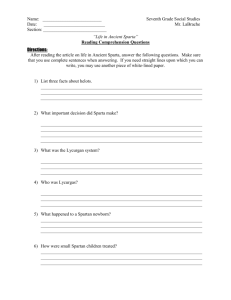

1.0 - Student Booklet on Sparta.

Spartan society to the Battle of Leuctra 371 BC

The geographical setting

In Notes

Social structure and political organisation

The issue of Lycurgus (the Great Rhetra)

Lycurgus ( or Lykourgos)

The issue of Lycurgus (the Great Rhetra). History records that the architect of the Spartan political system was Lycurgus. To some he was a man, to others a god. Plutarch wrote a Life of Lycurgus , valuable for its description of Spartan ways, although a long time after the period in question.

Even the Delphic oracle was puzzled, according to Herodotus, .......

"You came, O Lycurgus, beloved to Zeus, and to all the other Olympian Gods to my temple. Like a man or like a god should I welcome you ? But I really think, O Lycurgus, that you are a god."

Delphic Oracle.

Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus

In his Life of Lycurgus, Plutarch (A.D. 50-120) , provides us with a detailed account of the reforms attributed to the legendary lawgiver. Plutarch was aware of a number of different opinions concerning the date of Lycurgus' life, but decides on what would be a mid-ninth-century date. Plutarch combined the story of Lycurgus' visit to the shrine of Apollo at Delphi with the tradition that it was he who gave the

Spartans a constitution. According to Plutarch, Lycurgus obtained from the oracle of Apollo at Delphi a rhetra , which laid down the constitution that the Spartans should adopt.

Xenophon, an Athenian writing in the fourth century BC, was exiled from his native city and served in the

Spartan army under King Agesilaus in 396-394BC. He was presented by the Spartans with an estate near

Olympia and was the Spartan representative at Olympia. His Spartan Constitution , written in about 388, is a valuable source but must be used with caution. Written in a spirit of gratitude to Sparta, it is full of praise for the Spartan constitution and generally uncritical of the system. Above all it reflects fourth century conditions, while asserting the unchangeable and stable nature of the Spartan constitution.

Aristotle, a philosopher and political theorist writing in the 4th century B.C., allows us to see how some people of his time viewed the Spartan constitution very favourably as a balanced and stable blend of different political elements.

Roles and privileges of the two kings

The constitution – roles and privileges of the two Kings

1

The system attributed to Lycurgus was organised so that individual power was closely checked and change by peaceful means very difficult. The fact that there were two kings meant that one could prevent the other from becoming too powerful on his own account.

The two kings were representatives of the two hereditary royal families who were believed to be descended from Herakles: the Agiads and the Eurypontids.

The original powers of the kings were greatly restricted, and they became principally generals. When the army fought outside Sparta, however, one king only was allowed to go as its commander, as the possibility of a disagreement or the loss of both kings was too great a risk.

Government: ephorate, gerousia, ekklesia

At home they had some powers but were, in fact, less important than the ephoroi (ephors) or "overseers".

These were five magistrates elected annually from the people. Each month the kings and ephoroi exchanged oaths, the kings swearing that they would govern according to the laws, and the ephoroi searing that, as long as the kings obeyed the laws, they would see to it that the kingship was unharmed.

The ephoroi kept a close watch on the kings: two went along on any foreign campaign, and they had the power to call the kings before them to explain their conduct. They could even fine or arrest them.

The ephoroi were generally responsible for the discipline of the state, acting as judges, dealing with foreign ambassadors, presiding over meetings of the council and the assembly. It was they who annually declared war on the helots, and on beginning their years of office they issued a decree that all citizens should “shave their top lips and obey the laws” . It was the ephors who truly wielded real power in

Ancient Sparta. This lay, not only in their power with respect to the kings and the helots, but with the ephors' power to call the ecclesia (or apella) together, to decide on the issues that the apella would consider...and if all else failed, their right to over-ride any decisions!

The gerousia (aristocratic council) possessed strong influence in the city. Consisting of the two kings and twenty-eight men over the age of sixty, it was elected for life from certain ancient families, with 30 men in total.

Finally there was the ecclesia (or apella)(assembly or council of citizens), the members of which were the people, or at least adult males. Although the assembly had the right to approve or reject proposals put before it, there was an important law to the effect that "if people make a crooked decision, the kings and elders have the power to withdraw the matter."

Social structure:

Spartiates, perioeci, ‘inferiors’, helots

The structure of Spartan society: in summary

Spartan men

Were the original Dorian conquerors of Laconia and numbered c.9,000

A privileged social class of full-time soldiers holding all political power

At age 30, as full citizens, could sit on the apella and elected the gerousia and ephoroi

2

All "equal" under the law and subjected to the rigid discipline of the state

Lived a life that stressed courage, loyalty, endurance and obedience

Appears there were rich and poor but there is controversy over a nobility

Were supported by the state, each having a kleros (farm) with helots to work it

Forbidden to engage in farming, trade and industry

Spartan women

Could not hold public office or vote

Spartan women held a unique position in Greece

Mingled freely with men, sharing their sports

Trained as rigorously as their men in order to be fit companions and mothers

Held some 40% of Sparta’s land and wielded significant economic control

Grew up in physical freedom, yet were modest and careful of their health

Known for their beauty; jewellery, cosmetics and perfumes forbidden

Perioekoi

Dorian in origin and lived in some 100 scattered settlements

Villages were a buffer zone to prevent helots from escaping

Lived in self-governing communities having local citizenship

Perioekoi had no role in formulating Spartan policy

Owed allegiance to Sparta but were not permitted to marry Spartans

Chief contribution was economic and they were the traders and craftspeople

They also engaged in fishing, shipbuilding. The best sailors were in the "navy"

