Heidi Ross-CIE Doctoral Programs - EU

advertisement

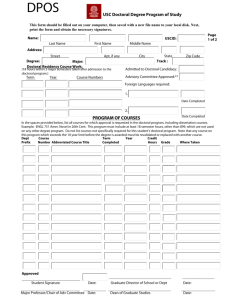

Globality, Bifocality, and In/ternationality in CIE Doctoral Programs: Rethinking the Training and Experiences of Transnational Doctoral Students Heidi Ross, Indiana University Yimin Wang, University of Illinois with Yue Ren, Communications University of China 2014 November 15 Shanghai Jiaotong University 1 CIE Doctoral Training for What and for Whom? The globalization of doctoral education is not just a process but also a condition, “part of a world research environment in which traditional and familiar boundaries are being surmounted or made irrelevant.” (Powell and Green, 2007, 239) [We call this globality] MOTIVATING IMPULSE: the internationalization of doctoral training has been little studied 2 Outline of Presentation • Background, 2010-2014 (as illustrated in handout) • Three Concepts: globality, bifocality, in/ternationality • Literature Reviews along the Way • Findings from Student Surveys 3 Background 21st century research universities have three “faces:” 1. 2. 3. economic markets exchanging products and commodities status-seeking institutions competing for global rankings increasingly networked and collaborating partners (Marginson, 2011). These faces shape the expectations, training and career opportunities of all doctoral students, yet little scholarship on the doctorate examines the needs and impact of trans/international students in/on doctoral programs. With the handout you have as illustration of our questions, I report on the 2010-2014 experiences and training of 14 Chinese doctoral students in a U.S. comparative and international education (CIE) program in terms of its influence on their professional development, affiliations, and employment within an internationalized job market. 4 Three Key Concepts • No shortage of research on what higher education institutions need to do to become “global universities” (Wildavsky, 2010; Altbach and Salmi; 2011) • We agree that “the globalization of higher education should be embraced, not feared,” because globalization is a condition [globality]for the university’s third face of collaboration and partnership. • Bifocality, a concept first used by Ted Bestor, refers to the idea that to understand globalization individuals need to develop experience nearand experience-distant reality. • We borrow in/ternational from Elaine Unterhalter, who describes an important shift in “global space” as moving from two waves: the international, “associated with the primacy of states in “global space,” and the second wave, in/ternational that is “associated with networks, sometimes of states, civil society, corporations, sometimes combinations of these” (Unterhalter, 2008). • Our findings convince us that we should be educating students as global scholars who can reflect on and collaborate in an in/ternational global space. 5 Three Conclusions about Doctoral Training—what it could and should be • Doctoral training is a social practice, from which arises communities of practice that include a shared “intellectual substance” (Wenger, 1998; Cummings, 1999). • Doctoral training programs can foster an appreciation of diversity that flows from bifocality (local to global vision). • Doctoral mentoring can lead to the creation of horizontal, in/ternational connections across national boundaries with the potential for creating global scholars supported by “circles of esteem” (Cribb, 2005). 6 Literature Review, Part 1: Reflections on Comparative Education in China and the U.S. • A review of authors represented in the U.S.-based journal Comparative Education Review (University of Chicago Press) and participants in the annual CIES meetings provide encouraging evidence of the existence of an increasingly robust space for CIE collaboration. • An example: a search of current CIES members with a postal address in China indicates that onethird are Western scholars currently residing in China studying, teaching or doing research; a member search of all states in the U.S. yields at least several Chinese names. Pictures on the CIES main website. http://www.cies.us Literature Review, Part 1: Reflections on Comparative Education in China and the U.S. • The China-based CER (Bijiao Jiaoyu Yanjiu): from describing “trends in foreign education” to actively participating in international dialogue about CIE and its purpose. (196519922010the future) • The implied tension between learning/ adopting/globalizing and serving the social/educational needs of China has been an ongoing one within the Chinese field of CIE and is affected by global interaction. • Chinese CIE scholars have been very consciously reflecting on China’s role in the development of the field(s) of CIE, as well as on what China and Chinabased scholars can contribute to it/them. • WCCES in Beijing in 2016 Literature Review, Part 2: Global Doctoral Training in the U.S. and Worldwide • From the “Carnegie Initiative on the Doctorate,” initiated in 2002 to the “Assessment of Research Doctorate Programs” being conducted by the National Research Council (NRC): the existing literature does little to illuminate our central concern, the nature and role of research for international students—or for all students in a transnational community. • Most of the research that has been conducted focuses on cultivating in undergraduate programs, particularly through general education courses and study abroad programs, global knowledge, understanding, awareness, and citizenship (Nussbaum, 2004; Noddings, 2005; Hanvey, 1982). • Perhaps the “transnational competence” (Hawkings and Cummings, 2000) of doctoral students is taken for granted. But it shouldn’t be! 9 • • • • • CIE and the Larger Debates about Doctoral Training in US Chronicle of Higher Education: blogs: The Professor is In, etc CIES and other professional organizations—New Scholars Committee Market and Training Gaps—recognized everywhere Adjunctification Recognition and research for doctoral students as teachers— “FSSE-G” see http://fsse.iub.edu/ Faculty perceptions of how often students engage in different activities. The importance faculty place on various areas of learning and development. The nature and frequency of faculty-student interactions. How faculty members organize their time, both in and out of the classroom. • MLA report 2014--Report of the MLA Task Force on Doctoral Study in Modern Language and Literature 10 11 Main Points in Report • Pursue and maintain academic excellence. High intellectual standards can be sustained through creative flexibility (of the curriculum, the dissertation, and career preparation). Adaptable doctoral programs can deliver the desired depth, expertise, scope, and credentials. • Preserve accessibility. We need a more capacious view of the humanities’ benefit to individuals and society. Reducing graduate program size denies access to qualified students who want to study the humanities and who will make contributions to academic and public life in their work. • Broaden career paths. Departments must recognize the validity of the diverse careers that students might follow within and beyond the campus and ensure that appropriate orienting and mentoring takes place. • Focus on graduate students’ needs. The profession would do well to endorse a shift from a narrative of replication, in which students imitate their mentors, to one of transformation, since graduate programs should be centered on students’ diverse learning and career development needs. 