Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org

Response to Intervention

RTI: Issues in Math

Assessment

Jim Wright www.interventioncentral.org

www.interventioncentral.org

Response to Intervention

Evaluation. “the process of using information collected through assessment to make decisions or reach conclusions.” (Hosp, 2008; p. 364).

Example: A student can be evaluated for problems in ‘fluency with text’ by collecting information using various sources (e.g., CBM ORF, teacher interview, direct observations of the student reading across settings, etc.), comparing those results to peer norms or curriculum expectations, and making a decision about whether the student’s current performance is acceptable.

Assessment. “the process of collecting information about the characteristics of persons or objects by measuring them. ” (Hosp, 2008; p. 364).

Example: The construct ‘fluency with text’ can be assessed using various measurements, including CBM ORF, teacher interview, and direct observations of the student reading in different settings and in different material.

Measurement. “the process of applying numbers to the characteristics of objects or people in a systematic way” (Hosp, 2008; p. 364).

Example: Curriculum-Based Measurement Oral Reading Fluency (CBM ORF) is one method to measure the construct ‘fluency with text’ www.interventioncentral.org

2

Response to Intervention

Use Time & Resources Efficiently By Collecting Information

Only on ‘Things That Are Alterable’

“…Time should be spent thinking about things that the intervention team can influence through instruction, consultation, related services, or adjustments to the student’s program. These are things that are alterable.…Beware of statements about cognitive processes that shift the focus from the curriculum and may even encourage questionable educational practice. They can also promote writing off a student because of the rationale that the student’s insufficient

Psychologists.

performance is due to a limited and fixed potential. “ p.359

3

Response to Intervention

Formal Tests: Only One Source of Student Assessment

Information

“Tests are often overused and misunderstood in and out of the field of school psychology.

When necessary, analog [i.e., test] observations can be used to test relevant hypotheses within controlled conditions.

Testing is a highly standardized form of observation. ….The only reason to administer a test is to answer well-specified questions and examine well-specified hypotheses. It is best practice to identify and make explicit the most relevant questions before assessment begins.

…The process of assessment should follow these questions. The questions should not www.interventioncentral.org

follow assessment. “ p.170

4

Response to Intervention

RIOT/ICEL Framework

www.interventioncentral.org

Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org

Response to Intervention

RIOT/ICEL Framework

Sources of Information

• Review (of records)

• Interview

• Observation

• Test

Focus of Assessment

• Instruction

• Curriculum

• Environment

• Learner www.interventioncentral.org

7

Response to Intervention

RIOT/ICEL Definition

• The RIOT/ICEL matrix is an assessment guide to help schools efficiently to decide what relevant information to collect on student academic performance and behavior—and also how to organize that information to identify probable reasons why the student is not experiencing academic or behavioral success.

• The RIOT/ICEL matrix is not itself a data collection instrument. Instead, it is an organizing framework, or heuristic, that increases schools’ confidence both in the quality of the data that www.interventioncentral.org

they collect and the findings that emerge from

8

Response to Intervention

RIOT: Sources of Information

• Select Multiple Sources of Information: RIOT

(Review, Interview, Observation, Test). The top horizontal row of the RIOT/ICEL table includes four potential sources of student information: Review, Interview, Observation, and

Test (RIOT). Schools should attempt to collect information from a range of sources to control for potential bias from any one source. www.interventioncentral.org

9

Response to Intervention

• Review. This category consists of past or present records collected on the student. Obvious examples include report cards, office disciplinary referral data, state test results, and attendance records. Less obvious examples include student work samples, physical products of teacher interventions (e.g., a sticker chart used to reward positive student behaviors), and emails sent by a teacher to a parent detailing concerns about a student’s study and organizational skills.

www.interventioncentral.org

10

Response to Intervention

• Interview. Interviews can be conducted face-to-face, via telephone, or even through email correspondence. Interviews can also be structured

(that is, using a pre-determined series of questions) or follow an open-ended format, with questions guided by information supplied by the respondent.

Interview targets can include those teachers, paraprofessionals, administrators, and support staff in the school setting who have worked with or had interactions with the student in the present or past.

