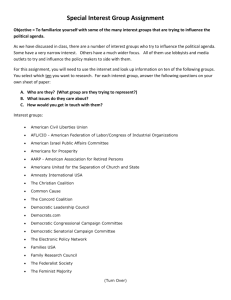

From Hoover to Obama, the 1928 Thread

advertisement

The 1928 Thread in American Politics: The Culture War of the Twenties and its Legacy Herbert Hoover, 1928 Republican Nominee For President: Beneficiary of the 1920s Culture Wars Warren G. Harding (Republican) Years in office: 1921-1923 Calvin Coolidge (Republican) Years in office: 1923-1929 Al Smith, 1928 Democratic Nominee for President Al Smith (1873-1944) was a Democrat who served as Governor of New York during the 1920s, and was a known Progressive. He was a so-called Wet Democrat in that he opposed Prohibition. He was also a Roman Catholic in an era of widespread Anti-Catholicism. In 1928, Smith was popular among Catholics, immigrants, and many urban voters. Smith was unpopular with many rural voters, and Protestants such as Southern Baptists and Lutherans. Culture War and the 1928 Election: The Otherness of Democrat Al Smith A Catholic and an opponent of Prohibition, Al Smith was effectively demonized by his Republican opponents as being un-American and disloyal, campaign tactics that Republican would use effectively against Democrats in coming decades. In 1928,for example, it was rumored that, were Al Smith to win, the Pope would end up ruling the United States. The Pro-Ku Klux Klan publication at right pictures Al Smith as a candidate completely controlled by the Catholic Pope. . 1928: Herbert Hoover and the Slow Rise of the Republican Party in the South In a sense, the presidential election of 1928 began a slow process of party realignment in the South. From 1928 on, the Republican Party slowly became an increasingly conservative party with increasing appeal in the conservative South. Conversely, the Democratic Party evolved in a more liberal direction, and by the mid-1960s, the once solid Democratic South was a concept that was all but dead. Background to 1928: The Democratic Solid South in 1924 In 1924, the Democrats (shown below in blue) carried all eleven of the former Confederate states. The Political Importance of the South, the Nation’s most Conservative Region Since the American Civil War, the South has typically been the most conservative region of the country, particularly in matters of religion, traditional values, and resistance to social change. From the end of Reconstruction in the late 1870s to the mid-1960s, white Southern voters and politicians were generally among the most conservative in the nation. As such, because the South remained predominantly Democratic until the 1960s, the Democratic Party therefore had a conservative wing with much of its membership being Southern. But from 1928 on, the white South found itself increasingly at odds with the increasing liberalism of the Democratic Party at the national level. This, in turn, created the possibility of mass defections of white southern voters away from the Democrats and into the Republican Party. Such a regional voter re-alignment, however, would likely influence the Republican Party towards becoming a much more conservative party. Let us now turn to see if that happened. 1928: Al Smith defeated by the Three P’s: Prohibition, Prejudice, and Prosperity Pictured below is a KKK Flyer denouncing the Catholic Democrat, Al Smith Reporter Frederick William Wile famously quipped that Democrat Al Smith was defeated by the “three P’s of Prohibition, Prejudice, and Prosperity.” In many respects, the 1928 election was a signature event in that the winning Republican candidate benefitted from the American culture war, and moreover, allowed the Republican Party to make significant inroads into the South for the first time since Reconstruction. Twenty years later, American culture wars would re-ignite with the ultimate long-term effects of making the Republican Party dominant in the South. Background to 1928 The Culture Wars of the Twenties: The Prohibition of Demon Rum In 1919, with the passage of the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act, Alcoholic beverages became illegal throughout the United States. Prohibition enjoyed widespread support among Protest Evangelical Christians who, for the most part, were opposed to Roman Catholicism both religiously and culturally. Background to 1928 The Culture Wars of the Twenties: Anti-Immigration In the wake of WWI, American public opinion turned against immigration. In 1924, Calvin Coolidge signed the JohnsonReed Act into law, a statute that greatly limited new immigration into the United States. American anti-immigration sentiment overlapped with the anti-alcohol and anti-Catholic sentiment of the 1920s. Background to 1928 The Culture Wars of the 1920s: Anti-Evolution Crusades In addition to a broad-based anti-Catholicism, many traditional Protestants (Evangelicals and Fundamentalists) were deeply opposed