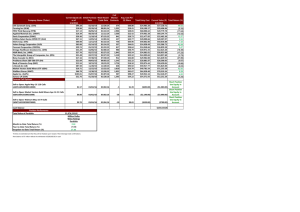

Option 1: Support the ETF II pooled fund

advertisement