The Common Core and Argument Writing

advertisement

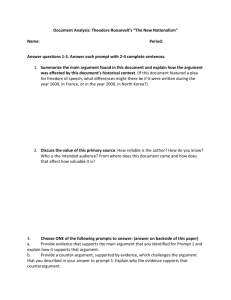

The Common Core and Argument Writing Write: What was your best writing experience? What was your worst writing experience? Common Core: Anchor Standards Text Types and Purposes* 1. Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence. 2. Write informative/explanatory texts to examine and convey complex ideas and information clearly and accurately through the effective selection, organization, and analysis of content. 3. Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using effective technique, well-chosen details, and well-structured event sequences. Production and Distribution of Writing 4. Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience. 5. Develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach. 6. Use technology, including the Internet, to produce and publish writing and to interact and collaborate with others. Research to Build and Present Knowledge 7. Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects based on focused questions, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation. 8. Gather relevant information from multiple print and digital sources, assess the credibility and accuracy of each source, and integrate the information while avoiding plagiarism. 9. Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research. Range of Writing 10. Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of tasks, purposes, and audiences. *These broad types of writing include many subgenres. See Appendix A for definitions of key writing types. Three Text Types 1. Argument 2. Informational/Explanatory 3. Narrative Grade-level Standards What assumptions do the standards pre-suppose? What do the standards imply? Consider order, wording, what is omitted, what is included. Persuasion vs. Argument Persuasion Argument • Ethos (author credibility) • Pathos (emotional appeals) • Logos (logical appeals) • Reason Persuasion vs. Argument "With its roots in orality, rhetoric has a bias for viewing audiences as particular. Aristotle said, ‘The persuasive is persuasive to someone.’ In contrast to rhetoric, writing has a bias for an abstract audience or generalized conception of audience. . . . For this reason, a particular audience can be persuaded, whereas the universal audience must be convinced; particular audiences can be approached by way of values, whereas the universal audience (which transcends partisan values) must be approached with facts, truths, and presumptions.” ~Miller & Charney Argument Common Core: What is Argument? To change reader’s point of view To bring about some action on the reader’s part To ask the reader to accept the writer’s explanation or evaluation of a concept, issue, or problem Is it argument or persuasion? Is it argument or persuasion? http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O9z71iNrlew Is it argument or persuasion? Is it argument or persuasion? Is it argument or persuasion? Is it argument or persuasion? Is it argument or persuasion? Grade-level samples Group by number and read associated sample. 1: Grade 12 (Freedom) 3:Grade 10 5: Grade 7 2: Grade 12 (Dress Codes) 4: Grade 9 6: Grade 6 (Pet Story) 7: Grade 6 (Dear Mr. Sandler) Discuss what the writing and annotations reveal about characteristics of argument writing (according to CCSS). Group by color and share your sample group’s findings. Generate a list of characteristics across samples: what are the qualities of argument writing, as revealed by these samples (in connection to standards)? Be prepared to share your group’s list. Elements of Argument Claim Evidence: relevant and verifiable Warrant: explanation of how the evidence supports the claim; often common sense rules, laws, scientific principles or research, and well-considered definitions. Backing: support for the warrant (often extended definitions) Qualifications and Counter-arguments: acknowledgement of differing claims Arguing Both Sides What can students learn? Arguments across disciplines “Although arguments in different fields use the same elements (claims, warrants, etc.), fields have different goals for argumentation, degrees of formality and precision, and modes of resolution, with the consequence that evaluative judgments should be made within fields, not between fields." Also. . . There are "multiple differences between academic argument and public argument." ~Miller & Charney Modes and Genres “Good writers know what kind of thing they are making with writing. They can answer the question, should someone ask, ‘what have I read in the world that is like what you are trying to write?’ No one I know would answer that question with words like narrative or persuasive or expository.These words simply aren’t operational for people who write. They aren’t the terms writers use to talk about or think about the writing they are producing. . . . Mode words don’t actually name the kinds of things people make with writing, so by themselves they don’t give anyone a vision for writing. Genre words do that work much better.” ~Katie Wood Ray Audience How do writers’ assumptions about audience affect production of a text? 1. How much to elaborate based on what they anticipate readers know 2. How much to tailor the development of claims 3. How much to care, since writers’ concerns are bigger when audience matters 4. How to accommodate audiences if writers don't identify with them “Considering the audience, therefore, is not simply a matter of selecting the information that readers need to understand the argument. Instead, writers must anticipate objections and questions and develop persuasive appeals, including building on common ground, refuting opposing claims, offering an acceptable reader-writer relationship, and presuming upon appropriate beliefs and values." ~Miller & Charney Building a Topic Bank School issues Local Issues State Issues National Issues Global Issues Choosing an arguable issue Arguments need. . . Arguments fail with. . . An issue No disagreement or An arguer reason to argue Risky or trivial issues Difficulty establishing common ground Standoffs or fights that result in negative outcomes An audience Common ground A forum Audience outcomes Narrowing a topic Preventing Bullying Name calling Texting bad names What about your class/grade? Genre PSA Topic Recycling in our school Topic Preventing bullying Common Core: What is Argument? To change reader’s point of view To bring about some action on the reader’s part To ask the reader to accept the writer’s explanation or evaluation of a concept, issue, or problem Mascots should be strong or tough and represent the area. They should be something people would be proud to be. Explanation A Miner would be a good mascot selection for our school. Evidence Claim Creating an argument Our area has mining as one of its primary industries, so the choice would represent our area. In addition, miners need to be tough because they do strenuous work—and dangerous work. They work hard to fill a need for people everywhere. That’s something to be proud of. Four corners The Supreme Court was right this week to reverse the ban on the sale of violent video games to children. Strongly Agree? Agree? Disagree? Strongly Disagree? Write for 3 minutes on your opinion. Go to corner of room matching your response. In your groups, you have several minutes to create an argument: claim, convincing evidence (yes, you can use your laptops), and explanation to present a two-minute argument to the rest of the groups. Point of View Annotation You will be reading this piece as one of the following people: Teenager Parent Police Officer Insurance Executive President of DriveCam Underline information that is important, surprising, puzzling or thought-provoking. For each time you underline information, jot a sentence or two about why you chose that bit to underline. The goal is to explain your role’s thoughts, opinions or questions. What is courage? “One day while Superman is flying around the skies of Chicago, he lands atop the Sears Tower. Using his supertelescopic vision, he sees a woman tied to a railroad track in the distant south. Squinting, he sees that it is Lois Lane. Beyond her, perhaps only fifty yards away, is a rushing freight train, which, in seconds, will cut her fragile body to pieces. Superman leaps from the Sears Tower and flies toward the train with the speed of light. He screeches to a halt on the tracks facing the train. The train smashes into his outstretched arms, and Superman stops it dead. He turns to Lois and asks, ‘Gee, are you all right?’” Defining Courage Write a full definition of the term: Include criteria Provide examples that meet and do not meet each criteria Avoid “when” after a linking verb Instead, use constructions like this: A courageous act is one. . . Courageous action involves the control of fear in the face of grave danger. For an act to be truly courageous, it must meet several criteria. First, because courage is considered to be a virtue, any courageous act must be a noble or virtuous act, such as saving a life or preventing harm to another person. Robbing a bank, no matter how dangerous and no matter how steadfast the actor, is not a noble or selfless act. Because it is not a virtuous act, it cannot be considered courageous. ~ Hillocks, 170 Locavore Movement A locavore is a person who has committed to eating locally grown or produced food. Read the materials you’ve been provided. Discuss the ideas in your groups. Create a v-chart of pros and cons of the movement V-chart as pre-write “To Locavore or Not?” A member of your city council agrees with the perspectives of the locavore movement. He has proposed encouraging the movement through a series of ordinances and financial incentives. Using what you know from the sources you’ve studied, write a statement expressing your position on the subject that will be read in front of the city council when it has hearings on the matter. Drawing as prewriting Read the article. Then sketch some of the key points from the article. Get into groups of three. Share your sketches: each person share the thinking behind the sketch. Groups make a poster that may integrate the ideas from the individual sketches or something that came up in discussion. All group members must contribute to the drawing of the poster. Gallery walk: In groups, use your post-its to comment or respond to the other posters. Comments should be about the ideas, not the drawing. Sign all names to your comment and move on when the time signal is given. As you move, also read the other comments and factor them into your comments. Scaffolding instruction Day 1: explore the genre. Read samples and analyze parts. Do fact/opinion work with essays. Day 2: Read and analyze more letters to the editor. Rank them in order of effectiveness. Begin list of criteria for this writing. Begin to generate possible topics. Day 3: Read and analyze some argument essays. Consider claims, evidence, organization, tone (snarl words and purr words). How do these apply to letters to editor? Homework: What do you want to write to editor about? Write your claim,why you hold the opinion and why someone might disagree with you. Day 4: Choosing newspaper and identifying audience. Look at more letters in your target newspaper. What topics? What language? How long? How organized? What do these things tell about the anticipated audience? Note to leave class: Which newspaper? Describe audience. Day 4: Inquiry—time in library for finding evidence. Homework, too? Scaffolding instruction Day 5: Fill in graphic organizer; evaluate quality of evidence. Take one piece