A short introduction to the Literary Culture of the High Middle Ages

advertisement

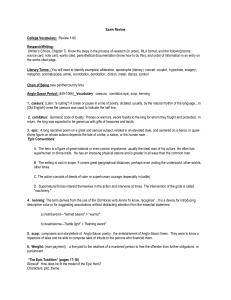

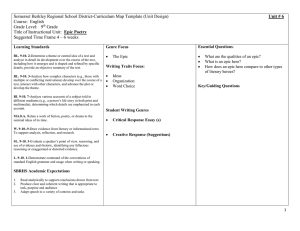

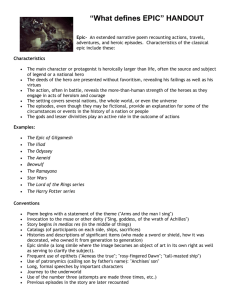

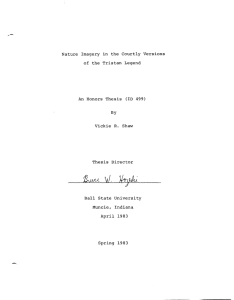

A Short Introduction to the German Literary Culture of the High Middle Ages Traditionally known among literary scholars as --the Blütezeit, or “period of flourishing.” --or, the Stauferzeit – the reign of the Hohenstaufen emperors: Frederick I (“Barbarossa”), Henrich VI, Frederick II -- “Court Literature” (literature produced at the courts of powerful nobles, who were the patrons of the poets) The Historical Context --The “Twelfth Century Renaissance” (Charles Haskins) --The beginning assimilation of new philosophical and scientific texts (early Scholasticism) --The Crusades --Gothic architecture and art The rise of “literatures” in the vernacular languages -- Strong influences from French literature, which developed earlier. -- “Literatures”– the relationship between “orality” and “literacy” is dynamic. -- The “Aufführungssituation,” or “situation of performance.” Literature was originally a performative art. -- The importance of the ministeriales in literary culture. The significant genres Lyric Poetry -- Love Songs -- political / didactic poetry Epic Poetry -- Heroic Epics -- “romanz” (Romance) Drama – None to speak of in the “strict” sense. Cultural Developments during the Blütezeit: --The literature of the Blütezeit demonstrates a welling up of religious / spiritual experience among lay people (in this case necessarily the lay nobility). -- The convergence of this religiosity / spirituality with the values and interests of the lay nobility gives rise to a variety of interesting literary themes and structures. -- The court literature of the High Middle Ages – particularly the romances – endeavor to accommodate sometimes conflicting values and interests . . . . . . and achieve this by virtue of an increased “indeterminacy” or open-endedness. What is the right way to live? Walther von der Vogelweide I sat on a stone and crossed my legs and put my hand against my chin and thought anxiously about the right way to live in this world. I could not figure out how to bring three things together in such a way that one would not ruin the other two. Two of these things are honor and possessions – the interest in one of these often damages the interest in the other. And the third is the grace of God, which is the crown of the other two. Romance as a new Narrative Art Form • The “matter of Rome” and the “matter of Britain.” • Romance: a verse narrative about love and adventure (the definition expands to include prose vernacular narratives that began to be produced in the 13th century). • Note that love and adventure are inherently worldly, “secular” concerns. From M. Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination, Chapter: “Epic and Novel” • On epic poetry: “The epic world achieves a radical degree of completeness not only in its content but in its meaning and values as well. The epic world is constructed in the zone of an absolute distanced image, beyond the sphere of possible contact with the developing, incomplete and therefore rethinking and re-evaluating present.” Bakhtin on the “Novel” (and by implication, Romance, as its older relative) • Basic idea: the novel engages the present in all of its “open-endedness.” • On the “novelization” of other genres ( a long quote– just remember the last idea!): “What are the salient features of this novelization of other genres suggested by us? They become more free and flexible … they become permeated with laughter, irony, humor, elements of self-parody and finally – this is the most important thing – the novel inserts into these other genres an indeterminacy, a certain semantic open-endedness, a living contact with unfinished, still evolving contemporary reality (the openended present).” --For our time-period, substitute “romancing”for “novelization.” Gottfried von Strassburg’s Tristan • • • • • • Gottfried was among the more educated of the medieval authors and presumably lived in Strasbourg – hence, in “urban” surroundings. His Tristan was composed ca. 1210 and based on the Tristan of an AngloNorman poet named Thomas. The Tristan narrative material was part of the “Matter of Britain” (sometimes found in the orbit of King Arthur) Other, earlier versions of the Tristan story were produced by Béroul (in French) and Eilhart von Oberge (in German) – Gottfried says they didn’t get the story right! The versions of Thomas and Gottfried are the poetically and rhetorically most accomplished ones. Gottfried’s poem, in particular, is known for its rhetorically polished and adorned verses, and for its challenging aesthetic conception: --the conception in a nutshell, the adulterous love of Tristan and Isolde is an “Absolute” --Worth repeating: the conception in a nutshell, the adulterous love of Tristan and Isolde is “Absolute” From the Prologue of Gottfried’s Tristan: -- Referring to the story of Tristan and Isolde: “This is bread to all noble hearts. With this their death lives on. We read their life, we read their death, and to us it is as sweet as bread. Their life, their death are our bread. Thus lives their life, thus lives their death. Thus they live still, and yet are dead, and their death is the bread of the living.” The Nibelungenlied • The Nibelungen material has its origins in the migration period (5th and 6th centuries) • In contrast to the courtly narratives, it is basically “Germanic” and “epic” (remember Bakhtin’s conception of epic poetry). • The Nibelungenlied is one of numerous versions of the story of Siegfried and the Burgundian Kings, who die in the end in a battle at the court of Etzel (Attila the Hun). • The Nibelungenlied was composed ca. 1210 by an anonymous poet (anonymity being typical in the authorship of epic poetry) • though considered “epic poetry,” the Nibelungenlied has been largely shaped by the contemporary romances. Romancing Epic Poetry: The Nibelungenlied The character Siegfried shows an interesting double-nature that demonstrates the influence of the romances, with their concerns of love and adventure, on the hero: --He is a fighter of mythic proportions, who has slain a dragon, and bested whole armies single-handedly – the corresponding epic terms: degen, recke. -- He also participates in courtly festivals, tournaments, and falls in love with the beautiful Kriemhilde: the love causes him sometimes to become weak-kneed and turn red as a beet. Besides being a degen, he is also a rîter! In the end the logic of the heroic epic asserts itself. Ther is no courtly happy ending. Conclusion • A reiteration of a position, or argument, that I made earlier: -- Romance (stories of love and adventure) introduce an “indeterminacy” into medieval narrative art. -- narratives thus get closer to being able to express “reality” as something that is open-ended and indeterminate (i.e. subject to chance, contingency, local influences, etc.)