Naturalistic Observation Project: Child Behavior Study

advertisement

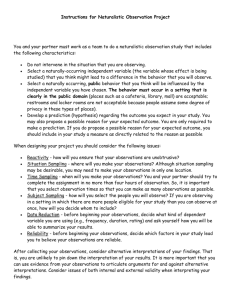

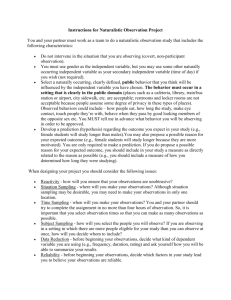

NATURALISTIC OBSERVATION PROJECT (Adapted from the child observation project written by S. Thompson, http://cas.utpb.edu/media/files/Child%20Observation%20Project%202004.doc) I. Purpose of Project It is very easy to be around children without noticing fascinating aspects of their behavior. Indeed, it is rare when anyone intently observes a child for a continuous period, looking for behaviors that characterize an individual child or childhood. Many hours of study and practice are required before a person would become an “expert” observer. II. Initial Preparation A. Select a partner. You will design the project together, but you will write up your report separately. B. Select a situation that will allow you to perform at least 2 sessions of observation in a naturalistic setting. Possible settings could be the cafeteria, the classroom, or the playground. Your observation times will need to be coordinated with the elementary school. Remember, in a naturalistic observation, you do not need to obtain informed consent. However, since this is a school setting, you will need to obtain the consent of the class teacher in elementary school if you wish to conduct your observations in a classroom. We will also seek the permission of the Elementary School Principal to carry out this project. C. The design of your project will be based on Activity 17 on page 67 of your Research Methods text. This means you must complete tasks 1 – 4 in the activity as part of your preparation. Task 5 is your actual project. First review your answers to the questions on page 66 of your text Research Methods. Re-read page 67, paying particular attention to the explanations of observational systems and Sampling Procedures. D. Now read and note down key points in Reading #1 - Group Dynamics (attached to this packet) and on page 68 of Research Methods E. Discuss with your partner the possible answers to questions 2 and 3 on page 68, and note them down. The answers are on the next page. Are you on the right track? If so, move to the next step. F. Creating your initial design Discuss your research aims with your partner (see question 1, Activity 17, page 67 of Research Methods). You might like to actually take a walk to the cafeteria or another public place, on a ‘scouting’ mission as part of your discussion. You may only do this initial observation in public areas. Please have your research aims ready by the next lesson. In the next lesson, we will be ready to put the final touches to your design, and organize permission. Answers to Qs 34 1. Participant observation, naturalistic observation. 2. In each case the answer could arguably be event or time sampling, but some example answers are given below a. Time sampling, every 10 seconds record behaviour of a target child. b. Event sampling, note down each time a child makes a particular sound or sounds. c. Event sampling, every time someone crossing note the details. d. Event sampling, note every time someone drops litter and the details e.g. age, gender, what was dropped. e. Follow a dog owner and use time sampling, every 30 seconds write down what they are doing. 3. a. e.g. Students spend more time staring into space than reading their books. Students spend a significant amount of time talking to friends. b. e.g. reading book, staring into space, talking to friends, making notes, looking for a book, getting ready to work c. Event sampling. I would observe one student and tick each time they did one of the behaviours in the checklist and for how long. Time sampling. Every 15 seconds note what the target student is doing. d. e.g. Pretend to be another student working in the library (participant observation). One way mirror is unlikely. e. e.g Invasion of privacy, lack of informed consent. f. Privacy: dealt with through justification that a library is a public place therefore not invading privacy. It is acceptable though people may still feel you shouldn’t observe them when they don’t realize they are being observed. Informed consent: obtain informed consent afterwards and offer right to withhold data. This seems acceptable though may make people feel wary in the future. g. You are watching people going about their everyday business and not interfering in any way. h. It’s a method 4. a. e.g. (1) Test results for each group of students (2) Attention paid to teacher in class b. Tell students the observer is a student teacher observing the teacher’s behaviour (might still be a bit obtrusive), one way mirror, use test results because then don’t actually observe the teacher’s behaviour. c. If you are watching the teacher then you could use time sampling to check on attentiveness of students. d. e.g. Advantage: Observe real-world behaviour, teaching style in a natural context. Disadvantage: May be hard to do it without students/teachers being aware of being studied which would affect the external validity of the findings. e. e.g. (1) informed consent (2) confidentiality (of ratings given to teacher) f. It’s a technique. Reading #1 Group Dynamics Source: VCU College of Humanities and Sciences http://www.has.vcu.edu/group/case.htm One of the best ways to understand groups, in general, is to understand one group, in depth. The case-study approach has a long and venerable tradition in all the sciences, with some of the greatest advances in thinking coming from case studies rather than from experiments or survey studies. The field of group dynamics, in particular, is checkered with case studies that have transformed the field: the case analyses conducted at the Hawthorne Plant of the Western Electric Company (Landsberger, 1958; Mayo, 1945; Roethlisberger & Dickson, 1939); Janis's studies of groups suffering from groupthink; William Foote Whyte's brilliant Street Corner Society; Newcomb's Bennington study are all major contributions to the field. Case studies' disadvantages are, of course, often noted: the group studied may be unique, and the observer (most case studies involve observation) may be biased in his or her perceptions. Hypotheses can rarely be put to an objective test, and in some cases the analysis may not rise above mere description. But they have strengths as well. They are simple, direct, and to-the-point: By examining a group during its actual activities, you gain understanding of such groups in general. They are higher, in some cases, in external validity, and they can also be the crucible for more advanced theoretical analysis. Indeed, extending David B. Miller's comments about naturalistic observation to case studies of groups (1977, American Psychologist, Vol. 32, pp. 211-220), we find that case studies are useful because they allow us to study groups, for their own sake serve as a "starting point for investigating certain behavioral phenomena and subsequently serve as a point of departure from which to develop a program of laboratory research" (Miller, p. 213); can serve to validate findings obtained in laboratory settings; provide us with a larger context for understanding groups as they form, develop, and disband in their natural settings; can, in some cases, provide the researcher with the opportunity to use his or her more traditional research tools, but in a naturally occuring situation. There is no one correct way to carry out a case study, but the following suggestions are offered to maximize the method's strengths and minimize its weaknesses. 1. Identify a group for study. Groups are everywhere, and many of them are open to the public. You can also carry out a participant observation study, as well, although your analysis will more than likely be influenced by your unique position in the group. Most groups would be willing to let you attend their meetings if you explain you are a student of groups, and want to watch what goes on. Get consent, and don't put you or the group you study at risk in any way. 2. Become familiar with the group by studying its artifacts, products, and location. Try to gather, from resource materials or printed matter, a list of all members and their positions. Examine the physical location the group occupies, and try to determine where the group members live and work in relation to one another. You should know the group members' names (or, at least, have developed labels for the members if they are anonymous) and their positions before you try to describe a group's interaction. Be able to describe them as individuals. 3. Watch the group in action. Groups are, well, dynamic. It is difficult to watch a group interact and record all the relevant information. But you should note where individuals sit in relation to one another, who talks to and after whom, who talks the most and who talks the least, and you should try to categorize (in general terms) the content of the communication: e.g., who is making task- focused comments, who concentrates on socio-emotional activities. You should try to be sensitive to nonverbal messages, and always, always, take notes. Expand the notes immediately after the observation. 4. Develop a conceptualization of your group. All good case studies go beyond describing the group--they also offer theoretical insights into groups, in general, by drawing out the theoretically interesting aspects of the group observed. Theories of group development, of structure, of status acquisition, of performance, abound, and can be applied to the group you are watching. 5. Generate a case study, which should take the form of a brief scientific paper. It is often appropriate to include an introduction, method, results, and discussion section. 6. If possible, supplement your observational information with quantitative information about the group. If you are interested in the group's structure, ask members to complete the SYMLOG. If you are interested in who interacts and who does not, then administer a shyness measure and examine the results. Do not, of course, let your desire for quantitative indices undermine your relationship with the group, or use measures that might be ethically questionable.