Mr Brian Little's Surgery original presentation

advertisement

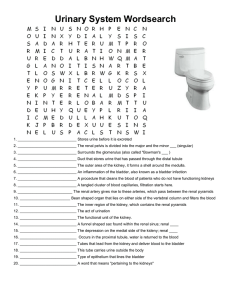

Final Year Students Surgery and Urology Mr Little 1 Objectives • Standard history taking • Physical examination • Diagnosis and investigation • Frequently asked questions 2 FIRST SENTENCE OF ANSWER • “I will take a full history and perform a full physical examination.” • Examiners expect this • Remember to say that you will do a PR, if appropriate. 3 Abdomen • What are the 9 abdominal quadrants called? • How are the lines that divide them defined? 4 Incisions of the abdomen • • • • • • • A: Pfannenstiel B: Appendectomy C: Battles (Pararectal) D: Paramedian E: Midline F: Thoracoabdominal G: Milwaukee (Rooftop) • H: Kochers • I: Tranverse 5 6 Hernias • One of the few parts of final MB where surface anatomy is crucial! Inguinal surface anatomy is used to distinguish inguinal hernias into direct and indirect, and to demonstrate femoral hernias. • Most likely to get inguinal hernias, incisional hernias, femoral hernias, para-umbilical hernias and epigastric hernias. 7 Inguinal surface anatomy • A: Inferior epigastric artery • B: Femoral nerve • C: Femoral artery • D: Femoral vein • E is the most important … • THE PUBIC TUBERCLE 8 Examination of the groin • Usually means either a hernia, a testicular swelling or lymph nodes. • Groin Hernias: • Either an inguinal lump or a scrotal lump you can’t get above. If not clinically obvious, as the patient to stand and/or cough. • Femoral hernias do not usually enter the scrotum. • Try to gently reduce it. • Surface anatomy: If it is below and lateral to the pubic tubercle it’s a femoral hernia. If it’s superior or medial to the pubic tubercle it’s an inguinal hernia. Inguinal is commoner. • Occlusion at the mid-inguinal point (i.e. halfway between the pubic tubercle and the anterior superior iliac spine, i.e. the deep ring) prevents an INDIRECT inguinal hernia from popping out. In the middle-aged male, direct is commoner. 9 Other hernias • • • Incisional: 10% of hernias. Either reduceable or not. Para-umbilical: True umbilical hernias are rare after childhood. Paraumbilical hernias are found in fat middle-aged women. Repaired using Mayo repair Epigastric hernias: Fit young men • Frequent questions: • • • • • • • What is a hernia? What are the three commonest hernias? Who gets most inguinal hernias? Why? What is the commonest female hernia? What are the complications of hernias? What hernias occur ouside the abdomen? What is a Richter’s hernia? 10 Scrotal swellings (i) • CAN I GET ABOVE IT? If you can then it’s coming from the scrotal structures. • Common: Hydrocoeles, Epididymal cysts, spematocoeles. • Uncommon: Tumours • • • • • Examine as for any lump or bump: The 3 ‘S’s: Site, Size, Shape The 3 ‘C’s: Colour, Contour, Consistency The 3 ‘T’s: Tenderness, Tethering, Transillumination The ‘F’er: Fluctulence. 11 Scrotal swellings (ii) • Hydrocoeles: Surround the testis and make it difficult to feel. Transilluminate!!! • Spermatocoeles and epididymal cysts: Smaller, and arise from adnexal structures. Do not obscure testis usually. • Tumours: Stony hard. Arise from testis. • Frequent questions: • • • • • What investigation is appropriate for a newly diagnosed hydrocoele? What is a hydrocoele? What are the risk factors for testicular cancer? What blood tests would you consider for testicle carcinoma? What are the common types of testicle cancer and how are they treated? 12 Stomas (i) • Most likely to be either an iliostomy or an end-colostomy. • Less frequently, loop colostomy or ileal conduit(urinary diversion) • An iliostomy is in the RIF, and protrudes from the abdominal wall. Most commonly fashioned following pan-proctocolectomy in ulcerative colitis, or less frequently for caecal obstruction, polyposis coli or severe Crohns colitis. • An end colostomy is most frequently formed in the LIF, and sits flush with the abdominal wall. Most commonly formed after a Hartmann’s procedure or some rectal excisions. 13 Stomas (ii) • Loop colostomies are uncommon, and tend to be formed in the epigastrium from the transverse colon, or the LIF from the sigmoid colon. It is usually a palliative procedure for carcinomatous obstruction. • Ileal conduit urinary diversions look just like ileostomies, but the bag will contain urine, even if only a little. They are usually formed when the patient has had a cystectomy, often for carcinoma of the bladder. • Frequent questions: • What is this? • Why is it there? 14 Stomas (iii) • Complications: • ILIOSTOMY: • Metabolic: High output, B12 and Folate deficieny, Stones, Anaemia. • Anatomical: Stoma Prolapse and retraction, less frequently stomal stenosis or parastomal herniation • COLOSTOMY: • Mostly Anatomical: – EARLY: Stomal necrosis, ischaemia – LATE: Stomal retraction, prolapse, stenosis, parastomal herniation etc 15 Small bowel obstruction • Intestinal obstruction is characterised by vomiting, abdominal distension, constipation and pain. • In high obstruction, the vomiting tends to occur earlier then the constipation. The reverse is the case for lower GI obstruction. In high obstruction, the distension is minimal. • The commonest causes are: Adhesions (60-80% of cases) and Hernias (10-15%). • Others include: – Extrinsic: Volvulus, Non-GI neoplastic or inflammatory masses – In the wall: Crohn’s disease, Intussussception, Strictures, Atresias. – In the Lumen: Meconium ileus, Gallstones, Foreign body, Faecolith. 