FILE - Ema Sullivan

advertisement

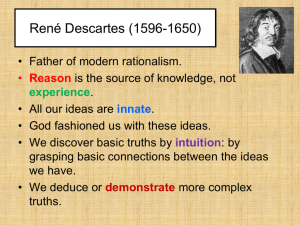

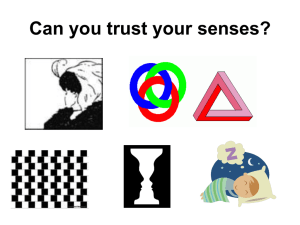

Knowledge and Reality Scepticism Lecture one: The Sceptical Argument Ema Sullivan-Bissett ema.sullivan-bissett@york.ac.uk www.emasullivan-bissett.com Feedback and Advice hour: Thursdays, 11:30, office A/101 (weeks 2–6) WARNING: Lecture Recording • • Pathway lectures recorded. Available on the VLE (restricted access). • Reasons to attend lectures: ~ ∀x ((Lx & Rx) ⊃ ~Asx) 1. See your course mates. 2. Hear the lecture! 3. Experience surprise break dancing routine (look up the Paradox of the Surprise Examination for insight as to when this might occur). Knowledge and Reality • BLOCK ONE – SCEPTICISM • BLOCK TWO – STUFF • BLOCK THREE – SCIENCE • BLOCK FOUR – GOD Course Structure • Topic one: The Sceptical Challenge • Topic two: The Commonsense Response • Topic three: Contextualism • Topic four: Semantic Externalism Course Delivery Four lectures (one per topic) • Tuesday 7th October, 15:00 YOU ARE HERE – The Sceptical Challenge • Thursday 9th October, 10:00 – The Commonsense Response • Tuesday 21st October: 15:00 – Contextualism • Thursday 23rd October: 10:00 – Semantic Externalism Two seminars (one per two topics) • Week two/three: – The Sceptical Challenge and The Commonsense Response • Week four/five: – Contextualism and Semantic Externalism Course Assessment • One 1500 word essay due: By noon on 10th November (Monday week seven). • Essay questions now on the VLE and on my personal website. The Sceptical Challenge The First Meditation • Essential reading for the first seminar! • (Read all six meditations.) “You’re a lesser human being if you don’t read it all” – Tom Stoneham, September 2013. What can be called into doubt ‘I realized that it was necessary, once in the course of my life, to demolish everything completely and start again right from the foundations if I wanted to establish anything at all in the sciences that was stable and likely to last. […] I am here quite alone, and at last I will devote myself sincerely and without reservation to the general demolition of my opinions’ (Descartes 1641/1996: 12) What can be called into doubt • Doubt is developed in stages—we don’t lose the whole web of beliefs at once. Rather: ‘at each stage some beliefs are called into question, but others survive, pending the deployment of more powerful sceptical considerations’ (Williams 1998: 37). The (un)Reliability of the Senses ‘Whatever I have up till now accepted as most true I have acquired either from the senses or through the senses. But from time to time I have found that the senses deceive, and it is prudent never to trust completely those who have deceived us even once’ (Descartes 1641/1996: 12). • E.g., size of distant objects. • So Descartes ‘cannot trust his senses without qualification, because they have often deceived him about objects that are barely perceptible or very far away’ (Williams 1998: 37). A Limiting Conclusion ‘[A]lthough the senses occasionally deceive us with respect to objects which are very small or in the distance, there are many other beliefs about which doubt is quite impossible, even though they are derived from the senses’ (Descartes 1641/1996 12–13). The Best Case for Knowledge from the Senses • We need to find a case in which we think the senses do give us knowledge of the world around us: ‘I am here, sitting by the fire, wearing a winter dressing-gown, holding this piece of paper in my hands, and so on. Again, how could it be denied that these hands or this whole body are mine?’ (Descartes 1641/1996: 13). • This case is ‘representative of the best position any of us can ever be in for knowing things about the world around us on the basis of the senses’ (Stroud 1984b: 10). • Whatever conclusions Descartes is able to draw from this can support a general conclusion. The Possibility of Dreaming • Descartes is sitting by the fire, in his gown, holding a piece of paper: surely this is something he knows? ‘How often, asleep at night, am I convinced of just such familiar events – that I am here in my dressing-gown, sitting by the fire – when in fact I am lying undressed in bed! Yet at the moment my eyes are certainly wide awake when I look at this piece of paper; I shake my head and it is not asleep; as I stretch out and feel my hand I do so deliberately, and I know what I am doing. All this would not happen with