winter count

advertisement

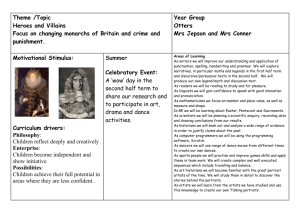

Pictographs Communities are defined by their languages, cultures, and histories. The languages of Native Americans were not traditionally written. They were only spoken, which meant that tribal histories and other important information had to be remembered by people and passed down verbally from generation to generation. This is what is known as an oral tradition. Sometimes, Native communities used creative tools to help them remember their complex histories. A winter count was one such tool that certain Native American communities of the Northern Great Plains region used to help record their histories and to keep track of the passage of years. Here is how it worked: in these communities, the annual cycle was measured not from January through December; but rather from the first snowfall to the next year’s first snowfall. This entire year was sometimes referred to as a winter. Near the end of each year, elders in each community met for an important discussion. They talked about the things that had happened since the first snowfall and they chose one particular event to serve as a historical reminder for the whole year. The year was then forever named after the chosen event. It then became the responsibility of one person in the community to design and paint onto a buffalo hide a pictograph, a picture that symbolized the event. The keeper, as this person was known, painted a new pictograph on the hide each year to commemorate that year’s event. The hide, with all of its symbols representing the community’s history, was known as the winter count. The important job of keeping the winter count was often passed down from father to son in the same family. If the images on a winter count faded or if the hide became worn, the keeper would make a new copy to preserve the information. Some winter counts were also drawn on paper or cloth. The winter count keeper was also a storyteller. These storytellers were very important to the oral tradition because it was their job to preserve and pass along the community information. By using the winter count, the storyteller was able to teach community members about their history and to answer questions about events that had occurred in the past. The winter count served as a mnemonic device. This means that the pictographs drawn on it helped the people remember lots of things that happened each year. For example, when we look at a family photograph today, it can remind us of many things about the people in the picture. By looking at a pictograph on a winter count, community members could recall not only the event that the year was named for, but other things too, such as when babies were born, when marriages took place, or when new leaders were chosen. As a record of history, the winter count reminded the people of who they were and where they had come from, in the same way that our written histories serve today. This helped keep the community strong and united because it was the connection to their past. In an oral tradition such as that of the Nakota, remembering history was a very important job that was done with seriousness, respect, and utmost care. This is why winter counts were so important to the American Indian communities that used them. Special Clothing All cultures celebrate special occasions and events in people’s lives. In honor of celebrations, people often dress up and wear certain clothes or items to fi t the occasion. Can you think of some special occasions for which you dress up? What do you wear? Among the Assiniboine and Sioux, two Northern Plains tribes from Montana, cultural events and celebrations require special attire. For girls, special attire can be a beaded dress made of elkhide or deerhide—or a cloth dress covered with shells, elk teeth, or cone-shaped tin “jingles.” For men and boys, it might be a beaded outfi t consisting of a belt, moccasins, vest, headband, and other items. Some special occasions for which Plains people wear traditional clothing today are weddings, naming ceremonies (where a person gets a name in their Native language), community celebrations, honoring “giveaways” (celebrations in which things of value are given away to honor someone), and powwows (Native dance festivals and competitions). Whatever the occasion, the people of the Plains have always taken great pride in wearing their traditional clothes, sometimes referred to as regalia. A tremendous amount of time and effort goes into making regalia. For the girls and women of Plains tribes, the dress that one wears for special occasions is more than just a pretty dress. A dress connects a girl to her tribe, her community, her family, and her ancestors. The dresses that girls and women wear are full of meaning, sometimes decorated with beads in designs and symbols that tell stories in honor of family members. Long ago, the decorations on a woman’s dress signaled her family’s ability to trade for materials, or that her husband or father was a good provider. Many elk teeth on a dress meant great wealth. In the Crow tribe, dresses covered in elk teeth were sometimes given to a new daughter-in-law by her husband’s family. The only elk teeth used on dresses are the two ivory eyeteeth. In the past, a boy would collect elk teeth over many years of hunting and would save them to be sewn by his mother or sisters on a dress for the woman he would marry. Storytelling All cultures seek to answer