interactive notes (Murray)

advertisement

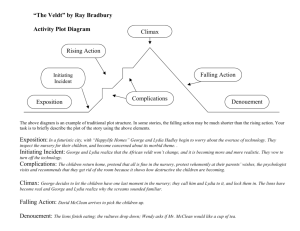

Interactive Notes Setting - - A futuristic world of comfort and leisure, but probably dated in the 1950’s. The fully-automated futuristic Happylife Home only cost $30,000 (l.14) so would be many decades ago at least. It is a world of apparently no work, only leisure and self-expressive activities. Lydia doesn’t even do typical housewife or childrearing activities ( l.103 & l. 115) and instead lets the automated house do everything (l. 133 the house cooks and serves food for them; l. 417-419 house shines shoes, massages, scrubs and washes, etc.). George just hangs around the house in his study drinking and smoking and taking sedatives to help him sleep (l.119-122) The Hadley’s live the American dream of a happy house, husband and wife with two children, but their activities are clearly futuristic. The children “televised home” (l.131) to say they’d be home late. The children get to their bedrooms by being sucked up a chimney flue and blown there (l. 238). The nursery brings fantasies to life at the thoughts of the occupants (l.141-2). Although most indications are that the setting is in the United States (currency is dollars, use of the word vacation rather than holiday, Santa Claus rather than Father Christmas), there is occasional word usage that suggests a more English background (the children wore jumpers, l. 200, the mention of “parlor” room l.83). Plot - - The Hadley’s seem to have an idyllic life in their happy home, but beneath the surface, or behind the perfect walls, is a lurking menace. The nursery in the house is a futuristic holodeck which brings thoughts to life. Although intended for relaxation and enjoyment, George and Lydia’s children have been getting carried away by entertaining dark fantasies. As George and Lydia share their doubts and wonder what action to take, their children return home from an outing. When confronted by their parents and threatened with the end of their spoiled lifestyle by “turning the house off” (l. 303), they feign ignorance and then set about the business of getting rid of the parents once and for all. The parents are lured into the nursery where fantasy becomes real and the childrens’ “death thoughts” (l.146) result in the parents being eaten by lions, with a similar fate awaiting the psychologist who visits to try and prevent anything bad happening. Conflict - The central conflict is between the parents and the children. The children control and manipulate the house toward their own ends, while the parents dither about how seriously to take the behaviours exhibited by their children. (Details of the conflict are developed in the sections pertaining to each character) Point of View - Limited omniscient point of view (or third person subjective). The narrator describes the story from the perspective of George Hadley. We see his thoughts and fears, and all the events and conversations in which he participates. This provides detailed knowledge of his thoughts and fears and helps build the sense of foreboding (mood) as George senses something is wrong but doesn’t trust his irrational thoughts or feelings. It also builds tension as the reader knows Lydia’s thoughts and feelings that she verbalizes in her conversations with George, but we know very little of the thought processes of the children and have to look for clues to their state of mind. Characters George - George is the central character of the story through whom the story is recounted. He is a husband, father and stereotypical 1950’s man. He’s analytical and leftbrain oriented, always trying to fix problems and looking for scientific evidence rather than feelings. When Lydia asks him to look at the nursery, he asks what’s wrong with it (l.2). When the lions in the nursery almost catch them (l.82-85), he logically explains why there’s nothing to worry about: “crystal walls, that’s all they are. . . . It’s all odorophonics and sonics.” He has “admiration for the mechanical genius” (l.59) who invented the nursery. When Lydia is afraid of the nursery, George dismisses her emotional femininity with a “Now Lydia…” and pats her (l.89-91). When the psychologist tells him the room feels bad, George responds “I want facts, not feelings.” (l.347) - Blinded by his logical mind, he is unable or unwilling to discern the danger he and Lydia are in. He “knew the principle of the room exactly” (l. 178) yet when it doesn’t respond and “the fool room’s out of order” (1. 184) he doesn’t believe Peter would have any idea how to work it if he doesn’t: “Peter doesn’t know machinery” (l. 194) He’s unsure of his feelings and isn’t very self-aware, as shows when he “tried to feel into himself to see what was really there” (l.123) when Lydia recounts his disconnectedness from the sedentary life he lives. Even after hearing the diagnosis from the psychologist that the room is dangerous and should be immediately shut down and dismantled, he doesn’t trust feelings and wonders “Is it that bad?” (l. 353) - Eventually, when faced with a preponderance of evidence, George begins to respond more on feelings but still doesn’t trust them. The same fears of the nursery possibly becoming real that Lydia had (l.88, l.126) become George’s fears that he confesses to the psychologist. (“I don’t suppose there’s any way . . . that they could become real?” l.388-90). Yet after turning off the nursery, he relents and lets the children back in the room after they cry incessantly (l.434439). Lydia - Lydia plays the role of the housewife in the futuristic story. Rather than the utilitarian focus of the 1950’s housewife, her automated house cleans itself, - - - cares for the children and even cooks the meals. Her life is one of leisure and sitting around thinking (l. 102-103). She feels that she can’t compete with a house that’s more efficient than her (l.114-16), and she struggles with her identity and sense of belonging as a result (l. 113) She is