LN Wk 7-1 Douglass's Speech

advertisement

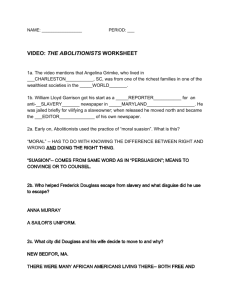

Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” Delivered July 5th, 1852 Corinthian Hall Rochester, New York • Rochester Ladies’ Antislavery Society of Rochester • 500-600 people, 12 1/2 cents each • FD letter to Gerrit Smith: 2-3 weeks of preparation (cf. opening: “no elaborate preparation”; “I have been able to throw my thoughts hastily and imperfectly together”) • Prayer; reading of the Declaration; speech; “universal burst of applause” John W. Blassingame, ed. The Frederick Douglass Papers. Series One. Speeches, Debates, and Interviews. Vol. 2. 1847-54. New Haven: Yale UP, 1982. 359-88. Circulation • Request for publication in pamphlet form • 700 “subscriptions” on the occasion • Published in Frederick Douglass’ Paper (formerly the North Star), 9 July 1852. Issue 29, col. D: “The Celebration at Corinthian Hall” The structure of the speech • Douglass’ headings – – – – – – [Intro] The Internal Slave Trade Internal Slavery Religious Liberty The Church Responsible Religion in England and Religion in America The Constitution • Three parts (Blight): “three essential rhetorical moves” – Setting patriotic Americans at ease – “Bitter critique” – Ending with hope Another way to think about structure: from Cicero, De Oratore (On the Ideal Orator, 1st century B.C.E.) • exordium – introduction; exhorts (calls to) people to attend to the speaker’s presence and themes • narratio – the story or historical context for the issue under discussion • confirmatio – the case being made: what is argued • refutatio – refuting counter arguments: what do people say against the position and how are they wrong • peroration – the “outside” of the oration: the conclusion Ethos, structure, irony • Caleb Bingham’s Columbian Orator (1797): rhetorical instruction focused on delivery, not “disposition” (organization) • Douglass would have learned inductively: by reading examples • Douglass refers to but inverts or treats ironically almost every structural element of the classical oration • [irony: incongruity or discordance between what is expected and the state of things] • This inversion of expectations contributes to the central irony of his situation as speaker: “why am I called upon to speak here to-day? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence?” (155). • Irony rather than argument: “At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument is needed” (158). Exordium (¶ 1-3): • Douglass: I won’t “grace my speech with any high sounding exordium” (148). • Little learning • Modesty trope - a conventions • BUT consider the rhetorical questions: Who speaks? To whom? (slavery, race, class) • Distance: “between this platform and the slave plantation, from which I escaped” (148) Narratio: the story, historical context (¶4-31; 149-56) • Occasion, exigence (situation): what calls forth the rhetorical act? What genre is required? – 4th of July celebration: epideictic (ceremonial, occasional) – Slavery: abolitionist advocacy (deliberative, toward changes in policy) • Time: past, present, and future – The childhood of the Republic of America - hope, consolation: “Were the nation older, the patriot’s heart might be sadder, and the reformer’s brow heavier” (149). MLK, Jr., “I Have Dream” August 1963: “the tranquilizing drug of gradualism” – Geological time: analogy of nation to river – A “simple story” -- well-known: “as a people, Americans are remarkably familiar with all facts which make in their own favor: a national trait, a national weakness” (154) A way of viewing time becomes an argument: the time of ceremony is redefined: from static principles and “simple story” to precarious chain of destiny • Narratio as argument • “Just here . . . Was a startling idea born” (151): the novel, inaugural quality of the Declaration • An uncompleted project: “The 4th of July is the first great fact in your nation’s history--the very ring-bolt in the chain of your yet undeveloped destiny” (152). • “The Declaration of Independence is the Ring-Bolt to the chain of your nation’s destiny . . . Stand by those principles” (152) • “That bolt drawn, that chain broken, and all is lost” (152). The ship of state imperiled: crisis Ethos, time, and the founding fathers • The most obvious feature of Douglass’ ethos is dis-identification with “Americans”: “your National Independence” (149) • My thesis: Despite the many overt moves to differentiate himself from the audience--to create distance--Douglass forges identification with the founding fathers and his abolitionist audience by emphasizing the courageous character of American revolutionaries in the moment. He seeks to persuade the listeners to accept his chronology and take responsibility for realizing in their own moment the uncompleted project launched by the Declaration by acting against slavery. • “To side with the right, against the wrong, with the weak against the strong, and with the oppressed against the