to some of the new teachings of modern science, particularly the teachings of Charles Darwin and his Theory of Evolution. In the mid-1920s, the so-called Scopes Monkey Trial in Dayton, Tennessee became a cause celebre in which a public school teacher went on trial for teaching evolution, an action in violation of state law. Secular lawyer Clarence Darrow famously made William Jennings Bryan (a religiously devout Democrat) look foolish during the trial, and Bryan died shortly after. But opposition to evolution survived in much of rural America, particularly the South. Background to 1928 The Culture Wars of the 1920s: The Ku Klux Klan The Ku Klux Klan on parade in Washington, D.C. in 1928 Revived in 1915, the Ku Klux Klansmen served as activists and shock troops on behalf 100% Americanism. The KKK advocated white supremacy, Protestant Christianity, Anti-Catholicism, AntiSemitism, and Prohibition. During the twenties, the KKK possessed national strength and marched on Washington more than once. The Great Depression, the New Deal, and the Two-Party System When the Great Depression hit the U.S. in 1929, President Hoover and the Republican Party took the blame. In the 1930 midterm elections the Republicans lost many seats in Congress. Moreover, conservative Republican economic policies fell into disfavor. Politically, Hoover was a dead man walking by 1932. When the FDR and the Democrats took power in 1933, the U.S. was ready for a New Deal of government economic activism. The Culture War Suspended…sort of, 1929-1945 In 1933, Prohibition was repealed with the ratification of the 21st Amendment. To a certain extent, the Culture War was suspended during the Age of Roosevelt, particularly the cultural issues that animated the 1920s. After the Great Depression and WWII, however, the Culture War returned with great vigor, particularly in the South. FDR and the South: Dixie Returns to the Democratic Fold (1932-1944) In 1932, during the depths of the Great Depression, Franklin D. Roosevelt of New York, the Democratic candidate for president easily defeated Republican Herbert Hoover. 1932 was the biggest party re-alignment election since the Republicans became the majority party in the wake of the 1860 elections. As a result of the 1932 Democratic tidal wave, FDR’s Democratic Party took the reins of the Presidency, Congress, and much of state and local government. FDR was re-elected in 1936, 1940, and 1944. In four straight elections, FDR carried all eleven of the former Confederate states. For the most part, white southern voters either supported or made peace with FDR’s New Deal. Harry Truman and the Rebirth of the Culture Wars On April 12, 1945 President Franklin D. Roosevelt died. In turn, Vice President Harry S. Truman of Missouri became the President of the United States in the waning months of WWII. In 1948, Truman defeated Republican Thomas Dewey, and served four years more. During the Truman years American culture wars re-ignited on two major fronts: Anti-Communism and Civil Rights. In 1950, Republican Senator Joe McCarthy began making accusations that, under Democratic rule, the federal government had become saturated with Pro-Soviet Communists. An underlying theme of McCarthyism was that American liberal Democrats were unfit to hold power. The rise of McCarthyism coincided with growing southern resistance to Civil Rights initiatives. In time, opponents of Civil Rights would voice many of their arguments in the context of anti-communism. The Democratic Party and Civil Rights: The Southern Revolt of the late 1940s In 1948, Democratic President Harry S. Truman (who had assumed the presidency in 1945 after the death of FDR) ended racial segregation, by executive order, in the U.S. military. With this action, President Truman began the slow process of aligning the national Democratic Party with the larger agenda of securing legal and social equality for AfricanAmericans, i.e. civil rights. For many conservative southern Democrats in the South, this was a threat to their traditional way of life. A revolt, in turn began to brew among some southern Democrats. At the 1948 Democratic Convention, northern liberal Democrats succeeded in having a pro-civil rights plank added to the party platform. This sparked a walk-out by certain Southern convention delegates. The Dixiecrat Revolt had started. The 1948 “Dixiecrat” Ticket Did the Republicans Conquer Dixie, or did Dixie Conquer the Republicans? J. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina Thurmond was a Democrat who became a “Dixiecrat” in 1948, and led a Southern Revolt against the Democratic Party. In 1964, after Democratic President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law, Senator Strom Thurmond became a Republican. Thurmond continued to serve as a senior conservative Republican senator until he died in 2003. 