such distinctness to someone asleep. Indeed! As if I did not remember other occasions when I have been tricked by exactly similar thoughts while asleep! As I think about this more carefully, I see plainly that there are never any sure signs by means of which being awake can be distinguished from being asleep. The result is that I begin to feel dazed, and this very feeling only reinforces the notion that I may be asleep’ (Descartes 1641/1996: 13). The Possibility of Dreaming • The possibility of dreaming gives rise to a problem: there is no way of telling whether we are dreaming or not. Dreams: ‘do not correspond in any reliable way to ongoing events in our surroundings and so do not yield knowledge of them. But there is no waking experience that could not, in principle, be faithfully mimicked by a suitably vivid dream. So how do I know that I am not dreaming right now? How do I know that I am not dreaming all the time? I can pinch myself, but maybe that is just part of the dream. In fact, it seems that any test I could propose might just be part of the dream’ (Williams 1996: 69–70). Another Limiting Conclusion • Even the possibility of dreaming is not one which ‘pushes scepticism to the limit’ (Williams 2001: 70). • It might be the case that I’m dreaming that I’m sitting by the fire, in my winter dressing gown, holding this piece of paper, but the imagination can only do so much: ‘Even in our wildest dreams, the imagination only produces unfamiliar combinations of familiar things’ (Williams 2001: 70). Another Limiting Conclusion ‘Suppose then that I am dreaming, and that these particulars – that my eyes are open, that I am moving my head and stretching out my hands – are not true. Perhaps, indeed, I do not even have such hands or such a body at all. Nonetheless, it must surely be admitted that the visions which come in sleep are like paintings, which must have been fashioned in the likeness of things that are real and exist. For even when painters try to create sirens and satyrs with the most extraordinary bodies, they cannot give them natures which are new in all respects; they simply jumble up the limbs of different animals. Or if perhaps they manage to think up something so new that nothing remotely similar has ever been seen before – something which is therefore completely fictitious and unreal – at least the colours used in the composition must be real. By similar reasoning, although these general kinds of things – eyes, head, hands and so on – could be imaginary, it must at least be admitted that certain other even simpler and more universal things are real. These are as it were the real colours from which we form all the images of things, whether true or false, that occur in our thought’ (Descartes 1641/1996: 13–14) . The Possibility of an Evil Demon ‘I will suppose […] some malicious demon of the utmost power and cunning has employed all his energies in order to deceive me. I shall think that the sky, the air, the earth, colours, shapes, sounds and all external things are merely the delusions of dreams which he has devised to ensnare my judgement. I shall consider myself as not having hands or eyes, or flesh, or blood or senses, but as falsely believing that I have all these things’ (Descartes 1641/1996: 15). Radical Scepticism Reached! • This move now has taken away even knowledge of bare particulars which might inform our dreams. • So now, ‘[n]ot merely is the world nothing like the way I experience it to be, perhaps there is no ‘external world’ at all, or at least no world of physical objects’ (Williams 2001: 70). ‘This device provides Descartes with a thought-experiment that can be generally applied: if there were an indefinitely powerful agency who was misleading me to the greatest conceivable extent, would this kind of belief or experience be correct? Thinking in these terms, Descartes is led to identify whole tracts of his ordinary experience he may lay aside, so that he suspends belief in the whole of the material world, including his own body’ (Williams 1996: xiii). Taking Stock At the end of the first Meditation… • Descartes cast doubt on the reliability of the senses, so when we think about the size of objects in the distant, or when we think about optical illusions, our senses can’t be trusted. • But, these cases won’t get us to radical scepticism, because these cases do not have us in a good position to use our senses to gain