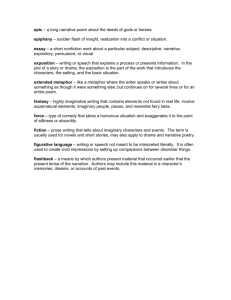

Interactive Narrative

advertisement