Prospective interview candidates can also consist of www.interventioncentral.org

parents and other relatives of the student as well as 11

Response to Intervention

• Observation. Direct observation of the student’s academic skills, study and organizational strategies, degree of attentional focus, and general conduct can be a useful channel of information. Observations can be more structured (e.g., tallying the frequency of call-outs or calculating the percentage of on-task intervals during a class period) or less structured

(e.g., observing a student and writing a running narrative of the observed events). www.interventioncentral.org

12

Response to Intervention

• Test. Testing can be thought of as a structured and standardized observation of the student that is intended to test certain hypotheses about why the student might be struggling and what school supports would logically benefit the student (Christ,

2008). An example of testing may be a student being administered a math computation CBM probe or an Early Math Fluency probe.

www.interventioncentral.org

13

Response to Intervention

ICEL: Factors Impacting Student Learning

• Investigate Multiple Factors Affecting

Student Learning: ICEL (Instruction,

Curriculum, Environment, Learner). The leftmost vertical column of the RIO/ICEL table includes four key domains of learning to be assessed: Instruction, Curriculum, Environment, and Learner (ICEL). A common mistake that schools often make is to assume that student learning problems exist primarily in the learner and to underestimate the degree to which teacher instructional strategies, curriculum www.interventioncentral.org

the learner’s academic performance. The ICEL

14

Response to Intervention

• Instruction. The purpose of investigating the

‘instruction’ domain is to uncover any instructional practices that either help the student to learn more effectively or interfere with that student’s learning.

More obvious instructional questions to investigate would be whether specific teaching strategies for activating prior knowledge better prepare the student to master new information or whether a student benefits optimally from the large-group lecture format that is often used in a classroom. A less obvious example of an instructional question would be www.interventioncentral.org

whether a particular student learns better through 15

Response to Intervention

• Curriculum. ‘Curriculum’ represents the full set of academic skills that a student is expected to have mastered in a specific academic area at a given point in time. To adequately evaluate a student’s acquisition of academic skills, of course, the educator must (1) know the school’s curriculum (and related state academic performance standards), (2) be able to inventory the specific academic skills that the student currently possesses, and then (3) identify gaps between curriculum expectations and actual student skills. (This process of uncovering student www.interventioncentral.org

academic skill gaps is sometimes referred to as 16

Response to Intervention

• Environment. The ‘environment’ includes any factors in the student’s school, community, or home surroundings that can directly enable their academic success or hinder that success. Obvious questions about environmental factors that impact learning include whether a student’s educational performance is better or worse in the presence of certain peers and whether having additional adult supervision during a study hall results in higher student work productivity. Less obvious questions about the learning environment include whether a student has a setting at home that is conducive to completing delaying that student’s transitioning between classes

17

Response to Intervention

• Learner. While the student is at the center of any questions of instruction, curriculum, and [learning] environment, the ‘learner’ domain includes those qualities of the student that represent their unique capacities and traits. More obvious examples of questions that relate to the learner include investigating whether a student has stable and high rates of inattention across different classrooms or evaluating the efficiency of a student’s study habits and test-taking skills. A less obvious example of a question that relates to the learner is whether a student harbors a low sense of self-efficacy in willingness to put appropriate effort into math

18

Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org

Response to Intervention

• The teacher collects several student math computation worksheet samples to document the child’s illegible number formation.

• Data Source: Review

• Focus Areas: Curriculum www.interventioncentral.org

20

Response to Intervention

• The student’s parent tells the teacher that her son’s math grades dropped suddenly back in 4 th grade.

• Data Source: Interview

• Focus: Curriculum www.interventioncentral.org

21

Response to Intervention

• An observer monitors the student’s attention on an independent math work assignment—and later analyzes the work’s quality and completeness.

• Data Sources:

Observation, Review

• Focus Areas:

Curriculum,

Environment, Learner www.interventioncentral.org

22

Response to Intervention

• A student is given a timed math worksheet to complete. She is then given another timed worksheet & offered a reward if she improves.

• Data Source: Review,

Test

• Focus Areas:

Curriculum, Learner www.interventioncentral.org

23

Response to Intervention

• Comments from several past report cards describe the student as preferring to socialize rather than work during small-group math activities.

• Data Source: Review

• Focus Areas:

Environment www.interventioncentral.org

24

Response to Intervention

• The teacher tallies the number of redirects for an off-task student during math. She designs a highinterest lesson, still tracks off-task behavior.

• Data Source:

Observation, Test

• Focus Areas: Instruction www.interventioncentral.org

25

Response to Intervention

Activity: Use the RIOT/ICEL Framework

• Review the RIOT/ICEL matrix. Brainstorm sources of data that could be used to fill in the matrix to collect a range of information about students with math difficulties in your school.

www.interventioncentral.org

26

Response to Intervention

Evaluating the ‘RTI

Readiness’ of School

Assessments

Jim Wright www.interventioncentral.org

www.interventioncentral.org

Response to Intervention

RTI Literacy: Assessment & Progress-Monitoring

The RTI model collects math assessment information on students on a schedule based on their risk profile and intervention placement.

Math assessment measures used are valid, reliable, brief, and matched to curriculum expectations for each grade.