1948 and the Dixiecrat Revolt The Dixiecrat revolt of 1948 cracked the Solid South on behalf of white supremacy. McCarthyism, Anti-Communism, and the Liberal-Conservative Culture War In 1950, in Wheeling, West Virginia, a littleknown Republican senator, Joe McCarthy of Wisconsin claimed in a dramatic speech that he possessed a list of names of Communists within the U.S. government. McCarthy continued his anti-Communist crusade via congressional hearings. McCarthy was not the first Republican to use “Red-baiting” political weapon against liberal Democrats. Richard Nixon, in fact, has mastered this art well before McCarthy did. Nor was antiCommunist Red-baiting an exclusively Republican tactic. But Republicans like Congressman Nixon and Senator McCarthy proved particularly skilled at linking communism and liberalism, particularly the liberalism of Democrats. While the anti-Catholicism had been jettisoned (McCarthy himself was Catholic), aspects of McCarthyism harkened back to the antiimmigrant and 100% Americanism movements of the 1920s. In short, the 1928 Thread was quite intact in the period known as McCarthyism. “I Like Ike”: The Age of Eisenhower, 1953-1961 In 1952, the Republican Party won the presidency for the first time in 20 years, the first time since the Herbert Hoover administration. In the 1952 election, former WWII general, Dwight D. Eisenhower defeated Adlai Stevenson of Illinois, and would do so again in 1956. While “Ike” was a moderate Republican in both ideology and temperament, his Vice President, Richard M. Nixon, was a master of the 1928 Style of conservative campaigning, and was a “serial collector of resentments.” In 1968, Nixon would capitalize on white voter anxieties and win the presidency in his own right. But for the most part, the Eisenhower presidency was characterized by prosperity and political moderation, both in campaigning and governing. Moreover, both the Democratic and Republican parties each had liberal and conservative wings in their respective parties. In short, during the 1950s, and for much of the 1960s, the two major parties were not yet neatly aligned on either side of the liberal-conservative cultural divide. For the time being, the center held. But below the surface, among many in the American public, resentment and anxiety was building, particularly among small town whites, and even more particularly among whites in the South. May 17, 1954 Brown v. Board of Education In the spring of 1954, under the leadership of Chief Justice Earl Warren, a liberal Republican, the United States Supreme Court issued a 9 to 0 decision striking down racial segregation in public schools. The Brown decision put the traditional Southern way of life in jeopardy, and recalcitrant white Southerners mobilized for massive resistance to the Supreme Court and the growing Civil Rights Movement. For the time being, segregationists focused their rage against Republican Earl Warren’s Supreme Court. In 1957 Republican President Dwight Eisenhower enforced the integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. For the time being, the Democratic Party did not suffer a massive exodus of white Southern voters. This would begin to change when President John F. Kennedy (1961-1963), a Democrat, slowly moved his administration towards support of a broad-based elimination of Jim Crow racial segregation 1961-1963: John F. Kennedy and Civil Rights Though something of a late-comer to the Civil Rights issue prior to becoming president, JFK and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, threw administration support behind the Civil Rights movement, on behalf the the 1961 Freedom Riders, on the behalf of integrating the University of Mississippi in 1962, and on behalf of integrating the University of Alabama in 1963. Coinciding with the civil rights showdown at the University of Alabama, JFK made a televised address to the nation on June 11, 1963. In this message Kennedy called for the end of Jim Crow racial segregation and the passage of a comprehensive civil rights bill that would end segregation in most areas of life. In doing so, JFK put the national Democratic Party explicitly on the side of ending what many conservative white southerners considered to be the “Southern way of life.” Along with liberal and moderate Republicans, the national Democratic Party had aligned itself inextricably with the Civil Rights movement and a call for significant social change. This continued to set the stage for mass defections of Southern white voters out of the Democratic Party, and into an increasingly conservative Republican Party. Lyndon B. Johnson and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 On November 22, 1963, President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas. In turn, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson became President. A former Majority Leader of the U.S. Senate, LBJ made the passage of JFK’s agenda a high priority. In the summer of 1964, LBJ secured a coalition of liberal and moderate Democrats and Republicans in Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, a law that outlawed, among other things, racial segregation in public accommodations. LBJ signed the bill into law on July 4, 1964. LBJ reported quipped that the Democratic Party had now “lost the South for a generation.” History would prove that LBJ was largely correct. 