of evidence and explain how it supports claim (teacher modeling). Turn in. Evidence Type of evidence Level of importance to audience Day 6: Logic and organization, transitions Day 7: Drafting, returning to models Day 8: Peer evaluation Day 9: Revision and further inquiry if necessary Day 10: Polishing; sentence combining and word choice Day 11: Due with addressed envelope Developing Curriculum Statements What do students need to know how to do? What understandings do they need to write this genre? Take one of the genres you developed at the end of yesterday and write some of the curriculum statements that might come from that genre. EX: Movie review for a website: Writer will state opinion of quality of movie. Writer will give short summary of movie. Writer will give evidence from movie (filming, story, actors’ credibility, etc.) to support claim. General qualities of effective writing Grouping ideas into sentences and paragraphs that carry meaning efficiently and move ideas forward Creating an effective thesis Introducing an idea effectively Connecting ideas (between sentences and paragraphs) Punctuating correctly Creating and maintaining an appropriate tone Concluding meaningfully Using words eloquently The structures and language of argument Incorporating others’ words or ideas Subordinating opposing views Organizing for greatest effect Maintaining an academic tone Analyzing and explaining data/sources adequately Recognizing the difference between reasons and evidence Evaluating quality of evidence/research Connecting ideas effectively Why? To establish clear relations between ideas “The best compositions establish a sense of momentum and direction by making explicit connections among their different parts, so that what is said in one sentence (or paragraph) not only sets up what is to come but is clearly informed by what has already been said. When you write a sentence, you create an expectation in the reader’s mind that the next sentence will in some way echo and be an extension of the first, even if—especially if—the second one takes your argument in a new direction.” ~Graff & Birkenstein Ways to make connections Transitions Pointing words Repetition of key words and phrases Synonyms Idea hooks Example “The only thing more dangerous than being on the back of a racehorse was being thrown from one. Some jockeys took two hundred or more falls in their careers. Some were shot into the air when horses would ‘prop,’ or plant their front hooves and slow abruptly. Others went down when their mounts would bolt, crashing into the rails or even the grandstand. A common accident was ‘clipping heels,’ in which trailing horses tripped over leading horses’ hind hooves, usually sending the trailing horse and rider into a somersault. Finally, horses could break down, racing’s euphemism for incurring leg injuries.” Seabiscuit, Hillenbrand Transitions EXAMPLES: Also, besides, furthermore, in addition, similarly, in other words, for example, for instance, although, but, despite the fact that, however, as a result, since, so, therefore, admittedly, as a result, consequently, yet Spot is a good dog. He has fleas. Spot is a good dog, even though he has fleas. Courage is resistance to fear. Courage is mastery of fear. Courage is not absence of fear. Pointing words EXAMPLES: this, these, that, those, their, such, her, it, etc. “Children wanted their kiddy-cars to go faster. First, the animal design was done away with. Then off went a couple of the wheels. The two remaining wheels were greatly enlarged and then aligned down the center of the vehicle. Finally, handlebars and footrests were added. These primitive two-wheelers went much faster than the four-wheeled kiddycars.” ~ Toys! Wulffson “Riders didn’t even have to leave the saddle to be badly hurt. Their hands and shins were smashed and their knee ligaments ripped when horses twisted beneath them or banged into the rails and walls. Their ankles were crushed when their feet became caught in the starter’s webbing.” ~ Seabiscuit, Hillenbrand Repetition of key words or phrases “She sighed as she realized she was tired. Not tired from work but tired of putting white people first. Tired of stepping off sidewalks to let white people pass, tired of eating at separate lunch counters and learning at separate schools. She was tired of ‘Colored’ entrances, ‘Colored drinking fountains, and ‘Colored taxis. She was tired of getting somewhere first and being waited on last. Tired of ‘separate,’ and definitely tired of ‘not equal.’” ~ Rosa, Giovanni Synonyms and pronouns “Candy is almost pure sugar. It is empty of nutritional value. It is an extravagance. It dissolves in water. It melts in your mouth, not in your hands. It’s the icing on the cake. Candy is so impossibly sweet and good that eating it should be the simplest thing in the world. So how can there be anything of substance to say about it?” ~ Candy and Me, Liftin “Religion was central to Egyptian life from the beginning, and the pharaoh played a key role in its rituals. In life, the ruler was thought to be the son of Ra, the all-powerful sun god.” ~ Secrets of the Sphinx, Giblin Idea hooks “Mark Twain is established in the minds of most Americans as a kindly humorist, a gentle and delightful ‘funny man.’ No doubt his photographs have helped promote this image. Everybody is familiar with the Twain face. He looks like every child’s ideal grandfather, a dear old white-thatched gentleman who embodies the very spirit of loving-kindness. Such a view of Twain would probably have been a source of high amusement to the author himself.” ~ Lively Art ofWriting, Payne In combination “Jebel Musa in the morning is like a tiger at dawn, a cat curled up in the shadows, its coat the color of pumpkin pie, its demeanor a misleading message: tame. As we arrived at the small plateau where climbers prep for the hike to come, the mountain seemed almost inert, waiting. At 7,455 feet, it’s not a particularly tall mountain: half as high as the tallest mountain in the Colorado Rockies; roughly as tall as the highest peak in the Appalachians. But it is impressive, completely dominating the landscape around it like a mother elephant dwarfing her babies. A mixture of red and gray granite fused together in an imposing, almost threatening mass, Mount Moses rises straight from the ground and softens slightly at the top like a drip castle. Though not as angular as Mount Ararat, nor as tall as nearby Mount Katarina, it still seems like a particularly imposing backdrop, waiting for some particularly majestic drama to take place in front of it.” ~ Walking the Bible, Feiler Using others’ ideas appropriately Quoting: using the exact words of another. Words must be placed in quotation marks and the author cited. Summarizing: putting the ideas of another in your own words and condensing them. Author must be identified. Paraphrasing: putting someone else’s ideas in your words but keeping approximately the same length as the original. Paraphrase must be original in both structure and wording, and accurate in representing author’s intent. It can not just be switching out synonyms in the original sentence. Author must be identified. Quoting Why use quotations? when the speaker’s name and reputation add credibility when the phrasing of the quotation is interesting or revealing and cannot be stated another way as effectively How effective are these examples? Many students “improve their reading ability” by looking at a text closely and by giving their first reactions to it (Burke 46). Mem Fox contests, “worksheets are the dead-end streets of literacy: there’s a non-message on each line, going nowhere, for no reason” (69). Hints: cut quotes to the core and use them like spice, sparingly Summarizing Summaries Should be shorter than original text Should include the main ideas of the original Should reflect the structure of the original text somewhat Should include important details Is this an effective summary of Source B? At the moment of harvest, food begins to lose vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals important for fighting disease and maintaining health. Because the decrease is negligible, however, even if food is days or weeks from harvest, it’s still possible to derive nutrition from it and be healthy by making smart food choices. Paraphrasing Source: “People of African descent in the Diaspora do not speak languages of Africa as their mother tongue.” Inappropriate Paraphrase: “People of African descent no longer speak the languages of Africa as their first language.” Appropriate Paraphrase: “Painter contends that cultural factors like language and religion divide African Americans from their ancestors. Black Americans speak a wide variety of languages, but usually these are not African.” Introducing others’ ideas Put source names either before the idea [Painter insists that the hula hoop can help fight diabetes] or after the idea in parentheses [Others find the idea ridiculous (Smith, Wilson)]. Use vivid and precise verb signals more than “says” or “believes” to show how an author feels or how an idea might relate to other ideas: agrees, recommends, insists, explains Make sure the idea adds to the point you are making. Dropping in unrelated quotes or names diminishes your credibility. SHOW how the idea contributes to YOUR argument. Practice Write a paragraph expressing your opinion about the locavore movement using either a quote, paraphrase, or summary statement from one of the sources. Be prepared to explain your choice: why you chose the option you did and how you incorporated it (either with appropriate punctuation and citation or by shortening or restating). Creating lessons Determine what students need to know how to do Find examples and models to show the skill Talk through the findings Give students chances to practice in low-risk situations Have them talk to each other about the practices Apply the new skill to writing currently being completed Decide on appropriate timing: when would be the best in the learning process? Writing Next 1. Writing strategies 2. Summarizing 3. Collaborative writing 4. Specific product goals 5. Word processing 6. Sentence combining 7. Prewriting 8. Inquiry activities 9. Process writing approach 10. Study of models 11. Writing for content learning And so. . . "Findings from this study suggest that teachers needn't teach to the test in a narrow, evaluation-focused manner; rather, they can develop tools that move students toward test-readiness while keeping writing process principles in focus.“ ~ Wolman-Bonilla Sources Caine, Karen. Writing to Persuade: Mini-lessons to Help Students Plan, Draft, and Revise. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2008. Daniels, Harvey “Smokey,” and Nancy Steineke. Texts and Lessons for Content-Area Reading. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2011. Dean, Deborah. StrategicWriting:TheWriting Process and Beyond in Secondary Schools. Urbana, IL: NCTE, 2006. ---. WhatWorks in Writing Instruction: Research and Practices. Urbana, IL: NCTE, 2010. Graff, Gerald, and Cathy Birkenstein. They Say, I Say:The Moves that Matter in Academic Writing. New York: Norton, 2006. Hillocks, George, Jr. Teaching ArgumentWriting. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2011. Miller, Carolyn R., and Davida Charney. “Persuasion, Audience, and Argument.” Handbook of Research onWriting. Ed. Charles Bazerman. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2008. 583-598. Smagorinsky, Peter, et al. The Dynamics of Writing Instruction: A Structured Process Approach for Middle and High School. Portsmouth, NH: 2010.