Source: Burns, M. K., & Gibbons, K. A. (2008). Implementing response-to-intervention in elementary and secondary schools:

Procedures to assure scientific-based practices. New York: Routledge. www.interventioncentral.org

28

Response to Intervention

RTI Literacy: Assessment & Progress-Monitoring

(Cont.)

To measure student ‘response to instruction/intervention’ effectively, the RTI Literacy model measures students’ reading performance and progress on schedules matched to each student’s risk profile and intervention Tier membership.

• Benchmarking/Universal Screening. All children in a grade level are assessed at least 3 times per year on a common collection of literacy assessments.

• Strategic Monitoring. Students placed in Tier 2 (supplemental) reading groups are assessed 1-2 times per month to gauge their progress with this intervention.

• Intensive Monitoring. Students who participate in an intensive, individualized Tier 3 reading intervention are assessed at least once per week.

Source: Burns, M. K., & Gibbons, K. A. (2008). Implementing response-to-intervention in elementary and secondary schools:

Procedures to assure scientific-based practices. New York: Routledge. www.interventioncentral.org

29

Response to Intervention

Curriculum-Based Measurement: Advantages as a Set of Tools to

Monitor RTI/Academic Cases

• Aligns with curriculum-goals and materials

• Is reliable and valid (has ‘technical adequacy’)

• Is criterion-referenced: sets specific performance levels for specific tasks

• Uses standard procedures to prepare materials, administer, and score

• Samples student performance to give objective, observable ‘low-inference’

information about student performance

• Has decision rules to help educators to interpret student data and make appropriate instructional decisions

• Is efficient to implement in schools (e.g., training can be done quickly; the measures are brief and feasible for classrooms, etc.)

• Provides data that can be converted into visual displays for ease of communication

Source: Hosp, M.K., Hosp, J. L., & Howell, K. W. (2007). The ABCs of CBM. New York: Guilford.

www.interventioncentral.org

30

Response to Intervention

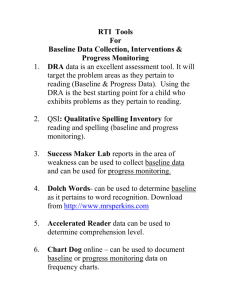

CBM Math Measures: Selected Sources

• AimsWeb (http://www.aimsweb.com)

• Easy CBM (http://www.easycbm.com)

• iSteep (http://www.isteep.com)

• EdCheckup (http://www.edcheckup.com)

• Intervention Central (http://www.interventioncentral.org) www.interventioncentral.org

31

Response to Intervention

CBM: Developing a

Process to Collect

Local Norms

Jim Wright www.interventioncentral.org

www.interventioncentral.org

Response to Intervention

RTI Literacy: Assessment & Progress-Monitoring

To measure student ‘response to instruction/intervention’ effectively, the RTI model measures students’ academic performance and progress on schedules matched to each student’s risk profile and intervention Tier membership.

• Benchmarking/Universal Screening. All children in a grade level are assessed at least 3 times per year on a common collection of academic assessments.

• Strategic Monitoring. Students placed in Tier 2 (supplemental) reading groups are assessed 1-2 times per month to gauge their progress with this intervention.

• Intensive Monitoring. Students who participate in an intensive, individualized Tier 3 intervention are assessed at least once per week.

Source: Burns, M. K., & Gibbons, K. A. (2008). Implementing response-to-intervention in elementary and secondary schools:

Procedures to assure scientific-based practices. New York: Routledge. www.interventioncentral.org

33

Response to Intervention

Local Norms: Screening All Students

(Stewart & Silberglit,

2008)

Local norm data in basic academic skills are collected at least 3 times per year (fall, winter, spring).

• Schools should consider using ‘curriculum-linked’ measures such as Curriculum-Based Measurement that will show generalized student growth in response to learning.

• If possible, schools should consider avoiding

‘curriculum-locked’ measures that are tied to a single commercial instructional program.

Source: Stewart, L. H. & Silberglit, B. (2008). Best practices in developing academic local norms. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes

(Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V (pp. 225-242). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists.

www.interventioncentral.org

34

Response to Intervention

Local Norms: Using a Wide Variety of Data

(Stewart & Silberglit, 2008)

Local norms can be compiled using:

• Fluency measures such as Curriculum-Based

Measurement.

• Existing data, such as office disciplinary referrals.

• Computer-delivered assessments, e.g., Measures of

Academic Progress (MAP) from www.nwea.org

Source: Stewart, L. H. & Silberglit, B. (2008). Best practices in developing academic local norms. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes

(Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V (pp. 225-242). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists.

www.interventioncentral.org

35

Measures of

Academic Progress

(MAP) www.nwea.org

Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org

36

Response to Intervention

Applications of Local Norm Data

(Stewart & Silberglit, 2008)

Local norm data can be used to:

• Evaluate and improve the current core instructional program.

