Outline of this course:

Business Cycle Models

Chapter objectives

difference between short run & long run

introduction to aggregate demand

aggregate supply in the short run & long run

see how model of aggregate supply and demand can be used to analyze short-run and long-run effects of “shocks”

Real GDP Growth in the U.S., 1960-2004

10

8

6

4

Average growth rate = 3.4%

2

0

-2

-4

1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005

Time horizons

Long run:

Prices are flexible, respond to changes in supply or demand

Short run: many prices are “sticky” at some predetermined level

The economy behaves much differently when prices are sticky.

In Classical Macroeconomic Theory

Output is determined by the supply side:

– supplies of capital, labor

– technology

Changes in demand for goods & services

( C , I , G ) only affect prices, not quantities.

Complete price flexibility is a crucial assumption, so classical theory applies in the long run.

When prices are sticky

…output and employment also depend on demand for goods & services, which is affected by

fiscal policy ( G and T )

monetary policy ( M )

other factors, like exogenous changes in C or I .

AD/AS Model

the paradigm that most mainstream economists & policymakers use to think about economic fluctuations and policies to stabilize the economy

shows how the price level and aggregate output are determined

shows how the economy’s behavior is different in the short run and long run

Aggregate demand

The aggregate demand curve shows the relationship between the price level and the quantity of output demanded.

For this chapter’s intro to the AD/AS model, we use a simple theory of aggregate demand based on the Quantity Theory of

Money.

Chapters 10-11 develop the theory of aggregate demand in more detail.

The Quantity Equation as AD

M V = P Y

For given values of M and V , these equations imply an inverse relationship between P and Y:

The downward-sloping AD curve

(

An increase in the price level causes a fall in real money balances

M/P ), causing a decrease in the demand for goods

& services.

P

AD

Y

Shifting the AD curve

P

An increase in the money supply shifts the AD curve to the right.

AD

1

AD

2

Y

Aggregate Supply in the Long Run

In the long run, output is determined by factor supplies and technology

Y F K L )

Y is the full-employment or natural level of output, the level of output at which the economy’s resources are fully employed.

“Full employment” means that unemployment equals its natural rate.

The long-run aggregate supply curve

P LRAS

The LRAS curve is vertical at the full-employment level of output.

Y

Y

Long-run effects of an increase in M

P LRAS

An increase in M the shifts

AD curve to the right.

In the long run, this increases the price level…

P

2

P

1

…but leaves output the same.

Y

AD

1

AD

2

Y

Aggregate Supply in the Short Run

In the real world, many prices are sticky in the short run.

For now (and throughout Chapters 9-11), we assume that all prices are stuck at a predetermined level in the short run…

…and that firms are willing to sell as much at that price level as their customers are willing to buy.

Therefore, the short-run aggregate supply

(SRAS) curve is horizontal:

The short run aggregate supply curve

The SRAS curve is horizontal:

The price level is fixed at a predetermined level, and firms sell as much as buyers demand.

P

P

SRAS

Y

Short-run effects of an increase in M

P

In the short run when prices are sticky,…

…causes output to rise.

P

Y

1

…an increase in aggregate demand…

Y

2

SRAS

AD

2

AD

1

Y

From the short run to the long run

Over time, prices gradually become “unstuck.”

When they do, will they rise or fall?

In the short-run equilibrium, if

Y Y

Y Y then over time, the price level will rise fall

Y Y remain constant

This adjustment of prices is what moves the economy to its long-run equilibrium.

The SR & LR effects of

M > 0

A = initial equilibrium

P LRAS

B = new shortrun eq’m after Fed increases M

C = long-run equilibrium

P

2

P

A

Y

C

B

Y

2

SRAS

AD

2

AD

1

Y

How shocking!!!

shocks : exogenous changes in aggregate supply or demand

Shocks temporarily push the economy away from full-employment.

An example of a demand shock: exogenous decrease in velocity

If the money supply is held constant, then a decrease in V means people will be using their money in fewer transactions, causing a decrease in demand for goods and services:

The effects of a negative demand shock

The shock shifts

AD left, causing output and employment to fall in the short run

Over time, prices fall and the economy moves down its demand curve toward fullemployment.

