Jainism: To Do No Harm - White Plains Public Schools

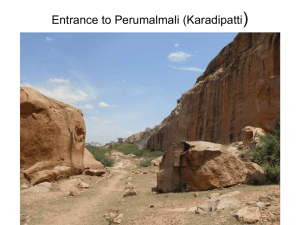

advertisement

Although the majority of Indians follow the Hindu path, India has given birth to several other religions which are not based on the Vedas One of them is Jainism Jainism has never condoned war or the killing of animals for any reason Its major teacher is Mahavira (“The Great Hero”) Mahavira was a contemporary of the Buddha who died approximately 526 B.C.E. Like the Buddha, he was the prince of a kshatriya clan and renounced his position and his wealth at the age of thirty to wander as a spiritual seeker Finally after twelve years of meditation, silence, and fasting, Mahavira achieved liberation and perfection For thirty years until his death at Pava, he spread his teachings His followers came from all castes, as Jainism does not officially acknowledge the caste system The Jain teachings are not thought to have originated with Mahavira, however He is considered the last of the twenty-four Tirthankaras (“Fordmakers”) of the current cosmic cycle In Jain cosmology, the universe is without beginning or end Eternally it passes through long cycles of progress and decline At the beginning of each downward cycle, humans are happy and virtuous and have no need for religion As these qualities decline, humans look first to elders for guidance, but as things get worse Tirthankaras must create religion in order to steer people away from the growing evilness of the world The twenty-second Tirthankara is generally acknowledged by scholars as an historic figure, Lord Krishna’s cousin, renowned for his compassion toward animals During his wedding procession, it is said that he heard the groans of animals who were to be slaughtered and immediately decided not to marry since so many innocent animals would be killed to feed the wedding guests He became an ascetic who preached religion for many years and his betrothed princess became an ascetic nun The extreme antiquity of Jainism as a non-Vedic, indigenous Indian religion is well documented Ancient Hindu and Buddhist scriptures refer to Jainism as an existing tradition which began long before Mahavira After Mahavira’s death, his teachings were not written down at first because the monks lived as ascetics without possessions; they were initially carried orally by memory In the third century B.C.E., the great Jain saint Bhadrabahu predicted that there would be a prolonged famine where Mahavira had lived, in what is now Bihar in northeast India He led some twelve thousand monks to South India to avoid the famine, which lasted for twelve years When they returned to their original home, they discovered that two major changes had been introduced by the monks who had remained in the area One was relaxation of the requirement of nudity for monks,; the other was the convening of a council to edit the existing Jain texts into an established canon of fortyfive books Eventually the two groups split over their differences into the Digambaras who had left and did not accept the changes as authentic to Mahavira, and the Svetambaras who had stayed near his original location Two major differences remain between the ascetic orders today Digambara (“sky clad”) monks wear nothing at all, symbolizing their innocence of shame and their non-attachment to material goods They do not consider themselves “nude”; rather, they have taken the environment as their clothing, thus damaging it as little as possible by stoically enduring all kinds of weather Digambara monks have only two possessions: a broom of feathers dropped by peacocks and a gourd for drinking water The Svetambaras (“white-clad”) feel that wearing a piece of white cloth does not prevent them from attaining liberation The two orders also differ over the subject of women’s abilities Digambaras believe that women do not have the strong body and willpower needed to attain liberation; they can only be liberated if they are reborn in a man’s body Svetambaras feel that women are capable of the same spiritual achievement as men, and that the nineteenth Tirthankara was a woman The influence of Jainism was overshadowed by the growing popularity of devotional bhakti ways of India, but the tradition has never died out Jain merchants, monks, and nuns still practice teachings which have not changed much in two thousand years Jains are given to great hope The jiva – the individual’s higher consciousness, or soul – can save itself by discovering its own perfect, unchanging nature and thus transcend the miseries of earthly life This process may require many incarnations Jains, like Hindus and Buddhists, believe that individuals are reborn again and again until they finally free themselves from samsara, the wheel of birth and death The gradual process by which the soul learns to extricate itself from the lower self and its attachments to the material world involves purifying one’s ethical life until nothing remains but the purity of the jiva In its true state, the jiva is omniscient, shining, self-contained, and blissful One who has thus brought forth the highest in his or her being is called a Jinni (a “winner” over the passions), from which the term Jain is derived The Tirthankaras were Jinas who helped others find their way, regenerating the community by teaching inspiring spiritual principles Like Hindus and Buddhists, Jain believe that our actions influence the future course of our current life, and of our lives to come But in Jain belief, karma is actually subtle matter – minute particles that individuals accumulate as they act and think Mahavira likened karma to coats of clay that weigh down the soul Jains are very careful to avoid accumulating karma Three of the chief principles to which they adapt their lives are ahimsa (non-violence), aparigraha (non-attachment), and anekantwad (nonabsolutism) Ahimsa is the principle of nonviolence and is very strong in Jain teachings, and through Jainism it also influenced Mahatma Gandhi Jains believe that every centimeter of the universe is filled with living beings, some of them minute A single drop of water contains three thousand living beings All of them want to live Humans have no special right to supremacy; all things deserve to live and evolve as they can To kill any living being has negative karmic effects It is difficult not to do violence to other creatures As individuals walk, they can unknowingly squash insects Even in breathing, Jains feel that individuals inhale tiny organisms and kill them Jains avoid eating after sunset, so as not to inadvertently eat unseen insects who might have landed on the food, and some Jain ascetics wear a cloth over their mouth to avoid inhaling any living organisms The higher the life-form, the heavier the karmic burden of its destruction Levels