1964: In a landslide loss, conservative Republican Barry Goldwater won five Deep South states The Civil Rights Act of 1964 did much to remove white Southern voters from the Democratic camp. In the Presidential election of 1964, Republican Senator Barry Goldwater, an opponent of the civil rights bill, lost 44 states. But he won 5 states in the Deep South (Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Georgia, and South Carolina). In short, as the Republican Party became more conservative, the South became more Republican. Segregationist Alabama Governor George C. Wallace In 1962 George C. Wallace of Alabama ran for governor on a staunch platform of racial segregation. In 1963, he “stood in the schoolhouse door” at the University of Alabama in defense of racial segregation. In 1964, Wallace made a minor run for president as a Democrat, but as an opponent to the liberal wing of the Democratic Party In 1968, however, Wallace ran for President as an independent and carried five southern states. Nixon carried five other southern states. In short, Wallace did much break away white southern voters from the Democratic Party. Nelson Rockefeller, George Romney, and the Decline of the Liberal Republicans During the 1950s and 1960s there still existed a moderate/liberal wing of the Republican Party. In fact, without the support of moderate and liberal Republicans (and the leadership of Republican senator, Everett Dirksen of Illinois, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 would not have passed the Senate, and would not have become law. During that period two prominent Republicans embodied the liberal wing of the Republican Party, those being Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York and Governor George Romney of Michigan. In 2012, George Romney’s son, Mitt, became the presumptive Republican nominee for president. By the early 21st century, Republicans like Rockefeller and George Romney, however, were largely extinct In 2012, Mitt Romney was a new breed. Richard Nixon and the Southern Strategy In 1968, Richard Nixon campaigned on a platform of “law and order,” a message tailored, in part, to disaffected Southern whites. The strategy paid off in both 1968 and 1972, and Nixon enjoyed great popularity in Dixie until nearly the end of his presidency in 1974. 1973: Roe v. Wade and the Expansion of the Culture War In January 1973, coinciding with the death of former Democratic president Lyndon B. Johnson, the U.S. Supreme Court declared in Roe v. Wade that early stage abortions are constitutionally protected. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, the abortion issue became one of the dividing line matters in the expanded liberal-conservative culture war. By the early 1980s, the Republican Party platform explicitly called for the overturning of Roe v. Wade while, in turn, the Democratic Party explicitly called for continuation of abortion rights for women. The Catholic Church and many conservative Protestant religious groups sided with the Republicans, and increasingly made their camps there. By 1980, as it did in 1928, the presidential election took on a religious tenor with the rise of the Religious Right. This time, however, it was not Catholic versus Protestant, but instead was more religious conservatives versus secular liberal & religious liberal. The Fall of Richard Nixon and the Caretaker Presidency of Gerald R. Ford In 1968 and 1972, Richard M. Nixon proved quite skilled at exploiting the resentments of white Middle America voters, voters who disliked much of the 1960s counterculture, particularly the Anti-War Movement and the increasingly radical Civil Rights Movement. In 1972, Nixon effectively portrayed his Democratic opponent, George McGovern, as a coddler of social deviance. As in 1928, the Republicans benefitted from the perception that the Democratic presidential nominee was unfit to be president, and was on the wrong side of the culture war. But in 1973-74, the Watergate Scandal (a scandal born in the Nixon effort to fight a culture war) resulted in the death of Nixon’s presidency. In August 1974, Nixon resigned. As such Vice President Gerald R. Ford (who had recently replaced the resigned Spiro Agnew) became president. He served out the remainder of Nixon’s second term. As president, Gerald Ford governed as a moderate, and avoided the cultural cleavages that Nixon exploited so skillfully. 