P

P

2

P

B

Y

2

LRAS

Y

A

C

SRAS

AD

2

AD

1

Y

Supply shocks

A supply shock alters production costs, affects the prices that firms charge.

(also called price shocks )

Examples of adverse supply shocks:

Bad weather reduces crop yields, pushing up food prices.

Workers unionize, negotiate wage increases.

New environmental regulations require firms to reduce emissions. Firms charge higher prices to help cover the costs of compliance.

( Favorable supply shocks lower costs and prices.)

CASE STUDY:

The 1970s oil shocks

Early 1970s: OPEC coordinates a reduction in the supply of oil.

Oil prices rose

11% in 1973

68% in 1974

16% in 1975

Such sharp oil price increases are supply shocks because they significantly impact production costs and prices.

CASE STUDY:

The 1970s oil shocks

The oil price shock shifts SRAS up, causing output and employment to fall.

P

2 In absence of further price shocks, prices will fall over time and economy moves back toward full employment.

P

1

P

B

Y

2

LRAS

Y

SRAS

2

AD

SRAS

1

Y

CASE STUDY:

The 1970s oil shocks

70%

Predicted effects of the oil price shock:

• inflation

• output

• unemployment

…and then a gradual recovery.

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

1973

12%

10%

8%

6%

1974 1975 1976

Change in oil prices (left scale)

Inflation rate-CPI (right scale)

Unemployment rate (right scale)

1977

4%

CASE STUDY:

The 1970s oil shocks

60%

Late 1970s:

As economy was recovering, oil prices shot up again, causing another huge supply shock!!!

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

1977

14%

12%

10%

8%

6%

1978 1979 1980

Change in oil prices (left scale)

Inflation rate-CPI (right scale)

Unemployment rate (right scale)

1981

4%

CASE STUDY:

The 1980s oil shocks

40%

1980s:

A favorable supply shock-a significant fall in oil prices.

As the model would predict, inflation and unemployment fell:

30%

20%

10%

0%

-10%

-20%

-30%

-40%

-50%

1982 1983 1984 1985 1986

Change in oil prices (left scale)

Inflation rate-CPI (right scale)

Unemployment rate (right scale)

10%

8%

6%

4%

2%

1987

0%

Stabilization policy

def: policy actions aimed at reducing the severity of short-run economic fluctuations.

Example: Using monetary policy to combat the effects of adverse supply shocks:

Stabilizing output with monetary policy

P

The adverse supply shock moves the economy to point B.

P

2

P

1

B

LRAS

A

SRAS

2

AD

1

SRAS

1

Y

Y

2

Y

Stabilizing output with monetary policy

But the Fed accommodates the shock by raising agg. demand.

results:

P is permanently higher, but Y remains at its fullemployment level.

P

2

P

1

P

B

Y

2

LRAS

Y

C

A

SRAS

2

AD

1

AD

2

Y

Chapter summary

1. Long run: prices are flexible, output and employment are always at their natural rates, and the classical theory applies.

Short run: prices are sticky, shocks can push output and employment away from their natural rates.

2. Aggregate demand and supply: a framework to analyze economic fluctuations

Chapter summary

3. The aggregate demand curve slopes downward.

4. The long-run aggregate supply curve is vertical, because output depends on technology and factor supplies, but not prices.

5. The short-run aggregate supply curve is horizontal, because prices are sticky at predetermined levels.

Chapter summary

6. Shocks to aggregate demand and supply cause fluctuations in GDP and employment in the short run.

7. The Fed can attempt to stabilize the economy with monetary policy.

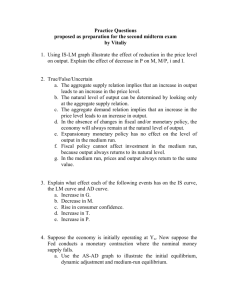

Estimates of fiscal policy multipliers

from the DRI macroeconometric model

Estimated value of

Y/ G

Estimated value of

Y/ T

Assumption about monetary policy

Fed holds money supply constant

Fed holds nominal interest rate constant

0.60

1.93

0.26

1.19

CASE STUDY:

The U.S. recession of 2001

During 2001,

– 2.1 million people lost their jobs, as unemployment rose from 3.9% to

5.8%.

