About the author

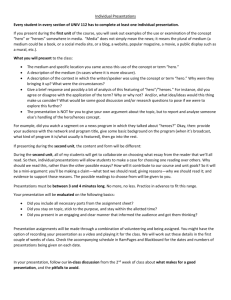

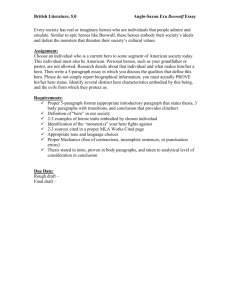

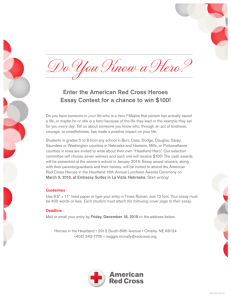

advertisement