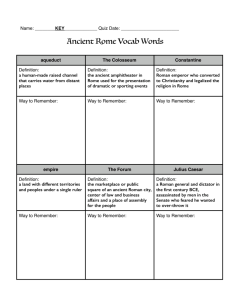

Review for the Final Examination

advertisement

Review for the Final Examination History 319: the Ancient World Tuesday, December 07, 2004 In its earliest form Christianity had the potential to alter familial relations profoundly. It challenged the old concepts of patriarchal dominance by suggesting that all members of the Christian community were equal and that the family of Christians had replaced the family of the secular world. Roman citizens were potentially capable of a full political life at Rome. In addition, they had certain rights in criminal law not possessed by anyone else. In A.D. 212, the emperor Caracalla extended Roman citizenship to almost everyone in the Empire. Honestiores and Humiliores: •Honestiores could claim special treatment under the law and were subject to much less stringent criminal punishments. •Those who belonged to the honestiores included first of all senators and equestrians, then decurions (local senators), soldiers, veterans, and some professionals. The scramble for citizenship became a scramble for inclusion in one of the higher classifications. (p. 383.) The Senate remained at the apex of the Roman social pyramid: •Even though the Senate lost its political power as a corporate, governing body, it never lost is social position. •In a status-conscious society, membership in the senatorial order represented the ultimate achievement of a man’s life. The Equestrian Civil Service The Decurion Class Collegia: burial societies. The purpose of collegia was to bury the dad and honor their memory with inscriptions and with celebrations at banquets at which all the members gathered. The Roman cult of the dead was deeply ingrained, and its perpetuation was of the utmost importance. If a family should die out, the burial society would indefinitely continue to honor the memory of its deceased, especially if they were benefactors. (pp. 392-393.) The collegia were open to all members of society, servile or fee, male or female, all classes could indulge in their desire to have a title, achieve some distinction, and be above someone else. Cinerary Urn This biconical cinerary urn dates to the Villanovan period (9th century BCE). Cremation was a common practice at this time, with the ashes of the deceased wrapped in linen or crimson colored fabric, placed in large vases of clay or bronze and buried with a few grave objects in an underground pit. The culture that immediately preceded that of the Etruscans is known as Villanovan, and Italian version of the great Urnfield culture found urm about the twelfth to the seventh century B.C. Urnfield culture, so called from its practice of burying the cremated remains of the dead in urns placed side by side by the hundreds, consisted of settled agricultural communities of some size that produced cereals and used the traction plough in place of the hoe or digging stick. Every known Etruscan city is preceded by a Villanovan settlement, a fact that has led to the debate about whether the Etruscans were transformed Villanovans or whether the new culture should be explained by the arrival of immigrants from somewhere else. (Nagle, p. 261.) ETRUSCAN TOMBS ETRUSCAN TOMBS Tomb of the Reliefs, Tarquinia (4th century B.C.) Tomb of Hunting and Fishing, Tarquinia (6th century B.C.) Tomb of the Leopards: Banqueting scene (6th century B.C.) Sarcophagus of the Married Couple, from Cerveteri, dating from 550 B.C. This sculpture depicts a wealthy Etruscan married couple reclining on a couch. Haruspices (singular, haruspex) were priests who practiced divination by the inspection of the entrails of animals. Piacenza Liver (4th century B.C.) The examination of the entrails of sacrificed animals, particularly the liver, was one of the principal branches of the disciplina Etrusca, the Etruscan art of divination. It was thought that the liver reflected the state of the world at the moment the sacrifice was made and thus could reveal the will of the gods as well as the future to those who could read the signs. In the ancient Near East the art of examining livers had been reduced to a standardized technique, and model terra-cotta livers were created to assist in the process of interpretation. In northern Italy, near Piacenza, a similar model liver in bronze was found in 1877. It is divided into 16 compartments with 24 inner division to which the names of various gods have been assigned. According to Cicero, the divisions on the left side of the sacrificial liver were unfavorable and those on the right favorable. Markings and unusual shapes and colorations could then be given a positive or negative interpretation by the priest and the results were passed on to the inquirer. (Nagle, pp. 258-259.) Pomerium: circle inscribed around the city