1976: Democratic Jimmy Carter Wins but Fails to Hold the South In the 1974 midterm elections, only 3 months removed from Nixon’s resignation, the Democratic Party picked up congressional seats and were poised for a big presidential win in 1976. As it turned out, the Democrats did win, but by a close margin. The Democratic victor was former governor Jimmy Carter of Georgia. Campaigning largely on a platform of restoring trust, Carter defeated President Gerald Ford in a close election. In doing so, Carter carried 10 Southern states, though this was due in part, to widespread Black voting in the South. Carter’s presidency, however, was plagued with a bad domestic economy at home, and foreign policy stumbles abroad. In 1980, Carter lost 10 of the former Confederate states to Republican Ronald Reagan. The four year interregnum was over. Dixie was back in the Republican fold, and since 1976, no Republican presidential candidate has done poorly in the South. In short, after 1976, the South has remained a conservative electoral anchor for the Republican Party during presidential elections. The Reagan-Bush Era 1981-1993 In 1980, Republican Ronald Reagan won a landslide victory over President Jimmy Carter, and for the first time since the 1950s, the Republicans took over the U.S. Senate, though the Democrats still controlled the House of Representatives. In 1984, Reagan carried 49 states versus Democrat Walter Mondale, and won all eleven former Confederate States. Already a conservative icon, Reagan’s presidency was oriented around a conservative agenda, albeit a nuanced and temperate conservative agenda. FDR’s New Deal, LBJ’s Great Society, and Civil Rights were left intact with only minor adjustments. Outside of tax policy, one could argue that Reagan governed as a moderate conservative who avoided politically risky radicalism. In 1988, Vice President George H.W. Bush effectively portrayed his Democratic opponent, Michael Dukakis of Massachusetts, as an unpatriotic coddler of criminals who was too liberal for the American people. Bush’s campaign strategy was designed by Strom Thurmond protégé, Lee Atwater of South Carolina, and it worked mightily. Bush cruised to victory in 1988 with a campaign style that echoed that of 1928. But unlike Reagan, Bush was never beloved by conservatives, and during his presidency, Bush’s moderation was never overlooked as Reagan’s had been. When Bush broke his promise not to raise taxes, he lost credibility with his conservative base. As the economy tanked in 1991-92, Bush became politically vulnerable. In 1992, he lost to a Democratic southerner, Governor Bill Clinton of Arkansas The Bill Clinton Presidency: January 1993 to January 2001 In 1992, despite personal scandal and an anti-war counter-culture background, Democratic governor Bill Clinton of Arkansas won the Democratic nomination for president and later defeated President George H.W. Bush in the general election. At the 1992 Republican Convention in Houston, conservative activist Pat Buchanan declared, to roaring approval, that the U.S. was in the midst of a culture war for the soul of America. He furthered that George H.W. Bush was on one side of the war, and Bill Clinton was on the other. For the rest of the 1992 campaign, the Republicans continued to play on these culture war themes, though in the end, Clinton and the Democrats prevailed. During Clinton’s two-term presidency, much of America’s political battles were played out in terms of the Culture War. In 1998, Clinton became ensnared in a sexual scandal. The ensuing battle was carried out, at least among the Republicans, as something of a religious crusade. At one juncture, Republican congressman Tom DeLay of Texas painted the issue of Clinton’s scandal as a matter of defending the concept of absolute truth. The Clinton culture wars climaxed with his impeachment by the Republican-dominated House of Representatives in December 1998. The Senate, however, failed to convict, and Clinton remained president and served the rest of his second term. The Rise of Newt: Southern Republicans in the 1990s In 1994, Republican Representative Newt Gingrich of Georgia led a Republican takeover of the House of Representatives, a body controlled by the Democrats since 1955. The Republicans also took over the U.S. Senate, and thus controlled Congress for six years while Bill Clinton was President. In 1995 Gingrich became Speaker of the House. Later, Senator Trent Lott of Mississippi became the Senate Majority Leader, thus ensuring for the Republicans that Congress would be lead by