The Spartan kings' revenue came from their estates in the lands of the perioekoi

All male perioekoi were expected to serve alongside Spartiati during time of war

Inferiors

Illegitimate children of Spartiati fathers and helot mothers

Helots who had been freed for some courageous act or for service to the state

Could include helots "adopted" as playmates of Spartan boys and who shared in training

Spartiati peers: cowards who had lost citizenship (not necessarily permanently)

Helots

Pre-Dorian inhabitants of Laconia and people of conquered lands

State-owned serfs who, along their families, worked Spartan lands (kleroi)

Were forbidden to move without government permission

Duty was to supply a fixed produce annually to their Spartiati masters

Were able to keep or make a profit from any surplus produce

Often acted as servants to their Spartiati masters in time of war (as skirmishers)

Could be freed for acts of outstanding courage or service

Often treated harshly and were always suspected

3

Spartiati upbringing

Everything was dedicated to making each Spartiati a superb and unquestioningly loyal soldier. The process started at birth. Newly-born babies were inspected by a committee of elders and, if considered too weak, they were left to die of exposure on the slopes of Mount Taygetos

Babies who passed inspection were carefully brought up, as Plutarch describes:

“The women did not bathe the babies with water, but with wine, making it a sort of test of their strength.

For they say that the epileptic and sickly ones lose control and go into convulsions, but the healthy ones are rather toughened like steel and strengthened in their physique. The nurses displayed care and skill: they did not use swaddling-bands, making the babies free in their limbs and bodies. They also made them sensible and not fussy about their food, not afraid of the dark or frightened of being left alone, not inclined to unpleasant awkwardness or whining. So even some foreigners acquired Spartan nurses for their children.”

Role of the Spartan army

The Spartan army

The reputation of the Spartan hoplite was well established. Their equipment was excellent, especially compared to that of non-Greeks. They had willpower and no fear of dying on the battlefield; to die in this way was the greatest honour a Spartan could hope for. At the back of every Spartan's mind, as he prepared for battle, lay the words of Spartan women ...

that a Spartan hoplite should return home carrying his hoplon or being carried on it!

When retreating, a hoplite discarded his hoplon (shield) as it was very cumbersome when attempting to run. To retreat was, for a Spartan, unthinkable. Hence the loss of a shield was considered cowardice. If a Spartan was killed in battle, his comrades carried his body on his hoplon back from battle for burial.

Educational system: agoge

The educational system: agoge and the Spartan Army

Comradeship in the Spartan army was extremely strong. According to Spartan tradition, Lycurgus had been most particular in fostering it. The agoge (Spartan system of education) had comradeship and belonging as one of its cornerstones. Young boys were drilled in packs. As a youth of 20 a Spartan male sought membership to one of the dining clubs. This syssition, as it was called, comprised some 15 members who spent considerable time with one another, even when not in training. When in battle, the syssition was the hoplite's "tent".

In a recent publication by Stephen Hodkinson and Anton Powell ( Sparta: New Perspectives ), H.W.

Singor looks at the syssition's composition in detail. Singor emphasised the close bond that developed between members. This bond continued into old age and had implications in the formation of chains of patronage down through the different age groups.

The structure of the Spartan Army

Thucydides, a Greek historian and soldier, gives us a detailed overview of the structure of the Spartan army around 400 B.C.

4

He says that the organisation was based in a row eight men deep. Four of these rows formed an enomotia or platoon; four enomotiai formed in their turn a pentekostis or company which was commanded by a pentekonter ; four pentekosteis formed a lochos or battalion under the leadership of a lochagos . The average army had about seven of these lochois, giving a total of 3,548 men excluding commanders.

Xenophon, who had also been an officer, tells us about a different structure.

Now the average row was twelve men deep, while only two of these rows were needed to form an enomotia . Two enomotiai formed a pentekostis , two pentekosteis formed a lochos , while four lochois formed a mora , or regiment, under the command of a ptolemarch (or polemarch). An army consisted of six morae. The reduction of the Spartan population did decrease the total strength of the Spartan army, but not the strength of a mora , which consisted of some 500, 600, or 900 men. The number varied as it depended on the age of the hoplites who were used.

Regardless of the precise composition of the phalanx, in battle the drill was the same. The enomotiai marched behind each other in a large row. Before the battle the last troops of each enemotia positioned themselves on the left behind their leader to form a phalanx of four columns, in total 16 rows wide, and 8 rows deep. A space of two metres was maintained between the columns, but on the order "close ranks" the last troops walked to the left front to close gaps in the front row. The phalanx was in a closed formation and ready for the battle.

Whatever structure the Spartans might have used, it did not decrease their effective communication system. The king gave his orders directly to the ptolemarchs , who passed them on through the troops via the lower officers.

The biggest problem lay in the fact that each soldier was trained so well that the Spartan army practically consisted only of trained men (without an officer). Yet, the average soldier was so well drilled and trained that he knew as much about warfare as an officer! Such an organisation does not always give the best results on the battlefield. An example of this is the Battle of Plataea (479 B.C.) where the Spartan commander refused to follow the order of the Spartan king, Pausanias, to retreat. At the Battle of

Mantineia (362 B.C.), the ptolemarchs at the right wing ignored the orders of the king as they wanted to win the battle in their own way. Later, these ptolemarchs were sued and banished from Sparta.

Orders were hard to understand in the uproar of a battle, and the Corinthian helmet (see illustration below) also reduced the hearing of the soldiers. This is the reason horn signals and hand signals were often used. However, they were sometimes misunderstood, as was the case in an incident at Amphipolis, where the unprotected right side of the Spartan phalanx was exposed to an Athenian attack, with dramatic results.