the basic questions of where we humans came from and why we’re here on earth. Their answers take the form of philosophies, religions, legends, mythology, and in Native American Indian cultures, storytelling is a dominant means for understanding. Humans are storytelling animals. Through story we explain and come to understand ourselves. Story—in creative combination with encounter, experience, image making, ritual, play, imagination, dream, and modeling, forms the basic foundation of all human learning and teaching. One of the primary learning techniques of Native American Indian Tradition is the Story Circle. There are actually many hundreds of ways to use the circle, from everyone telling a long traditional story, to passing a story stick in silence from one person to the next. The circle is a metaphor for the larger circle of the world and the process of using the circle signifies our role in the cycle of life. Native American storytelling was and still is a communal experience. It brings people together to share a past that is still alive. The events in the stories, though they may seem fantastic and unlikely, can also be experienced as a type of reality. Stories may show us important things about the world we live in and teach us ways to behave in that everyday world. In traditional settings, a storyteller is not speaking to an audience, but instead engages people in the tale. If a storyteller asks a question, he or she expects an answer. If there is a song within a story, that song will be known by or taught to the people. To Native American Indian people, stories are among the greatest gifts which human beings have been given. The way the storytellers were regarded by their people shows this. Because Native American Indian cultures had an understanding of this powerful role of story and its cross-generational value, people of all ages gathered around when a story was told. From our knowledge of different Native American Indian cultures, we know that storytelling was not “just for children.” In fact, stories were so powerful that they were treated with a special respect. Many stories, in fact, could be told only by certain people at specific times. Because certain men and women showed more ability than others, there were sometimes specific individuals who acted as “professional” storytellers. Among the Iroquois, these people had the title of Hage’ota, “a story person or storyteller.” These people traveled from lodge to lodge during the storytelling seasons. Basic Native American environmental themes like sustainability and biodiversity, as well as a process with which watersheds and salmon can be understood, are at the heart of the stories you will be reading. When people recognize their relationship with the rest of the natural world, they feel empowered to learn. “The care of the rivers,” an elder said, “begins in the human heart.” Dance Dances have always been significant in the lives of Native Americans as both a common amusement and a solemn duty. Many dances played a vital role in religious rituals and otherceremonies; while others were held to guarantee the success of hunts, harvests, giving thanks, and other celebrations. Commonly, dances were held in a large structure or in an open field around a fire. Movements of the participants illustrated the purpose of the dance -- expressing prayer, victory, thanks, mythology and more. Sometimes a leader was chosen, on others, a specific individual, such as a war leader or medicine man would lead the dance. Many tribes danced only to the sound of a drum and their own voices; while others incorporated bells and rattles. Some dances included solos, while others included songs with a leader and chorus. Participants might include the entire tribe, or would specific to men, women, or families. In addition to public dances, there were also private and semi-public dances for healing, prayer, initiation, storytelling, and courting. Dance continues to be an important part of Native American culture. The dances are regionally or tribally specific and the singers usually perform in their native languages. Depending upon the dance, sometimes visitors are welcomed; while, at other times, the ceremonies are private. There were a number of semi-religious festivals or ceremonies in which a large number of individuals participated which were handed from one tribe to another. One of the best known examples of the Plains Indians was the Omaha or Grass Dance which was also practiced by the Arapaho, Pawnee, Omaha, Dakota, Crow, Gros Ventre, Assiniboin, and Blackfoot. Its regalia is thought to have originated with the Pawnee, who taught the dance to the DakotaSioux in about 1870. The Sioux, in turn, shared it with the Arapaho and Gros Ventre, who taught it to the Blackfoot. Later, the Blackfoot carried the dance to the Flathead and Kootenaitribes to the west. Meetings of these associations were held at night in large circular wooden buildings erected for that purpose. Some of the dancers wore large feather bustles, called crow belts, and a peculiar roached headdress made of hair. A feast of dog's flesh was often served. Members of some of these associations were often known to have helped the poor and practice acts of self-denial. Other dances, such as the Cree Dance, Gourd Dance, and horseback dances also had associations. However, from tribe to tribe, each had its own distinct ceremonies and songs, to which additions were made from time to time.