16 Small bowel obstruction • Treatment: • Assess for strangulation (Localised tenderness & pain) • If simple (ie no strangulation): – – – – IV fluids, NBM, Analgesia FBP, U&E Monitor urine output NG aspiration for vomiting, if required. • Remember, the rule is that 80% of simple small bowel obstruction will settle with conservative treatment. 17 Large Bowel obstruction • Causes: • Colonic Carcinoma (65%) • Diverticular disease (10%) • Volvulus (5%) • Crohn’s disease • Hernia • Strictures: Ischaemic, anastamotic, inflammatory etc 18 Abdominal Masses • Non-pathological: Gravid Uterus, Faeces in colon, Riedels lobe of liver, kidneys in a thin person. • Standard questiion is to distinguish a kidney from a spleen • RIF: – Sore: Appendix mass/abscess, Crohns mass – Not Sore: Cancer (Caecal, Ovarian, Renal), Fibroids and ovarian cysts, transplanted kidney. • Epigastric – Ca stomach, colon, liver, pancreas • RUQ – Liver, Colon, Right kidney, GB, Adrenal 19 Colorectal Disorders • Colorectal Carcinoma • Important point is that the history is different depending on the side of the colon the carcinoma is: – RIGHT sided carcinomas Present insidiously because the colonic contents are liquid and the colon relatively spacious at this point. Presentation is with the development of anaemia : Fatigue, malaise, weight loss, dark blood in stools. – LEFT sided carcinomas present with the symptoms of narrowing the lumen to more solid matter, Altered bowel habit, alternating constipation and diarrhoea, brighter red PR bleeding. – RECTAL carcinomas also have the symptoms of tenesmus and passage of mucus PR • Colonic carcinomas can also perforate and fistulate 20 Colorectal Disorders • Risk Factors: – Longstanding Ulcerative colitis – Polyposis Coli – Family History • Differential diagnosis: – DIVERTICULAR DISEASE • Any cause of large bowel obstruction • PR Bleeding: Colorectal CA, Diverticular disease, Angiodysplasia, Haemorrhoids, Anal fissure • Investigations of choice: Barium enema and sigmoidoscopy, with CT if carcinoma is confirmed. 21 Colorectal Disorders • TREATMENT: • Surgery • Chemotherapy with 5-Fluorouracil for tumours of stage Dukes C or greater. Some would also give it for Dukes B • Colorectal Carcinoma Complications: Bleeding, Perforation and Fistulation into adjacent organs and obstruction… 22 23 Colorectal Disorders • DIVERTICULAR DISEASE: • The great pretender. Can mimic colorectal carcinoma remarkably. Both cause PR bleeding, can cause intestinal obstruction, can perforate and can fistulate. • Related to low-fibre diet • Chronic symptoms investigated with Ba enema and Sigmoidoscopy. (Aren’t they all) • Often presents acutely with LIF pain and tenderness and rebound. Settles with conservative Rx and Antibiotics usually. • Majority do not require surgery, and are controlled with dietary advice 24 Colorectal Disorders • Inflammatory Bowel disease: Summary table: 25 Colorectal Disorders • Ulcerative colitis • Crohn’s Disease • Palpable masses rare, never fistulates • Occasionally forms inflammatory masses or fistulae • Anorectal sepsis common • Anorectal fissures and infection occur less frequently • Medical Rx successful in 80% • Surgery can be curative • Medical Rx inadequate in 80% • Surgery for complications only 26 Colorectal Disorders • Medical treatment of ulcerative colitis: • 5-ASA derivatives, such as Sulphasalazine or Mesalazine can be used to reduce relapse rate. Delivered either orally, Enemas or suppository form • Prednisolone can be used topically as above, or can be given orally for relapses, up to 60mg per day. It must be weaned off, rather than stopped suddenly. • Anti-diarrhoeals: Codeine, Loperamide. • Endoscopy is used for surveillance • Surgery is used for failure of medical Rx, For Carcinoma, Failure of steroids to induce response in few days, and Toxicity: >8 bloody stools per day, pulse >100, Temp > 38.5 C, Transverse colon dilated beyond 5cm and hypoalbuminaemia. • Often a panproctocolectomy and iliostomy 27 Colorectal Disorders • Crohns disease • Usually not accessable by topical preparations, so generally treated with systemic 5-ASA derivatives or steroids where flare up occurs. • Surgery is often used for the complications: Abscess drainage, resection of fistulas, and removal of strictured segments. • Cannot be cured by surgery. Colonic crohns is a contraindication for continent pouch procedures. 