Technology: weapons, armour, pottery

The Spartan hoplite - weapons and armour

The panoply of the Spartan hoplite (consisting of helmet, corselet, greaves, round hoplon , short sword and thrusting spear) was not very different from an Athenian hoplite. The most noticeable differences were the Spartan symbol on the hoplon, and the red cape (which was not worn during a battle). Long hair was common on Spartan men. Plutarch attributes this fashion to a saying of Lycurgus: "In times of battles the officers relaxed the harshest aspects of their discipline and did not stop the men from beautifying their hair and their armour and their clothing, glad to see them like horses prancing and neighing before races. For this reason they took care over their hair from the time when they were youths, especially

5

seeing to it in times of trouble so that it appeared sleek and well-combed...... it makes the handsome better-looking and the ugly more frightening."

Control of the helots: the military, krypteia syssitia,

Another responsibility that formed part of the Spartan education system was participation in the Krypteia, or "period of hiding". At this time the boy had to live alone and under cover in the countryside. During this time in the Krypteia, groups of boys roamed the countryside living off the land, stealing, spying and

"maintaining order". This keeping of order invariably involved the killing of helots. Strong or athletic helots, or those who showed qualities of leadership or arrogance, were the victims. The Krypteia kept order, toughened its members, taught them to be effective and ruthless fighters while further forging comradeship amongst its members.

The Krypteia

Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus of Sparta , 28:

"Now in all this there is no trace of injustice or arrogance, which some attribute to the laws of Lycurgus, declaring them efficacious in producing valor ( andreia ), but defective in producing righteousness

( dikaiosyne ). The so-called KRYPTEIA at [Sparta], if it really was one of Lycurgus' institutions, as

Aristotle says it was, may have given Plato ( Laws 630.d) also this opinion of the man and his constitution.

This is as follows: The magistrates from time to time sent out into the countryside at large the most discreet of the young men, equipped only with daggers and necessary supplies. During the day they scattered into obscure and out of the way places, where they hid themselves and lay quiet. But in the night, they came down to the roads and killed every Helot whom they caught. Often, too, they actually made their way across fields where the Helots were working and killed the sturdiest and best of them. So, too, Thucydides, in his History of the Peloponnesian War [IV.80], states that the Helots who had been judged by the Spartans to be superior in bravery, set wreathes upon their heads in token of their emancipation, and visited the temples of the gods in procession, but in a little while afterwards all disappeared, more than two thousand of them, in such a way that no man was able to say, either then or afterwards, how they came to their deaths. And Aristotle in particular says also that the Ephors, as soon as they came into office, made formal declaration of war upon the Helots, so that there might be no impiety in slaying them."

Despite modern teaching to the contrary, the boys were taught music and poetry as well, but these were mostly military in tone and based on religious or patriotic themes, in keeping with the rest of their education. The writings of the poets Tyrtaeus, Alcman and Terpander are important in constructing a view of Sparta at this time.

Agesilaus (Eurypontid king of Sparta, 400-360 B.C.)

At the age of 20 came the most critical time in a Spartan man's life. At this age, he was permitted, for the first time, to marry. More importantly, he now tried to get elected to one of the dining clubs, rather like an army "mess", to which the men belonged. There were about fifteen members of each syssition, also known as a phydition. In order to gain membership of syssitia there was a ballot. In the ballot each member of the mess dropped a pellet of bread into an urn, and if a single man squeezed his pellet flat, the candidate was rejected. To fail to win election to any mess at all meant becoming a social outcast.

Members of the mess ate all their meals communally, and each man had to provide, monthly, a fixed quota of barley, wine, cheese and figs that were grown on the Spartan's kleros, the plot of land alloted to each Spartan at birth and worked by helots. The diet was plain, including usually a type of broth, which was well-known outside Sparta for its "nastiness". The broth consisted of pork, blood, salt and vinegar. It

6

was apparently dark in colour. The black colour was no doubt due to the blood that was an ingredient in the stew. Exaggerated sources suggest all nature of ingredients! Incidentally, this exaggeration about

Spartan food is quite typical of the many exaggerations about Spartan life that circulated in the ancient world.

The syssition ( syssitia in the plural) was a "military section", and the Spartan was now no less at the service of the state than he had been as a boy.

"Their training continued right into manhood, for nobody was free to live as he wished, but the city was like a military camp, and they had a set way of life and routine in the public service. They were fully convinced that they were the property not of themselves but of the state. If they had no other duty assigned to them, they used to watch the boys, either teaching them something useful, or learning themselves from seniors. For indeed one of the fine and enviable things which Lykourgos achieved for his citizens was a great deal of leisure. He forbade them to practise any manual trade at all. There was no need for the troublesome business and efforts of making money, since wealth had become completely without envy and prestige. The helots worked their land for them, supplying the fixed amount of produce."

(Plutarch)

Role and status of women: land ownership, inheritance, education

The role of women was important in Spartan society. They certainly were not marginalised.

Plutarch tells us that, as far as girls were concerned, Lykourgos

" ..... took all possible care. He made the girls exercise their bodies in running, wrestling and throwing the discus and javelin, so that their children, taking root in the first place in strong bodies, would grow the better, and they themselves would be strong for childbirth, and deal well and easily with the pains of labour".

Young women, like girls, continued their physical and mental training. Like men of Sparta, women prided themselves on their fitness, their ability to endure pain and discomfort. In stark contrast to their counterparts in Athens, Spartan women were free to mingle with the men, often sharing their sports. In athletic activities and in processions the girls, like the boys, were nearly naked. One of the most strenuous athletic exercises Spartan women performed was the bibasis. It involved jumping up and down, touching the buttocks with the heel. Girls were brought up in an environment where they too were an integral part of this "military society". Just as with the boys, the girls were toughened physically and emotionally;

Spartan women were expected to suffer the losses in battle just as strongly as the males in the society.

