Dan's Comments - WordPress.com

advertisement

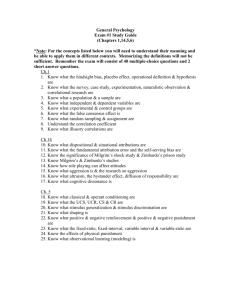

Milner 1 Brittni Milner Mr. Ekstrand WRI 111: “We Our Own Devil” 13 November 2013 Is Neuroscience the Answer? Over time, society has struggled to determine the roots of evil behavior. As technology advances, scientists often think that they have solved the problem; however, new information is always released that leaves the question of what causes evil behavior unanswered again. Some people believe that biology is responsible whereas others think that it depends on the social situation. Because of this, society has struggled to determine whether or not a person is guilty in legal situations. The Lucifer Effect by Philip Zimbardo, Incognito by David Eagleman, and The Brain on the Stand by Jeffrey Rosen all make contrasting arguments in response to the same question – To what extent is the brain responsible for evil behavior? To begin with, evil behavior needs to be defined. Zimbardo claims that “evil consists in intentionally behaving in ways that harm, abuse, demean, dehumanize, or destroy innocent others – or using one’s authority and systematic power to encourage or permit others to do so on your behalf” (5). Throughout The Lucifer Effect, Zimbardo takes an incrementalist-situationalist approach. He believes that everyone is capable of changing towards the good or bad side depending on the circumstances. “In short, we can learn to become good or evil regardless of our genetic inheritance, personality, or family legacy” (Zimbardo 7). Milner 2 The Milgram Study is an important example brought up in Zimbardo’s The Lucifer Effect. The results of the study demonstrate that most of us would be so obedient to shock a person to death if a guy in a lab coat told us to. Additionally, even more of us would sit there witnessing a partner shock someone to death. Outside sources, such as figures of authority and peers, influence the decisions that we make. However, even though this evidence is supported through experiment, most of us see ourselves as an exception to the trend. By using the Milgram Study as an example, Zimbardo is able to convince the audience that social situations and authority play a significant role in the likelihood to take part in evil behavior. Zimbardo does not only argue that our behaviors depend on the situation, but also that our actions are developed by the society in which we live. Zimbardo claims “our personal identities are socially situated. We are where we live, eat, work, and make love. It is possible to predict a wide range of your attitudes and behavior from knowing any combination of ‘status’ factors—your ethnicity, social class, education, and religion and where you live—more accurately than by knowing your personal traits” (319). Therefore, who we are and how we act depends on our social situations. After reading The Lucifer Effect, Zimbardo convinced me to believe that the surrounding environment affects a person’s likelihood to do an evil act. I agree with Zimbardo’s idea that peers often influence the decisions that we make. Typically, I choose to do the same as my friends even if it is against my beliefs. This is an outside source that is affecting my decision of whether or not to take part in an evil act. Even though there are influences that affect our decision-making, I believe that the choice is ultimately ours. Therefore, I think we are responsible for every wrong decision that we Milner 3 make, and we should be punished accordingly. However, this has nothing to do with neuroscience, which others believe is responsible for how we act. In contrast to Zimbardo’s The Lucifer Effect, Eaglman’s Incognito uses biology as a way to determine whether or not people commit evil acts. Therefore, society possesses different perspectives, dissimilar personalities, and varied capacities for decision-making. Eagleman’s argument is convincing because he uses neuroscience evidence to support his claim. “A slight change in the balance of brain chemistry can cause large changes in the behavior” (Eagleman 157). He also uses statistics, which confirms his idea that our genes are responsible for who we are and the decisions that we make. Eagleman claims, “If you are a carrier of a particular set of genes, your probability of committing a violent crime goes up by eight hundred and eighty-two percent” (158). This demonstrates that there is an obvious correlation between our genes and our behaviors. Furthermore, Eagleman questions whether or not we have freewill because we cannot choose our behaviors or actions since we cannot choose our biology. Eagleman makes the claim that everyone has different ‘starting’ points because everyone’s brain is unique. Therefore, everyone has a different developmental path, which cannot be chosen. “Who we are runs well below the surface below the surface of our conscious access, and the details reach back in time before our birth, when the meeting of a sperm and egg granted us with certain attributes and not others” (Eagleman 159). My thinking changed after reading Incognito by Eagleman. I was left feeling that not everyone is free to make appropriate choices in society. As a result, I think that people should not be blamed for their decisions since it is the fault of biology. However, I started questioning how our legal system deals with this question. Are the alcoholic, drug Milner 4 addict, and other kinds of compulsives acting involuntary? Eagleman convinced me to believe that maybe brain scans should be used in court because they would provide us with the opportunity to tell what someone thought based on his or her behavior. By using technology, we have the chance to determine if someone’s actions were intentional and whether or not the actions are blameworthy. Therefore, I believe genetic information could be useful and accurate, improving our legal system. The Brain on the Stand by Rosen somewhat agrees and disagrees with the arguments put forth by both Zimbardo and Eagleman. Rosen agrees with Eagleman’s claim that biology is responsible for our actions. However, Rosen is asking the question of whether or not we should use genetic information in legal situations. “As the new technologies proliferate, even the neurolaw experts themselves have only begun to think about the questions that lie ahead” (Rosen 12). Rosen also claims that “we must instead look to our own powers of reasoning and intuition, relatively primitive as they may be” (12). There is the possibility that using brain scans in court may not even provide accurate evidence. For instance, neuroscience might excuse individuals of responsibility for the evil acts that they have committed; however, it might also blame other people for acts that they have not committed. After reading the perspectives of Zimbardo, Eagleman, and Rosen, I found myself agreeing with a portion of all of their claims. I believe that the legal system should not have access to such personal information. Information about a person’s brain and how they think should be kept private. Therefore, genetic information should not be shared unless the person is willing to. I agree with Rosen on the idea that we need to find a Milner 5 solution that does not involve neurotechnology, but instead is “moral and ultimately legal”. The Lucifer Effect by Philip Zimbardo, Incognito by David Eagleman, and The Brain on the Stand by Jeffrey Rosen all have different approaches towards answering the question of what is the cause of evil behavior and whether or not neuroscience should be used in our legal system. Both Zimbardo and Eagleman provide scientific and statistical evidence for their claims. Zimbardo takes an incrementalist-situationalist approach and claims that our behavior depends on the situation that we are in. Our surrounding environments influence who we are as people and how we act. However, this idea contrasts to Eagleman, who claims that biology is responsible. He brings about the idea that we do not have freewill because we cannot choose our genetics. Rosen questions how the evidence provided by Zimbardo and Eagleman should be used in legal situations. People often assume that neurotechnology is the answer and should be used in court situations. However, Rosen argues that this is intervening too far into one’s personal life and should not be used. Although there is no answer to this underlying question, maybe we should ignore science for once, and try listening to our intuition instead. Milner 6 Works Cited Eagleman, David M. Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain. New York: Pantheon, 2011. Print. Rosen, Jeffrey. “The Brain on the Stand.” The New York Times 11 March 2007: 1–12. Print. Zimbardo, Phillip. The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil. New York: Ransom House, 2007. Print.