L11 Tensor properties, elastic anisotropy, part 4

advertisement

1

27-301

Microstructure-Properties

L11: Tensors and Anisotropy, Part 4

Profs. A. D. Rollett, M. De Graef

Processing

Performance

Microstructure Properties

Last modified: 25th Oct. ‘15

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

2

Objective

• The objective of this lecture is to provide a

mathematical framework for the description of

properties, especially when they vary with

direction.

• A basic property that occurs in almost

applications is elasticity. Although elastic

response is linear for all practical purposes, it is

often anisotropic (composites, textured

polycrystals etc.).

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

3

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Questions & Answers

Why is it useful to rotate/transform the compliance tensor or matrix? Often we

need to compute the elastic modulus in some particular direction that is not

[100] or [111]. Why do we compute the compliance rather than the stiffness in

the 1-direction? This is subtle: we use compliance because one can impose a

stress state that has only one non-zero component, from which we only need

the strain component parallel to it. Poisson’s ratio tells us that imposing a strain

in one direction automatically results in lateral strains (unless n=0), which means

that it is not possible to have one and only one strain component contributing to

a particular stress component.

How are the quantities in the equation for the rotated/transformed s11 related

to the same equation with the Young’s moduli in the <100> and <111>

directions? Comparison of the two formulae shows how to relate the three S

values to the Youngs’ moduli in the two directions.

What is Zener’s anisotropy ratio? C' = (C11 - C12)/2; Zener’s ratio = C44/C’.

Which materials are most nearly isotropic? W at room temperature is almost

isotropic and Al is not quite so close to being isotropic.

How do we apply the equations to calculate the variation in Young’s modulus

between [100] and [110] in a cubic metals such as Cu? Direction cosines are the

quantities that are needed to define the direction in relation to the crystal axes.

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

4

Q&A - 2

6.

7.

8.

9.

What are the Lamé constants? These are the two constants l and G that are

needed for isotropic elasticity. What do they have to do with isotropic elasticity?

G has its usual meaning of shear modulus, or C44: see the notes for how they

relate to C11 and C12. How do they relate to Young’s modulus, bulk modulus and

Poisson’s ratio? See the notes for the formulae.

How do we write the piezoelectric matrix for quartz? 6x3 matrix. What stimuli and

responses do each coefficient in the “d” matrix relate? Stimulus is the electric field

and the response is the strain. What are the “BT” and “AT” cuts of a quartz

crystal? These are cuts that maximize the usefulness of the thickness shear mode

of oscillation.

What equation describes the resonant frequency? See the notes. Why does

temperature matter here? Temperature matters because one prefers to have a

crystal that does not change its resonant frequency with temperature. Why does

the density vary as the sum of 2a11+a33? This sum is the trace of the matrix for the

coefficient of thermal expansion, i..e the variation in volume with change in T.

How does the angle q relate to the AT and BT cuts already described? This angle is

a rotation of the normal to the surface of the crystal in the y-z plane (i.e. rotation

about x). How do we set up the equation that tells us the variation in d66 with

angle of cut? The Eq we need is that which describes the rate of change of

resonant frequency with temperature.

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

5

Rotated compliance (matrix)

Given an orientation aij, we transform the compliance tensor,

using cubic point group symmetry:

Writing this out in full for the 1111 component:

Re-writing this with vector-matrix notation gives:

(

S1¢ 1 = S1 1 a141 + a142 + a143

(

)

)

+ 2S1 2 a1 2a1 3 + a1 1a1 2 + a1 1a1 3

(

2

2

2

2

2

2

+ S4 4 a1 2a1 3 + a1 1a1 2 + a1 1a1 3

2

2

2

2

2

2

)

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

6

Rotated compliance (matrix)

• This can be further simplified with the aid of the standard

relations between the direction cosines,

aikajk = 1 for i=j; aikajk = 0 for ij, (aikajk = ij)

to read as follows:

s1¢ 1 = s1 1 -

(

){

2 s1 1 - s1 2 - 1 s4 4 a12 a 22 + a 22 a 23 + a 32a 12

2

}

• By definition, the Young’s modulus in any direction is given by

the reciprocal of the compliance, E = 1/S’11.

• Thus the second term on the RHS is zero for <100> directions

and, for C44/C'>1, a maximum in <111> directions (conversely

a minimum for C44/C'<1).

