PREPARING LAWYERS TO ENCOUNTER CORRUPTION – A

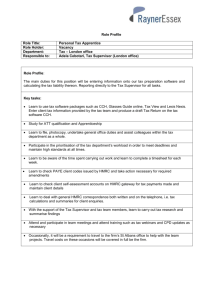

advertisement

PREPARING LAWYERS TO ENCOUNTER CORRUPTION – A CASE STUDY Sally Hughes and Nigel Duncan Work in progress: please do not cite without contacting authors. Whistle-blowers: the OM case Those with inside knowledge of corrupt activities – ‘whistle-blowers’ - fulfil one of the critical roles in disclosure of corruption. Following the 2007 global financial collapse, the forensic processes of regulators and state fraud investigators were important in unpicking the actions of the banks and financial traders. Corruption is intrinsically secret. The ‘victim’ might not be aware of the mischief without knowledgeable input from someone on the inside. For instance, an insider, Herve Falciani, was behind many of the recent revelations about HSBC’s role in protecting and assisting clients worldwide to avoid paying tax. The UK has recognised the need for anti-retaliation measures by incorporating protection for whistle-blowers into the existing employment protection via the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998 (PIDA). However the legislation is difficult to use. Despite more than 15 years of statutory protection for whistle-blowers in the UK, it is regarded as unsatisfactory. The prevalence of confidential settlements means that little is known about the disclosures and the outcomes for the individuals concerned.1 Press reports on employees who have revealed malpractice in the National Health Service have typically found that even when their revelations are justified, their careers in NHS organisations are at an end. A recent statutory public enquiry in the NHS by Robert Francis QC recommended new protections on finding that whistle-blowers had been bullied, smeared and even considered suicide.2 The Law Society called for better protections for whistle-blowers in a Practice Note of 13 June 2013, which stated: ‘Employees may bury concerns if they feel that reporting them would be disloyal to their colleagues, practice or employer which can create an environment that is difficult to manage.’3 The Society urged law firms to take steps to create an open environment and to reassure and support individuals raising concerns. A lawyer blows the whistle on the UK tax authority OM, a tax lawyer, worked in the personal tax litigation team of Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC), the UK taxation authority. In 2011, he used the PIDA advance notification system to write in confidence to the National Audit Office and two Parliamentary Committees, disclosing what he claimed to be an unlawful deal made between Goldman Sachs (an investment bank) and HMRC, reducing the bank’s liability for interest on a failed tax avoidance scheme by £10m.4 For example Krista Bates van Winkelhof’s PIDA-based employment claim against Clyde & Co, a UK law firm, was ultimately settled. Her claim followed her sacking for making allegations concerning the firm’s Tanzanian operation, although a test case for the definition of ‘worker’ under employment law and the PIDA ([2012] EWCA Civ 1207). 2 The Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry February 2015, HC 947. 3 http://www.lawsociety.org.uk/support-services/advice/practice-notes/raising-concerns-andwhistleblowing/. The Law Society is the professional body for solicitors in England & Wales. 1 4 HMRC may exercise discretion in the pursuit of litigation or settlement of disputed tax 1 Subsequently The Guardian newspaper published the story of the deal, triggering an investigation by HMRC into the press leak. Investigators checked on OM’s work computer, email traffic and internet usage. They then examined his belongings, emails, phone calls and his wife’s phone records under the Regulation of Investigatory Power Act 2000 (RIPA – intended for use against terrorists). Despite having no demonstrable link to The Guardian’s story, OM was suspended from work on 8 December 2011. In the meantime, OM’s official disclosure was formally taken up by the Parliamentary Public Accounts Committee (PAC), which investigated the matter5. In public hearings, the PAC questioned David Hartnett, the Head of HMRC, who had made the deal with Goldman Sachs alone and without consultation, apparently in breach of the department’s legal guidelines. Other senior HMRC executives were questioned, and the activities of the government in granting informal and favourable settlements to large companies that had disputed their tax liability gained enormous press coverage. Outcomes 1 The repercussions proliferated, and continue. Subsequently the revelations snowballed as journalists, pressure groups and charities made further investigations. They publicised the extent to which global corporations escape paying the levels of tax that would be justified by their economic activities in the UK. A stream of later PAC hearings broadened the issue and examined in detail the legitimacy of the activities of firms of accountants and tax lawyers who trade in tax avoidance schemes. It was revealed that rich companies could ‘outspend’ HMRC on litigation and consequently negotiate their liability directly with the government. Newspaper articles, campaigns, Members of Parliament and many other trends focussed on unfair differences in tax treatment as between wealthy tax avoiders/withholders and ordinary employees who pay tax at source; and also the differential penalties on tax avoiders and evaders (ie those illegally non-paying) and claimants cheating the welfare benefit system. Public reaction was overwhelmingly adverse. UK Members of Parliament labelled the corporate behaviour immoral, and threatened to pass a new criminal offence of ‘aggressive tax avoidance’. Hartnett’s behaviour was exposed. He was reported to have enjoyed hospitality and cordial relationships with large corporations. He took early retirement after the ‘sweetheart deals’ affair, and was later was reported by The Daily Mail to have obtained a job described as ‘lucrative’ with HSBC.6 liability via statutory guidance, in this case, the Litigation Strategy of 2007. In 2010, the incoming government set out a new tax policy for corporations designed to make the British regime ‘stable’ and offering the most ‘competitive’ environment for global businesses. The Corporate Tax Road Map, November 2010, promised to reduce the general rate of corporation tax while maintaining the tax base by reducing exceptions and allowances. The new policy proposed a more amenable environment to foreign businesses. 5 HM Revenue & Customs 2010-11 Accounts: tax disputes. Sixty-first Report of Session 2010-12. 