quite perceptive and trusts her feelings when they indicate that there’s something wrong with the idyllic life they lead. Lydia draws George’s attention to the changed nature of the nursery (l. 11) She is “particularly tense” (l. 50) with the prey that the lions are eating in the veldt, sensing something dark is happening. She ran for her life and was crying after the lions almost caught them (l. 76-78). She is the one who first realizes that the nursery has become “too real” (l. 88). Lydia has insight into George’s emotional state of mind even though he doesn’t. “You look as if you don’t know what to do with yourself in this house, either” (l. 119). She is the first to voice the possibility that “the children have thought about Africa and lions and killing so many days that the room’s in a rut: (l. 1889), and also accurately appraises Peter’s skill in controlling the room (l. 191-95). Lydia also realizes the sickening familiarity of the screams but doesn’t fully understand until it’s too late (. 285-7) She reverts back to stereotypical nurturing, mollycoddling housewife towards the conclusion when she takes the children’s side and asks George not to be so cruel (l. 412) in turning off the house. She loses her sense of foreboding and pressures George to give in to the children by saying “Oh George. . . it can’t hurt” (l. 433) to turn the nursery back on for a few minutes. The Children - Wendy and Peter are the spoiled, self-absorbed children of Lydia and George Hadley. They are presented like characters out of a fairy tale, with “cheeks like peppermint candy, eyes like bright blue agate marbles” (l.199). Even their names evoke characters out of a fairy tale or imaginary world (Peter Pan and Wendy in Neverland). They function as one character and one mind. They go everywhere together and share thoughts and ideas and schemes. The first three lines of dialogue with the children presents them as conjoined automatons (l.197ff); “Hello Mom. Hello Dad.” “We’re full of strawberry ice cream and hot dogs, but we’ll sit and watch.” Then looking blankly at each other when asked about the nursery and responding “Nursery?”(l.206) - They aren’t mentioned by name until almost a quarter of the way into the story, although the nursery where they spend lots of time is sufficiently dysfunctional to need a psychologist (“call a psychologist to look at it. . . It’s just that the nursery is different now than it was.” L. 5-11) They are described as “ten-yearold children” (l. 167) so possibly they could be twins, which would explain some of their conjoined state. They are old enough to have intelligent conversations yet present emotionally as children with capricious thoughts and responses. They have tantrums when disciplined (l.96) They silently collude to deceive their parents about the nature of the nursery by changing the program from Africa (l.212-225). - - From the beginning of the story, tension is present in the relationship between parents and children. In many ways the children act like the parents, “televising” home to say they’ll be late and to go ahead and have supper (l. 130-32). George reflects that the children had been having “Death thoughts. . . they were awfully young, Wendy and Peter, for death thoughts” (l.146). The parents know the children have neuroses about killing (l. 189 “the children have thought about Africa and lions and killing so many days the room’s in a rut”) George later has a moment of clarity when he observes “They come and go when they like; they treat us as if we were offspring.” (l.268). Various objects belonging to the parents are found inside the nursery and have obviously been mauled by the lions: George’s chewed wallet (l. 245-7), Lydia’s blood-stained scarf (l.399-401). When the nursery is temporarily turned off, Peter says “I hate you” (l. 426) and then “I wish you were dead” (l.428). The children are spoiled by their indulgent parents and also by the house that does everything for them. When faced with the prospect of the house being turned off and having to do everything for himself, Peter says that would be “horrid” (l. 309) and “I don’t want to do anything but look and listen and smell; what else is there to do?” (l. 312-13). All the children want to do is experience the nursery in their chosen environment of the veldt. When the nursery is about to be turned off, Peter appeals to the house for help. “ ‘Don’t let them do it!’ wailed Peter at the ceiling, as if he was talking to the house. “ (l. 424-25). And when they get their way and the nursery is turned back on, the children smile (l. 436, l. 481) as they know this is the time to take the ultimate step and lure their parents into the nursery to be killed. The house - The house (and the machinery/equipment contained in the house) is personified as being a living entity and becomes a surrogate parent for the children. The stove hums to itself while making supper (l. 9); the house is described in the language of a parent as it “clothed and fed and rocked them to sleep and played and sang and was good to them.” (l.14-15) The nursery is described as being conceived by a mechanical genius (l.59), a clever word-play intended to suggest both creation and design and also that the room is alive. - The house also supplants the real parents in the minds of the children. Lydia complains that the house is “wife and mother now, and nursemaid” (l. 113-4). David McClean states that “this room is their mother and father, far more important in their lives than their real parents” (l.370-1). The psychologist later observes that “nothing ever likes to die – even a room” (l. 398) and together with George he turns off the power and “killed the nursery” (l. 402). After George went around the house turning off appliances, the house “felt like a mechanical cemetery” (l. 421-22). The psychologist (David McLean) - David McClean enters the story when the conflict between children and parents is well-developed. He has immediate