The Character Prose Poem

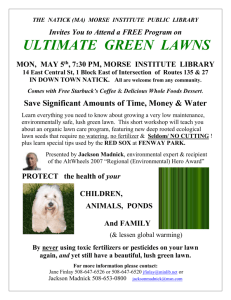

advertisement

An Adventure in Senses Prose Poem or Microfiction? Rachel Barenblat Prose poems, microfiction, "short-short" stories: regardless of what you call them, these small (usually), blocky (sometimes), paragraph-style pieces of writing have been a steady undercurrent in the literary ocean since Baudelaire published Paris Spleen, also known as Petits Poemes en Prose. "Which one of us," Baudelaire wrote, "in his moments of ambition, has not dreamed of the miracle of a poetic prose, musical, without rhythm and without rhyme, supple enough and rugged enough to adapt itself to the lyrical impulses of the soul, the undulations of reverie, the jibes of conscience?" Baudelaire dreamed this poetic prose into being, and called it the prose poem. In poetry the basic unit of construction is the line; in the prose poem, as in prose, the basic unit of construction is the sentence. So what are prose poems, beyond writing that fulfills Baudelaire's fantasy of "poetic prose, without rhythm and without rhyme..."? What distinguishes prose poems from microfiction or the short-short? The answer may frustrate you, but it's the only answer I have: there are NO DISTINGUISHING RULES. The line between the prose poem and the short-short is invisible, if not nonexistent. Some contemporary writers, like Lydia Davis, straddle the boundary between them; one of her pieces, “A Mown Lawn,” has been anthologized as a poem in the Best American Poetry series, and as a short-short in an anthology of microfiction. A Mown Lawn by Lidia Davis She hated a mown lawn. Maybe that was because mow was the reverse of wom, the beginning of the name of what she was—a woman. A mown lawn had a sad sound to it, like a long moan. From her, a mown lawn made a long moan. Lawn had some of the letters of man, though the reverse of man would be Nam, a bad war. A raw war. Lawn also contained the letters of law. In fact, lawn was a contraction of lawman. Certainly a lawman could and did mow a lawn. Law and order could be seen as starting from lawn order, valued by so many Americans. More lawn could be made using a lawn mower. A lawn mower did make more lawn. More lawn was a contraction of more lawmen. Did more lawn in America make more lawmen in America? Did more lawn make more Nam? More mown lawn made more long moan, from her. Or a lawn mourn. So often, she said, Americans wanted more mown lawn. All of America might be one long mown lawn. A lawn not mown grows long, she said: better a long lawn. Better a long lawn and a mole. Let the lawman have the mown lawn, she said. Or the moron, the lawn moron. Lydia Davis the Rebel Poet “A Moan Lawn” was chosen for The Best American Poetry 2001, edited by Robert Haas and David Lehman. At the back of that collection, where contributors are asked to comment in a few paragraphs about the writing of their chosen poem, or about their work in general, her entry reads: "Towns lawns all mown, some poisoned, all free of weeds, all free of cover, some planned plantings, no loose small animals, no loose insects, some pets, some penned dogs, some tied and housed dogs, some pests, in effigy: effigy of raccoon, effigy of deer, effigy of Canada goose (no nibbling, no nuisance, no ruin of planned plantings), unmoving goose flock feed on poisoned mown lawn, red bows on necks come holiday." The First Rebel Poet: Charles Baudelaire 1821-1867 French poet who influenced the French Symbolists. Lived a debauched, eccentric, and violent life. Called Edgar Allan Poe, his “twin soul.” Fluers du mal (1857) Art must create beauty even from the most depraved or “non-poetic” situations. Mid-conversation: “Wouldn’t it be agreeable to take a bath with me?” Petits Poéms en Prose (1869) Non-metrical composition poems. First poet to make a radical break from the form of verse. Be Drunk Translated by Louis Simpson You have to be always drunk. That's all there is to it—it's the only way. So as not to feel the horrible burden of time that breaks your back and bends you to the earth, you have to be continually drunk. But on what? Wine, poetry or virtue, as you wish. But be drunk. And if sometimes, on the steps of a palace or the green grass of a ditch, in the mournful solitude of your room, you wake again, drunkenness already diminishing or gone, ask the wind, the wave, the star, the bird, the clock, everything that is flying, everything that is groaning, everything that is rolling, everything that is singing, everything that is speaking. . .ask what time it is and wind, wave, star, bird, clock will answer you: "It is time to be drunk! So as not to be the martyred slaves of time, be