knowledge. • Descartes moves to the best position: cue deployment of sceptical scenario number two! He could be dreaming! • This won’t get us to radical scepticism either – dreamers are like painters. • Cue deployment of sceptical scenario three! An evil demon has made it his work to deceive me – about everything! Descartes’ Final Thought ‘I shall stubbornly and firmly persist in this meditation; and, even if it is not in my power to know any truth, I shall at least do what is in my power, that is, resolutely guard against assenting to any falsehoods, so that the deceiver, however powerful and cunning he may be, will be unable to impose on me in the slightest degree. But this is an arduous undertaking, and a kind of laziness brings me back to normal life. I am like a prisoner who is enjoying an imaginary freedom while asleep; as he begins to suspect that he is asleep, he dreads being woken up, and goes along with the pleasant illusion as long as he can. In the same way, I happily slide back into my old opinions and dread being shaken out of them, for fear that my peaceful sleep may be followed by hard labour when I wake, and that I shall have to toil not in the light, but amid the inextricable darkness of the problems I have now raised’ (Descartes 1641/1996: 15). Elgin’s First Thought ‘Descartes’ demon is an irritatingly resilient little imp. Whenever a clever epistemologist threatens to disarm him, he feints, parries and reappears seemingly unscathed. I have not devised a way to permanently squelch him. I doubt that it can be done’ (Elgin 2010: 1). BREAK Descartes was not a Cartesian Sceptic (no…really!) • ‘[T]he scepticism of the Meditations is pre-emptive. Descartes claimed that he has taken the doubts of the sceptics farther than the sceptics had taken them, and had been able to come out the other side’ (Williams 1996: xv). • Referring to the meditations, Descartes wrote: ‘Nothing conduces more to the obtaining of a secure knowledge of reality than a previous accustoming of ourselves to entertain doubts especially about corporeal things; and although I had long ago seen several books written by the Academics about this subject and felt some disgust in warming over again that old cabbage, I could not […] refuse to allot to this subject one whole Meditation’ (II Rep., HR II 31, cited in Burnyeat 1982: 33). Fast forward 400 years… The Sceptical Paradox • Pritchard: take ‘SH’ to refer to a sceptical hypothesis – we can use Descartes’ evil demon. Take ‘O’ to be an ordinary proposition which we take ourselves to know (and which therefore, entails the falsity of the sceptical hypothesis). The three incompatible propositions can be stated thus: 1. I know O. 2. I do not know not-SH. 3. If I do not know not-SH, then I do not know O. The Sceptical Paradox 1*. I know I’m stood in front of one hundred undergraduates delivering a lecture. 2*. I do not know that I am not being deceived by an evil demon. 3*. If I do not that I am not being deceived by an evil demon, then I do not know that I’m stood in front of one hundred undergraduates delivering a lecture. ‘We are thus in a bind’ ‘If one knows anything, then one ought to be able to know the ordinary proposition at issue in line (1). Furthermore, as line (2) makes explicit, the very sort of propositions which one seems unable, in principle, to know are the denials of radical skeptical hypotheses, since these hypotheses concern scenarios which are phenomenologically indistinguishable from everyday life. Finally, it seems relatively uncontroversial to argue with line (3), that in order to know these ordinary propositions one must be able to know that the relevant skeptical hypotheses are false, since they seem to constitute defeaters for our everyday knowledge. One cannot consistently endorse all three of these claims, however. We are thus in a bind’ (Pritchard 2002: 127). The Sceptic’s Way Out • Deny proposition (1) and then the paradox goes away. The sceptic will argue as follows: (S1) I do not know not-SH. (S2) If I do not know not-SH, then I do not know O. (SC) I do not know O. (Pritchard 2002: 127) The Sceptic’s Way Out (S1*) I do not know that I am not being deceived by an evil demon. (S2*) If I do not know that I am not being deceived by an evil demon, then I do not know that I am delivering a lecture to one hundred undergraduates. (SC*) Therefore I do not know that I am delivering a lecture to one