in metaphysics causes more trouble than the making the perceptions of its primary notions clear and distinct. For, though in their own nature they are as intelligible as, or even more intelligible than those that geometricians study, yet being contradicted by the many preconceptions of our senses to which we have since our earliest years been accustomed, they cannot be perfectly apprehended except by those who give strenuous attention and study to them, and withdraw their minds as far as possible from matters corporeal”. Innate vs. Acquired Ideas… - Descartes writes, ‘I never wrote or concluded that the mind required innate ideas which were in some way different from its faculty of thinking.’ We are accustomed to say that certain diseases are innate in certain families, not because ‘the babes of these families suffer from these diseases in their mother’s womb, but because they are born with a certain disposition or propensity for contracting them.’ In other words, we have a faculty of thinking, and this faculty, owing to its innate constitution, conceives thinking in certain ways… Statements of this sort tend to suggest that for Descartes innate ideas are a priori forms of thought which are not really distinct from the faculty of thinking… [Certain first principles] are not present in the mind as objects of thought from the beginning; but they are virtually present in the sense that by reason of its innate constitution the mind thinks in these ways. Descartes’ theory would thus constitute to some extent an anticipation of Kant’s theory of the a priori, with the important difference that Descartes does not say, and indeed does not believe, that the a priori forms of thought are applicable only within the field of sense-experience. - “Yet it is clear that Descartes does not restrict innate ideas to forms of thought or moulds of conception. For he speaks of all clear and distinct ideas as innate. The idea of God, for example, is said to be innate. Such ideas are not, indeed, innate in the sense that they are present in the baby’s mind as fully-fledged ideas. But the mind produces them, as it were, out of its own potentialities on the occasion of experience of some sort. It does not derive them from sense-experience.” Analysis (Descartes) - “Analytic demonstrations are designed to guide the mind, so that all prejudices preventing us from grasping a first principle will be removed, and the first principles themselves can be intuited. An analytic demonstration, therefore, is… a process of ‘reasoning up’ to first principles – the upward movement taking place as prejudice is removed.” o Intuited – you need to intuit the truth that exists within your mind. Modal Logic (Modalities) - “The modality of a statement or proposition 5 is the manner in which 5’s truth holds. Statements or propositions can be necessary, possible or contingent. For example, while the statement ‘Aristotle is Plato’s student’ is actually true, it is only - - contingently true. It is possible that Aristotle never met Plato. By contrast, the statement ‘Aristotle is self-identical’ is necessarily true. Aristotle could not have failed to be self-identical… The central issue in the epistemology of modality concerns how we come to have justified beliefs or knowledge of modality.” – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Modality of necessity (1+1=2 or I think, I am) o Modality of necessity – if something is necessarily true, it means that we can build a philosophical modality on top of it. o I think, I am Cannot deny the fact that I’m thinking. Thinking = being for Descartes. The relation thought is the same of the relation that you are thinking about. By thinking I am making it so. Modality of contingency – my shirt is blue. John Locke (1632-1704) - Born in Wrington, Somerset, near Bristol on August 29, 1632. - Attended Christ Church, Oxford, but he found works of modern philosophers such as Descartes more interesting than the classical material taught at the university. - Studied medicine, worked as a physician. - His work is equally important, if not more so, in the realm of social and political thought as in the realm of philosophy: “His writings influenced Voltaire and Rousseau, many Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, as well as the American revolutionaries. His contributions to classical republicanism and liberal theory are reflected in the American Declaration of Independence.” [Wikipedia] - Likes Descartes, he spent time in Holland, escaping political persecution. - Died on October 28, 1704 in England. Empiricism (The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy) “The permanent strand in philosophy that attempts to tie knowledge to experience. Experience is thought of either as the sensory contents of consciousness, or as whatever is expressed in some designated class of statements that can be observed to be true by the use of the senses. Empiricism denies that