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

7

Anisotropy in terms of moduli

• Another way to write the above equation is to

insert the values for the Young's modulus in the

soft and hard directions, assuming that the <100>

are the most compliant direction(s). (Courtney

uses a, b, and g in place of my a1, a2, and a3.)

The advantage of this formula is that moduli in

specific directions can be used directly.

ì 1

1

1

1 ü 2 2

2 2

2 2

=

- 3í

ý(a1 a 2 + a2 a 3 + a3 a1 )

Euvw E100 î E100 E111þ

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

8

Cubic crystals: anisotropy factor

• If one applies the symmetry elements of the

cubic system, it turns out that only three

independent coefficients remain: C11, C12 and

C44, (similar set for compliance). From these

three, a useful combination of the first two is

C' = (C11 - C12)/2

• See Nye, Physical Properties of Crystals

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

9

Zener’s anisotropy factor

• C' = (C11 - C12)/2 turns out to be the stiffness

associated with a shear in a <110> direction on a

{110} plane. In certain martensitic

transformations, this modulus can approach zero

which corresponds to a structural instability.

Zener proposed a measure of elastic anisotropy

based on the ratio C44/C'. This turns out to be a

useful criterion for identifying materials that are

elastically anisotropic.

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

10

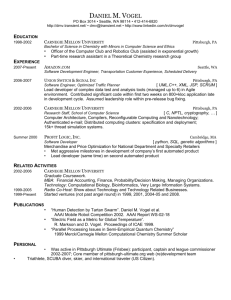

Anisotropy in cubic materials

• The following table shows

that most cubic metals have

positive values of Zener's

coefficient so that <100>

is most compliant and

<111> is most stiff,

with the exceptions of V, Nb

and NaCl.

Material

Cu

Ni

A1

Fe

Ta

W (2000K)

W (R.T.)

V

Nb

b-CuZn

spinel

MgO

NaC1

C44/C'

3.21

2.45

1.22

2.41

1.57

1.23

1.01

0.78

0.55

18.68

2.43

1.49

0.69

E111/E100

2.87

2.18

1.19

2.15

1.50

1.35

1.01

0.72

0.57

8.21

2.13

1.37

0.74

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

11

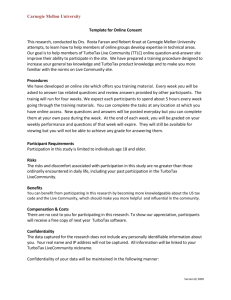

Stiffness coefficients, cubics

Units:

1010 Pa

or

10 GPa

Nb (niobium): beta1=17:60 (TPa)-1 , Bcub= 0.50. s11 = 6.56, s44 = 35.20, s12 = -2.29 (in (TPa)-1 ). Emin = 0.081,

Emax = 0.152 GPa.

12

Example Problem

[Courtney]

Should be E<111>= 18.89

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

13

Lamé constants

(isotropic elasticity)

For an elastically isotropic body, there are only 2

elastic moduli, known as the Lamé constants.

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

14

Young’s, Bulk moduli, Poisson’s ratio

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

15

Engineering with the

Piezoelectric Effect

•

•

•

[Newnham, sections 12.8 and 13.10] The use of quartz as a resonant crystal for

oscillator circuits with highly stable frequency depends strongly on the details of

its properties.

Although quartz is only weakly piezoelectric, other aspects of its properties

provide the key, namely thermal stability.

Most elastic stiffness coefficients have negative temperature coefficients,

meaning that materials become less stiff with rising temperature. The c66

coefficient of quartz, however, is positive; Table 13.7. This offsets the effect of

thermal expansion, which increases dimensions and decreases density. This is

what makes it possible to have an oscillator that is insensitive to temperature

changes.

d11 = 2.27; d14 =-0.67 pC/N

http://en.wikipedia.org/

wiki/Electromagnetic_aco

ustic_transducer

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

16

Quartz Oscillator Crystals, contd.

• Resonant frequency, f, for thickness (t)

shear mode, as a function of the rotation

of axes to get c’66, where r is the density:

• AT and BT cut modes are thickness shear

modes driven by the piezoelectric

coefficient d’26:

e’6 = d’26 E’2

A particular angle must

be determined for the

ideal cut to minimize the

temperature

dependence of the

resonant frequency.

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

17

Quartz Oscillator Crystals, contd.