by means of a plough. This circle designated the enclosed area as holy and protected against evil influences by its resident deities. Contact with this space ensured the inhabitants a continuous source of power deriving from its sacred character. p. 259. Ius, the term used for the secular concept of law, came to be applied to one body of law. Fas, which was reserved for sacred law, was applied to another. p. 270. Aeneas escaping the sack of Troy with his father and his son. The Twelve Tables Ancient Carthage Publius Cornelius Scipio Scipio’s first successes came in Spain, where he drove out the Carhaginians (210-205 B.C.) and established his reputation as a charismatic leader and a general of the caliber of Hannibal. Given the opportunity to invade Africa, he forced Hannibal’s withdrawal from Italy and then defeated him in a pitch battle at Zuma in 202 B.C., when for the first time Romans achieved cavalry superiority in the field. (Nagle, pp. 289-290.) iura: reciprocal rights of marriage, commerce, and probably also migration. Civitas optimo iure: full citizenship Civitas sine suffragio: citizenship without the vote Sui iuris: legally independent Potestas: under the control of someone else. Manus form of marriage Paterfamilias Consilium Materna auctoritas: The real influence of wives and mothers that may have been much greater than the strict letter of the law recognized. (pp. 297-298.) Clients, Patrons, and Fides Fides: A complicated network of mutual duties and obligations that bound clients and patrons together and, though not expressed in the terms of formal law, possessed great moral weight. pp. 299-300. Dignity, Honor and Order Distinctions in Roman society were based not on an individual’s professional skills or even wealth but rather on the capacity for public service in a broad sense. Romans looked for individuals who in war would be able to lead their armies and in peace would be looked up to as sources of wise legislation, jurisdiction, and religious guidance. With such an emphasis it is easy to see why honor (honor) and dignity (dignitas) were the two most important, interrelated values in Roman life and why community esteem rather than popularity was so important. p. 301. Cato the Elder (234 BC - 149 BC) With Cato the Elder, in the first half of the second century B.C., Latin history writing first came into existence, representing a new level of selfconfidence on the part of the Romans, who now rose to the challenge of Greek letters by composing their own literature in their own language. This was an achievement matched by no other people with whom the Greeks came into contact. For Cato, in fact, the Greeks no longer counted; the Romans and the Italians had nothing of which to be ashamed. On the contrary, he believed they had incorporated the best of the Greek world with the best of their own rich heritage—a pardonable exaggeration with which many Greeks in the second century B.C. must have agreed. From this time on, numerous accounts in Latin by members of the senatorial class provided the growing reading public of Rome and Italy with suitably patriotic, moralizing histories, often laced with polemic tracts from the internal political battles of the century. There were few qualms about adapting history to the political needs of the Roman upper classes, and history was seen as a means of glorifying one’s achievements and the achievements of one’s family as well as propagandizing for further advancement. Nagle, pp. 319-320. The Stoic Diogenes The Transformation of Rome When three famous Greek philosophers—Carneades, the head of the Academy; the Stoci Diogenes; and Critolaus the Peripatetic— came to Rome to plead a case on behalf of Athens, they electrified the youth of the city with their lectures. Carneades, the head of the Academy Nothing like Carneades’ lecture on justice and its application to the problem of empire, delivered on two successive days—on the second day of which the speaker refuted all the theories he had put up on the previous day—had been heard before. Cato urged that he philosophers be given a quick answer to their plea so that they could return to their schools in Athens as soon as possible, while the “youth of Rome could listen, as in the past, to their laws and magistrates.” Nagle, p. 320. Dionysus As Rome grew and the bonds of clientship (clientela) dissolved, the confinement of religion to the higher officials of state and to state functions created a vacuum. Eastern religions moved in to fill the void. The worship of the Great Mother (Magna Mater, Mater Deorum, or Cybele) was introduced officially in 205 B.C., and unofficially the worship of Dionysus crept into Italy and was savagely repressed as being dangerous to Rome both politically and morally. However, the two religions