28 29 30 31 Oesophagus and Stomach • More likely to be used in the long case setting, as signs are uncommon, but history is usually detailed. • Haematemesis and melaena. • Use of NSAIDS eg Aspirin, Smoking, Alcohol, Steroids, WARFARIN • Remember to say PR 32 Stomach and Oes. History (i) • This is actually the history of upper GI bleeding, Upper abdominal pain, and upper GI obstruction, with history. • Upper GI Bleeding: – – – – – – – – – – Was it haematemesis or melaena Did one start before the other When did it start How many times has it happened When did it happen last Was it precipitated by anything How much blood was there Coffee-grounds vs fresh blood Did it make them collapse Have they felt tired / easily fatigued / easily short of breath… ANAEMIA! 33 Stomach and Oes. History (ii) • Upper GI obstruction: Oesophagus or Gastric? – At the level of the Oesopagus: Dysphagia, regurgitation of food – At the level of the Stomach: Early satiety, Forceful vomiting, Sucussion splash if you’re lucky! – Both give marked weight loss • History – – – – Drug history: NSAIDS + Aspirin, Warfarin, Steroids. Smoking: Amount per day, and duration. “Have you ever smoked?” Alcohol: As for smoking. Family history • Upper GI pain and differential later 34 Stomach and Oesophagus signs • Signs: THINK: Bleeding, Baccy and Booze. • Bleeding: Pale conjunctivae, pallor. Melaena. (ie more chronic signs) Unlikely to see tachycardia, hypotension etc, as this tends to be quite acute. Remember NSAIDS and Warfarin. Trap for the unwary: Guinness or Iron tablets give you black stools. • Smoking: The most obvious is often nicotine stained fingers! Also remember the signs of COAD: It implies a smoking history. Smoking also significant in the context of cancer: Look for wasting, an LIF mass, Hepatomegaly etc. • Alcohol: This essentially means the signs of chronic liver disease. 35 Stomach and Oesophagus • Oral Questions relating to haematemesis / melaena: • What risk factors did this patient have for Upper GI bleeding? • Why are they on Aspirin / Warfarin / Steroids ? • What investigations will you do AND WHY?: • FBP, Coag, U&E, LFT, G&Csm 4 units, OGD. • If the OGD is negative what investigation will you do (Melaena)? • BARIUM ENEMA • What are the commonest causes of upper GI bleeding: • Gastritis, Duodenitis 36 Stomach and Oesophagus • What are the causes of upper GI bleeding: • • • Oesophagus: Oesophagitis, Oesophageal erosions, Mallory-Weiss tears, Oesphageal varices, Oesophageal carcinoma (rarely) Stomach: Gastritis, Gastric erosions, Gastric ulcers, Gastric carcinoma. Duodenum: Duodenitis, Duodenal Ulcers, Aorto-Enteric fistulas. • How do you treat upper GI bleeding? • Most settle with conservative Rx: IV fluids, NBM, PPI. Can use endoscopy therapeutically for both ulcers and varices. Open resection of ulcer etc rare. • What are oesophageal varices? • What causes them? • What are the other sites of porto-systemic anastamosis? 37 Stomach and Oesophagus • Difficult Question • How would you see this? • What is it? 38 Stomach and Oesophagus • This is a barium swallow. • What is the likely diagnosis? • Difficult question. 39 Stomach and Oesophagus • How would you investigate the patient with a tumour of the stomach or oesophagus on OGD ? • Stage them, using a CT scan of Chest, Abdomen and Pelvis. If resectable then treat surgeically if possible. Radiotherapy is secondline option for oesophagus. Many Gastric and oesophageal tumours are irresectable, so remember to consider palliative care options such as bypass and stenting, laser resection of oesophagus. • What is Barrett’s Oesophagus? • What is it’s significance? • How do you manage it? • What might cause dysphagia? • What drugs are associated with upper GI bleeding? 40 • What kind of X-ray is this? • What does it show? 41 The Liver, biliary system and pancreas • History features: • Jaundice, Upper abdominal pain. • Jaundice: The A to I varies from book to book, but I use: – – – – – – – – – Alcohol Blood tranfusion Contact Drugs (eg Paracetamol) Extrahepatic Family History, Foreign Travel Gallstones Homosexuality Infections ( HBV, EBV, Leptospirosis) 42 The Liver, biliary system and pancreas • Upper Abdominal pain: • Epigastric: – Upper GI: Gastritis, Oesophageal reflux, Peptic Ulcer, Perforation of gastric or duodenal ulcer. – Hepatobiliary: Biliary Colic, Pancreatitis – REMEMBER MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION • Right Hypochondrium – Hepatobiliary: Biliary Colic, Cholecystitis, Cholangitis, Hepatitis, Pancreatitis, Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome. – Upper GI: Peptic Ulcer, Perforation of Ulcer – Other Abdominal: Subphrenic abscess, Appendixitis, Renal Colic – Extra-Abdominal: Right lower lobe pneumonia, Pulmonary embolus. 43 The Liver, biliary system and pancreas • Physical examination often involves looking for the signs of chronic liver disease in the case of jaundice or pancreatitis. Cholecystitis is most frequently abdominal signs only, if uncomplicated. • Surgeons most frequently look after Cholecystitis and Pancreatitis. • Cholecystitis: Remember the 5 F’s! It gives the game away. – Right Upper quadrant pain, aching/colicky, may radiate around to back, often onset at night or in response to fatty foods, may be associated with vomiting. Gallstones in the gallbladder do not cause jaundice unless they move into the common bile duct. – Complications: Jaundice, Pancreatitis. 