hundred undergraduates. Brain in a Vat (BiV) Argument • Our sceptical scenario: ‘Suppose that aliens, whose technological capabilities are far in advance of our own, capture me while I am asleep, drug me, and remove my brain, which they keep alive in a vat of nutrients. They then implant micro-electrodes in all the afferent nerve pathways to my brain. These electrodes are controlled by a supercomputer so as to exactly mimic the pattern of nerve-firing that would be produced if I were sitting at a desk, looking at a computer screen, and amusing myself with the thought of being abducted by aliens and made into a brain in a vat’ (Williams 2001: 70). Brain in a Vat (BiV) Argument (S1) I do not know that I am not a brain in a vat. (S2) If I do not know that I am not a brain in a vat then I do not know that I have two hands. (SC) I do not know that I have two hands. (S1) I do not know that I am not a brain in a vat. • The way the sceptic has the set up the scenario, it is going to come out as true that I do not know that I am not a brain in a vat, and this is because the sceptic has helped herself to phenomenal indistinguishability. Phenomenal Indistinguishability • When philosophers talk about the phenomenal character of a state, they are talking about how it feels to be in the state. • If we say two states are phenomenally indistinguishable, we’re saying that the way it feels to be in one state, is indistinguishable from the way it feels to be in the other state. Phenomenal Indistinguishability and the BiV scenario • Now if I were a brain in a vat, my experience of delivering a lecture to one hundred undergraduates would be, ex hypothesi, phenomenally indistinguishable from being a brain in a vat, having my brain manipulated such that I merely believed that I was delivering a lecture to one hundred undergraduates. • So the reason we cannot know the denial of sceptical hypotheses, is because ‘these hypotheses concern scenarios which are phenomenologically indistinguishable from everyday life’ (Pritchard 2002: 127). • Sceptical hypotheses show that ‘there are endlessly many ways that the world might be, even though my experience of it remains unchanged’ (Williams 2001: 71). Phenomenal Indistinguishability and the BiV scenario • My experience cannot point either way, but it is all I have to go on: ‘I have no magical faculty for intuiting how things are in my surroundings. My only basis for my beliefs about the world is how the world presents itself to me in experience. It looks as though my beliefs about the world, however unshakeable, are oddly groundless: mere beliefs rather than genuine knowledge’ (Williams 2001: 71). ‘[I]f you are a BIV, you are reduced to a mere brain which is stimulated in such a way that the delusion of a normal life results. So the experiences you have as a BIV and the experiences you have as a normal person are perfectly alike, indistinguishable, so to speak, "from the inside." It doesn't look to you as though you are a BIV. After all, you can see that you have a body, and you can freely move about in your environment. The problem is that it looks that way to a BIV, too. As a result, the evidence you have as a normal person and the evidence you have as a BIV do not relevantly differ. Consequently, your evidence can't settle the question of whether or not you are a BIV. Based on this thought, the skeptics claim you don't know that you are not a BIV. That's the first step of the case for scepticism’ (Steup 2005). (S2) If I do not know that I am not a brain in a vat then I do not know that I have two hands. • Sceptical hypotheses ‘constitute defeaters for our everyday knowledge’ (Pritchard 2002: 127). • If I am a brain in a vat, it follows that I don’t have hands. My experiences as a brain in a vat would be indistinguishable from the experiences I would have if I were the person I thought I was. So I am unable to distinguish between being a brain in a vat and not being a brain in a vat. But: ‘If you can't distinguish between being and not being a BIV, you can't distinguish either between having and not having hands. But if you can't distinguish between having and not having hands, surely you don't know that you have hands’ (Steup 2005). Premises look true, valid and sound argument for scepticism… So now what? So What? • Fine– you win. I don’t know anything. But so what? • Ex hypothesi, even if I am in one of your sceptical scenarios, my