Chapter 20 Summary Mainstream politicians, both northerners and

advertisement

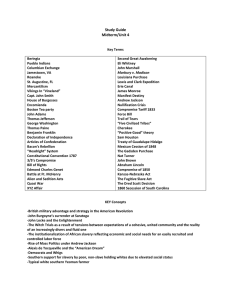

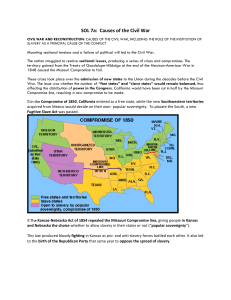

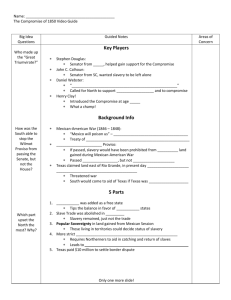

Chapter 20 Summary Mainstream politicians, both northerners and southerners, tried to stay out of the slavery debate; they were appalled that fanatics should be playing an ever-increasing role in political discourse. Slavery had come to be defined as a “domestic institution” within each state. Congress had the authority to legislate concerning slaves who fled across a state line. Southerners demanded a new fugitive slave law that northerners could not easily evade. Until the acquisition of Mexico’s land, the expansion of slavery beyond the slave states was a dead letter. The Mexican War changed all that. The Wilmot Proviso stated that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist” in lands taken from Mexico after the war. The proviso was killed in the Senate. In 1848, Zachary Taylor narrowly won the presidency. With the discovery of gold, the population of California increased to about 100,000 by the end of 1849. A large majority of southern senators and congressmen declared they would vote against California statehood. When Congress convened, sectional animosities were boiling. Henry Clay saw in the mess of bills the possibility of a great compromise that might put an end to sectional bitterness. Two decades earlier, Clay’s Omnibus Bill would likely have sailed through Congress. Extremists from both sections refused to support Clay’s compromise because they found one or another of its provisions unacceptable. After his sudden death, Taylor was succeeded by Millard Fillmore, who was willing to support compromise. Senator Stephen Douglas revived Clay’s design for compromise, but not in the form of one comprehensive bill. The Congress of 1849-1851 saw the nation’s second generation of political leaders-the men of the age of Andrew Jackson--pass the torch to a third. The Whig party dwindled after 1850. Most northern Democrats were friendly to the South and slavery, but to different degrees. In 1852, Americans elected for president Franklin Pierce, a man not well-suited to the issues of the time. As thoughts turned to connecting California to the rest of the nation, Douglas wanted the transcontinental railroad’s eastern terminus in Chicago. He hatched a scheme to seduce southern senators by playing on their obsession: slavery. In May 1854, he introduced a bill to establish the Kansas and Nebraska territories, with each becoming states on the basis of popular sovereignty. Douglas’s popularity soared in the South. After 1830, the Catholic population steadily increased due to massive immigration from Ireland and the Catholic states of Germany. The Know-Nothings were able to appeal to voters in both North and South by claiming that the furor over slavery was a distraction from the important issues: jobs for native Americans, political corruption, and the flood of immigrants. Unlike the Democrats, Whigs, and Know-Nothings, the Republicans were a purely sectional party. They demanded the repeal of the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the exclusion of slavery from all the western territories.