44 The Liver, biliary system and pancreas • Physical examination usually only shows subcostal tenderness and murphy’s sign. Rarely palpable. 5 F’s • The investigation of cholecystitis is essentially the investigation of upper abdominal pain. • FBP, U&E, AMYLASE, LFT’s, Erect Chest X-Ray, Abdominal film. • Initial Rx: IV Fluids, Nil by mouth. – Cefuroxime for infection. Most add Metronidazole as well. Cholangitis is Jaundice, Fever and Rigors. This is known as Charcot’s triad. • Investigation: Ultrasound of abdomen. OGD if it’s normal. • Treatment: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy or open cholecystectomy. (Don’t use laparoscopic surgery if there are adhesions, or a common bile duct stone) 45 The Liver, biliary system and pancreas • Stones in the common bile duct may produce jaundice and pancreatitis. They are suspected when ultrasound detects a dilated common bile duct, or visualised duct stones. • An ERCP can the be carried out to prove the fact, and the sphincter of oddi divided to allow the stones to pass harmlessly into the duodenum. • They are not removed by a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. At the time of open surgery, an intraoperative cholangiogram is performed to ensure that none are present. If there are, then they are removed with specialised forceps. 46 The Liver, biliary system and pancreas • Pancreatitis: • Presentation is similar to Cholecystitis, but pain is more centralised and is more severe, possibly radiating to the back. Classically the patient lies still with their knees bent. They are generally more unwell. May be shocked, jaundiced. • Physical signs are often absent or very scanty! Consider the signs of chronic liver disease, Cullens sign and Gray-Turner’s sign. Abdominal tenderness to palpation can be poorly localised and hard to define. Pyrexia, Tachycardia. • Initial investigations are the same as for cholecystitis: FBP, U&E, LFT, Amylase, CXR, AXR. Amylase is considered diagnostic for pancreatitis if it is greater than 1000 u/ml. Abdo Xray may show a sentinel loop or loss of psoas shadow. 47 The Liver, biliary system and pancreas • Causes: Gallstones and Alcohol most common. Also GET SMASH’D: Trauma and Surgery, Steroids, Mumps, AI, Scorpions, Hyperlipidaemia and drugs. • Treatment: • • • • • Once diagnosis is established do an arterial blood gas and a serum calcium & glucose. Treat any hypocalcaemia. IV fliuds, nil by mouth. Aim to keep urine output above 30 mls per hour. Consider central line in elderly or CCF patients. Opiate analgesia NG tube Monitor – Hourly urometer, Pulse and BP – 12-hourly arterial bolld gases – Daily FBP, U&E, Calcium and amylase 48 The Liver, biliary system and pancreas You must learn the Ranson criteria, as it is a measure of severity. 0-2: 2% motality, rising to 100% for 7+ • AT PRESENTATION • DURING 1st 48 HOURS • • • • • • • • • • • Age >55 WCC>16 Glucose>11 LDH>350 AST>60 Haematocrit falls >10% Urea rises >10 Serum Ca2+ <2 Base excess <-4 PaO2 <8 kPa Fluid sequestered> 6 litres 49 Jaundice • Most surgeons look after post-hepatic jaundice. This type of jaundice is charcterised by dark urine and pale stools. This is because bilirubin products are not allowed to pass into the GI tract via the biliary tree, but conjugated bilirubin is water soluble and so darkens the urine. • Jaundice is divided into pre-hepatic, hepatic and post-hepatic aetiologies. • Pre-Hepatic: Haemolysis, Heriditary eg Gilbert’s • Hepatic: Cirrhosis, Carcinoma infiltration, Viral, Autoimmune, Paracetamol and other drugs. Halothane is no longer used. • Post-Hepatic (Obstructive): CBD gallstones, Pancreatic carcinoma, Nodes in the porta-Hepatis, Cholangiocarcinoma. Complication of lap chole? 50 Jaundice • The physical signs of chronic liver disease is a gob-standard exam question. Remember to start at the hands and work up! • Hands: Finger clubbing, Leukonechia, Palmar erythema, Dupuytren’s, Asterixis • Skin: Bruising, Spider Naevi, hair loss • Face & Head: Jaundiced sclera. Constructional apraxia, Foetor hepaticus. • Chest: Gynaecomastia • Abdomen: Enlarged liver or spleen, Ascites, Caput Medusae. Remember to ascertain the nature of the liver edge, consistency, tenderness. Bruits etc astronomically rare. • Legs: Peripheral pitting oedema from hypoalbuminaemia. 51 Jaundice • • • • Investigation of the jaundiced patient: FBP, U&E, LFT, Coagulation, Hepatitis Remember Macrocytosis as a sign of alcoholism In obstructive jaundice, the Alkaline Phosphatase will rise out of proportion to the transaminases (These may be slightly up), and the bilirubin is conjugated. • Hepatocellular jaundice is characterised by marked transaminase rise, and a mix of conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin. • Prehepatic Jaundice is unconjugated, (so not present in urine) • Ultrasound: This will tend to separate the Hepatic and Posthepatic jaundices quite nicely also. 52 Jaundice • • • • Questions: What are the causes of Cirrhosis? Alcohol and Hepatitis are the first things to say If pressed: – – – – – Primary Biliary Cirrhosis, Autoimmune hepatitis Haemochromatosis and Wilson’s disease Drugs eg Methotrexate Budd-Chiari syndrome (Hen’s tooth), Cong Cardiac failure. Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency • How would you prepare the jaundiced patient for surgery? • Basically this means correcting any coagulation abn with FFP and/or Vitamin K, and giving perioperative IV fluids to maintain a good urine output (Hepatorenal syndrome more likely in the dehydrated) 53 54 Breast lumps: • • • • Common Breast Lumps… Young Women: Fibroadenoma / Abscess Pregnant / recent sprog: Galactocoele / abscess Middle aged and elderly women: Cancer higher up the differential diagnosis list. • Investigation ***IN THIS ORDER*** 1. Clinical examination 2. Mammogram (USS if premenopausal) 3. FNA aspiration 55 Breast Cancer Treatment • Local treatment: – Usually lumpectomy/partial mastectomy if feasble. Not feasable for central tumours, large tumours or tumours in small breasts etc. • Systemic treatment: – Premenopausal usually chemotherapy – Postmenopausal usually Tamoxifen. (Remember risk of uterine CA) 56 Vascular Cases • Likely Cases: – – – – Aneurysm (AAA) Ischaemic lower limb Ulcer Varicose veins 57 Aneurysm • Mostly Aortic (Within abdo) Next most common is splenic artery aneurysm. Think of Elderly male hypertensive smokers with family history. • Usually need repaired if greater than 5 centimeters in diameter (Risk of bursting increases above this) • Inv: FBP, U&E, ESR (?Inflammatory), CT scan, Chest Xray and ECG • Need emergency CT if painful aneurysm – has it burst? • Now can be repaired with endoluminal stenting in some cases. 58 Chronically Ischaemic lower limb: • Symptoms: – Claudication – • At what distance. • How long does it take to disappear at rest • On the flat or just uphill • Rest pain? • Signs: – – – – – – Absent pulses Colder than other limb Thin, Shiny skin Hair loss on leg Ulcers gangrene • Relevant PMH: – Smoking – Diabetes – Hypertension, Stroke, MI, etc 59 Investigation • Ankle-Brachial pressure index: – Take systolic BP at brachial artery using doppler USS, and compare it to the systolic BP at posterior tibial or dorsalis pedis artery. – Divide the ankle value by the arm value. Should be the same. 0.5=Claudication, 0.3=Rest pain, 0.2= impending gangrenous changes. • Definitive main investigation is arteriography. 60 What’s this? 61 Ulcers • Usually: – Venous: Medial malleolus, Venous excema, varicose veins, skin pigmentation. Surprisingly painless! – Arterial: Black, sloughy, painful. Look for other signs of limb ischaemia. – Neuropathic. Sensory loss. Often diabetics with good pulses – Vasculitic. Sharp, punched out lesions. 62 63 64 65 66 Urology in a nutshell 67 Causes of Haematuria • PRE-RENAL: Coagulation disorder, Sickle-cell, Vasculitis • RENAL: Glomerular disease, Carcinoma, Cystic disease, Trauma, A-V malformations, Emboli • POST RENAL: Stones Infection (Bladder / Prostate / Urethra) Carcinoma (Bladder / Prostate), Traumatic bladder catheterisation, Inflammatory Cystitis 68 Investigation of Haematuria • Painless haematuria is carcinoma until proven otherwise • Initial investigation (For Anything) is full history and examination. • PR! 69 Investigation of Haematuria • Blood Investigations • FBP – Anaemic? White cell count raise indicative of infection?, Enough platelets? • U&E – Are their kidneys working? (Crude test) • Coagulation screen – Haemophilia?, Warfarin? • In Men … PSA • REMEMBER MSSU – Direct microscopy and culture. 70 More Investigation • Urinary Cytology: – Not very sensitive, but an unequivocally positive cytology is quite specific for TCC bladder. • RADIOLOGY: – IVP – Ultrasound – Both are very sensitive and specific, but USS better for small peripheral renal lesions, and IVP better for renal pelvis and ureters. • FLEXIBLE CYSTOSCOPY 71 Bladder Cancer Incidence • • • • Males outnumber females by about 2.7 to 1 Average age at diagnosis is 65 years. 85% confined to bladder at time of presentation. 70% will recur after treatment, and 30% of these will progress • Risk Factors: – SMOKING – Chemical carcinogens – chemical, dye, rubber, petrol, leather and printing industries are at increased risk. Also Cyclophosphamide – Not Coffee 72 Initial diagnosis and treatment • Most are diagnosed using flexible cystoscopy under fresh air, and haematuria investigations. • Non-invasive tests such as PCR analysis, and Matrixmetalloproteinase-9 are yielding some results with high specificity and sensitivity, but remain research tools at present. • IVP – Make sure there are no TCC in the renal pelvis or ureters. For every 50-60 bladder carcinomata, there are 3 Renal pelvis TCC’s and one ureteric TCC • TURBT – Curative for early disease, also provides histology. 