remained as the forerunners of many others, including the one that was ultimately to triumph: Christianity. Nagle, p. 321. Magna Mater, Mater Deorum, or Cybele Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus (The Gracchi Family) Gaius Marius (157-86 B.C.) and the Jugurthan War. Mithridates VI Lucius Cornelius Sulla 138-78 B.C. In 83 B.C., Sulla routed his opponents and initiated a reign of terror, showing himself once again an apt pupil of the violent politicians who had preceded him. To raise money and eliminate his political opponents, he hit upon a novel method of murder, the proscription list, which gave the names of his enemies together with the prices he was willing to pay for their deaths. Pompey Pompey defeats a pirate menace, and then between 66 and 62 B.C. he defeated Mithridates and expands Rome’s eastern territories. Crassus Caesar The Roman Empire under Augustus. The Roman Peace •Cultural pluralism and cultural unity •The purpose of the educational system was not merely to teach how to read and write but how to read and write well. •Like wealth and titles, culture was regarded as a mark of distinction and almost as eagerly sought. •Greek and Latin. •Focus on the classical texts •The ultimate goal of the educational system was the mastery of the spoken word. •There was no philosophy of education as a tool for socialization in the modern sense. Education was narrowly conceived as the prerogative of a small elite that had the time and the money to spend on it. Extending this kind of education broadly would have seemed absurd and probably impossible. The middle class strove for culture and advanced as far as their resources would permit them. City life •Greater degree of proximity between the classes •Trials, elections, public announcements, games, theater, religious celebrations, baths, gymnasia, markets. •Life was carried on in a very personal, intimate manner The rich were expected to make tangible contributions to the public life of the city by serving, unremunerated, as magistrates, giving festivals, maintaining the food and water supply, erecting public buildings, and generally contributing to the essentials of civilized life. (p. 372) The ranking of cities •Title of Roman colony •The Italian Right •Cities of Roman and Latin citizenship •Native cities •Villages •Districts Ludi: state festivals honoring gods. At the time of Augustus, the Roman calendar had 77 days of public games honoring the gods; within two centuries the number had risen to 176. •Circus races •Theaters •Raunch vaudeville Gladiatorial shows were originally staged as funeral games honoring the dead, and as a way of drawing attention to the virtue of the deceased. They were not financed by the state buy by the individual who felt he had an obligation (a munus; munera, pl.) to a dead person. (p. 375) •The munera became politicized. •The slaughter of animals had symbolic value •Perditi homines (prisoners of war, criminals, slaves) The great cultural diversity of the Empire was reflected in the chaotic variety of religions, cults, philosophies, and theosophies that offered themselves to the inhabitants of the Roman world. The emperor was the high priest and head of the Roman state religion, and as such responsible for maintaining right relations between the gods and humankind. While alive he was a semi divine intermediary between human beings and the gods, and when dead he was a god himself. (p. 377) Mithraism: An Iranian religion, Mithraism, was popular in the army and offered an attractive combination of doctrine, ritual, and ethical practice. Its adherents believed that the cosmos was in constant tension between the forces of good and evil, light and darkness, life and death. (p. 378.) Excluded women Health of Paganism? pp. 378-379. Judaism and Christianity: Judaism and Christianity were both exclusive in the membership and both placed emphasis on the close adhesion to strict ethical practices and dogmatic beliefs. The liturgy of Judaism and Christianity had the advantages of both the philosophers’ lecture hall and the sense of community and brotherhood of the mystery cults. To the Jewish belief that God was the Lord of History, Christians added the assertion that history had found its culmination in the lowly person of Jesus of Nazareth, who was executed by the imperial prefect Pontus Pilate during the reign of the emperor Tiberius. (p. 379.) Among the major issues settled in the early years of the Christian community was the question of whether Jesus’ message was to be limited to Jews or could be extended to gentiles as well. One of the principal figures in this momentous debate was a Hellenized Jew, Paul of Tarsus. Rabbinic Judaism (The destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem by the Romans in A.D. 70.