• Temperature dependence of the resonant frequency, f, for

thickness (t) shear mode, as a function of the rotation of axes

to get c’66, where r is the density:

• Temperature derivative of the density:

• Temperature derivative of the thickness in the Z’2 (Y’) direction:

• Transformed (rotated) stiffness coefficient:

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

18

Quartz Oscillator Crystals, contd.

• Quartz belongs to point group 23. Therefore c1313 = c55 = c44

and c1213 = c65 = c56 = c14.

• Taking the temperature derivative for c’66 and substituting all the

relevant values into the equation, one obtains the following. Here,

“T(c66)” denotes the temperature coefficient of the relevant stiffness

coefficient (Table 13.7). The derivative of the resonant frequency, f,

can be set equal to zero in the standard fashion in order to find the

minima.

• Applying the solution procedure yields two values with theta = 35° and +49°, corresponding to the two cuts illustrated.

• Further discussion is provided by Newnham on how to make AC

and BC cuts that are useful for transducers for transverselypolarized acoustic waves.

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

19

Summary

• We have covered the following topics:

– Examples of elastic property values

– Anisotropy coefficients (Zener)

– Dependence of Young’s modulus on direction (in a

crystal)

– Worked example

– Quartz oscillator crystals

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

20

Supplemental Slides

• The following slides contain some useful material

for those who are not familiar with all the

detailed mathematical methods of matrices,

transformation of axes etc.

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

21

Notation

F

R

P

j

E

D

e

r

d

Stimulus (field)

Response

Property

electric current

electric field

electric polarization

Strain

Stress (or conductivity)

Resistivity

piezoelectric tensor

C

S

a

W

I

O

Y

e

T

elastic stiffness

elastic compliance

rotation matrix

work done (energy)

identity matrix

symmetry operator (matrix)

Young’s modulus

Kronecker delta

axis (unit) vector

tensor, or temperature

a direction cosine

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

22

Bibliography

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

R.E. Newnham, Properties of Materials: Anisotropy, Symmetry, Structure, Oxford

University Press, 2004, 620.112 N55P.

De Graef, M., lecture notes for 27-201.

Nye, J. F. (1957). Physical Properties of Crystals. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

Kocks, U. F., C. Tomé & R. Wenk, Eds. (1998). Texture and Anisotropy, Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, UK.

T. Courtney, Mechanical Behavior of Materials, McGraw-Hill, 0-07-013265-8, 620.11292

C86M.

Landolt, H.H., Börnstein, R., 1992. Numerical Data and Functional Relationships in

Science and Technology, III/29/a. Second and Higher Order Elastic Constants. SpringerVerlag, Berlin.

Zener, C., 1960. Elasticity And Anelasticity Of Metals, The University of Chicago Press.

Gurtin, M.E., 1972. The linear theory of elasticity. Handbuch der Physik, Vol. VIa/2.

Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp. 1–295.

Huntington, H.B., 1958. The elastic constants of crystals. Solid State Physics 7, 213–351.

Love, A.E.H., 1944. A Treatise on the Mathematical Theory of Elasticity, 4th Ed., Dover,

New York.

Newey, C. and G. Weaver (1991). Materials Principles and Practice. Oxford, England,

Butterworth-Heinemann.

Reid, C. N. (1973). Deformation Geometry for Materials Scientists. Oxford, UK,

Pergamon.

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides

23

Transformations of Stress & Strain Vectors

• It is useful to be able to transform the axes of s ¢i = a ijs j

stress tensors when written in vector form

-1

s

=

a

i

ij s ¢j

(equation on the left). The table (right) is

taken from Newnham’s book. In vector-matrix e¢i = a -1T

ij e j

form, the transformations are:

ei = a Tij e¢j

æ s1¢ ö éa11

ç ÷ ê

çs ¢2 ÷ êa 21

çs ¢3 ÷ êa 31

ç ÷=ê

çs 4¢ ÷ êa 41

çs ¢5 ÷ êa 51

ç ÷ ê

ès ¢6 ø ëa 61

a12

a 22

a 32

a 42

a 52

a 62

a13

a 23

a 33

a 43

a 53

a 63

a14

a 24

a 34

a 44

a 54

a 64

a15

a 25

a 35

a 45

a 55

a 65

a16 ùæ s1 ö

úç ÷

a 26 úçs 2 ÷

a 36 úçs 3 ÷

úç ÷

a 46 úçs 4 ÷

a 56 úçs 5 ÷

ç ÷

a 66 úûès 6 ø

Please acknowledge Carnegie Mellon if you make public use of these slides