– GDP growth slowed to 0.8%

(compared to 3.9% average annual growth during 1994-2000).

CASE STUDY:

The U.S. recession of 2001

Causes: 1) Stock market decline C

1500

1200

900

600

Standard & Poor’s

500

300

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003

CASE STUDY:

The U.S. recession of 2001

Causes: 2) 9/11

– increased uncertainty

–

– fall in consumer & business confidence result: lower spending, left

IS curve shifted

Causes: 3) Corporate accounting scandals

– Enron, WorldCom, etc .

– reduced stock prices, discouraged investment

CASE STUDY:

The U.S. recession of 2001

Fiscal policy response: shifted IS curve right

–

– tax cuts in 2001 and 2003 spending increases

• airline industry bailout

• NYC reconstruction

• Afghanistan war

CASE STUDY:

The U.S. recession of 2001

Monetary policy response: shifted LM curve right

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

Three-month

T-Bill Rate

What is the Fed’s policy instrument?

The news media commonly report the Fed’s policy changes as interest rate changes, as if the Fed has direct control over market interest rates.

In fact, the Fed targets the federal funds rate – the interest rate banks charge one another on overnight loans.

The Fed changes the money supply and shifts the LM curve to achieve its target.

Other short-term rates typically move with the federal funds rate.

What is the Fed’s policy instrument?

Why does the Fed target interest rates instead of the money supply?

1) They are easier to measure than the money supply.

2) The Fed might believe that more prevalent than IS

LM shocks are shocks. If so, then targeting the interest rate stabilizes income better than targeting the money supply.

(Problem Set #16.)

The Great Depression

240 30

220

200

Unemployment

(right scale) 25

20

180 15

160

140

Real GNP

(left scale)

120

1929 1931 1933 1935 1937 1939

10

5

0

THE SPENDING HYPOTHESIS:

Shocks to the IS curve

asserts that the Depression was largely due to an exogenous fall in the demand for goods & services – a leftward shift of the IS curve.

evidence: output and interest rates both fell, which is what a leftward IS shift would cause.

THE SPENDING HYPOTHESIS:

Reasons for the IS shift

Stock market crash exogenous C

–

–

Oct-Dec 1929: S&P 500 fell 17%

Oct 1929-Dec 1933: S&P 500 fell 71%

Drop in investment

– “correction” after overbuilding in the 1920s

– widespread bank failures made it harder to obtain financing for investment

Contractionary fiscal policy

– Politicians raised tax rates and cut spending to combat increasing deficits.

THE MONEY HYPOTHESIS:

A shock to the LM curve

asserts that the Depression was largely due to huge fall in the money supply.

evidence:

M 1 fell 25% during 1929-33.

But, two problems with this hypothesis:

–

–

P fell even more, so M / P actually rose slightly during 1929-31. nominal interest rates fell, which is the opposite of what a leftward LM shift would cause.

THE MONEY HYPOTHESIS AGAIN:

The effects of falling prices

asserts that the severity of the Depression was due to a huge deflation:

P fell 25% during 1929-33.

This deflation was probably caused by the fall in

M , so perhaps money played an important role after all.

In what ways does a deflation affect the economy?

THE MONEY HYPOTHESIS AGAIN:

The effects of falling prices

The destabilizing effects of expected deflation:

e

r for each value of i

I because I = I ( r )

planned expenditure & agg. demand

income & output

Why another Depression is unlikely

Policymakers (or their advisors) now know much more about macroeconomics:

– The Fed knows better than to let M fall so much, especially during a contraction.

– Fiscal policymakers know better than to raise taxes or cut spending during a contraction.

Federal deposit insurance makes widespread bank failures very unlikely.

Automatic stabilizers make fiscal policy expansionary during an economic downturn.