• Allocate resources to classrooms, grades, and buildings where student academic needs are greatest.

• Guide the creation of targeted Tier 2

(supplemental intervention) groups

• Set academic goals for improvement for students on Tier 2 and Tier 3 interventions.

• Move students across levels of intervention, based on performance relative to that of peers

(local norms).

37

Response to Intervention

Local Norms: Supplement With Additional

Academic Testing as Needed

(Stewart & Silberglit, 2008)

“ At the individual student level, local norm data are just the first step toward determining why a student may be experiencing academic difficulty. Because local norms are collected on brief indicators of core academic skills, other sources of information and additional testing using the local norm measures or other tests are needed to validate the problem and determine why the student is having difficulty. … Percentage correct and rate information provide clues regarding automaticity and accuracy of skills. Error types, error patterns, and qualitative data provide clues about how a student approached the task. Patterns of strengths and weaknesses on subtests of an assessment can provide information about the concepts in which a student or group of students may need greater instructional support, provided these subtests are equated and reliable for these purposes.” p. 237

Source: Stewart, L. H. & Silberglit, B. (2008). Best practices in developing academic local norms. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes

(Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V (pp. 225-242). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists.

www.interventioncentral.org

38

Response to Intervention

Formative Assessment Overview:

Specific Assessment Tools to

Measure Student Math Skills

Jim Wright www.interventioncentral.org

www.interventioncentral.org

Response to Intervention

School Instructional Time: The Irreplaceable Resource

“In the average school system, there are 330 minutes in the instructional day, 1,650 minutes in the instructional week, and 56,700 minutes in the instructional year. Except in unusual circumstances, these are the only minutes we have to provide effective services for students. The number of years we have to apply these minutes is fixed. Therefore, each minute counts and schools cannot afford to support inefficient models of service delivery.” p. 177

Source: Batsche, G. M., Castillo, J. M., Dixon, D. N., & Forde, S. (2008). Best practices in problem analysis. In A. Thomas & J.

Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V (pp. 177-193).

www.interventioncentral.org

40

Response to Intervention

Effective Formative Evaluation: The Underlying Logic…

1. What is the relevant academic or behavioral outcome measure to be tracked?

2. Is the focus the core curriculum or system, subgroups of underperforming learners, or individual struggling students?

3. What method(s) should be used to measure the target academic skill or behavior?

4. What goal(s) are set for improvement?

5. How does the school check up on progress toward the goal(s)?

www.interventioncentral.org

Response to Intervention

Summative data is static information that provides a fixed ‘snapshot’ of the student’s academic performance or behaviors at a particular point in time. School records are one source of data that is often summative in nature—frequently referred to as archival data.

Attendance data and office disciplinary referrals are two examples of archival records, data that is routinely collected on all students.

In contrast to archival data, background information is collected specifically on the target student. Examples of background information are teacher interviews and student interest surveys, each of which can shed light on a student’s academic or behavioral strengths and weaknesses. Like archival data, background information is usually summative, providing a measurement of the student at a single point in time. www.interventioncentral.org

42

Response to Intervention

Formative assessment measures are those that can be administered or collected frequently—for example, on a weekly or even daily basis.

These measures provide a flow of regularly updated information

(progress monitoring) about the student’s progress in the identified area(s) of academic or behavioral concern.

Formative data provide a ‘moving picture’ of the student; the data unfold through time to tell the story of that student’s response to various classroom instructional and behavior management strategies.

Examples of measures that provide formative data are Curriculum-

Based Measurement probes in oral reading fluency and Daily Behavior

Report Cards. www.interventioncentral.org

43

Response to Intervention

Formal Assessment Defined

“Formative assessment [in academics] refers to the gathering and use of information about students’ ongoing learning by both teachers and students to

modify teaching and learning activities. ….

Today…there are compelling research results indicating that the practice of formative assessment may be the most significant single factor in raising the academic achievement of all students—and especially that of lower-achieving students.” p. 7

Source: Harlen, W. (2003). Enhancing inquiry through formative assessment. San Francisco, CA: Exploratorium. Retrieved on

September 17, 2008, from http://www.exploratorium.edu/ifi/resources/harlen_monograph.pdf

www.interventioncentral.org

44

Response to Intervention

Academic or Behavioral Targets Are Stated as

‘Replacement Behaviors’

“ A problem solution is defined as one or more changes to the instruction, curriculum, or environment that function(s) to reduce or eliminate a problem.

