Memory - Images

advertisement

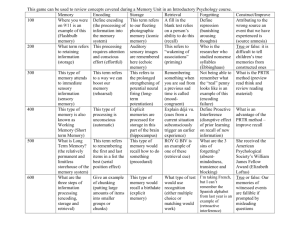

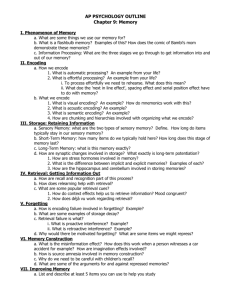

Retrieval is the process of getting information out of memory storage. Retrieval includes recall, which is the ability to retrieve information not in conscious awareness, something previously learned. Example: fill in the blank questions Retrieval also includes recognition, which is the ability to identify items previously learned. Example: multiple choice test questions Retrieval also includes a measure of how quickly you can relearn previously learned material Harry Bahrick (1975) reported that people who had graduated 25 years earlier could not recall many of their classmates, but they could recognize 90 percent of their pictures and names. Our recognition memory is very quick and vast. We can recognize many things without even thinking. Your memories are woven like a web of associations with all your memories interconnected. When you encode a piece of information(target information), it is associated with other bits of information. These bits of information are called retrieval cues. Retrieval cues are points that you can use to anchor and access the target information at a later time. What can be a retrieval cue? Visual images, mnemonic devices, associations we form involving taste, smell, sights, sounds, etc. Priming is the awakening of associations, often unconsciously, in our memory Priming can be memoryless memory— invisible memory without explicit remembering. In a study by Duncan Godden and Alan Baddeley (1975), showed that we can recall information better if it is retested in the same location that we learned it. They had scuba divers listen to a list of words in two different settings, either under water or on a beach. When tested on their recall of the words the divers performed better if in the same setting. The percentages of recall were as follows: Land/water 21% Water/land 22% Water/water 31% Land/land 39% Even infants as young as 3 months old can be impacted by context effects. Carolyn Rovee-Collier (1993), performed several experiments with infants. In one particular study, the infants were placed in a crib with a mobile. They were connected to the mobile via a ribbon attached to their ankles. This allowed the infant to move the mobile by themselves. The infants kicked more when retested in the same crib, with the same bumper than when in a different context. Déjà vu is the sense that you have experienced something before. Cues from the current experience may trigger retrieval of an earlier experience. In a study by Brown in 2003, it was determined that although it happens to many of us it is more common in young, well educated adults especially when they are under stress. So why does déjà vu happen? It may be that your current situation is full of memory cues that unconsciously retrieve an old memory of a earlier, similar event. Much of the information that your brain takes in is without your awareness and you often forget where the information in your memory came from. So, the current situation may stir up memories that cause you to believe that you have had this experience before. It could also be that a situation seems familiar when moderately similar to several events (Lampinen,2002). Another theory, attributes déjà vu to our dual processing system. The basic premise is that your processing of information is occurring on multiple levels or tracks at the same time. If one level or track were to be delayed, it seems as though we are reexperiencing the event (Brown,2004b). Our moods or states of being may impact our ability to retrieve memories. State-dependent memory is a phenomenon that you best remember something if you are in the same state as you were when you learned it. Mood states provide an example of this phenomenon. Emotions that accompany good or bad events can become retrieval cues. Our memories are somewhat moodcongruent: the tendency to recall experiences that are consistent with one’s current mood state. Studies show that being in a bad mood may facilitate recalling other bad times. Being depressed primes negative associations, which then are used to explain our current mood. People currently suffering from depression are more likely to recall their parents as rejecting, guilt-promoting and punitive, while formerly depressed persons are more likely to recall as do people who have never had depression(Lewinsohn & Rosenbaum, 1987). In a study of adolescents in 1991, Bornstein found that teens view their parents differently dependent upon mood. Ratings of parental warmth varied greatly from one week to a new rating after six weeks. The ratings seemed dependent upon the mood state of the teen. We are often upset about our failures of memory. We are amazed at great feats of memory and we seek to improve our own memory. But what about forgetting? Is there any reason to praise forgetting and why does forgetting occur? Some memory whizzes admit that their brains are so full of trivial memory that they cannot think. One such whiz, Shereshevskii (known as S.)could memorize a story but could not summarize its main points or meaning. There was so much in his memory that he could not summarize, generalize or think abstractly. Another example that points to the positives of forgetting is the case of A.J., identified as Jill Price. Jill has the ability to recall every day of her life