12 MLA Recommendations • Redesign the doctoral program: to align with the learning needs and career goals of students and to bring degree requirements in line with evolving character of our fields. Noncourse-based activities are essential. • Engage more deeply with technology: provide ways for students to develop and use new tools and techniques • Reimagine the dissertation: both form and committee composition • Reduce time to degree: five years • Strengthen teaching preparation: course work, practical experience, and mentoring for a host of different kinds of institutions—including community colleges • Expand professionalization opportunities: collaboration, project management, grant writing, internships and work with professional associations • Use the whole university community to mentor: librarians, informational technology staff members, administrators. • Redefine the roles of faculty advisers: who must marshal expertise in nonteaching careers, alumni networks, and career development resources. • Validate diverse career outcomes: give students a full understanding of the range of potential career outcomes and support students’ choices. • Rethink admissions practices: calibrate admissions broadened range of career opportunities, taking care to build the pipeline of applicants for small fields and subfields and from underrepresented groups. 13 YET, What’s Missing….Again One mention of international in the entire report: “Preparation for teaching includes teaching diverse populations, both domestic and international. Departments should develop a culture of support of doctoral student teaching, creating peer and faculty mentoring programs and recognizing excellence in the classroom through teaching awards.” 14 ANALYSIS PART 1: Features of American CIE Programs—themes from a dialogue with students • Curriculum design: An emphasis on methodology and personal standpoint • Intellectual Orientation: toward diverse views, practice, and a global? Community • Reference Group • Expectations for the Program 15 ANALYSIS PART 2: Features of Chinese CIE Programs: themes from a dialogue with students • • • • • Curriculum design Intellectual Orientation Building Bridges between two Communities Community Identification Community Identification and Research Interest • Community Identification and Job Opportunity 16 Conclusion: Doctoral Mentoring as Social Practice: Towards Creating a Global Community of Practice • Perspectives and ways of understanding and being understood: One particularly “loud” theme is the extent to which international students become familiar with dominant U.S. discourse, in its many guises, of critically evaluating, appreciating, and coping with difference, diversity, conflict, including that which must sometimes be overcome or embraced to understand another’s point of view. • An example: “what I gained was more like ‘perspectives’– how I understand others and how I am understood by others.” 17 Conclusion: Doctoral Mentoring as Social Practice: Towards Creating a Global Community of Practice • Tension—or perhaps productive friction (Tsing, 2004) in the way Chinese doctoral students understand their gradual adoption of a scholarly identity: Reference groups, fluid yet individualized commitment and willing choice, etc. • An implicit theme of intellectual resistance to dichotomizing here/there, us/them, American/Chinese. • Bifocality—that sense of having a fluid identity with dual vision—is apparently instilled and/or desired: “I want to work in the American research community, but ultimately I hope to promote the development of the Chinese research community.” 18 Conclusion: Doctoral Mentoring as Social Practice: Towards Creating a Global Community of Practice • Diverse reactions regarding their own academic and professional identifications. -- Some are more definite that their reference group is North American. -- “Intellectually, I don't really have a strong sense of distinction between Chinese community and American community.” -- “a little bit of everything (American, Chinese and Diaspora)” -- “Our research is distinct from the traditional Chinese educational scholars…We also differ from the North American research community as the Chinese Diaspora community has our own priorities in terms of topics.” 19 Conclusion: Doctoral Mentoring as Social Practice: Towards Creating a Global Community of Practice • One most significant area of agreement is that the environment necessary to, as one student puts it, be “adaptable in an internationalizing intellectual community” can and should be strengthened. • One of the students most optimistic about creating the third space or community of practice this paper advocates believes that he is being trained to be an active participant in “a global research community as our career tracks know no specific national boundaries.”…“I do believe that the potential to engage all these communities is our asset and we should cultivate such great possibilities.” 20 Conclusion: Doctoral Mentoring as Social Practice: Towards Creating a Global Community of Practice -- So, where does this take us as we strive to provide all of our students, and in the case of this paper particularly international students, what they need to thrive as global professionals and public scholars? • There is near unanimous agreement among Chinese students being trained in one North America university that they learn sophisticated analytical methods. • The near/far perspective: “The fundamental requirement for the researchers who have the ambition of gap-bridging is the training to understand and master qualitative and/or quantitative methodology. Second, they need to have sufficient content knowledge of the political, cultural and educational context in both countries.” 21 Reflections and Future Steps • Future Research – Longitudinal research starting from the time before the students enter the doctoral program • Structural Aspects – Funding – Job Market – How Schools/Colleges of Education define their missions/functions: schooling vs. education – How education fits into the interdisciplinary fields such as international studies, global studies, area studies? – What else? 22