” p. 159

Source: Christ, T. (2008). Best practices in problem analysis. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V (pp. 159-176).

www.interventioncentral.org

45

Response to Intervention

Formative Assessment: Essential Questions…

1. What is the relevant academic or behavioral outcome measure to be tracked?

Problems identified for formative assessment should be:

1. Important to school stakeholders.

2. Measureable & observable.

3. Stated positively as ‘replacement behaviors’ or goal statements rather than as general negative concerns

(Bastche et al., 2008).

4. Based on a minimum of inference

(T. Christ, 2008).

Source: Batsche, G. M., Castillo, J. M., Dixon, D. N., & Forde, S. (2008). Best practices in problem analysis. In A. Thomas & J.

Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V (pp. 177-193).

Christ, T. (2008). Best practices in problem analysis. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V

(pp. 159-176).

www.interventioncentral.org

46

Response to Intervention

Inference: Moving Beyond the Margins of the ‘Known’

“An inference is a tentative conclusion without direct or conclusive support from available data. All hypotheses are, by definition, inferences. It is critical that problem analysts make distinctions between what is known and what is inferred or hypothesized….Low-level inferences should be exhausted prior to the use of high-level inferences.” p. 161

Source: Christ, T. (2008). Best practices in problem analysis. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V (pp. 159-176).

www.interventioncentral.org

47

Response to Intervention

Examples of High vs. Low Inference Hypotheses

The results of grade-wide benchmarking in math computation show that a target 2 nd -grade student computes math facts (‘double-digit subtraction without regrouping’) at approximately half the rate of the median child in the grade.

High-Inference Hypothesis.

The student has visual processing and memory issues that prevent him or her from proficiently solving math facts. The student requires a multisensory approach such as TouchMath to master the math facts.

Unknown

Known

Unknown

Low-Inference Hypothesis.

The student has acquired the basic academic skill but needs to build fluency. The student will benefit from repeated opportunities to practice the skill with performance feedback about both accuracy and fluency (e.g., Explicit

Time Drill). .

www.interventioncentral.org

Known

48

Response to Intervention

Adopting a Low-Inference Model of Math Skills

5 Strands of Mathematical Proficiency

1. Understanding

2. Computing

3. Applying

4. Reasoning

5. Engagement

Source: National Research Council. (2002). Helping children learn mathematics. Mathematics Learning Study Committee, J.

Kilpatrick & J. Swafford, Editors, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education.

Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

www.interventioncentral.org

49

Response to Intervention

Formative Assessment: Essential Questions…

2. Is the focus the core curriculum or system, subgroups of underperforming learners, or individual struggling students?

Apply the ‘80-15-5 ‘Rule

(T. Christ, 2008)

:

– If less than 80% of students are successfully meeting academic or behavioral goals, the formative assessment focus is on the core curriculum and general student population.

– If no more than 15% of students are not successful in meeting academic or behavioral goals, the formative assessment focus is on small-group ‘treatments’ or interventions.

– If no more than 5% of students are not successful in meeting academic or behavioral goals, the formative assessment focus is on the individual student.

Source: Christ, T. (2008). Best practices in problem analysis. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V (pp. 159-176).

www.interventioncentral.org

50

Response to Intervention

Formative Assessment: Essential Questions…

3. What method(s) should be used to measure the target academic skill or behavior?

Formative assessment methods should be as direct a measure as possible of the problem or issue being evaluated. These assessment methods can:

– Consist of General Outcome Measures or Specific Sub-Skill

Mastery Measures

– Include existing (‘extant’) data from the school system

Curriculum-Based Measurement (CBM) is widely used to track basic student academic skills. Daily Behavior Report Cards (DBRCs) are increasingly used as one source of formative behavioral data.

Source: Burns, M. K., & Gibbons, K. A. (2008). Implementing response-to-intervention in elementary and secondary schools:

Procedures to assure scientific-based practices. New York: Routledge. www.interventioncentral.org

51

Response to Intervention

Making Use of Existing (‘Extant’) Data

www.interventioncentral.org

Response to Intervention

Extant (Existing) Data

(Chafouleas et al., 2007)

• Definition: Information that is collected by schools as a matter of course.

• Extant data comes in two forms:

– Performance summaries (e.g., class grades, teacher summary comments on report cards, state test scores).

– Student work products (e.g., research papers, math homework, PowerPoint presentation).

Source: Chafouleas, S., Riley-Tillman, T.C., & Sugai, G. (2007). School-based behavioral assessment: Informing intervention

and instruction. New York: Guilford Press.

www.interventioncentral.org

53

Response to Intervention

Advantages of Using Extant Data

(Chafouleas et al., 2007)

• Information is already existing and easy to access.

