encoding: attention and rehearsal

advertisement

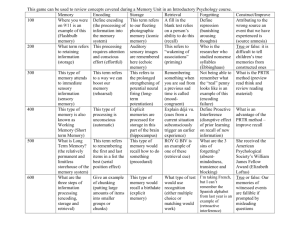

BUILDING MEMORIES I: ATTENTION AND REHEARSAL • Themes – Factors that influence encoding • Presented information • What you do with it • What you know about it • The context of the encoding episode – In general, memory will be influenced by • The quantity of practice • The distribution of practice • The quality of practice – Informal strategies for learning • What do you do? ATTENTION AND LEARNING • The unimportance of being earnest (Hyde & Jenkins, 1969) 24 words presented instructions about recall Encoding task: rate pleasantness detect # of e’s incidental intentional 16.3 16.6 9.4 10.2 • The importance of being awake: • Simons & Emmons (1956) – Word lists presented during sleep – EEG recorded to confirm sleep – Next day: recognition d’ = 0 • Tilley (1979) – 20 pictures of concrete objects shown before sleep – Ten repetitions of object names at different sleep stages – Next day: better recall, recognition of named objects – But only for “shallow” stages of sleep • Walker & Stickgold (2006) – Resurgence of research on “sleepdependent memory processes” • The importance of getting sleep – Sleep deprivation and encoding • Walker & Stickgold 2006: 36 hours of sleep deprivation Incidental study of word lists Recall two days later: – REM deprivation and the brain • Baseline EPSP, LTP down in hippocampus • Nerve growth factor down “ “ • Sleep and Consolidation – Greater activity in REM & SWS • Following intensive study session • Correlates with later retention – Peigneux, et al. (2004): • The importance of paying attention – The classic “shadowing’ studies (e.g., Moray 1959: 35 reps don’t help) – Dual-task studies and divided attention (Murdock, 1965) – Are some attributes of events encoded “automatically”? • Frequency • Recency • Temporal & spatial distribution – (Hasher & Zacks, 1979) • Are these more a function of “implicit memory” than explicit encoding? • Evidence that even these can be influenced by attention, age, etc. AMOUNT OF PRACTICE • Retention increases monotonically with amount of practice – Repetitions across lists (Ebbinghaus, 1885) – Repetitions within list (Rundus, 1971) • The Power Law of Practice log(Y) = a * (log [practice]) + b taking the “antilog” of each side: Y = b * (practice)a – Ubiquitous in declarative and procedural learning – A number of models can generate it – E.g., Estes’ classic Stimulus Sampling Theory (1960’s) DISTRIBUTION OF PRACTICE: THE SPACING EFFECT The robustness of the spaced-practice advantage • Across days – Spanish vocabulary (Bahrick & Phelps (1987) • Two sessions • 0, 1 or 30 days between sessions • Immediate test: no diffs • 8 years later: 30-day is 2.5 times better – Typing Skill (Baddeley & Longman, 1978) • One- or two-hour blocks • One or two blocks per day • Spaced practice group learns twice as fast • Spacing within sessions – The “lag” effect (e.g., Melton 1962) e.g. Underwood (1970): 42 nouns for free recall, one/sec rate 1 to 4 presentations, massed or spaced 1 2 3 massed 15% 17% 17% 19% spaced 31% 42% 47% 16% 4 • Limits to Spacing Advantage – Immediate tests after study – Implicit memory tasks – Very-long lag between presentations • The wonders of “expanded rehearsal” EXPLANATIONS OF THE SPACING EFFECT • Encoding variability and relational processing – Idea: increasing “retrieval paths” – Spacing helps free recall > cued recall – Forcing variability sometimes helps, sometimes hurts, final recall • Deficient attention (and its consequences) – Idea: massed presentations give habituation, less attention and learning e.g., Johnson & Uhle (1976): repeat Underwood (1970), measure “tone probe” secondary task RT: 1 spaced 2 3 4 321 330 328 238 223 206 282 massed • Deficient Rehearsal – Idea: less “covert” rehearsal if massed – Spacing does increase overt rehearsal – Spacing advantage even in incidentalmemory tasks • Deficient Consolidation – Idea: massed practice prevents full consolidation – Can it handle wide “scale” of spacing effects? • Retrieval practice – Idea: spaced study gives “covert retrieval” of prior encounter – Forcing retrieval gives better memory than study only (Carrier & Pashler, 1992) – The Testing Effect (Gates, 1917) • Long-term benefit from testing versus studying Spacing and context • Verkoeijen, Rikers & Schmidt (2004) Ss see 120 words per list 20 single, 20 massed rep, 20 spaced rep Black on white, or olive, background (E1) Black on city, or forest, background (E2) 40 Percent Recalled – – – – 35 same background 30 different background 25 20 15 10 5 0 spaced massed Type of practice single The Power of Testing Memory • Retrieval practice’s advantages – “If you read a piece of text through twenty times, you will not learn it by heart so easily as if you read it ten times while attempting to recite it from time to time, and consulting the text when memory fails” (Francis Bacon, 1620) – Roediger & Karpicke (2006) • Students study scientific prose • Then restudy for 7 min, vs. free recall, no feedback • Final recall at 5 min, 2 days, 1 week Proportion idea units recalled 90 80 Study, Study 70 Study, Test 60 50 40 30 20 5 min 2 days Retention interval 1 week