There was no concept of the "lesser sex".

Spartan women might be expected to have babies to men other than their husband. Their training had aimed at ridding them of any emotional weakness. Women were expected to deliver their sons, brothers, fathers, and husbands to the service of the state and, if need be, to death in battle. According to

Xenophon, it was a great act of friendship to offer one's wife to a comrade-in-arms for the purpose of siring further children.

Lycurgus, it was said, saw jealousy as a curse on society. This extended to one's wife and even children.

Women, however, were excluded from holding public office and did not have the right to vote. Though

Spartan women did not participate in government, Spartan women did enjoy considerable freedom, could accumulate property and exercise considerable power, even though they were deprived of a part in the

7

actual government of Sparta. Women of Sparta enjoyed freedom and power unknown elsewhere in

Greece at the same point in time.

Interestingly, Spartan women were forbidden to spin or weave. Such tasks were seen as tasks fit only for slaves.

Elsewhere in Greece, Spartan women were famous for their natural beauty, strength and grace. Lycurgus had forbidden women to wear jewellery, cosmetics and perfume.

The economy:

Land ownership: agriculture, kleroi, helots economic roles of the periokoi (‘ dwellers around’) and helots

The helots and the economy

The Spartan economy was based on the labour of the helots. Helot families were granted land from the state and worked this land while the Spartiati (Spartiate) master was on military duty. Helots were permitted to keep surplus produce once their quota was filled. Originally this quota was 50%! Helots could not move from place to place without government permission. They acted as servants to Spartiati during war...they sometimes served as lightly-armed skirmishers in battle. A helot who distinguished himself in battle might be freed (these persons were termed neodamodes).... but was dangerous.

In his History of the Peloponnesian War, [4, 80] Thucydides makes these interesting comments:

“that the Helots who had been judged by the Spartans to be superior in bravery, set wreaths upon their heads in token of their emancipation, and visited the temples of the gods in procession......” .

Thucydides goes on to note that only a short time later some 2,000 helots who had been so freed had vanished without trace! Clearly the krypteia had been busy indeed.

Helots, though fundamental to the economic order of Laconia, presented a constant threat to Spartan security. They were discontented and rebellious.

Scholars have suggested that the helots outnumbered Spartiati 20 to 1. In real terms this would mean that, if there were 9,000 Spartiati, then the helots numbered some 180,000!

The helots and their working of the land were fundamental to the operation of the "Spartan system". At the very heart of the Spartan economy were the land and its produce.

At birth each Spartiati was assigned a klaros (or kleros), which was a package of land, along with helots to work it. This economic independence freed the Spartiati to concentrate all their time and energies on training and fighting. A Spartiati could not sell, divide or lose this land; it was passed on to male heirs. If there were none, then it went to the daughter. Interestingly, women came to own some 40% of all Spartan land. Though they were not able to vote, the economic power of Spartan women was enormous.

8

The perioekoi

The perioekoi (perioici) (or perioekos if only one!) were the so-called "dwellers around". (Sometimes the word is translated as "neighbours" or "those on the periphery".) The perioekoi communities (there were over 100 of these communities scattered over the area controlled by Sparta) provided a "buffer zone" against escaping helots. They performed non-agricultural trades and duties that included mining, fishing and trading. They were also fine ship-builders and were renowned as the best sailors in the Spartan

"navy". In time of war they served as light infantry. There was a perioekoi presence at both the Battle of

Thermopylae (480 B.C.) and the Battle of Plataia (Plataea) (479 B.C.)

The perioekoi maintained a form of political independence. Their communities were self-governing. In these communities they had their own citizenship. Even though there was this "degree of freedom" the perioekoi owed allegiance to Sparta. In the event of a dispute between a perioekos and a Spartiati, the case would go before the ephoroi for resolution.

Spartans were forbidden to engage in trade. They were also forbidden to travel abroad, except on state instructions. Foreigners were not admitted to Sparta without supplying a very good reason for doing so.

This was to prevent the citizens from being corrupted by foreign ideas and morality.

As the Spartiati (Spartans) were forbidden to engage in trade, the perioekoi gained considerable "wealth".

However the development of a wealthy merchant class in Sparta was hampered by Sparta’s adherence to the iron coinage mentioned by Xenophon (see below). One reason why wealth was less desirable lay in the fact that Sparta's authorities refused to adopt the system of making silver into coins in the manner of other Greek cities. Instead she continued to use unwieldy iron bars for money. Such a clumsy currency discouraged trade between Sparta and other city states. Trading in such a medium was, on one hand, unwieldy, while on the other, silver was clearly preferable to iron.

Of the Spartan system of currency, the historian Xenophon commented "a thousand drachmas' worth would fill a wagon" .

The 'inferiors'

Another group in the Spartan social order were the inferiors, people who were neither slaves nor citizens.

They included:-

Partheniai, illegitimate children of Spartiati fathers and helot mothers.

Mothoces, sons of helots often "adopted" as playmates of Spartan boys. They shared in training.

Neodamodes, helots whose courageous service or act had earned them their freedom.

Tresantes, cowardly Spartiati who had been deprived of their citizenship (not necessarily permanently).

9

Religion, death and burial

Religion

Religion in Sparta was a way of bringing the community together and uniting the gods with the everyday social and political institutions of the Spartan state.

The fact that the kings served as chief priests reinforces this amalgamation of religion and government.

Major festivals celebrated by the Spartans included those common to other Greek city states, along with festivals peculiar to the Spartans.