• Students will not show ‘reactive’ effects when data is collected, as the information collected is part of the normal routine of schools.

• Extant data is ‘relevant’ to school data consumers (such as classroom teachers, administrators, and members of problem-solving teams).

Source: Chafouleas, S., Riley-Tillman, T.C., & Sugai, G. (2007). School-based behavioral assessment: Informing intervention

and instruction. New York: Guilford Press.

www.interventioncentral.org

54

Response to Intervention

Drawbacks of Using Extant Data

(Chafouleas et al., 2007)

• Time is required to collate and summarize the data (e.g., summarizing a week’s worth of disciplinary office referrals).

• The data may be limited and not reveal the full dimension of the student’s presenting problem(s).

• There is no guarantee that school staff are consistent and accurate in how they collect the data (e.g., grading policies can vary across classrooms; instructors may have differing expectations regarding what types of assignments are given a formal grade; standards may fluctuate across teachers for filling out disciplinary referrals).

• Little research has been done on the ‘psychometric adequacy’ of extant data sources.

Source: Chafouleas, S., Riley-Tillman, T.C., & Sugai, G. (2007). School-based behavioral assessment: Informing intervention

and instruction. New York: Guilford Press.

www.interventioncentral.org

55

Response to Intervention

Curriculum-Based Measurement: Assessing Basic

Academic Skills www.interventioncentral.org

Response to Intervention

Curriculum-Based Assessment: Advantages Over

Commercial, Norm-Referenced Achievement Tests www.interventioncentral.org

Response to Intervention

Commercial Tests: Limitations

• Compare child to ‘national’ average rather than to class or school peers

• Have unknown overlap with student curriculum, classroom content

• Can be given only infrequently

• Are not sensitive to short-term student gains in academic skills www.interventioncentral.org

58

Response to Intervention

Curriculum-Based Measurement/ Assessment: Defining

Characteristics:

• Assesses preselected objectives from local curriculum

• Has standardized directions for administration

• Is timed, yielding fluency, accuracy scores

• Uses objective, standardized, ‘quick’ guidelines for scoring

• Permits charting and teacher feedback

Source: Wright, J. (1992). Curriculum-based measurement: A manual for teachers. Retrieved on September 4, 2008, from http://www.jimwrightonline.com/pdfdocs/cbaManual.pdf

www.interventioncentral.org

59

Response to Intervention

CBM Techniques have been developed to assess:

• Reading fluency

• Reading comprehension

• Math computation

• Writing

• Spelling

• Phonemic awareness skills

• Early math skills

www.interventioncentral.org

60

Response to Intervention

Measuring General vs. Specific Academic

Outcomes

• General Outcome Measures: Track the student’s increasing proficiency on general curriculum goals such as reading fluency. An example is

CBM-Oral Reading Fluency (Hintz et al., 2006).

• Specific Sub-Skill Mastery Measures: Track short-term student academic progress with clear criteria for mastery (Burns & Gibbons, 2008) . An example is Letter Identification.

Sources: Burns, M. K., & Gibbons, K. A. (2008). Implementing response-to-intervention in elementary and secondary schools:

Procedures to assure scientific-based practices. New York: Routledge.

Hintz, J. M., Christ, T. J., & Methe, S. A. (2006). Curriculum-based assessment. Psychology in the Schools, 43, 45-56.

www.interventioncentral.org

61

Response to Intervention

CBM Math Computation Probes:

Preparation

www.interventioncentral.org

62

Response to Intervention

CBM Math Computation Sample Goals

• Addition: Add two one-digit numbers: sums to 18

• Addition: Add 3-digit to 3-digit with regrouping from ones column only

• Subtraction: Subtract 1-digit from 2-digit with no regrouping

• Subtraction: Subtract 2-digit from 3-digit with regrouping from ones and tens columns

• Multiplication: Multiply 2-digit by 2-digit-no regrouping

• Multiplication: Multiply 2-digit by 2-digit with regrouping www.interventioncentral.org

63

Response to Intervention

CBM Math Computation

Assessment: Preparation

• Select either single-skill or multiple-skill math probe format.