clarity in diagnosing the nursery and says “it certainly doesn’t feel good” (l. 346) and recommends that the nursery be torn - down immediately and the children brought to him for daily therapy sessions (l. 352). In conversation with George, he identifies that “the room has become a channel toward destructive thoughts” for the children (l. 357), and also identifies the root of the problem: “you’ve let this room and this house replace you and your wife in your children’s affections” (l. 369-70). He’s also aware of the hatred building inside the nursery (l. 372), has a sense of nervousness with the room similar to Lydia’s (l. 386) and identifies the paranoia so palpable “you can follow it like a spoor” (l. 318-19). For all his insight, the psychologist remains professionally detached and so doesn’t act in a way that bears out his recommendations. Despite his recognition of the danger posed by the room and the children’s murderous mindset, he blithely enters the room and joins the tea party with the children in the veldt, thus sealing his own fate (l. 478-488). Themes - - Reality vs illusion/fantasy. Thoughts becoming reality in the nursery – “the nursery caught the telepathic emanations of the children’s minds and created life to fill their every desire” (l. 141-2). The veldt was a “fantasy which was growing a bit too real” (l. 166) Africa in the nursery room felt “so real, so feverishly and startlingly real” (l. 65-66) Leisure and evil thoughts from idle minds? Take a vacation from the house, turn it off and experience real life (l. 103-4). T Death; children were having death thoughts (l.146-7), fascinated by watching lions kill. Turning off machines = death of the house, , children willing to contemplate murder of their physical family to keep their mechanical parent, the house, from being unplugged. Mood There is a sense of foreboding and menace throughout the story, despite the utopian setting. This is shown in the following ways: - Smells in the house that cleans itself. George had smelt the lions from his study, far from the nursery (l.170) The smell of lions pervaded the house even to the parents’ bedroom (l. 289) Heat: in the nursery, the heat from the African sun represents fear and nervousness. Screams echo through the house beyond the nursery where they originate, more faintly at first but just before the climax the screams from the nursery are loud enough to keep the parents awake in their bedroom.(l.279-89) Implied threats in the responses of the children to their parents. “I don’t think you’d better consider it anymore, Father.” (l. 317) Vultures circling, lions eating their prey, blazing heat and prickling perspiration Imagery - - - Strong repetition of imagery invoking the five senses, with a preponderance of sounds and smells. Initial description of the veldt (l. 36-42): “a wind of odor”, “hot straw smell of lion grass”, “cool green smell of the hidden water hole”, “rusty smell of animals”, “thump of distant antelope feet”, “papery rustling of vultures”. Five senses description of the lions (l. 65-71): “feel the prickling fur on your hand”, “the yellow of them was in your eyes like the yellow of an exquisite French tapestry”, “the sound of the matted lion lungs exhaling on the silent noontide”, “the smell of meat from the panting, dripping mouths”, “your mouth was stuffed with the dusty upholstery smell of their heated pelts”. Sounds and smells pervade the house: screams from the nursery heard in the bedroom are ominous, smell of the lions in George’s study or the parents’ bedroom, all indicate that the malevolent mood of the nursery is gradually overpowering the other areas of the house. Heat, danger and murder. Feeling the sun, “yellow hot Africa, this bake oven with murder in the heat” (l. 165). The word Africa itself becomes associated with danger and death, the summation of the murderous fantasies of the children that is evoked by the smells, sounds, colours and images of the veldt. The permanence of Africa in the minds of the children symbolizes their fixation on death. Style & Language - - - - There is important use of dialogue in the story. As the story is written from George’s perspective, he is in every scene and interacts with all the other characters. The reader only experiences the thoughts of other characters through dialogue. Passages of dialogue between parents and children are generally short, almost staccato sentences, increasing the pace of the story and heightening the tension. Similar dialogue between George and Lydia revolves around advances in their understanding or responding to some traumatic event (e.g. Lydia being afraid of how real the veldt is becoming l.87-94) The language is generally straightforward although some vocabulary might be difficult for junior high students. E.g. reproduced (l. 29), emanations (l. 141), forbade (l.270), eating with great relish (l. 340). There are some invented words, primarily to describe aspects of the futuristic house or lifestyle. E.g. “odorophonics” likely denotes an olfactory counterpart to a loudspeaker, “superreactionary” walls in the nursery, “televis[ing]” home instead of telephoning. Much of the vocabulary and imagery revolves around senses and experiencing reality – touch, smell, sound, feel. Colour is often involved as well – hot yellow sun and yellow lions, cool green grass, a red feast of meat for the lions. There are two fun references to other literary works: o Victor Appleton’s Tom Swift and His Electric Rifle (a youth-oriented adventure novel about Africa, published in 1911) l.210-11. The reference replaces rifle with Lion, making the lion the futuristic weapon instead of the laser-like electric rifle. o W. H. Hudson’s Green Mansions: a Romance of the Tropical Jungle (depicting Rima as the female Tarzan-figure and heroine in the 1904 novel set in South American jungle) l. 228-33. The appearance of Rima and her jungle in the story temporarily breaks the tension of the dangerous African veldt.