73 Staging of TCC bladder CIS Ta T1 T2 T3a T3b mucosa submucosa detrusor muscle Perivesical fat 74 Staging Continued • Also Stage T4a, where the prostate is invaded, and T4b where there is pelvic structure invasion. T3b has a worse prognosis than T3a. • Lymph nodes status, and presence or absence of metastases. • Tumour Grade i.e. degree of preservation of cellular architecture, mitotic figure number etc. • Why bother staging? Treatment is tailored to stage of disease 75 Treatment Options • Ta Single, G1-2, Not recurrent: TURB Multiple, recurrent, or high grade: TURB+Intravesical chemo • T1 G1-2 G3 TURB+Intravesical chemo TURB+BCG • CIS TURB+BCG • T2-T4 Radical Cystectomy Radiotherapy • N+ or M+ ?Chemotherapy - MVAC 76 Surgery and Radiotherapy • TURBT • Radical cystectomy: Major intra-abdominal procedure. Can divert urine either to an ileal conduit, or make a new bladder from bowel or colon. Incidental lymph node mets found in 2035% 5 year survival a bit better than DXT – 65% for T2-T4 disease. • Pelvic Radiotherapy: 20-40% 5 year survival, but 15% get local complications, e.g. radiation cystitis or proctitis. 77 Chemotherapy • Intravesical – Mitomycin response rate 40-50%. Consider single dose intravesically post surgery rather than 6 week course. Occasionally produces chemical cystitis. – BCG decreases recurrence from 80 to 40%, and decreases progression from 35% to 7%. Cystitis in 90% and haematuria in 33% • Systemic – MVAC (Methotrexate, Vinblastine, doxorubicin, cisplatin) 13-35% response rate, but median survival rate is only one year – Difficult to convince oncologists to give! 78 The bottom line • Five-year survival : • Stage • • • • • Ta T1 T2 T3 T4 94% 69% 40% 31% 0 • Worse with increasing grade, and increased grade and stage associated with increased risk of metastatic disease. 79 Why Is a Spleen Not a Kidney? • Very common exam question! • • • • • • Kidneys do not move with respiration Kidneys enlarge up & down, not to the RIF Kidneys are resonant to percussion Kidneys are ballottable Kidneys do not have a notch You can get above a kidney 80 What Causes Big Kidneys? Unilateral: • Carcinoma – Renal cell, transitional cell in adults – Nephroblastoma (wilm’s tumour) in kids Bilateral • Polycystic kidneys • Bilateral hydronephrosis • Amyloid … hen’s tooth • Hydronephrosis – Tend to be chronic e.g. PUJ obstruction, reflux • Simple cysts • Compensatory hypertrophy 81 Renal Cell Carcinoma • Synonyms: hypernephroma, clear-cell carcinoma. • Incidence: 2-3% of all adult cancers. • Renal cell carcinoma is roughly 85% of all renal tumours, the remainder being things like transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis, and renal sarcoma. • Age peak of 40-70 years old. • Males outnumber females 2:1 • Risk factors: – Smoking. – Others: Von-Hippel Lindau syndrome, horseshoe kidneys, adult polycystic kidney disease, acquired renal cystic disease. 82 RCC Aetiology and Presentation • Arises from the cells of the proximal convoluted tubule. • Presentation classically: – Haematuria – Flank pain – Loin mass Only true in 15% • 50% diagnosed as incidental findings in 1995, during USS or CT for other problem. • 30% present with metastatic symptoms: – Bone pain, dyspnoea, cough, etc. – (Often to liver, lungs, bones, brain and adrenal glands) 83 Why Physicians Like It Paraneoplastic syndromes • Erythrocytosis: • Hypercalcaemia: • Hypertension: • Deranged LFT’s: • Sundry others: (3-10%) from increased erythropoetin production. (3-13%) either from a PTH-like substance, or from osteolytic hypercalcaemia. (Up to 40%) Stauffer’s syndrome, from hepatotoxic tumour products. Rarely produces ACTH (Cushing’s syndrome), enteroglucagon (protein enteropathy), prolactin (galactorrhoea), insulin (hypoglycaemia) and gonadotropins. 84 Diagnosis and Staging • Initial diagnosis: – FBP, U&E, LFT. – IVP and ultrasound. – MSSU: direct microscopy. • Staging: – CT scan chest, abdomen and pelvis +/- head. – Isotope bone scan. • Rarely: – Renal arteriography. – Biopsy. – Cavogram. 85 Pathological Staging (1) • May be different than your textbooks. The TNM people revised this in 1997, and it may not be in older versions. • Tumour: – T1 <7cm, intra renal – T2 >7 cm, intra renal – T3 tumour extends into major veins or perinephric tissues, but not beyond gerota’s fascia – T4 tumour beyond gerota’s fascia • Lymph nodes – N0 no nodes – N1 single lymph-node < 2cm – N2 single lymph node 2-5cm or multiple nodes <5cm – N3 any nodes >5cm • Metastases: – M0 no metastases – M1 distant metastases (often to liver, lungs, bones, brain and adrenal glands) 86 Pathological Staging (2) • And after all that: Stage 1: Stage 2: Stage 3: Stage 4: T1 T2 T1-2 T3 T4 Any T Any T N0 N0 N1 n0-1 any N N2-3 any N M0 M0 M0 m0 M0 M0 M1 87 Treatment • Get rid of the primary tumour – Radical nephrectomy • Open or laparoscopic? Laparoscopic has faster patient recovery, but is timeconsuming in theatre. – Partial nephrectomy for small polar tumours, less than 4 cm diameter. – Embolisation. – Consider small tumours below 2cm in unfit patients for watching? 