• Create student math computation worksheet (including enough problems to keep most students busy for 2 minutes)

• Create answer key www.interventioncentral.org

64

Response to Intervention

CBM Math Computation

Assessment: Preparation

• Advantage of single-skill probes:

– Can yield a more ‘pure’ measure of student’s computational fluency on a particular problem type www.interventioncentral.org

65

Response to Intervention

CBM Math Computation

Assessment: Preparation

• Advantage of multiple-skill probes:

– Allow examiner to gauge student’s adaptability

between problem types (e.g., distinguishing operation signs for addition, multiplication problems)

– Useful for including previously learned computation problems to ensure that students retain knowledge.

www.interventioncentral.org

66

Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org

67

Response to Intervention

CBM Math Computation Probes:

Administration

www.interventioncentral.org

68

Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org

69

Response to Intervention

CBM Math Computation Probes:

Scoring

www.interventioncentral.org

70

Response to Intervention

CBM Math Computation

Assessment: Scoring

Unlike more traditional methods for scoring math computation problems, CBM gives the student credit for each correct digit in the answer. This approach to scoring is more sensitive to short-term student gains and acknowledges the child’s partial competencies in math.

www.interventioncentral.org

71

Response to Intervention

Math Computation: Scoring Examples

2 CDs

12 CDs www.interventioncentral.org

Response to Intervention

Math Computation: Scoring www.interventioncentral.org

Response to Intervention

Question: How can a school use CBM Math Computation probes if students are encouraged to use one of several methods to solve a computation problem—and have no fixed algorithm?

Answer: Students should know their ‘math facts’ automatically. Therefore, students can be given math computation probes to assess the speed and fluency of basic math facts—even if their curriculum encourages a variety of methods for solving math computation problems. www.interventioncentral.org

74

Response to Intervention

Math Worksheet Generator http://www.interventioncentral.com/htmdocs/tools/mathprobe/addsing.php

www.interventioncentral.org

75

Response to Intervention

Example of CBM Statewide Norms: Math Computation

Source: North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. Retreived on October 1, 2008, from http://www.ncpublicschools.org/ec/development/learning/responsiveness/rtimaterials www.interventioncentral.org

76

Response to Intervention

Source: North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. Retreived on October 1, 2008, from http://www.ncpublicschools.org/ec/development/learning/responsiveness/rtimaterials www.interventioncentral.org

77

Response to Intervention

The application to create CBM Early Math

Fluency probes online http://www.interventioncentral.org/php/numberfly/ numberfly.php

www.interventioncentral.org

Response to Intervention

Examples of Early Math Fluency

(Number Sense) CBM Probes

Quantity Discrimination

Missing Number

Number Identification

Sources: Clarke, B., & Shinn, M. (2004). A preliminary investigation into the identification and development of early mathematics curriculum-based measurement. School Psychology Review, 33, 234–248.

Chard, D. J., Clarke, B., Baker, S., Otterstedt, J., Braun, D., & Katz, R. (2005). Using measures of number sense to screen for difficulties in mathematics: Preliminary findings. Assessment For Effective Intervention, 30(2), 3-14 www.interventioncentral.org

79

Response to Intervention www.interventioncentral.org

Response to Intervention

Math Vocabulary Probes

www.interventioncentral.org

81

Response to Intervention

Curriculum-Based Evaluation: Math Vocabulary

Format Option 1

• 20 vocabulary terms appear alphabetically in the right column. Items are drawn randomly from a ‘vocabulary pool’

• Randomly arranged definitions appear in the left column.

• The student writes the letter of the correct term next to each matching definition.

• The student receives 1 point for each correct response.

• Each probe lasts 5 minutes.

• 2-3 probes are given in a session.

Source: Howell, K. W. (2008). Best practices in curriculum-based evaluation and advanced reading. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes

(Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V (pp. 397-418).

www.interventioncentral.org

82

Response to Intervention

Curriculum-Based Evaluation: Math Vocabulary

Format Option 2

• 20 randomly arranged vocabulary definitions appear in the right column. Items are drawn randomly from a

‘vocabulary pool’

• The student writes the name of the correct term next to each matching definition.

• The student is given 0.5 point for each correct term and another 0.5 point if the term is spelled correctly.

• Each probe lasts 5 minutes.

• 2-3 probes are given in a session.

Source: Howell, K. W. (2008). Best practices in curriculum-based evaluation and advanced reading. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes

(Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V (pp. 397-418).

www.interventioncentral.org

83

Response to Intervention

How Does a Secondary School Determine a

Student’s Math Competencies?

“Tests [to assess secondary students’ math knowledge] should be used or if necessary developed that measure students’ procedural fluency as well as their conceptual understanding. Items should range in difficulty from simple applications of the algorithm to more complex. A variety of problem types can be used across assessments to tap students’ conceptual knowledge.” p. 469

Source: Ketterlin-Geller, L. R., Baker, S. K., & Chard, D. J. (2008). Best practices in mathematics instruction and assessment in secondary settings. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V (pp.465-475).

www.interventioncentral.org

84

Response to Intervention

Identifying and Measuring Complex Academic

Problems at the Middle and High School Level:

Discrete Categorization

• Students at the secondary level can present with a range of concerns that interfere with academic success.