Gods and goddesses: Artemis Orthia, Poseidon, Apollo

The cult of the godess Artemis Orthia

Artemis was the goddess of fertility and childbirth, protector of children and women’s health. She was associated with forests and uncultivated places. She is sometimes called the 'mistress of the wild thing' and is shown in art as a woman (sometimes with wings) holding animals. Orthia was an earlier Spartan goddess about whom little is known. The combining of the two deities became a particular Spartan religious observance.

The sanctuary of Artemis Orthia stood near the Eurotas River outside the centre of Sparta.

Here there were temples, altars and an area for spectators. Below is a photograph of the ruins of the

Temple of Artemis Orthia as it appears today. Beyond, in the distance, are the Taygetos Mountains.

The cult had the following features: May / June was a time of separation of young men in the wild and a cheese-stealing ritual at the altar of Artemis Orthia. The altar was defended by older youths with whips.

An endurance test took place in front of family and friends. Songs and dances were followed by a parade of the young men in fine clothes after their ordeal. At the site archaeologists have found many small votive lead figurines and masks used in the cult.

Myths and legends: Lycurgus and the Dioscuri

Spartan families trace their heritage to the hero Herakles, who entered the underworld at Cape

Taernon at the tip of Laconian Peninsula.

Sparta ws home to Helen of Troy and her twin brothers Castor and Polydeuces (Pollox) – known as the Dioscuri. All 3 were children of Zeus

Sparta also claimed the heroes of the Trojan War. Helen and Menelaus were commemorated at

Menelaion

Lycurgus the lawgiver was a legendary Spartan figure who received ritualistic worship

Legend also grew around the courageous stand and ultimate death of the 300 Spartans at

Thermoplyea

10

Festivals: Hyakinthia, Gymnopaedia, Karneia

The Hyakinthia festival

This was a festival named after Hyakinthos, a youth who was lover of the god Apollo and died when

Apollo accidentally hit him with a discus.

The flower of the red hyacinth was believed to have sprung from his blood. In his grief, Apollo ordained an annual festival.

This festival was held at the ancient shrine of Amyclae (about five kilometers from Sparta). This site was the location of a huge statue of Apollo, the tomb of Hyakinthos and an open area for festival dances.

The festival took place over three days in the (summer) month of July.

Athenaeus, writing in the 2 nd century A.D., has given an account of this festival which basically revolves around mourning for Hyakinthos and praise of Apollo:

The festival had TWO stages:

1.

The first stage involved rites of sorrow and mourning in honour of Hyakinthos. There was a ban on the wearing of wreaths and on joyful songs. Offerings were placed at the dead youth’s tomb.

The eating of bread and cakes was forbidden; there was a special funeral meal, then a day of ritual grief.

2.

The second stage involved rejoicing in honour of Apollo, the wearing of wreaths, the singing of joyful songs, sacrifice to Apollo, a festive meal, a procession to Amyclae, choral song and dance.

The historian Hooker has interpreted the festival as a festival for the dead on one hand, combined with a thanksgiving for life on the other.

The Gymnopaediae festival

This was 'The Festival of the Unarmed Boys'. The festival was held in the Spartan agora (market place). It commemorated the battle of Thyrea fought against Argos c.550 B.C.

The festival featured: choral performances; the setting up of images of Apollo and Artemis “boxing” amongst boys and men. Although much has been written about the violent aspect of the festival, it has been interpreted as a 'rite of passage'; on the way to manhood, an initiation that indicated membership or belonging to the community. In it we see the whole warrior code to initiate the young soldier to a life of physical excellence, a life that would involve enduring pain for the good of the Spartan state.

Interestingly, older men (about 30) who were unmarried or without children (agamoi) were not permitted to participate. Perhaps it was felt that they had not made that very important contribution to the Spartan state: healthy children!

The Karneia festival

The Karneia, a harvest festival celebrated for nine days during the month of August (late summer), was an extremely important festival for the Spartans. It was a celebration of migration, the colonisation of the city, the foundation of the Doric peoples and of various military events. For this celebration, the men were

11

divided up into nine groups of three phratries who dined together and each occupied a skias , an area which contained tents. In addition, some citizens carried models of rafts, which also symbolised the coming of the Dorians. These activities were to represent the early history of Sparta, including the migration and colonisation. Another aspect of this festival was the foot-race, which resembled a chase of prey, rather than your standard race. One young man, who first prayed to the city-gods, ran while other unmarried men, who were called the staphulodromoi (grape-cluster runners), chased him. The young man ahead of the rest was dressed in woollen fillets (ribbons around the head), which was similar to an account of human sacrifice by the Thessalians as described by Herodotos and is possibly derived from an earlier celebration of Karneios . If they caught the frontrunner, it was a good omen for the state and, if not, the future was bleak. The consequences of this race and the chasing of a human are rather interesting as it was primarily the agamoi who participated. Five unmarried people, called the karneatai , were chosen from each phyle to cover the costs of the festivals, including both sacrifice and chorus. (In early Sparta, the Karneia was a musical festival which included both men and women and a dance of armed men.)

Demetrios of Skepis described the Karneia and the games as a reflection of the military training system, which has been echoed by many modern scholars in an attempt to understand this festival. Overall, the

Karneia had a communal aspect, emphasising heroic exploits. However, another point to be made is the pacifist nature of the Karneia. During the festival, Spartans were not allowed to venture to wars or battles.

This was the reason behind the late arrival of the Spartans at the Battle of Marathon in 490 B.C.

Religious role of the kings

Covered in Essay

Death of a Spartan king

It is Herodotus who gives us details of the events that took place following the death of a Spartan king.

When a Spartan king died, horsemen travelled all over Lakonia, informing the inhabitants. In the city of

Sparta itself, women went around beating a cauldron. After this, two people from each house, a man and a woman, were expected to join in the mourning. Failure to do so resulted in heavy penalties.