drunk, be continually drunk! On wine, on poetry or on virtue as you wish. Posthumous Remorse Charles Baudelaire Translated by Keith Waldrop When you go to sleep, my gloomy beauty, below a black marble monument, when from alcove and manor you are reduced to damp vault and hollow grave; when the stone—pressing on your timorous chest and sides already lulled by a charmed indifference—halts your heart from beating, from willing, your feet from their bold adventuring, then the tomb, confidant to my infinite dream (since the tomb understands the poet always), through those long nights in which slumber is banished, will say to you: "What does it profit you, imperfect courtisan, not to have known what the dead weep for?" —And the worm will gnaw at your hide like remorse. Le Spleen de Paris by Baudelaire Let me breathe in for a long, long time the scent of your hair, let me plunge my entire face into it, like a thirsty man into the water of a spring, and let me wave it in my hand like a scented handkerchief, to shake memories into the air. If you could only know all that I see! All that I feel! All that I hear in your hair! My soul voyages upon perfume just as the souls of other men voyage upon music. Your hair contains a dream in its entirety, filled with sails and masts; it contains great seas whose monsoons carry me toward charming climes, where space is bluer and deeper, where the atmosphere is perfumed by leaves and by human skin. In the ocean of your hair, I glimpse a port swarming with melancholy songs, with vigorous men of all nations, and with ships of all shapes silhouetting their refined and complicated architecture against an immense sky in which eternal warmth saunters. In the caresses of your hair, I find again the languors of long hours passed upon a divan, in the cabin of a beautiful ship, rocked by the imperceptible rolling of the port, between pots of flowers and refreshing jugs. In the ardent hearth of your hair, I breathe the odor of tobacco mixed with opium and sugar; in the night of your hair, I see the infinity of tropical azur resplendent; on the downy shores of your hair I get drunk on the combined odors of tar, of musk, and of coconut oil. Let me bite into your heavy black tresses for a long time. When I nibble at your elastic hair, it seems to me that I am eating memories. Russell Edson’s Sleep There was a man who didn't know how to sleep; nodding off every night into a drab, unprofessional sleep. Sleep that he'd grown so tired of sleeping. He tried reading The Manual of Sleep, but it just put him to sleep. That same old sleep that he had grown so tired of sleeping . . . He needed a sleeping master, who with a whip and a chair would discipline the night, and make him jump through hoops of gasolined fire. Someone who could make a tiger sit on a tiny pedestal and yawn . . . She Dreams by Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum GYPSIES, IT SEEMS, can no longer captivate a crowd. A woman who looks like a viol, a girl who waddles on the seared stumps of her hands, a man who sings from his backside, are incapable of provoking wonder. The procession of gypsy caravans trundles from one empty venue to the next. The fearsome Marguerite, who once wore a sword, who played the hero, finds herself dangerously close to despair. Miraculously, a summons arrives. The photographer has circulated his portraits among the wealthy of Toulouse. A widow, renowned for her fecund imagination, purchases every last photograph and hangs them all in her high-ceilinged drawing room. She sits, daily, for several hours, in this gallery of grotesques. One Sunday, when the lilacs are in bloom, she becomes animated by an idea. She wishes the company to pay her a visit, at her expense. She has a proposition. Some Points of Departure from Gary Young Use the spontaneity and drive of the sentence. Allow your writing to be subtle and subversive, to warp and seduce, so the reader accepts something in a prose poem that they might resist in formal poetry. Be concise. Ask yourself if you can justify everything that is in your poem, each phrase, each word, each comma. If you're unsure, remove it. The prose poem is a lyric. But embrace the trans-genre possibilities of the prose poem. Commandeer the exposition, the recipe, the definition. Embrace the surreal, a bit of arsenic, a bit of starlight. It's the moves in the poem that excite me the most. In a prose poem you can travel such distances. Like Karl Shapiro, think of a paragraph as "a sonnet in prose" that "begins where it ends" [though of course one also wants to go somewhere else!]. our adventure begins… Skip James Joanna Newsom Tom Waits Phillip Glass