conservative Republican from the South. In 1994, Gingrich and his fellow congressional Republicans ran an effective campaign in labeling the Democrats as being morally unfit to lead the country. In particular, Gingrich and company capitalized on cultural resentments of white voters (particularly white Southern voters), and Gingrich proved particularly skillful as portraying Bill Clinton and the Democrats as being on the wrong side of a larger culture war. Though Gingrich himself was ousted as Speaker in the wake of the 1998 elections, the Republicans maintained control of the House of Representatives for 12 years, until losing the midterm elections of 2006. To this day, much of Republican representation in the House of Representatives is firmly rooted in conservative white-majority districts in the South. The Age of Dubya 2001-2009 Though the presidential elections of 2000 and 2004 were razor-thin, George W. Bush of Texas proved to be a very popular candidate among conservatives, particularly those in the South. In both 2000 and 2004, Bush carried each of the former Confederate States (though 2000 Florida is still disputed). As a candidate, and as president, Bush consistently invoked conservative culture war themes, and proved very effective at portraying his Democratic opponents as being unpatriotic, and even un-American. During the Bush years, the term liberal increasingly became a term of derision. In the wake of the September 11, 2001 Al Qaeda terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington, D.C., Bush wedded his “War on Terrorism” with the American culture war. The strategy paid political gold for the Republicans. The Republicans re-took the Senate in 2002, and Bush won re-election in 2004. But Bush-style conservatism reached its high water mark in 2004. By 2006, the Iraq War had descended into a quagmire, and in 2008, the U.S. economy collapsed. Like Herbert Hoover (the winner in 1928), Bush became a political Dead-Man-Walking in the final months of his presidency. Unlike Hoover in 1932, however, John McCain (the Republican nominee in 2008) had to pay the price of Bush’s political demise. 1928 and 2008 Culture Wars with Different Results In 2008, the Democratic Party nominated Senator Barack Obama of Illinois as its presidential nominee, and Senator Joe Biden of Delaware as Vice President. The Republicans nominated Senator John McCain of Arizona for president and Governor Sarah Palin of Alaska as vice president. In 2008, the Republicans sort of returned to the 1928 election strategy of portraying the Democratic nominee as un-American. This time, eighty years later, the results were different. The Obama-Biden ticket won 29 states and 365 electoral votes, a surplus of 95 more than he needed. The Age of Obama and the Dawn of the Tea Party Elected by a comfortable margin in 2008, Barack Obama became the first African-American president on January 20, 2009. Obama’s victory came roughly 80 years after Al Smith’s 1928 defeat. But within months, conservative Republican backlash intensified into a movement that became known as the Tea Party. An overwhelmingly white conservative movement, this loosely-associated movement possessed a family resemblance to the 100% Americanism movements of the 1920s. Continued Culture War and Barack Obama’s Otherness When Senator Barack Obama became the Democratic presidential nominee in 2008, many conservatives responded that Obama was un-American and subversive. Some even questioned as to whether Obama was really born in America at all. Later, he felt compelled to release his birth certificate to prove his citizenship In many respects, the Obama’s enemies utilized similar tactics as did the opponents of Al Smith in 1928. As of 2012, the culture wars continue, with presidential elections being oriented along the lines drawn in liberalconservative lines. And in that sense, 1928 should be seen as a dividing point in the political history of the two major political parties. The 1928 Thread in U.S. Politics, 1928-Present Since 1928, national American politics, particularly presidential politics, have often become oriented around liberal-conservative culture wars. And in that sense, the presidential election of 1928 launched an important juncture in the history of American presidential campaigns. For the first time, in significant numbers, the Democratic nominee was widely perceived as being the wrong side of a larger culture war, and was seen in such a was as being un-American, disloyal, and subversive---well beyond being merely wrong on the issues. The Republicans reaped the benefits of these perceptions in a landslide 1928 victory, and would do so again in 1968, 1972, 1980, 1984, 1988, 2000, and 2004. In the early 21st century, the 1928 Thread was a recurrent American political theme.