experiences are going to be the same. • ‘So far as I’m concerned, my virtual reality is as good as the real thing’ (Williams 2001: 79). • Let me be happy in my ignorance, because in terms of what I experience, it just doesn’t matter. We Can’t Take this Seriously • We are unable to take sceptical worries seriously, so we shouldn’t worry about meeting the sceptic’s challenge. • No sensible person could take it seriously, so it’s just ‘frivolous or perverse to concentrate on a view that is not even a conceivable candidate in the competition for the true or best theory as to how things are’ (Stroud 1984a: 545). ‘That kind of reaction seems to me to rest on a philosophical misconception’ (Stroud 1984a: 545). The Philosophical Significance of the Sceptic’s Challenge ‘There are often what look like good arguments for surprising or outrageous conclusions. Taking the paradoxical reasonings seriously and re-examining the assumptions they rest on can be important and fruitful when there is no question at all of our ever contemplating adopting a "theory" or doctrine embodying the absurd conclusion’ (Stroud 1984a: 545). ‘The point of philosophy is to start with something so simple as not to seem worth stating, and to end with something so paradoxical that no one will believe it’ (Russell 1918: 193). Our Task • Stroud: what the sceptic’s challenge forces us to do is to work out how it is that sense-perception gives us knowledge of the world. ‘Given the events or experiences or whatever they might be that serve as the sensory "basis" of our knowledge, it does not follow that something we believe about the world around us is true. The problem is then to explain how we nevertheless know that what we do believe about the world around us is in fact true. Given the apparent "obstacle," how is our knowledge possible?’ (Stroud 1984a: 549). Our Task • Several possibilities of the way the world is are compatible with our experience of the world, so how do we know that ‘one of those possibilities involving the truth of our beliefs about the world does obtain and the others do not’? (Stroud 1984a: 549). ‘The Cartesian problem of our knowledge of the external world therefore becomes: how can we know anything about the world around us on the basis of the senses if the senses give us only what Descartes says they give us? What we gain through the senses is on Descartes’s view only information that is compatible with our dreaming things about the world around us and not knowing anything about that world. How then can we know anything about the world by means of the senses? The Cartesian argument presents a challenge to our knowledge, and the problem of our knowledge of the external world is to show how that challenge can be met’ (Stroud 1984b: 12-13). ‘Despite the enormous quantity of ink spilled over it, there is still no agreed solution’ (Williams 2001: 69). Next: The Commonsense Response Contextualism Semantic Externalism Prepare for the Seminars! References Burnyeat, M. F 1982: ‘Idealism and Greek Philosophy: What Descartes Saw and Berkeley Missed’. Philosophical Review . Vol. 91, pp. 3–40. Descartes, Rene 1641/1996: Meditations on First Philosophy (trans. J. Cottingham). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Elgin, Catherine 2010: ‘Skepticism Aside’. In Campbell, J., O’Rourke, M., and Silverstein, H. (eds.) Knowledge and Skepticism. Cambridge: MIT Press. Pritchard, Duncan 2002: ‘Recent Work on Radical Skepticism’, American Philosophical Quarterly . Vol. 39, pp. 215–57. Russell, Betrand 1918: ‘The Philosophy of Logical Atomism’. In his Logic and Knowledge, ed. R.C. Marsh. London: Allen & Unwin, 1956., pp. 177–281. Steup, Matthias 2005: ‘Epistemology’, Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, online at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epistemology Stroud, Barry 1984a: ‘Scepticism and the Possibility of Knowledge’, The Journal of Philosophy. Vol. 81, pp. 545–551. Stroud, Barry 1984b: ‘The Problem of the External World’ in his The Significance of Philosophical Scepticism. New York : Oxford University Press Williams, Michael 1998 ‘Descartes & the Metaphysics of Doubt’, in J.Cottingham (ed.) Readings in Philosophy: Descartes, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Williams, Michael 2001: ‘Experience & Reality’, in his The Problems of Knowledge: A Critical Introduction to Epistemology, Oxford: Oxford University Press.