since she was 14 with amazing clarity. She can remember dates, where she was and what was said or what occurred. This has been documented through a study at UC at Irvine. She states that it is exhausting to live in the present and the past at the same time. Daniel Schacter (1999) has listed the seven ways our memories fail us. He calls them the seven sins of memory. Three sins of forgetting: Absent-mindedness: inattention to detail leads to forgetting Transience: storage decay over time Blocking: inaccessibility of stored information Three sins of distortion: Misattribution: confusing the source of the information Suggestibility: the lingering effects of misinformation Bias: belief colored recollections One sin of intrusion: Persistence: unwanted memories Encoding failure is a process of age. As we age the parts of the brain that encode information work less efficiently. This leads to a general age related memory decline. Encoding failure also occurs because our brains are bombarded with so much information that we cannot possibly encode it all. We selectively attend to only a few of the many pieces of information. How many details can you recall concerning the a penny? Could you identify a real penny in a penny line-up? In a study(1979), Nickerson and Adams discovered that most people cannot identify the real penny. When asked, spontaneously without prompting, most people could only recall three of the eight critical features. Why? The features of the penny are not crucial to us, so unless we have made an effort to encode them, it is unlikely that we will recall them. (effortful processing) Ebbinghaus created the forgetting curve during his experiment on learning novel verbal information. The forgetting curve has been supported by other later experiments. The forgetting curve shows that the course of forgetting is initially rapid but levels off over time. Henry Bahrick (1984) studied the forgetting curve for people who learned Spanish in high school. Compared with people who had just completed a course in Spanish, people three years out of school had forgotten much of what they had learned. However, what people knew at three years out, they still remembered 25 years later. Their forgetting had leveled off. Why does the forgetting curve look as it does? One explanation is the gradual fading of a physical memory trace. Cognitive neuroscientists are still investigating the physical storage of memory and daily our understanding of how storage decay could occur is increasing. Another theory is that the accumulation of learning disrupts our ability to retrieve information previously encoded. Retrieval failure can be about: 1) memories never encoded 2) memories that were discarded(storage decay) 3) inaccessible because we do not have enough information to look it up (tip of the tongue), the memory is there but we may need retrieval cues to be able to retrieve it Interference refers to the situation where learning one item may interfere with your ability to retrieve another item from your memory. Proactive interference (forward-acting) occurs when something you learned earlier disrupts your ability to recall something you experience later. For example if you get a new phone number, you memory of the earlier number may interfere with your ability to recall the new number. Your brain’s capacity to remember is vast and unfillable but it can become cluttered with unnecessary information. Focus is aided by tuning out the clutter. In this case forgetting would be adaptive. Retroactive interference (backward-acting) occurs when learning new information makes it more difficult to remember previously learned information. Information learned before sleep is protected from retroactive interference because the opportunity for any interference is limited. Dallenbach and Jenkins (1924), studied this concept. They gave participants random syllables to learn. Some followed learning with 8 hours of sleep, some with 8 hours of awake. Forgetting was more common in the awake state. The researchers believed that this was due to interference from events that occurred while awake. Other studies have confirmed that an hour before sleep is a good time to commit new information to memory. Interference is a real reason why we may forget certain information. However, previous knowledge can be beneficial. It is called positive transfer. For example, knowing Latin may help you learn French. Interference occurs when the old and the new compete. Memory can be an unreliable, selfserving historian. (Tavris & Aronson, 2007) We often unknowingly revise our history. In 1981, Ross and colleagues found that people who had been told the benefits of tooth brushing recalled (more than others) frequently brushing their teeth in the previous two week period. Why do our memories fail us? It could be a failure to encode, or a storage problem, or an inability to retrieve. But some, including Freud, would argue that some memories are repressed. Freud believed that we repress memories in order to preserve our self-concept or to minimize anxiety. Efforts to intentionally forget neutral events are often successful, but it is difficult to forget emotional information, which is why traumatic events often intrude upon our memory even when we try to forget. Although many believe that repression of memory occurs, large and growing numbers of memory researchers say that it rarely does.