All residents of Sparta joined in the mourning, striking their foreheads as a sign of their grief.

For a period of ten days following the burial of the king, meetings were not permitted for markets or to ordain or to select magistrates.

When a Spartan king died, horsemen traveled all over Lakonia, informing the inhabitants. In the city of

Sparta itself, women went around beating a cauldron. After this, two people from each house, a man and a woman, were to put on 'the signs of defilement,' or they would be charged and face heavy penalties. All the subject neighbours, helots and Spartans gather in one place and 'smite' their foreheads and lament loudly. If the king has died in battle, the town makes an image of him and carry it on a bier. After the burial, for ten days there is no meeting for market, assize,or selection of magistrates. (Herodotos, VI.58)

Cultural life

Art: sculpture, painted vases, bone and ivory carving

Cultural life changed as political life changed

Rich cultural life in 5 th and 6 th centuries BCE steadily declined through the 5 th century BCE

After Messenian wars had less time to spend on cultural activities – became more focussed on military

12

Art

6 th C. Laconian bronzes given as diplomatic gifts

Pausanius records bronze image of Athena in temple

Bronze statues of Spartan girls dancing or running – most famous

Large numbers of lead figurines found at sanctuaries – mass produced from moulds

A marble bust of a helmeted Hoplite found on the acropolis at Sparta

At least 9 Laconian sculptors are known by name to modern historians

Architecture: Amyklaion, Menelaion, the Sanctuary of Artemis Orthia

Little remains today – evidence of small but distinctive buildings

Same as trends in the rest of Greece – some evidence of Ionian influence (column capitals)

Pausanius 2 nd C. CE – tombs, temples, public buildings, monuments

Key Buildings

Shrines to Helen and Menelaus

Temple to Athena of the Bronze House

Temples to Artemis Orthia

The Amyklaion – most important temple in Lacedaemon – houses huge

Bronze statue of Apollo

The Spartan Assembly Hall

The Persian Stoa – built after victory over Persians 5 th C. BCE

Painted Vases

Laconian Pottery 0- very popular found throughout Greek World, Italy, Egypt, France

Early pottery decorated with black figurines on cream background occasional purple highlights

Later pottery Attic style – red or black figures

Painted scenes of active Spartan life

Ivory Carvings

Skilled workers made small carvings from ivory and bone

More found at Artemis Orthia than anywhere else in Greece

Sanctuary of Artemis Orthia

This is probably the most interesting site in Sparta, and it certainly enthralled later Roman visitors. It is reputed to be as early as the 12th century BCE, but it most likely only as early as the 8th century. It was rebuilt in the 6th after a flood, and the current temple was constructed in the Hellenistic period. This is the site where the famous whipping rituals took place as the center of the agoge . In the 3rd century CE, a semicircular theater was built around it, so the

Romans could view the re-enacated whipping rituals. Pausanias wrote that they used to have a human sacrifice, but

Lykourgos substituted the whipping of boys for this (3.16.9). It was here where the young Spartans used to perform dances, and wear masks, which can now be found in the Sparta museum. Also, a great number of interesting votive figures have been found here, including warriors, musicians and female figures, some as early as the geometric period. Victory inscriptions have also been found here, some dating as early as the 4th century BCE. Artemis Orthia and Eilethyia were also closely connected, and dedications to the latter were found here

Writing and literature: Alcman & Tyrtaios

Alkman

Alkman appears to have come from Sardis in Lydia and was active in the seventh century BCE. His works were arranged into six books. This included the partheneia, hymns and prooimia. The language

13

used in strongly Doric, with Aiolic and Homeric influences. One of the most important outcomes of

Alkman's work is his portrayal of Spartan women.

'Do not judge the man by the gravestone. The tomb you see is small but holds the bones of a great man.

For know that this is Alkman, supreme artist of the Lakonian lyre, who commanded the nine Muses. And twin continents dispute whether he is of Lydia or Lakonia, for the mothers of a singer are many.'

--Antipatros of Thessalonike

Tyrtaios

Tyrtaios was present in Sparta during the Second Messenian war. There has been talk that he was originally from Athens, but this now seems to be false. He mainly wrote marching songs and elegies. He used the Homeric tradition, but with a more corporate and collective ethos. Overall, he was present for the transition period of Sparta when she transformed into the militaristic state.

'The Spartans swore that they would take Messene or die themselves. When the oracle told them to take an Athenian general, they chose Tyrtaios, the lame poet, who rekindled their courage, and he took

Messene in the twentieth year of the war.'

-Suda Lexicon

'And Philochoros says that when the Spartans overpowered the Messenians through the generalship of

Tyrtaios, they made it a custom of their military expeditions that after the evening meal when the paean had been sung each man would sing a poem by Tyrtaios, and the leader would judge the singing and give the winner a prize of meat.'

--Athenaios, Scholars at Dinner

Greek writers’ views of Sparta

:

Herodotus – see AUC for writings

Thucydides o o o admired the Spartan way of life...but was glad not to be part of it! admired Sparta’s internal strength and self-sufficiency saw Sparta as an 'out-dated' society...unchanged for some 400 years o o accused the Spartans of lack of imagination.

Xenophon o o o praised the modesty and obedience of Spartan youth acknowledged the rationale for Spartan education: good soldiers enjoyed the fact that youth had respect for their elders and rulers

"If someone were to ask me whether I felt that the laws of Lycurgus still remained unchanged, I could not confidently say yes. I know that in the past the Spartans preferred to stay in Sparta in moderate prosperity rather than expose themselves to the flattery and corruption involved in governing other cities. In the past they were afraid of being proved to have gold, but there are those now who even pride themselves on possessing some. In the past the purpose of the expulsion of foreigners and the ban on foreign travel was to prevent citizens from being infected

14

with idleness by foreigners; now I understand that the apparent leaders of the state are eager to govern foreign cities for the rest of their lives. There was a time when they worked to be worthy of the lead, but now they are far more interested in ruling than in being worthy of their position.