of life are determined by their degree of sensitivity The highest group of beings are those with many senses, such as humans, gods, and higher animals Lower forms have fewer senses The Jain sutras describe the suffering of even these one-sensed beings; their agony at being wounded is like that of a blind and mute person who cannot see who is hurting him or express the pain Jains are therefore strict vegetarians, and they treat everything with great care In Delhi, Jain benefactors have established a unique hospital for sick and wounded birds Great attention is paid to their every need, and their living quarters are air-conditioned in the summer Jains also go to market where live animals are usually bound with wire, packed into hot trucks, and driven long distances without water, to be killed as meat Jains buy the animals at any price and raise them in comfort Even to kick a stone while walking is to injure a living being Ahimsa also extends to care in speaking and thinking, for abusive words and negative thoughts can injure another One’s profession must also not injure beings, so most Jains work at jobs considered harmless, such as banking, clerical occupations, education, law, and publishing Agriculture is considered harmful, for in digging into the soil one harms minute organisms in the earth; in harnessing bullocks to plows or water buffalos to carts, one would harm not only the bullock or buffalo but also the tiny life forms on its body Another central Jain ideal is non-attachment to things and people An individual should cut his living requirements to a bare minimum Possessions possess individuals; their acquisition and loss drive emotions The story is told of a muni (monk) who saw twelve stray dogs chasing another dog who was racing away with a bone he had found When they caught the dog, they attacked him to wrest it from his jaws Wounded and bleeding, he let go of it The others immediately abandoned him to chase the one who picked it up The monk saw the scene as a moral lesson: So long as individuals cling to things, individuals have to bleed for them When individuals let them go, individuals will be left in peace The third central principle is anekantwad, roughly translated as “relativity” Jains try to avoid anger and judgementalism, remaining open-minded by remembering that any issue can be seen from many angles, all partially true Jains tell the story of the blind men who are asked to describe an elephant The one who feels the trunk says an elephant is like a tree branch The one grasping a leg argues that an elephant is like a pillar The one feeling the ear asserts that an elephant is like a fan The one grasping the tail insists that an elephant is like a rope And the one who encounters the side of the elephant argues that the others are wrong; an elephant is like a wall Each has a partial grasp of the truth In the Jain way of thinking, the fullness of truth has many facets There is no point in finding fault with others; our attention must be directed to cleansing and opening our own vision As the Jain Shree Chitrabhanu states, “See how easily you meet people when there is no feeling of greater or lesser, no scar or bitterness, no faultfinding or criticism.” Jainism is an ascetic path and thus is practiced in its fullest by monks and nuns Monks practice meditation and adopt a life of celibacy, physical penance and fasting, and material simplicity At initiation, they may pull their hair out by the roots rather than be shaved However, lay people exist In New Delhi, a wealthy sixty-year-old Jain businessman, head of a large construction company, astounded people in 1992 by moving from lay austerities such as eating and drinking only once in twenty-four hours to the utterly renunciate life of a naked Digambara monk “Difficult to conquer is oneself; but when that is conquered, everything is conquered.” ~Uttaradyayana Sutra 9.34-36 Of course, most householders cannot carry renunciation as far as monks and nuns, but they can nonetheless purify and perfect themselves Jain homes and temples are scrupulously clean, their diets carefully vegetarian, and the medicines they use are prepared without cruel testing on animals The mind and passions are also to be held under strict control Jains believe that the universe is without beginning and that it has no creator or destroyer Lives are therefore the results of individual deeds; only by individual efforts can selves be saved Padma Agrawal explains, “In Jainism, unlike Christianity and many Hindu cults, there is no such thing as a heavenly father watching over us. To the contrary, love for a personal God would be an attachment that could only bind Jains more securely to the cycle of rebirth. It is a thing that must be rooted out.” According to Jains, the world operates by the power of nature, according to natural principles Jains do believe in gods and demons, but the former are subject to the same ignoble passions as humans In fact, one can only achieve liberation if one is in the human state, because only humans can clear away karmic accumulations on the soul Until it frees itself from karmas, the mundane soul wanders about through the universe in an endless cycle of deaths and rebirths, instantly transmigrating into another kind of being upon death of its previous body Birth as a human is prized by Jains as the highest stage of life short of liberation One should therefore lose no time in this precious, brief period in human incarnation, for within it lies the potential for perfection Householders can journey toward the final state by passing through fourteen stages of ascent of the soul, or gunasthana Throughout the process, the veils of karma are lifting and the soul experiences more and more of its natural luminosity In the highest state of perfection, known as kevala, all gross activities have come to an end, and the being is liberated Although severe vows of renunciation can be taken by householders, lay spiritual life is more likely to consist of six duties: 1. The practice of equanimity through meditation 2. Praise of the Tirthankaras 3. Veneration of teachers (who live as mendicants) 4. Making amends for moral transgressions 5. Indifference to the body (often by holding a particular position for a length of time) 6. Renunciation of foods or activities for specific periods Practicing strict ethics and self-control Jains are often quite successful and trusted in their professions…Many Jains thus become wealthy And while people pay respects before images of Tirthankaras with offerings and waved lamps, they do not expect any reciprocation from them Liberation from samsara is a result of personal effort Acharya Tulsi expressed the Jain point of view: “The primary aim of Dharma is to purify character. Its ritualistic practices are secondary.”