oppressor! Here lies the merit” (150). Standpoint - distance reconsidered “The point from which I am compelled to view them . . .” (152) Distance creates authority: D. moves from “living evidence” (supplicant, informant) in the Narrative to instructor on fidelity to the principles of the Declaration: “stand by those principles . . . At whatever cost” (152) And yet, “I will unite with you to honor their memory” (152): an oscillation between division and identification Identification through style • A scene “simple, dignified, and sublime” (152( • “They were peace men . . .”: antithesis • “Their statesmanship looked beyond the passing moment, and stretched away in strength into the distant future” (153). • The national superstructure rising in grandeur around you: “Fully appreciating . . ., firmly believing . . .” (153) Competing visions: the static edifice vs. the storm-tossed ship of state • “ My business is with the present . . . the ever-living now” “Now is the time, the important time” “ You must live and must die, and you must do your work” (¶29, 154). • Washington’s monument built “by the price of human blood,” yet Washington “broke the chains” of his slaves (155). • Enlightenment principles performed rather than asserted Sharp reminders of distance/division Genealogical (154) Legal/civic (155) • “This Fourth of July is yours, not mine” (156) “to drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty . . . sere sacrilegious irony” (156) • Why I am called upon to speak? “By the rivers of Babylon . . .” (156) -- Psalms 137: 1-6: the captive forced to sing • Douglass’s performance is not a command performance of the captive but an act of political freedom in the moment; an act of inauguration. Confirmatio merged with narratio and refutatio: epideictic speech becomes deliberative, but argument (properly speaking) is “reversed” or denied • “My subject, then fellow-citizens, is AMERICAN SLAVERY. I shall see, this day, and its popular characteristics, from the slave’s point of view.” (156) • “America is false to the past . . . present . . . and future” (¶32; 156). • “But I fancy I hear some one of my audience say . . . argue more, denounce less; persuade more, rebuke less . . .” (157) • “Where all is plain there is nothing to be argued.” – My thesis continued: Douglass declines to make an argument. He can do so because of his identification with an abolitionist audience. The fact that he proceeds to make arguments contributes to the ironic quality of the speech. What does not need to be argued: • 1. The slave is a man: legal evidence “We” are ploughing, planting and reaping, using all kinds of mechanical tools . . . Douglass’s identification (1st person plural) with “the negro race”; the rhetoric of the list (157) • 2. The slave owns his/her body -- “natural right to freedom” does not need the devices of argument (158): “There is not a man [sic] beneath the canopy of heaven, that does not know that slavery is wrong for him” (158). Confirmatio2 • 1. Internal slave trade “Behold” - enargeia: bringing vividly before the eyes; human as animal (horse, sheep, swine) Douglass’ narrative: Why here? How different from the autobiography? • 2. Fugitive Slave Law (162); “religious liberty” - the fusion of religious and civic identities The law as a “declaration of war”: religion as “an empty ceremony, and not a vital principle requiring active benevolence, justice, love and good will towards man” (163). Confirmation continued • 3. The church as bulwark of slavery: criticism of Northern ministers who teach that “we ought to obey man’s law before the law of God” (165). • 4. “National inconsistency”: comparing national religious practices • 4. Constitution as “glorious liberation document” (168) Constitution • Garrison’s position: abolitionists should not vote because America’s government was pro-slavery; rejection of a corrupt political process; freedom in the north for blacks did not grant voting rights • Douglass, 1851: refusing to pursue the vote is acquiescing in discrimination; joined the Liberty and Free Soil parties to get emancipation before major political leaders; the oppressed should participate in the political process Peroration (¶63-64; 169-71) • He still has hope for the country: drawing encouragement from the Declaration of Independence in the context of internationalism • “walled cities and empires have become unfashionable” (170) • Ethiopianism -- an Africanist African-American philosophy • Garrisonian sentiments: bonds across division within abolitionist movement Declarations in Dialogue • A text becomes an intertext: circulation, imitation, warrant • Republic of letters: public and private spheres, counterpublics (social movements; advocacy) • The redefinition of the human: who will count as “man” 21st-century publics: new genres, new media Rhetoric is your friend Rhetorical questions will help you as a writer in any context: Who speaks? To whom? In what situation? In what genre(s)? For what purpose? In what styles?