Bartolome de las Casas Hamburger/Hotdog

advertisement

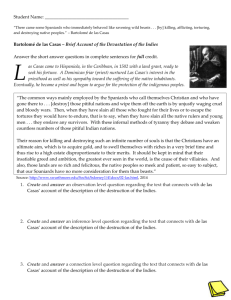

The Story of Bartolome de Las Casas and the Settling of Spanish America An historian, theologian, and Dominican monk, Bartolome de Las Casas spent a large part of his life fighting for the rights of the native peoples of the Americas. His life revolved around the conquest and settling of the Americas. As a child, Las Casas observed Columbus’ return from his initial voyage. His father was a merchant who sailed with Columbus on his second voyage. Schooled in theology and Latin, Las Casas sailed to the New World for the first time in 1502 and was the chaplain for the final conquest of Cuba. For his service, he was granted land and saw the mistreatment and exploitation of the Native Americans first hand. At this point he gave up his land and dedicated himself to improving the rights of the Native Americans and against the conquest of the New World for the rest of his life. The Spanish conquest of the Americas was driven by mercantilist philosophy and, as such, the initial economy was based on the extraction of silver and gold. As other European powers began to show interest in colonizing parts of the New World as well, the King of Spain was interested in settling the area so as to solidify his claim to the land. As a result, the King granted encomiendas to Spanish settlers, which granted the settler the right to demand taxes and labor from the indigenous people settled on the land given to them by the King. It was the abuses of this system that Las Casas railed against. By the 17th century, the most profitable cash crop in the tropical areas of the New World was sugar. Transplanted from the Old World, the demand for sugar and sugar products soared in Europe, creating a huge demand for labor to work the fields, a demand not met by traditional European methods of labor. Sugar only grows in a tropical environment and is an extremely labor-intensive crop to grow. Harvesting sugar at this time was also very difficult, causing the death of many laborers. As such, no Europeans would work the fields. The owners of the large plantations, known as haciendas, demanded more and more labor from the Native Americans. This led to a conflict over the acceptable means of acquiring labor that involved the hacienda owners, the Crown and Catholic missionaries such as Las Casas. Spain’s colonies in the New World were all under the control of the King, who appointed a Viceroy to serve as a governor in the New World. All policies, regulations, laws and taxes originated in the Council of the Indies, which advised the King and was located in Spain. The King was concerned that the colonies not be given too much latitude to rule themselves, although this was complicated by the tremendous distance between Spain and the New World. The hacienda owners, of course, chafed at this control and especially at any interference in their ability to make money off cash crops. However, Catholic missionaries, such as Las Casas, by the middle of the 16th century had become very disturbed by the treatment of the Native Americans under the encomienda system and fought for their rights. Las Casas argued that the Native Americans lived by natural law and were simply a civilization that had not reached a level of mature development. Part of the process of maturity was being brought the word of God. Spanish settler mistreatment of the Native Americans was, thus argued Las Casas, morally wrong and complicated the missionaries’ efforts to convert the population. All three positions came into conflict over the way Spain’s colonies would operate in the New World. Las Casas repeatedly argued his case to the Spanish crown. At one point, he even suggested that African slaves be used as replacement labor for the Native Americans. Africans had no claim to the land, were not Christian, and, therefore, it would not be morally wrong to make them work the land. Las Casas later came to regret this statement and felt that all slavery was wrong. The King of Spain was eventually persuaded and the New Laws of the Indies were passed in 1542. As a part of the legislation, no new encomiendas were to be granted and when an economienda owner died, the property was to be returned to its natural state. These laws, however, were not widely enforced and were resisted in the New World by the European hacienda owners. Las Casas himself was forced out of his position as bishop of Chiapas, eventually returning to Spain where he fought an unsuccessful battle for more rights for the native population. While the laws did end slavery for Native Americans, it was ineffective in granting them most basic rights. Most Native Americans ended up working as peons, a person forced to work to pay off a debt, on the large plantations. The demand for labor in the Americas continued to increase beyond the capability of the Native American population and Europeans were soon importing thousands of African slaves.