88 Chemotherapy? • Renal cell carcinoma has a track record of being unresponsive to chemotherapy. • Immunotherapy: – Only works for clear cell type, the largest pathological group of RCC. – Only used if lymph-node metastases, or metastases to solid organs. Cerebral metastases are a contra-indication. – – – – – • Combination regimens based on cytokines Interleukin-2 19% response rate alone Interferon-α 11% response rate Together 25-30% response Combinations of interleukin-2, interferon-α and 5-fluorouracil have produced response rates of 39% in one series. The main problem with immunotherapy is that it has a lot of side effects, such as fever, hypotension, tachycardia, oliguria. You can end up in ICU from it, but this is rare. 89 The Bottom Line: • Responses to immunotherapy tend to be short-lived, i.e. Months. • Relapsers tend not to respond to more immunotherapy. 5-year survival: • • • • T1 T2 & t3a T3b T4 88-100% 60% 15-20% 0-20% Tumor stage T3 can be subdivided into 2 groups: T3a can invade the adrenal or perinephric tissue, but remains within gerota’s fascia, and T3b invades the Renal vein or IVC. 90 Other Renal Tumours (Adult) … Uncommon • Sarcoma: females outnumber males by 2:1. Surgery only effective therapy. Prognosis poor. • Transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis. • Haematologic tumours (lymphoma deposits etc) • Metastatic tumours: (In order of frequency) – Lung – Breast – Stomach • Non-tumours that masquerade as such: – Oncocytoma – Angiomyolipoma – Others: leiomyomas, haemangiomas 91 Symptoms of BOO • “Irritative” – Frequency, Urgency, Nocturia > 2 times per night • “Obstructive” – Hesitancy, Poor flow, Terminal dribbling. • Others: – Recurrent urinary tract infections as a consequence of impaired bladder emptying – Haematuria rarely. • Can be scored using IPSS system 92 Causes of impaired bladder emptying(i) • Detrusor failure, i.e. “weak bladder” – Think of the bladder with it’s nerve supply. Any disorder of nervous control may impair emptying. For example: • Spine: Injuries, Disc prolapse, Spina bifida. • Nerves: Diabetes, Multiple sclerosis. • Bladder: Myogenic failure. 93 Causes of impaired bladder emptying(ii) • Outlet Obstruction i.e. “blocked bladder” • Mostly a male phenomenon. Can be any cause from bladder neck to outside world. For example: – Prostatic enlargement – Bladder neck hypertrophy (Often post TURP) – Urethral strictures (Often post instrumentations, also STD) – Meatal stenosis (As for strictures, also after botched circumcisions and a condition called Balanitis Xerotica Obliterans) – In male infants: Posterior urethral valves 94 Investigation of BOO symptoms • History and examination • Don’t forget to do PR!!! • FBP, U&E, Glucose, MSSU • Prostate specific antigen (PSA) – Currently best blood-test for separating benign prostatic disease from prostate cancer. It rises in cases of cancer. It can also rise with urinary tract infections, and following episodes of urinary retention or urinary instrumentation. Also slowly rises with age. • Ultrasound of bladder (Is it emptying? If creatinine abnormal then also ultrasound kidneys, looking for obstructive uropathy) • Urinary flow rate 95 Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy • PSA should be within normal range or biopsies have shown no carcinoma. • Usually treated medically, unless there is an absolute indication for surgery: – – – – – Refractory retention Recurrent UTI Bladder stones Obstructive uropathy Recurrent or persistent haematuria • Symptom control is only a relative indication! 96 Obstructive Uropathy • Basically this is renal impairment caused by chronic bladder outlet obstruction. • It produces a detectable rise in creatinine, and eventually can be seen on ultrasound as thinning of the renal cortex. • It means that the best treatment is operative relief of obstruction. 97 Acute Urinary Retention • This is the end-stage of urinary outflow obstruction. • Preceding outlet symptoms, with the ‘straw that breaks the camel’s back’ often being an intercurrent UTI, an episode of constipation, immobility or postoperatively. • Provided there is no obstructive uropathy, can be started on medical treatment and catheter removed after a day or two. 98 Medical management of prostatic obstruction • Two broad groups of drugs: – Alpha-blockers: These produce smooth muscle relaxation within the prostate, and so widen the outflow tract. Older generation drugs have been associated with postural hypotension, but newer drugs such Tamsulosin have minimised this. – 5-alpha reductase inhibitors: blocks testosterone metabolism to produce a 25% decrease in prostate volume. Better for large ‘fleshy’ glands. 5% of patients get hot flushes, and can also cause gynaecomastia. Finasteride is the only drug in this group. 99 Surgical management of prostatic obstruction • A variety of operations has been tried, such as prostatic microwave, cryoablation, and transurethral incision of the prostate. • However, none has replaced TURP (Trans-urethral resection of prostate), which remains the gold standard. • TURP is not always successful, however. The most common early complication is failure to void after catheter removal (6%). There is also a small risk of incontinence from external sphincter damage. • And finally: After TURP erectile failure may be produced, and ALWAYS retrograde ejaculation is caused. 100 Prostatic carcinoma • 4th commonest cancer death, after lung,colon and breast. • Rare before age 40, peak incidence in 70’s. • 70% arise in the peripheral zone of the prostate. • Most often found on PR or PSA testing • 40% have metastases at the time of diagnosis. 