This is the reason why, whereas formerly the Greeks used to come to the Spartans and ask them for leadership against reputed wrongdoers, now many are encouraging each other to prevent a revival of Spartan power. There is, however, no cause for surprise that such reproaches are being cast at them; they obviously do not obey either the gods or the laws of Lycurgus."

(Xenophon)

Aristotle was critical of Sparta: o o o o

They should not have kept helots while they had hostile neighbours.

Women had too much freedom: they dominated their men.

Women’s land ownership reduced the number of full (male) citizens.

The Spartans’ concern with war left them with nothing after battle.

Pausanias- see AUC for writings

Plutarch – see AUC for writings (and book)

Everyday life

Daily life and leisure activities

Athletic competitions, usuallyheld at religious festivals promoted physical fitness teamwork and discipline

Religious festivals provided leisure activities – opportunity for entertainment and social bonding

Hunting – physical fitness and social bonding for men

Horse riding for hunting and racing. Men and women involved in Chariot racing

Women – athletics (until marriage),

Food and clothing

Food

Nutritious but basic – produce of the Kleroi – radishes celery beans olives barley wine cheese

Supplemented by hunted game

Clothing

Spartan women dressed as other Greek women – peplos was split at the side for ease of movement

Teenage girls, as seen in bronze statues wore short tunics and scanty bodice which showed on breast

Most representations of men show them in battle dress / few show them dressed for hunting in short tunic

Marriage customs

marriage for procreation – girls older than other Greek women – when they were fully matured 18

most arranged by families, some done in secret – little is known of the ceremonies

males slept in barracks until 30, Plutarch and Xenophon suggest men visited their wives in secret

Spartans had practices to ensure birth rate > lending fertile women to friends and men fathering other women’s children

Children regarded as not the property of parents but of the whole state. Selective breeding – healthy children most important

15

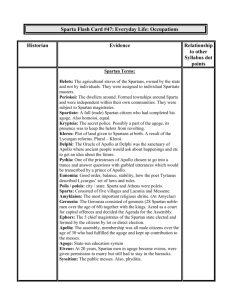

Occupations

All Spartans were full time soldiers – few filled roles of government officials

Absence of husbands caused women to play an important role in the management of estates and control of helots

Perioikoi were the workers fishermen and traders – little is known of their women

Helots were agricultural workers domestic servants and nurses for Spartans – little else is known

16

Organisation of Sparta's government: a summary (the two kings, ephorate, gerousia, ekklesia)

Dual monarchy

One King from the Agiad and one from the Eurypontid families

Performed religious duties and led in time of war

After c.500 B.C., only one king went to war

Activities of the kings were watched over by the ephoroi (ephors)

Limited civil powers: adoption, marriage of heiresses & control of public roads

Were supported by the state

Gerousia

"Council of Elders"...was next to the king in power

Comprised 30 members (including the 2 kings) aged 60 years and over

Came from the nobles ( if a nobility actually existed)

Elected by the apella for life terms (by public acclamation)

Advised the kings, and acted as a high court of justice

Could veto any unacceptable decision of the apella

Acted as a court of justice in criminal cases (death or exile)

Ephoroi

Five ephors, one from each of the five villages forming Sparta

Duty to watch over the activities of the kings

Served one-year terms only

Were elected by the people

Later role was to represent the people against the rulers

They were responsible for the discipline of the state, education of the young

Dealt with foreign ambassadors

Presided over meetings of the council and apella

It was the ephoroi who, annually, declared war on the helots

The ephoroi also had control of the krypteia

They formed the supreme civil court in Laconia

On beginning their term in office they issued a decree that all citizens should....

" shave their top lips and obey the law "

NOTE: Each month the kings and ephoroi exchanged oaths

The kings swore to govern according to the laws

The ephoroi swore to protect the monarchs if they did so.

Apella - ekklesia also known as the ekklesia

"The Assembly" was open to all male citizens (over 30)

Met monthly (at the full moon); elected officials and determined foreign policy

Did not debate, but listened to the kings and ephoroi

Ephoroi chaired the meeting of the apella

Elected the gerousia and ephoroi by public acclamation

Decisions of the apella could be overridden by the gerousia

Women, the perioikoi, and helots were not represented

17

The Lycurgan reforms

EUNOMIA ( GOOD ORDER )

Purpose Effects

Military

The three old Dorian tribes were abolished. Five new tribes were substituted, based on new locality. Each new tribe provided a regiment, each of which was elaborately divided into platoons and sections.

The Spartans needed a strong military organisation to control their subject populations (perioiki and helots), to maintain their position as the controlling elite and to protect their state from outside influences.

The Spartan state was so conservative it could be said that it had stagnated.

Discipline was secured by a system of lifetime training.

Social

Wealth

These measures prevented the accumulation of wealth by an individual so that "all Spartans could be equal".

Citizenship depended on a man owning enough land to live on the produce and devote his energies to public service.

It was physically impossible to accumulate wealth. Other Greek city states which had moved towards the Attic Standard were loath to trade with Sparta.

This land or kleros was owned by

The system was open to corruption, as "wealth" could not be accumulated legally.

Spartan women enjoyed considerable power and position in

Spartan society.

There was no growth of a mercantile "middle class" in

Ancient Sparta. Such a situation

18

the state and allotted to each

Spartan for his life.

Spartan women became very important in the ownership and inheritance of property.

Luxuries encouraged the Spartans to look forward to the prospect of booty when at war outside the state. suited the Spartans.

