Michael Potter BL - PCO NI Caselaw

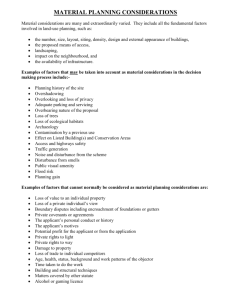

advertisement