101 Prostate Carcinoma • Suspected on digital rectal examination or a raised PSA. • Diagnosed by BIOPSY, or found at TURP. 102 Further investigation • Is the prostate cancer 1. 2. 3. • Metastatic ( Only treatable with Hormones) Locally advanced (Hormones or radiotherapy) Confined to the prostate (Hormones, Radio or Surgery) Staging of prostate cancer requires an isotope bone scan. In patients under 75 years, where surgery or radiotherapy are being considered, a CT scan is also required. 103 Staging (TNM) • T1a: Tumor in <5% TURP specimen, incidental finding. T1b: Tumor in >5% TURP specimen, incidental finding. T1c: Tumor non-palpable, diagnosed on biopsy. • • • • • T2a: Palpable, half a lobe or less T2b: Palpable, half to all of one lobe T2c: Palpable, involves both lobes. • N0: No lymph node metastases N1: Single node metastasis, below 2cm in size N2: Mets to a single node between 2 and 5 cm, or multiple nodes less than 5cm. N3: Lymph node metastasis > 5cm • • • T3a: Unilateral extracapsular extension T3b: Bilateral extracapsular extension T3c: Tumor invades seminal vesicles • • M0: No Metastases. M1: Metastases • T4a: Invades bladder neck, external sphincter or rectum T4b: Invades levator muscles, or is fixed to pelvic side-wall. • • • • 104 Treatment - Surgery • For prostate cancer without metastases, which is confined to the prostate, PSA is below 15, and age below 70, consider RADICAL PROSTATECTOMY. • Major intra-abdominal procedure, with significant morbidity. Almost inevitably produces total erectile failure, and a variable degree of incontinence. Incontinence tends to improve / resolve with pelvic floor exercises. • 5 year disease-free survival for T2 cancer with surgery is 80% 105 Treatment - Radiotherapy • Consider in males with disease that has spread locally outside the prostate below age 75. Also for prostate confined disease in men below 70 years, unfit for surgery, and without metastases. • Can be given as external beam or brachytherapy (implanted radioactive particles within the prostate) • Complications: – – – – Bladder: Frequency, Urgency, Haematuria. Bowel: Diarrhoea, Tenesmus, PR bleeding. Skin: Rash Rarely, fistulas may be caused. • 5 year disease free survival for T2 disease is 70% (Slightly lower than for surgery) 106 Treatment - Hormones • Prostate carcinoma is dependant on testosterone to survive. The medication used attempts to block testosterone synthesis. They are used in cases of metastatic disease or age >75 years or unfitness for either surgery or radiotherapy for localised disease. – Gonadotropin analogues: Goserelin, Leuprolin. Often given as monthly or 3-monthly injections. Initially produce a tumour flare, so can only be started after several days of an anti-androgen. – Anti-androgens: Flutamide, Bicalutamide, Cyproterone acetate. Tablet form once daily. – Both of these medication groups produce significant side-effects: most often hot-flushes, erectile failure, loss of libido, and gynaecomastia. • Treatment can be combined, using both a GNRH analogue and an antiandrogen. On average a 2-year response is achieved until the development of ‘Hormone-resistance’. Alterative drugs for advanced disease include Oestrogens and Estramustine. 107 Ooh, Controversy! • In elderly men, i.e. age greater than 75, there is an argument for not investigating an asymptomatically raised PSA. • The reason is that at this age, there is a significant chance they will die of something else, and the only treatment would be Hormonal manipulation anyway. Some argue that treatment should be witheld until the development of outflow symptoms or metastatic discomfort, and then instituted. • The idea is to avoid needlessly treating and worrying elderly men 108 Urinary tract Calculi • Ureteric Calculi: Most pass without difficulty, especially if below 5mm in diameter. Above 7mm they are unlikely to pass. • If calculi are not passing, or if they are causing blockage of the kidney as shown on IVP, then they can be removed endoscopically using a Ureteroscope and either Laser or EHL or basket extraction. If there’s a lot of ureteric swelling then a stent can be left in for 4-6 weeks and then removed. • Ureteric calculi can be a symptom of a raised serum Calcium, so remember to check it! 109 Urinary tract Calculi • Renal Calculi: • Generally present either as a cause of recurring infections or a cause of pain in the loin or flank. If large enough, they can seriously compromise renal function. This can be detected using a DMSA scan. • In a functioning kidney, stones up to about 2cm can be fragmented with ESWL sessions, which may be multiple. Larger stones or multiple stones may be dealt with operatively using PCNL, where a tube is inserted though the flank into the renal pelvis, and the stones surgically fragmented and removed. Very large stones may need to be removed using an open pyelolithotomy. • If the kidney is non-functioning then it can be removed. 110 Okay brain, it’s all up to you. (Homer J Simpson) 111