Money

The old iron currency was maintained.

Trade

Luxuries were prohibited in

Sparta, but the Spartans were permitted to beautify themselves in times of war.

The Lycurgun reforms Purpose

The rhetra (The Law)

Legend has it that the rhetra was the work of Lycurgus. Modern scholarship casts doubt on the fact that the system came into being at a single point in time. Even more recent research has cast doubt on the existence of Lycurgus at all!

One king led the army when in war while the other remained in Sparta.

Each one ensured the other remained loyal.

These three bodies (the gerousia, ephorate and apella) combined into a single government.

Effects

The system of government, then, had elements of monarchy, oligarchy and democracy, with no one group taking precedence (at

The two kings were taken from the

Agiad and Eurypontid families. least in theory) over the other.

Evidence suggests the monarchy existed before Lycurgus. The kings claimed descent from Heracles

(useful propaganda).

Powers of the kings were limited, especially by the ephors.

19

The gerouisa consisted of the gerontes (28 Spartan males over the age of 60). These were chosen by merit and included the two hereditary kings. The Gerousia initiated the business for discussion in the Apella.

The gerousia acted as a court to try murder cases and could impose the death penalty, banish the guilty party or impose fines. Real power rested in their power to summon, dismiss or reject legislation of the

Apella.

Although the gerontes were meant to be experienced men, they frequently lacked training in government. It has also been suggested that they might often be senile. In any case, they were an ultra-conservative group who could be relied on to maintain the status quo.

The ephors Evidence suggests that there were 5, one from each of the villages. Were elected for one year, with election being open to any Spartan citizen.

Ephors presided over the Apella.

They heard civil law cases. They could impeach the kings. They directed the krypteia.

Two ephors accompanied the king into battle.

The ephors usurped the power of the other two bodies and were subject to bribery and corruption.

(As all Spartan citizens were open to election, the presumption is that the poor ones might be bribed.)

The apella consisted of all citizens

(i.e. male Spartiati over the age of

30). It voted by acclamation (i.e. clapping). Had effective power only on matters of war and peace.

The apella voted on proposals of the gerousia and elected ephors and members of the gerousia.

The apella lacked formal training and possessed little real power.

THE SPARTAN SYSTEM

EUNOMIA: "Good Order" The Spartan name for their way of life (constitution)

AGOGE "Training" The Spartan name for their system of physical, social, intellectual and moral education of the citizen.

Lacedaemonians: The inhabitants of the territory belonging to the Spartan state, the valley of the

Eurotas River in s. central Peloponnese and other conquered territory (Messenia).

`Lacedaemonian' sometimes means any inhabitant, but sometimes is also used loosely to mean

`real' Spartan full citizens, Spartiates: A Spartiate IS a Lacedaemonian, but not every

Lacedaemonian is a Spartiate.

Spartan: Technically, an inhabitant of the POLIS called "Sparta", which was really an amalgamation (SYNOECISM) of five villages or townships inside the geographical area called

Lacedaemonia. When used loosely, the term Spartan meant a Spartiate, full citizen.

Spartiate: The word used to refer to a full citizen of the polis of Sparta, who had gone through the

AGOGE and was serving in the Spartan military (also his female relatives). Not every Spartan was a Spartiate. The total number of Spartiates was never more than 9,000 in a population of

20

225,000+ Lacedaemonians and subjects. By the 4th cent. B.C. the number was down to around

750. The Great Earthquake (ca. 465) and the Great Peloponnesian War (432-404) had a great deal to do with this.

PERIOIKOI: `Those dwelling round about': natives of Lacedaemonia who did not have full citizen rights; farmers and merchants mostly perioikoi.

HELOTS: conquered subjects used as serfs, both in the Eurotas valley and in Messenia to the west; legally they were enemies of the State and subject to arbitrary brutal treatment. They were the property of the Spartan State.

KINGS:

TWO kings! Two royal families (Agiads, Eurypontids), [Archagetai] both claiming descent from

HERAKLES, the cultural hero and ancestor of the Dorians. Kings served for life, and the office was hereditary; but kings had to be trained in the Agoge too.

Kings were:

-MILITARY figures: leaders of the army (after a famous dispute in 508 B.C. two kings were not allowed to go out with the same military force).

-POLITICAL figures: presiding officers in the GEROUSIA, the Spartan Senate, kings also had veto power over the doings of the Spartan Assembly (Apella)

-RELIGIOUS figures: priests of special cults of certain gods (Zeus Hellenios and Athena

Hellenia)

GEROUSIA:

The "Old Men": 28 Spartiates over the age of 60 (that is, beyond the age for military service) + the two kings (= 30). The Gerontes (Senators) were elected by the Assembly of Spartiates for life. In fact they controlled much of the public business and decided on what the Assembly could discuss (the

PROBOULEUTIC function); they could also veto actions taken by the Assembly

21

EPHORS:

5 Spartiate "Overseers", elected (?) annually by the Assembly. Any Spartiate could be EPHOR. They had financial, judicial, and administrative powers--even over the Kings and Gerontes! Two Ephors always went with a king on campaign to control arrogance and to protect the interests of the whole State. They manage a kind of teen-Gestapo called the KRYPTEIA ('Secret Service').

ECCLESIA: the Spartiate Assembly, men above 18; could only vote YES or NO, (by making noise); were subject to veto. Could only meet on summons, and only discuss what was submitted to them.

Writer

Herodotus

Time period Views Evidence (Quotes)

Mid 5th century B.C.

Thucydides

Xenophon

Aristotle

4th century B.C. was critical of Sparta

Plutarch

"All the Greeks know what is right, but only the

Spartans do it properly"

Alcman

22

Tyrtaios

Pausanias

23