there is any knowledge outside this class, or at least outside whatever is given by legitimate theorizing on the basis of this class. It may take the form of denying that there is any a priori knowledge, or knowledge of necessary truths, or any innate or intuitive knowledge or general principles gaining credibility simply through the use of reason; it is thus principally contrasted with rationalism. Locke on Rationalism (Book I, Chapter I) “It is an established opinion amongst some men, that there are in the understanding certain innate principles; some primary notions [and]… characters, as it were stamped upon the mind of man; which the soul receives in its very first being, and brings into the world with it. It would be sufficient to convince unprejudiced readers of the falseness of this supposition, if I should only show (as I hope I shall in the following parts of this discourse) how men, barely by the use of their natural faculties, may attain to all the knowledge they have, without the help of any innate impressions; and may arrive at certainty, without any such original notions or principles.” - This theory is too complicated and it can be explained much simpler. Ockham’s razor (A Dictionary of Psychology) “The principle of economy of explanation according to which entitles (usually interpreted as assumptions) should not be multiplied beyond necessity (Entia non sunt multiplicanda praetor necessitate), and hence simple explanations should be preferred to more complex ones. Another version of the principle attributed to Ockham is that ‘what can be explained by the assumptions of fewer things is vainly explained by the assumption of more things.” - Locke believes that math doesn’t tell us anything about the real world. Deductive vs. Inductive Reasoning - Deductive reasoning – proceeds from a set of premises to a conclusion in order to reach necessary truth. A syllogism is an example of deductive reasoning. - Inductive reasoning – proceeds from observable, experienced, individual instances to a general conclusion to reach a probable or contingent truth. o A basketball is round, o A soccer ball is round, o A volleyball is round, o A tennis ball is round, o A gold ball is round, therefore, o All balls are round (get your mind out of the gutter). A Priori (The Oxford Companion to the Mind) “A term applied to statements to reflect the status of our knowledge of their truth (or falsehood). IT means literally ‘from what comes before’, where the answer to ‘before what?’ is understood to be ‘experience’. Loosely, one may speak of knowing some truth ‘a priori’ where it is possible to infer the truth without having to experience the state of affairs in virtue of which it is true, but in strict philosophical usage, an a priori truth must be knowable independently of all experience. Kant held that the criteria of a priori knowledge where (i) necessity, for ‘experience teaches us that a thing is so and so, but no that it cannot be otherwise’ and (ii) universality, for all experience can confer on a judgement is ‘assumed and comparative universality through induction.” Locke on Simple Ideas (Book I, Chapter I) “The senses at first let in particular ideas, and furnish the yet empty cabinet and the mind by degrees growing familiar with some of them, they are lodged in the memory, and names got to them. Afterwards, the mind proceeding further, abstracts them, and by degrees learns the use of general names. In this manner the mind comes to be furnished with ideas and language, the materials about which to exercise its discursive faculty. And the use of reason becomes daily more visible, as these materials that give it employment increase.” Body and Spirit By the complex idea of extended, figured, coloured and all other sensible qualities, which is all that we know of it, we are as far from the idea of the substance of body, as if we knew nothing at all: nor after all the acquaintance and familiarity which we imagine we have with matter, and the many qualities men assure themselves they perceive and know in bodies, will it perhaps upon examination be found, that they have any more or clearer primary ideas belonging to body, and they have belonging to immaterial spirit. The primary ideas we have peculiar to body, as contradistinguished to spirit, are the cohesion of solid, and consequently separable, parts and a power of communicating motion by impulse. These, I think, are the original ideas proper and peculiar to body; for figure is but the consequence of finite extension. The ideas we have belonging and peculiar to spirit, are thinking, and will, or a power of putting body into motion by thought, and, which is consequent to it, liberty. For, as body cannot by communicate its motion by impulse to another body, which it meets with at rest, so the mind can put bodies into motion, or forbear to do so, as it pleases. The ideas of existence, duration and mobility are common to them both.