• One frequent challenge for these students is the need to reduce complex global academic goals into discrete sub-skills that can be individually measured and tracked over time.

www.interventioncentral.org

85

Response to Intervention

Discrete Categorization: A Strategy for Assessing

Complex, Multi-Step Student Academic Tasks

Definition of Discrete Categorization: ‘Listing a number of behaviors and checking off whether they were performed.’

(Kazdin, 1989, p. 59).

• Approach allows educators to define a larger ‘behavioral’ goal for a student and to break that goal down into sub-tasks. (Each subtask should be defined in such a way that it can be scored as

‘successfully accomplished’ or ‘not accomplished’.)

• The constituent behaviors that make up the larger behavioral goal need not be directly related to each other. For example,

‘completed homework’ may include as sub-tasks ‘wrote down homework assignment correctly’ and ‘created a work plan before starting homework’

Source: Kazdin, A. E. (1989). Behavior modification in applied settings (4 th ed.). Pacific Gove, CA: Brooks/Cole..

www.interventioncentral.org

86

Response to Intervention

Discrete Categorization Example: Math Study Skills

General Academic Goal: Improve Tina’s Math Study Skills

Tina was struggling in her mathematics course because of poor study skills. The RTI Team and math teacher analyzed Tina’s math study skills and decided that, to study effectively, she needed to:

Check her math notes daily for completeness.

Review her math notes daily.

Start her math homework in a structured school setting.

Use a highlighter and ‘margin notes’ to mark questions or areas of confusion in her notes or on the daily assignment.

Spend sufficient ‘seat time’ at home each day completing homework.

Regularly ask math questions of her teacher.

www.interventioncentral.org

87

Response to Intervention

Discrete Categorization Example: Math Study Skills

General Academic Goal: Improve Tina’s Math Study Skills

The RTI Team—with student and math teacher input—created the following intervention plan. The student Tina will:

Obtain a copy of class notes from the teacher at the end of each class.

Check her daily math notes for completeness against a set of teacher notes in 5 th period study hall.

Review her math notes in 5 th period study hall.

Start her math homework in 5 th period study hall.

Use a highlighter and ‘margin notes’ to mark questions or areas of confusion in her notes or on the daily assignment.

Enter into her ‘homework log’ the amount of time spent that evening doing homework and noted any questions or areas of confusion.

Stop by the math teacher’s classroom during help periods (T & Th only) to ask highlighted questions (or to verify that Tina understood that week’s instructional content) and to review the homework log.

www.interventioncentral.org

88

Response to Intervention

Discrete Categorization Example: Math Study Skills

Academic Goal: Improve Tina’s Math Study Skills

General measures of the success of this intervention include (1) rate of homework completion and (2) quiz & test grades.

To measure treatment fidelity (Tina’s follow-through with sub-tasks of the checklist), the following strategies are used :

Approached the teacher for copy of class notes. Teacher observation.

Checked her daily math notes for completeness; reviewed math notes, started math homework in 5 th period study hall. Student work products; random spot check by study hall supervisor.

Used a highlighter and ‘margin notes’ to mark questions or areas of confusion in her notes or on the daily assignment. Review of notes by teacher during T/Th drop-in period.

Entered into her ‘homework log’ the amount of time spent that evening doing homework and noted any questions or areas of confusion. Log reviewed by teacher during T/Th drop-in period.

Stopped by the math teacher’s classroom during help periods (T & Th only) to ask highlighted questions (or to verify that Tina understood that week’s instructional content). Teacher observation; student sign-in.

www.interventioncentral.org

89

Response to Intervention

Formative Assessment: Essential Questions…

5. How does the school check up on progress toward the goal(s)?

The school periodically checks the formative assessment data to determine whether the goal is being attained. Examples of this progress evaluation process include the following:

– System-Wide: A school-wide team meets on a monthly basis to review the frequency and type of office disciplinary referrals to judge whether those referrals have dropped below the acceptable threshold for student behavior.

– Group Level: Teachers at a grade level assembles every six weeks to review

CBM math computation data on students receiving small-group Tier 2 instruction to determine whether students are ready to exit (Burns & Gibbons, 2008).

– Individual Level: A building problem-solving team gathers every eight weeks to review CBM data to a student’s response to an intensive reading fluency plan.

Sources: Burns, M. K., & Gibbons, K. A. (2008). Implementing response-to-intervention in elementary and secondary schools:

Procedures to assure scientific-based practices. New York: Routledge.

Shinn, M. R. (1989). Curriculum-based measurement: Assessing special children. New York: Guilford.

www.interventioncentral.org

90