20 December 2011, HC 1531, http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmpubacc/1531/11110701.htm. 6 Mail Online ‘Former UK tax chief who ‘lied to MPs’ to advise HSBC bank about honesty’ by Rupert Steiner and Becky Barrow, 31 January 2013 2 Outcomes 2 Following OM’s original disclosure and the investigation by the PAC, the Committee issued a critical report in December 2011, concluding that: HMRC’s ‘refusal to disclose taxpayer information prevents proper [Parliamentary] scrutiny of the process for reaching tax settlements with large companies’. The committee could not have confidence in the settlement process. HMRC ‘chose to depart’ from normal governance procedures in several cases allowing ‘Commissioners to sign off on settlements they themselves negotiated’. Compliance failures ‘resulted in … money being lost to the Exchequer’ (Treasury). Those leading HMRC ‘have not taken personal responsibility for serious errors’. HMRC had provoked ‘suspicion that its relationships with large companies are too cosy’. HMRC is not ‘even handed in its treatment of taxpayers’. The resulting National Audit Office report in 20127 proposed to strengthen HMRC internal governance. The NAO proposed to assure itself of HMRC arrangements without external review. HMRC should not only improve governance but also appoint an assurance Commissioner. The Commissioner would approve all settlement proposals over £100m (without having had a role in the individual taxpayer’s affairs) and would review settlements to monitor internal governance. The new arrangements provide ‘greater transparency, scrutiny and accountability’8. A raft of other measures proposed that the litigation and settlement strategy be updated, and that lawyers would always be consulted before finalising settlements in litigation (which had not occurred in the Goldman Sachs case). As to Mba’s complaint, the NAO agreed with the PAC that formal governance procedures should have been upheld. Five cases were externally reviewed by a retired tax judge, Sir Andrew Park, who found: All of five (questionable) settlements were ‘reasonable’. Large tax settlements are complex and there is no clear ‘right’ tax liability. The [HMRC] ‘did not always ensure that the specialist staff involved … understood the reasons for settlement’ (a possible reference to OM). The settlements ‘resolved multiple, long-standing outstanding issues’. Despite being ‘reasonable’, one settlement was not necessarily ‘compatible’ with the departmental Litigation and Settlement Strategy. However, in his view: ‘the concerns raised by whistle-blowers were often based on a partial understanding of the settlement because the details were confidential’.9 In other words, the issues were reduced to the technicalities of internal processes and ultimately to a single issue of whether a narrow provision under s18 (1) of The Commissioners for Revenue and Customs Act 2005 protecting ‘taxpayer confidentiality’ prevented disclosure to Parliament. The introduction of legal concept of ‘reasonableness’ obscures the issue. Outcomes 3 It might have ended there, but for the activities of a campaign group UK Uncut Legal Action, which took the matter of the Goldman Sachs settlement to the High Court in Judicial Review proceedings for a declaration that the deal with HMRC was unlawful. As 7 Settling large tax disputes Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General, HC 188 Session 2012-13, 14 June 2012, http://www.nao.org.uk/report/settling-large-tax-disputes/. 8 NAO report paragraph 21 p 9. 9 NAO report paragraph 10 p 6 3 a result of the proceedings a witness statement by Hartnett was publicly disclosed, admitting that he ‘personally overruled legal advice, the HMRC’s own guidelines and its internal review board, which stated that HMRC was in a position to force Goldman Sachs to pay back the money owed’. The deal struck by Hartnett on 19 November 2010 was rejected 11 days later by HMRC ‘high-risk corporate programme board’ ‘because it had failed to collect interest on the disputed sum’.10 In his evidence to the High Court, Hartnett claimed he had been under pressure from Government ministers because Goldman Sachs threatened to withdraw from a newly agreed Code of Conduct by 15 banks in the event that the missing tax was claimed from the company. A further Guardian report by Rajeev Syal on 7 May 2013 claimed that efforts to discredit OM and to undermine his evidence to the PAC in 2011 was directly supported by a Government minister. In the event, Mr Justice Nicol concluded that HMRC had admitted ‘errors’ and in dismissing the Judicial Review, suggested that the matter was essentially one of policy and ‘maladministration’. He accepted that the erroneous concession had been perpetuated to avoid political embarrassment. The admissions made to the High Court in 2013 by Hartnett give the lie to the NAO report on the specific deals brought into question, and its comments undermining (unnamed) ‘whistle-blowers’. Despite overwhelming public pressure to apply the law fairly to all taxpayers, the UK government has now rejected co-operation with a Europe-wide initiative to implement common tax rules designed to tackle tax avoidance by the world’s biggest multinationals, on the grounds that the UK wishes to remain ‘tax competitive’. Ultimately, OM’s actions were vindicated. The use of RIPA powers against him was only fully revealed in 2014. This means that, at the time of his initial disclosure investigation and suspension (2011), he was unprotected from oppressive use of state power. He no longer works for HMRC. SH and ND July 2015 Contact: n.j.duncan@city.ac.uk _______________________________________________________________________ UK terms Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998 defines valid disclosures. Employment Rights Act 1996 protects the employee from disadvantage as a result of a protected disclosure. A whistle-blower is an employee who makes a good faith disclosure to the authorities in respect of activities at work that are illegal or against the public interest Tax avoidance is the lawful use of exceptions and concessions to reduce liability under general taxation. Tax evasion is the unlawful withholding of tax via non-reporting of taxable income and assets. This is achieved by setting up bogus company structures, secret holdings etc. 10 Initially a summary of this evidence was published The Guardian on 3 May 2013. The report of the resultant decision indorses this account. Indeed, it is cited as the report of UK Uncut Legal Action Ltd v Revenue and Customs Commissioners [2013] EWHC 1283. 4